CHAPTER 33 OCD and OCD-Related Disorders

OVERVIEW

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a common disorder that affects individuals throughout the life span. This disorder has been listed as one of the ten most disabling illnesses by the World Health Organization.1 The National Comorbidity Survey Replication indicated that OCD is the anxiety disorder with the highest percentage (50.6%) of serious cases.2 Putative OCD-related disorders (OCRDs) include somatoform disorders (e.g., body dysmorphic disorder [BDD] and hypochondriasis), tic disorders (e.g., Tourette’s disorder), and impulse control disorders (e.g., trichotillomania [TTM] [Figure 33-1] and pathological skin picking).

Approximately 2% to 3% of the world’s population will suffer from OCD at some point in their lives,3 and higher numbers will suffer from OCRDs. Most individuals with OCD spend an average of 17 years before they receive an appropriate diagnosis and treatment for their illness.4 Although these disorders have a waxing and waning course, they frequently increase in severity when left untreated, which causes unnecessary pain to those afflicted and to their families. Hence, an understanding of OCD and OCRDs by clinicians is imperative to reduce the gap between the onset of symptoms and the eventual diagnosis, and to promote implementation of appropriate strategies for long-term symptomatic relief. This chapter provides a general description of these conditions, followed by characterization of the epidemiology (including risk factors), the genetics, and the clinical features for OCD and OCRDs. Strategies for the clinical evaluation (including use of laboratory tests) and treatment of the illnesses are then discussed.

DEFINITIONS

OCD is listed as an anxiety disorder by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—Fourth Edition (DSM-IV).3 It is characterized by repetitive thoughts, images, impulses, or actions that are distressing, that are time-consuming, or that affect function. The condition is often kept a secret because of the shame associated with its peculiar symptoms. Symptoms experienced by OCD sufferers are diverse. Obsessions can focus on aggressive or sexually intrusive thoughts, religious scrupulosity, concerns about symmetry, hoarding, pathological doubt, or thoughts of contamination. Compulsions are also varied; they include washing, counting, checking, repeating, hoarding, ordering, and the conduct of mental rituals. More often than not, patients with OCD experience more than one type of symptom at any given time, and the symptoms change over the course of the illness.

OCRDs are characterized by the presence of repetitive or excessively compulsive behaviors, some of which are preceded by increased tension and followed by a sense of relief. What constitutes an “OCD spectrum” or “OCD-related” disorder remains controversial. At present, prominent researchers cannot agree on how broad the OCD spectrum should be.5 Thus, OCRDs discussed in this chapter are those that are most often considered in this category.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS

Prevalence

Symptoms of OCD are common. Approximately 50% of the general population engage in some ritualized behaviors,6 and up to 80% experience intrusive, unpleasant, or unwanted thoughts.7 However, for most individuals these behaviors do not cause excessive distress, occupy significant amounts of time, or impair function; thus, they do not represent OCD. Regarding a clinical diagnosis of OCD in adults, the 1-month prevalence rate is 0.6%,8 and the reported 12-month prevalence ranges from 0.6% to 1.0% for DSM-IV–defined OCD9,10 and from 0.8% to 2.3% for DSM-III-R–defined OCD.11

Measured lifetime prevalence rates for OCD appear to depend on the version of the DSM used to determine diagnoses. The estimated lifetime prevalence is 1.6% using the DSM-IV.2 Using the DSM-III, the lifetime rate was 2.5% in the U.S. Epidemiologic Catchment Area Survey,11 and the prevalence ranged between 0.7% (in Taiwan) and 2.5% (in Puerto Rico and in seven other countries surveyed).12 These differences may be due to the fact that the DSM-IV better defines obsessions and compulsions and requires significant clinical distress or impairment to confirm a diagnosis.9

The prevalence rates of the OCRDs vary. Many of these disorders co-occur with each other and with OCD. Regarding somatoform disorders, the estimated prevalence rate of hypochondriasis is 1% to 5% in the general population and 2% to 7% among primary care outpatients. Unfortunately, the prevalence rate of BDD is difficult to estimate accurately (given the secrecy of the disorder), but estimates range from 0.7% to 2.3% in the general population, and from 6% to 15% in cosmetic surgery settings.13 For the other OCRDs, the prevalence of Tourette’s disorder is 0.1%. The exact lifetime prevalence of TTM is unknown, but rates from 1% to 2% have been reported for cases that satisfy the full diagnostic criteria.14 The prevalence is even higher for subclinical hair-pulling, regardless of preceding tension and subsequent gratification.14–17 In patients with OCD, the prevalence of co-morbid broadly defined OCRDs exceeds that for the general population, with reported rates of over 55%.18

Age of Onset

There appears to be a bimodal age of onset for OCD. Approximately one-third to one-half of adults with OCD developed the disorder in childhood.12,19 The National Comorbidity Survey Replication reported that the median age of onset was 19 years; 21% of cases emerged by age 10.10 The mean onset for OCD in adults occurs between 22 and 35 years of age.20 Some studies report another incidence peak in middle to late adulthood,21 but others report that onset of OCD after age 50 is relatively unusual.22

The age of onset for individuals with OCD appears to be an important clinical variable. Early-onset OCD may have a unique etiology and outcome, and it may represent a developmental subtype of the disorder.23,24 Childhood-onset OCD is also associated with greater severity23,25 and with higher rates of compulsions without obsessions.23,24 An earlier age of onset was associated with higher persistence rates in a meta-analysis of long-term outcomes for childhood-onset OCD.26 Co-morbid rates of tic disorders,27 attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and anxiety disorders28 are also higher than in adult-onset OCD.

For the somatoform-based OCRDs, hypochondriasis is thought to develop most frequently in early adulthood,29 whereas BDD tends to present during adolescence preceding adulthood. Many individuals with BDD have had life-long sensitivities regarding their appearance. Tic disorders are much more common in children and adolescents than they are in adults, because these disorders with an age of onset in childhood and tend to remit over time. The average age of onset of Tourette’s disorder symptoms is approximately 7 years, ranging from 3 to 8 years.30 The age of onset for TTM in adults is approximately 13 years.31 However, among children with chronic hair-pulling, the average age of onset is reported to be as low as 18 months.32

Gender

The gender profile of OCD differs between age-groups and populations. In clinical samples of those with early-onset OCD, this disorder appears to be more common in males.24,25,33 However, epidemiological studies of children and adolescents report equal rates in boys and girls.34,35 In contrast, a slight female predominance is reported in epidemiological studies for adults.12,19,21,36

There is no clear gender predominance across the OCRDs. Men and women are equally affected by both hypochondriasis37 and BDD.13 Whereas tics are four times more common in men than women,38 in contrast TTM is more common in females. However, the younger the sample is for TTM, the more even is the gender distribution.39

Race and Cultural Factors

The prevalence for OCD tends to be fairly consistent across countries, which suggests that race and culture are not central causal factors for OCD. However, these factors may influence the content of obsessions and compulsions. The disorder is evenly distributed across socioeconomic strata in most studies, although there tends to be a paucity of minority subjects in epidemiological and clinical studies in the United States.11

Risk Factors

There are no clearly established environmental risk factors for OCD. However, some patients describe the onset of symptoms after a biologically or emotionally stressful event (such as a pregnancy or the death of a loved one). Streptococcal infection may be associated with an abrupt, exacerbating-remitting early-onset form of OCD, which is termed pediatric autoimmune disorders associated with streptococcus (PANDAS).40–42

Little is known regarding the etiology of BDD, although genetic predisposition, serotonin system deficits, and family biases (e.g., that appearance is prized) and specific events (such as teasing) may play a role. Exacerbating factors include brightly lit rooms, locations with mirrors or reflective surfaces, and social situations with many people.13 Hypochondriasis is likely to arise during periods of increased stress, following the diagnosis of illness or the death of a loved one, and following media exposure to illness-related stories.43

For Tourette’s disorder, perinatal events30 and abnormal immune responses to infectious agents (such as streptococcus)44 are considered to be risk factors, although the latter is somewhat controversial.45 Regarding TTM, certain factors (such as cognitions, negative affective states, and particular settings) are known to trigger hair-pulling episodes, although these are not necessarily risk factors. A clear understanding of the pathogenesis of TTM remains limited.46

CLINICALLY RELEVANT GENETICS

Numerous lines of evidence support the genetic basis for OCD and OCRDs. Twin and family aggregation studies of OCD report higher than expected rates of OCD in relatives.47–50 This was confirmed in a meta-analysis of five OCD family studies that included 1,209 first-degree relatives,51 which calculated a significantly increased risk of OCD among relatives of probands (8.2%) versus controls (2.0%) (odds ratio [OR] = 4.0). However, in studies ascertained through children or adolescents, familial risk appears to be even higher (9.5% to 17%) than that for those with later-onset OCD.52–58 In family studies by Nestadt, Pauls, and others, approx-imately half of the OCD cases have not proven to be familial.59–61

Although twin studies can provide compelling evidence for the role of genetic factors in complex neuropsychiatric disorders, no large systematic twin studies have focused exclusively on OCD. Further, twin studies cannot provide conclusive evidence that unique genes are important for the manifestation of OCD. A recent review of OCD twin studies dating back to 1929 concluded that obsessive-compulsive symptoms are heritable, with genetic influences ranging from 45% to 65% in children and from 27% to 47% in adults.62

Molecular genetic studies have begun to provide evidence that specific genes play a role in the manifestation of OCD. Segregation analyses have examined familial patterns of OCD transmission and noted the best fit for a dominant model in some studies.61,63,64 However, results of combined segregation analyses suggest that OCD’s familial transmission is difficult to model. The most parsimonious solution suggests that there are at least some genes of major effect65; it is highly likely that OCD is an oligogenic disorder with several genes that are important for the expression of the syndrome. At the present time, none of the four linkage studies for OCD or OCD symptoms reported genome-wide significance.66–68 The following regions have been suggestive for susceptibility loci: 1q, 6q, 9p, 19q, 7p, and 15q.

OCD candidate genes have been studied based on their function and also their position in the genome. Serotonin-related genes considered in OCD include those coding for the serotonin transporter (5-HTT)69–71 and receptors (5-HT2A,72 5-HT2B,73 5-HT2C,74 and 5-HT1B),70 as well as the serotonin enzyme (tryptophan hydroxylase).75 Dopamine (DA)–related genes studied in OCD include DA transporter genes76,77; D2, D3, and D4 receptors78; COMT79; and MAO-A enzymes.80,81 Glutamate-related genes reported to be associated with OCD include GRIK,82,83 GRIN2B,83,84 and the glutamate transporter (SLC1A1).85–87 Other genes that have been reported to be associated with OCD include the white-matter genes OLIG288 and MOG.89 Given the complexity of the OCD phenotype, it is unlikely that a single candidate gene will have a major impact on the disorder, and few if any genes have been consistently replicated in large samples.

With respect to genetic studies of OCRDs, Bienvenu and colleagues90 explored familiality of these illnesses among the relatives of OCD probands and found significantly higher than expected rates of BDD (OR = 5.4), somatoform disorders (OR = 3.9), grooming disorders (OR = 1.8), and all spectrum disorders combined (OR = 2.7). Relatives of OCD probands have elevated rates of Tourette’s disorder and chronic tics (4.6%) versus relatives of controls (1%), regardless of a diagnosis of Tourette’s disorder in the probands.49,91 This is especially true in families with earlier-onset OCD. Moreover, relatives of Tourette’s disorder probands have elevated rates of OCD as compared with controls.92,93 It has also been suggested that TTM has an underlying genetic basis.46,94,95 In the only twin study exploring the genetic basis for TTM, a significantly greater concordance rate was present among monozygotic (31.9%) than dizygotic (0%) twins for “clinically significant hair-pulling.”96

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The pathophysiology of OCD is incompletely understood, although neurobiological models implicate dysfunction in several corticostriatal pathways.97,98 OCD is considered to be a neuropsychiatric disorder, in part as it is associated with neurological conditions and movement disorders. In fact, OCD may develop following birth injury,99 temporal lobe epilepsy,100 or head injury.101

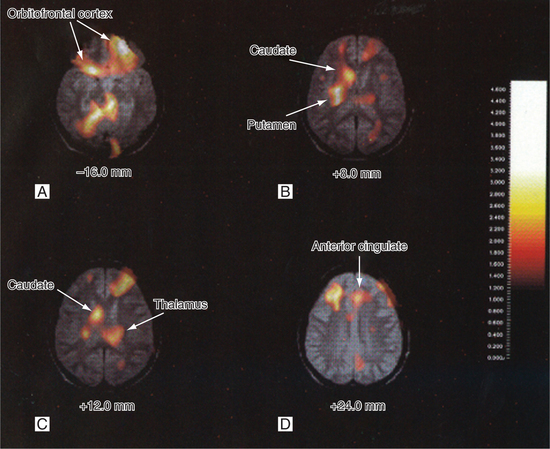

Neuroimaging findings indicate that OCD involves subtle structural and functional abnormalities of the orbitofrontal cortex, the anterior cingulate cortex, the caudate, the amygdala, and the thalamus (Figure 33-2).97,98,102–104 The nodes of the implicated frontocortical-basal ganglia-thalamocortical circuit are interconnected via two principal white-matter tracts—the cingulum bundle and the anterior limb of the internal capsule.

The basal ganglia are likely associated with abnormal compulsions of OCD. Damage to this region in both humans105 and animal models106 results in behaviors that resemble compulsions. Furthermore, diseases in humans that result from deterioration of basal ganglia (such as Huntington’s chorea and Parkinson’s disease) have increased rates of OCD.107,108 Prefrontal and orbitofrontal regions are responsible for filtering information received by the brain and for suppressing unnecessary responses to external stimuli; these may be more associated with the obsessive symptoms of OCD.

There is also evidence of brain white-matter involvement in OCD. Patients with OCD have significantly more gray matter, less white matter, and abnormalities of white matter than do normal controls, which suggests a possible developmental etiological process.109–111 Neurochemically, serotonergic112 and glutamatergic systems have been implicated in OCD.

Other medical pathophysiological factors may be involved in the etiology of OCD. In rare cases, a brain insult (such as encephalitis, a striatal lesion [congenital or acquired], or head injury) directly precedes the development of OCD.112 Research suggests that autoimmune processes, precipitated in some childhood-onset cases by beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection, may cause damage to striatal neurons in childhood-onset cases of OCD.113–115

CLINICAL FEATURES AND DIAGNOSIS

The DSM-IV3 is currently used for the diagnosis of OCD and OCRDs (Table 33-1). The diagnosis of OCD requires the presence of either obsessions or compulsions. These must be significantly distressing, time-consuming, or interfering with the person’s normal routine, occupational function, social activities, or relationships with others. Figure 33-3 illustrates the living quarters of a patient with OCD and hoarding behavior.

Table 33-1 Diagnostic Criteria for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (DSM-IV)

DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—Fourth Edition.3

Figure 33-3 Cluttered and overcrowded home of an OCD patient suffering with hoarding obsessions and compulsions.

Revisions from the DSM-III-R to the DSM-IV for OCD include the addition of mental compulsions, and exclusion, if the content of the obsessions or compulsions is restricted to another Axis I disorder (e.g., concern with appearance in the presence of BDD, or repeated hair-pulling with TTM) or if the obsessions or compulsions are due to the direct effects of a substance or general medical condition. A “poor insight type” may be specified if the person does not recognize the excessive or unreasonable nature of the obsessions and compulsions most of the time during the current episode. Figure 33-4 provides an image of a classic OCD symptom, handwashing.

It has been proposed that clinical features of the OCRDs may be categorized into three symptom clusters.116 These are a “somatic” cluster for BDD and hypochondriasis; a “reward deficiency” cluster for TTM and other impulse control disorders (such as Tourette’s disorder); and an “impulsivity” cluster for compulsive shopping, kleptomania, and intermittent explosive disorder. However, as previously noted, whether all of these disorders (especially the latter cluster) constitute OCRDs is an issue of ongoing debate.5

BDD is a disorder in which individuals suffer from a preoccupation with a slight or imagined defect in appearance that causes significant distress or impairment that is not strictly a manifestation of another disorder. Hypochondriasis involves a preoccupation with the inaccurate belief that one has, or is in danger of developing, a serious illness. This fear persists despite extensive evaluation and subsequent reassurance of good health by a medical professional. Tourette’s disorder is characterized by the presence of chronic motor and vocal tics, with symptoms manifesting before 18 years of age. These symptoms should persist for at least a year, with no 3-month symptom-free intervals.3 TTM involves repetitive hair-pulling that results in significant hair loss that is preceded by increasing tension, followed by relief or pleasure, and results in impaired function or significant distress.117,118

EVALUATION, TESTS, AND LABORATORY FINDINGS

Regarding the history of present illness, the duration and severity of symptoms and their precipitating, exacerbating, and ameliorating factors should be elucidated. Functional consequences of these symptoms in home, work, and social environments and the level of insight, resistance, and control over symptoms should also be assessed. Family insight and accommodation of symptoms (which permits their perpetuation) are other important factors to be determined. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) and checklist should be used to record the severity and lifetime presence of specific symptoms. There is also a children’s version of this scale, the Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS). Alternatively, the Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory119 or the Obsessive-Compulsive Checklist120 may be used.

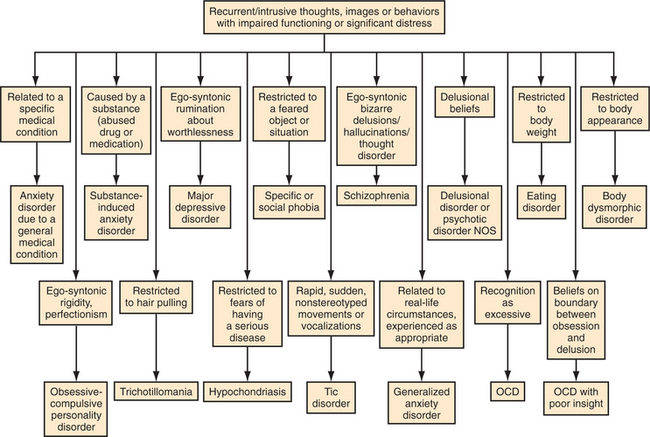

Following the initial assessment, co-morbid illnesses or other more responsible disorders should be ruled out. (Figure 33-5 shows an algorithm for creation of a differential diagnosis.) For individuals with OCD, co-morbid OCRDs should be assessed, and vice versa. Tics and eating disorders121 may be more common in individuals with OCD. Clinical measures used to record OCRDs include the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) for tics and Tourette’s disorder, the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Hairpulling Scale for TTM,122 and the Body Dysmorphic Disorder Questionnaire for BDD.123 Other conditions that should be assessed include depression and the risk of suicide. Other co-morbidities that occur at higher than expected rates include bipolar disorder,124 personality disorders, and anxiety disorders (such as panic disorder, social phobia, or generalized anxiety disorder).125,126 Further diagnoses (including ADHD and substance use disorders) should also be screened.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree