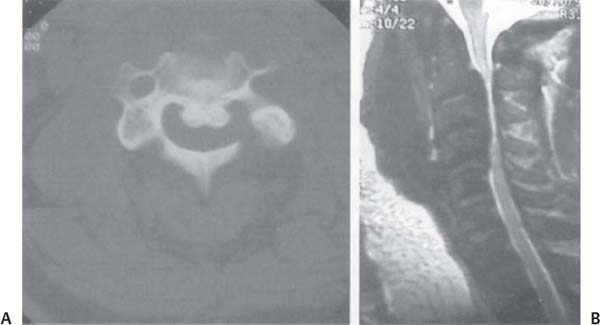

C H A P T E R 3 SPINAL DEGENERATIVE DISEASE I. CLERVICAL DISK DISEASE A. Signs/Symptoms 1. Radiculopathy—neck and interscapular pain, radicular arm pain, numbness and paresthesias, a sensory level and incontinence may be present, and lower motor neuron weakness; C8 and T1 radiculopathies may cause a partial Horner syndrome. 2. Myelopathy—upper motor neuron weakness, hyperreflexia, Hoffman’s, clonus, Babinski, a sensory level, and incontinence. B. Evaluation 1. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) 2. Nerve conduction study—occasionally useful to differentiate radiculopathy from neuropathy 3. Lhermitte sign—neck flexion causes caudal electrical shocks; often seen with multiple sclerosis and subacute combined system disease (SCSD); consider awake intubation if present 4. Spurling sign—pressing the vertex of the head with the head extended and tilted to the symptomatic side reproduces radicular pain C. Treatment 1. 90% of patients with acute cervical radiculopathy improve by 6 weeks with nonspecific conservative management Fig. 3.1 Lateral X-ray of C4–5, 5–6, and 6–7 cervical diskectomy and fusion. (With permission from Citow JS. Neurosurgery Oral Board Review. 1st ed. New York, NY: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2003: 144, Fig. 13.2.) 2. Useful medical therapy—oral steroids (Medrol dose pack), nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antispasmodics (for neck spasm), narcotics 3. Physical therapy for range of motion and traction exercises may be helpful. 4. Epidural steroids—not of clear benefit 5. Anterior cervical diskectomy and fusion—consider for patients who have significant weakness, long tract signs (bladder dysfunction), or debilitating pain, or who have failed conservative management 6. Posterior keyhole laminotomy with partial diskectomy for soft lateral disks—avoids the need for a fusion (consider with professional singers) 7. Plating—probably useful for two- and three-level procedures, though not proven for one-level fusions (Fig. 3.1) 8. Hard cervical collar—often used postop for 6 weeks II. CERVICAL SPONDYLITIC MYELOPATHY A. Signs/Symptoms—as above but more often myelopathy (usually when the canal is <12 mm and rarely when it is >16 mm) 1. Caused by direct neural compression, ischemia, and microtrauma 2. There may be a central cord syndrome. B. Evaluation 1. MRI and computed tomography (CT) (better bony detail). 2. Myelography—may be helpful, use Omnipaque 180 (lumbar) or 300 (cervical) 3. Avoid these medications if the patient is taking Metformin (also stop it 3 days preop). 4. Rule out—Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS; no sensory deficit, tongue fasciculations, distal fasciculations, or neck pain), multiple sclerosis, and SCSD C. Treatment 1. Anterior cervical diskectomy and removal of osteophytes around canal and foramen 2. Less often—full corpectomies 3. Posterior decompression if more than three levels are symptomatic or the pathology is mainly posterior 4. Add lateral mass fusion to posterior decompression if no lordoses. 5. Posterior decompression—precipitates swan-neck deformity in 30% of cases (try to avoid by leaving the soft tissue on the facets) and does not stop progression of osteophytes. 6. If both anterior and posterior approaches are needed, perform the anterior decompression and fusion first and follow with the posterior procedure in 8 weeks (consider supplemental fusion with lateral mass plates) 7. Success rate of surgery—improved 60%, unchanged 25%, worse 15% Fig. 3.2 Ossified posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL). (A) Axial computed tomgraphic bone window and (B) sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging demonstrate C2–5 PLL calcification with cord compression. (With permission from Citow JS. Neuropathology and Neuroradiology: A Review. New York, NY: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2001: 208, Fig. 292.) D. Ossified posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) 1. Treatment a. Decompress with anterior corpectomy followed by fusion b. Postsurgery—use a collar for 3 months c. Complication rate includes increased deficit 10%, failure to fuse 10%, and dural tear 25% (leave eggshell of floating bone on dura) d. CSF leaks—common and should be treated with fibrin glue and lumbar drainage (usually temporary) (Fig. 3.2A,B) III. UPPER CERVICAL SPINE DISEASES A. Ankylosing spondylitis 1. Most often occurs in young boys. 2. Associated with rheumatoid arthritis and HLA-B27 3. Many spinal levels may fuse, but it spares the occipitoatlas and atlantoaxial joints. 4. Joints may be unstable. 5. Frequent cause of lower back pain with sacroiliac erosion B. Down syndrome—patients often develop atlantoaxial dislocation and cervical stenosis. C. Morquio syndrome—patients often develop atlantoaxial subluxation by hypoplasia of the dens and ligamentous laxity. D. Rheumatoid arthritis 1. 80% of patients have cervical spine involvement. 2. Causes synovial proliferation with destruction of bone and ligaments 3. Atlantoaxial subluxation—occurs in 25% of patients a. Transverse ligament attachment becomes loose and symptoms are produced by a compressive pannus and instability (Fig. 3.3). b. Atlantodental interval (ADI) should be < 4 mm if the transverse ligament is not lax. c. Treatment—C1–2 fusion if ADI > 6 mm or patient is symptomatic (a Brook’s fusion with sublaminar wires and possible transarticular screws to add stability) d. Dislocation may need to be reduced before surgery, with up to 7 days of traction with 5–15 lbs e. Occiput–C2 fusion may be needed if C1 laminectomy is required for decompression or if the injury is unstable (there are frequent C1 arch fractures). f. May be necessary to perform a dens resection before or after stabilization g. Failure of fusion—up to 50% of cases h. Use a halo until the level is fused, around 12 weeks i. Before removing the halo ring, check a flexion–extension x-ray i. Operative mortality—15%, mainly due to cardiac and pulmonary issues 4. Basilar impression a. Degenerative condition with ventral compression of the spinal cord or lower brainstem by skull settling over the dens b. Signs/Symptoms—headache and cranial nerve dysfunction c. Treatment—reduction with 7–15 lbs followed by transoral odontoidectomy and then occiput–C2 fusion d. If reducible—usually no need for anterior decompression e. Basilar invagination—congenital condition with a fusion of C1 to the occiput i. Not reducible with traction, but occasionally requires decompression f. Treatment—transoral odontoidectomy i. Performed supine with head in neutral position ii. Place the Crockard retractor to move tongue caudally, soft palate rostrally, and endotracheal tube laterally iii. Clean mouth with Betadine iv. Palpate anterior tubercle of C1, inject posterior pharyngeal wall with lidocaine and epinephrine, and make longitudinal incision from above arch to base of C2 v. Retract pharyngeal tissue as one layer after subperiosteal dissection with Bovie vi. Remove anterior arch of C1 and dens with a drill and pituitary forceps vii. Underlying soft tissue pannus may be carefully dissected off dura, but be careful to avoid a dural tear viii. Close incision in one layer ix. Most patients will require a fusion. Fig. 3.3 Sagittal T1-weighted magnetic resonance image with a large pannus posterior to the dens. (With permission from Citow JS. Neurosurgery Oral Board Review. 1st ed. New York, NY: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2003: 149, Fig. 13.4.) IV. THORACIC DISK DISEASE A. Posterolateral transpedicular approach—may be adequate exposure for some thoracic disks, but central disk removal is performed blindly with angled instruments (Woodson elevator) 1. Remove hemilamina above and below disk space as well as the facet joint. 2. Drill off pedicle from level below and clear out lateral and inferior disk space 3. Use Woodson elevator to push disk material down into the created trough B. Costotransversectomy—allows direct line of vision to extend more medially 1. Initiate dissection as above; then remove transverse process and 4 cm of proximal adjacent rib 2. Complications—pneumothorax and radicular artery injury C. Lateral extracavitary approach—allows better view of midline, but not as good as transthoracic approach D. Transthoracic approach—best view for anterior pathology such as disk disease, burst fractures, or tumors 1. Upper T-spine—use transsternal approach 2. Middle T-spine—use right thoracotomy (avoid the heart) 3. Lower T-spine—use left thoracotomy (Fig. 3.4) 4. Thoracolumbar junction—use left retroperitoneal approach (avoid the liver) 5. Complications—radicular artery injury, pulmonary injury, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-pleura fistula 6. Thoracoscopic approaches are gaining in popularity. V. LUMBAR DISK DISEASE A. Signs/Symptoms—lower back and radicular leg pain, numbness, paresthesias, lower motor neuron weakness, and rarely incontinence 1. Cauda equina syndrome—saddle anesthesia and bladder and bowel incontinence or retention, usually due to a massive L5–S1 disk herniation B. Evaluation 1. Straight leg raise (Lasegue sign)—performed supine with leg straight to test lower lumbar roots (L5–S1) 2. Reverse straight leg raise—performed prone with flexed knees to test upper lumbar roots (L2–4) 3. MRI—most useful test Fig. 3.4 Transthoracic approach. (With permission from Citow JS. Neurosurgery Oral Board Review. 1st ed. New York, NY: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2003: 151, Fig. 13.6.) 4. CT-myelography—reserved for more subtle pathology 5. Nerve conduction velocity (NCV) test—needed (though rarely) to distinguish radiculopathy from neuropathy C. Treatment 1. 90% of patients with acute lumbar radiculopathy improve by 6 weeks with nonspecific conservative management. 2. Useful medical therapy—same as for cervical disk disease 3. Physical therapy—to strengthen abdominal and back muscles will help prevent future back problems 4. Lumbar epidural steroid injections—may be helpful 5. Indications for early surgery—significant weakness, bowel or bladder dysfunction, or debilitating pain not controlled by narcotics 6. Gold standard procedure—microdiskectomy 7. For an extraforaminal (lateral) lumbar disk, there are two standard approaches. a. Hemilaminotomy to identify the nerve root followed by a complete facetectomy until the disk is identified (consider fusion if taking entire facet) b. Extrafacet approach with dissection over the lateral facets and transverse processes to find the nerve root and disk under the intertransverse ligament c. Iliac crest may need to be drilled down to reach the extruded disk D. Complications 1. Infection 5% 2. Disk reherniation 5% 3. Increased deficit 1–5% 4. Dural tear 10% (20% on reoperations) 5. Positioning pressure sore 6. Arachnoiditis—central adhesive nerve root cords or roots adherent to the dura seen on MRI 7. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) 8. Pulmonary embolism 9. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy 1%—occurs 4 days to 20 weeks after surgery and treated with physical therapy, steroids, and sympathetic blocks 10. Vessel injury (rarely)—aorta and vena cava bifurcate into iliac vessels at L4 11. Superficial infection—treat with antibiotics 12. Deep infection—usually requires debridement with closure over a drain a. Evaluate the infection with complete blood count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), cultures, and contrasted MR. A. Signs/Symptoms 1. Similar to lumbar disk disease symptoms but usually with a more insidious onset 2. Typically, neurogenic claudication with leg pain and weakness exacerbated by ambulation and relieved over minutes by sitting, lying down, or leaning forward on a grocery cart a. This may be confused with vascular claudication that improves immediately with rest and is evaluated with lower extremity arterial Doppler studies and an ankle/brachial blood pressure < 0.6. 3. Thigh pain—can be caused by trochanteric bursitis or hip arthritis, but the pain should not extend past the knee and there should be no sensory loss 4. Lateral recess syndrome—compression of the nerve root adjacent to the pedicle by an enlarged superior facet process (< 4 mm of AP space) B. Evaluation—MRI and CT myelography if needed C. Treatment 1. Conservative management as with disk disease, though some will eventually require laminectomy with medial facetectomies, foraminotomies, and lateral recess decompression 2. Try to leave as much of the facet as possible because 1–5% of patients become unstable after lumbar decompression 3. Vertically aligned facets—more likely to become unstable 4. Fusion—not needed if 50% of facet is left intact and disk is untouched 5. Lumbar fusion—best performed with pedicle screws augmenting a bony lateral fusion over decorticated transverse processes 6. Posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF) cages—may be placed to augment a posterior fusion with a tall disk space, but have not been proven to be an effective stand-alone device (this is an area of controversy) 7. Open or laparoscopic anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF) cages also may be used in place of a PLIF. ALIF is typically reserved for discogenic back pain confirmed by discogram. 8. Incision for ALIF placement is at the lateral edge of the rectus abdominis with a retroperitoneal dissection and great vessel mobilization. 9. Pedicle screws—usually 5.5 or 6.5 mm in diameter and 40–55 mm in length a. Should be aimed 20 degrees medial at L5, 30 degrees medial at S1, and sink 80% into the body (as guided by fluoroscopy or an image-guided system) (see the Lumbar Trauma section for more information.) 10. 80% of patients are improved with surgery. D. Complications—same as lumbar disk disease complications 1. 10–20% of postfusion patients develop adjacent stenosis over 10 years. VII. SPONDYLOLISTHESIS—Subluxation, May Have a Pars Defect A. Spondylolysis refers to the defect without subluxation. B. Spondylolisthesis varieties 1. Isthmic—little degenerative changes, possibly traumatic, usually at L5–S1 2. Dysplastic 3. Degenerative—90% at L4–5 and most others at L3–4 4. Traumatic 5. Pathologic D. Treatment—as with lumbar stenosis with the addition of pedicle screws (though some reports suggest fusion not needed because most cases of degenerative spondylolisthesis do not slip more after decompression) (Fig. 2.11A,B) E. Symptomatic spondylolysis (back pain) 1. Evaluation—dynamic studies and local injections into the pars (to determine if this is indeed the pain source) 2. Treatment—consider repairing the pars directly with a screw (avoiding a fusion) or performing the traditional fusion (most common treatment) VIII. FACET-MEDIATED BACK PAIN (TYPICALLY FACET ARTHROPATHY) A. Signs/Symptoms—pain is mainly in the paraspinal lower back but can be referred to upper thigh in nonradicular pattern B. Evaluation—MRI (rule out tumor or infection) and dynamic x-ray (rule out instability) and may be tender to palpation over facets C. Treatment—physical therapy and NSAIDs 1. Refractory cases may be treated with radiofrequency facet denervation, facet injections, or fusion. IX. COCCYDYNIA A. Signs/Symptoms—local tenderness over the coccyx B. Evaluation—MRI C. Treatment—NSAIDs, doughnut cushion, injections, and possibly resection (low success rates) X. MYELOPATHY DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS (See Neurology Section) A. Spinal cord compression—disk, bone, tumor, abscess B. Spinal cord tumor C. ALS—tongue fasciculations, normal sensation D. Transverse myelitis E. Spinal cord cerebrovascular accident (CVA)—aortic dissection F. Syphilis—tabes dorsalis G. Subacute combined system disease (SCSD) XI. FEMORAL NEUROPATHY—the femoral nerve arises from L2, 3, and 4 to supply sensation to the anterior thigh and innervate the iliopsoas and quadriceps muscles. A. Thigh adductors—not weak with a femoral neuropathy; they are innervated by the obturator nerve (L2,3) B. L4 radiculopathy should have sensory loss from knee to medial malleolus (not anterior thigh), normal iliopsoas strength, and weakness of quadriceps, ankle dorsiflexion, and thigh adductors. XII. FOOT DROP—Usually from an L4 or 5 radiculopathy (painful) or a common peroneal nerve palsy (painless, normal gluteus medius strength with internal rotation of flexed hip and normal foot inversion); parasagittal meningioma may also present with footdrop A. Superficial peroneal nerve (L4,5)—foot eversion and sensation to the dorsum of the foot B. Deep peroneal nerve (L4,5)—dorsiflexion and a small area of sensation at the big toe web space C. Tibial nerve (L5,S1)—foot inversion and plantar flexion with sensation to the sole of the foot D. L5 proximal branches—gluteus medius (L4,5) for internal thigh rotation and gluteus maximus (L5–S1) to resist straight leg raise (SLR) E. Sciatic nerve injury proximal to the peroneal division produces flail foot (no plantar- or dorsiflexion)

3: SPINAL DEGENERATIVE DISEASE

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree