CHAPTER 37 Eating Disorders: Evaluation and Management

CLASSIFICATION

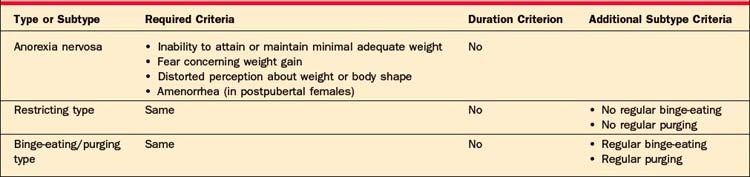

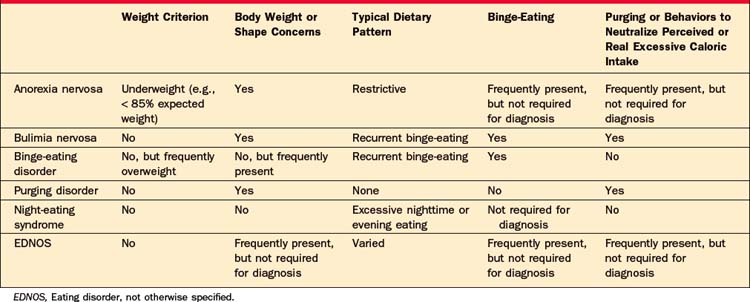

Current major diagnostic categories for eating disorders include anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), and eating disorder, not otherwise specified (EDNOS).1 In addition, research criteria for binge-eating disorder (BED) have been proposed and two disorders characterized by nocturnal eating (i.e., night-eating syndrome [NES]2 and nocturnal sleep-related eating disorder [NSRED]) have been described.3 AN has two subtypes (restricting and binge-eating/purging). BN also has two subtypes (purging and nonpurging). Recently, the conventional diagnostic classification for eating disorders has come under scrutiny. Whereas some have proposed additional disorders (e.g., purging disorder4), others have suggested that eating disorders should be lumped into one diagnostic category. Critics of the current classification argue that the most common type of eating disorder is the residual category, EDNOS. However, the heterogeneity within EDNOS and the dearth of related clinical trial data present challenges for both accurate diagnosis and effective treatment.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The incidence of eating disorders ascertained by case registries probably underestimates the true incidence for several reasons. Data from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) indicated that fewer than half of individuals with an eating disorder access any kind of health care service for their illness.5 Many of those affected are known to avoid or to postpone clinical care for the condition. In addition, both BN and BED may manifest without clinical signs, making them difficult, if not impossible, to recognize in a clinical setting without patient disclosure of symptoms, which may not be forthcoming.6 Furthermore, whereas AN may manifest with a variety of clinical signs, including emaciation, many patients effectively conceal their symptoms; up to 50% of cases of eating disorders may be missed in clinical settings.7 The lifetime prevalence of AN has been estimated from several large international twin cohorts (ranging from 0.5% to 2.2% for females).8 An estimate of the lifetime prevalence of AN combined with EDNOS resembling AN is over 3%.9 BN is more common than is AN with a reported lifetime prevalence in adult women ranging from 1.1% to 2.9%.5,10,11 An estimate of the lifetime prevalence of BN-like syndromes is considerably higher (8%).11 BED appears to be the most common eating disorder, with a lifetime prevalence ranging between 2.9% and 3.5% in females.5

The prevalence of eating disorders appears to vary by gender, ethnicity, and the type of population studied. Eating disorders are substantially more common among females than males.1 Binge-eating disorder is relatively more common among males (about 40% of cases), but still is more common in females.1 Eating disorders occur in culturally, ethnically, and socioeconomically diverse populations.

COURSE, CO-MORBIDITY, AND MORTALITY RATE

AN can have its onset from childhood to adulthood, but it most commonly begins in postpubertal adolescence. Likewise, the most common time of onset for BN is in postpubertal (usually late) adolescence. By contrast, BED typically has its onset later, in the early twenties. Both BN and BED can have their onset in later decades.5

Approximately half of those with AN and BN follow a chronic course, during which symptoms are moderate to serious.12,13 Notwithstanding the data and conventional wisdom that AN, in particular, often follows a chronic course, the NCS-R study reported that AN had a significantly shorter course than either BN or BED.5 These data suggest that there may be more variation in the course of AN than previously thought, possibly due to the fact that some individuals experience remission before seeking care. Similar to AN and BN, nearly half of individuals with BED remain symptomatic.14 Moreover, there is also considerable diagnostic migration among individuals from one eating disorder category to another, although little is known about the prognostic significance of this.

Eating disorders are associated with high medical co-morbidity (as nutritional derangement and purging behaviors frequently lead to serious medical complications); they are also associated with a high degree of psychiatric co-morbidity. The NCS-R study found that a majority of respondents with each of the major eating disorders (AN, BN, and BED) had a lifetime history of another psychiatric disorder. Of these, 94.5% of respondents with BN had a lifetime history of a co-morbid mental illness.5 The mortality risk associated with eating disorders is also elevated. The risk for premature death from AN and BN combined is tied (with substance abuse) for the highest among all mental illnesses.15 The high mortality rate is accounted for by both serious medical complications of the behaviors and by a high suicide rate (23 times the expected rate).16

ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS

Although the etiology of eating disorders is likely multifactorial, causal factors are uncertain.17 Possible sociocultural, biological, and psychological risk factors all have been identified, despite methodological limitations that characterize many studies and the low incidence of the eating disorders—especially AN. In addition to female gender and ethnicity, weight concerns and negative self-evaluation have the strongest empirical support as risk factors for eating disorders.17 In particular, risk factors for obesity appear to be associated with BED,18 and risk factors for dieting appear to be associated with BN.19 Risk for an eating disorder may also be elevated by generic risk factors for mental illness.17–19

Sociocultural factors are strongly suggested by population studies that have demonstrated that transnational migration, modernization, and Westernization are associated with an elevated risk for disordered eating among vulnerable subpopulations. Other social environmental factors (such as peer influence, teasing, bullying, and mass media exposure) have been linked with an elevated risk of body image disturbance or disordered eating.20

Numerous psychological factors have been identified as either risk factors or retrospective correlates of eating disorders. Among these is exposure to health problems (including digestive problems) in early childhood, exposure to sexual abuse and adverse life events, higher levels of neuroticism, low self-esteem, and anxiety disorders.17

Genetic influences on eating disorders have also been studied. Although family and twin studies support a substantial genetic contribution to the risk for eating disorders and molecular genetic studies hold promise, our understanding of the genetic transmission of risk for eating disorders remains limited. Future studies in the area will likely focus on the genetic underpinnings of symptoms associated with the eating disorders (rather than diagnoses), as well as gene-environment interactions.21 For example, data suggest that alterations in brain serotonin function,22 as well as differential cortical response to stimuli, may characterize eating disorders.23 Multiple heritable traits (e.g., appetitive behaviors, response to reward, impulsivity, and personality) likely predispose to an eating disorder.

DIAGNOSTIC FEATURES

Anorexia Nervosa

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is characterized and distinguished by a refusal to maintain, or attain, a minimally healthful body weight. A healthful body weight is assessed in relation to age, height, and sometimes gender and frame. Although the clinical context guides whether a particular weight is consistent with AN, a commonly recognized guideline is a weight that falls below 85% of that expected for height or a body mass index (BMI) less than 17.5 kg/m2 in adults. Whereas commenting on “ideal weight” in adults is relatively straightforward, there are no standardized tables or formulas available for children and adolescents. This is largely related to the fact that growth patterns are highly variable and can change on a monthly basis. Both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Psychiatric Association have set forth practice guidelines that encourage providers to determine an individual adolescent’s goal weight range using past growth charts, menstrual history, midparental height, and even bone age as guides. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends use of growth charts, which plot BMI for age (2 to 20 years) and gender. Children who fall below the fifth percentile in BMI for age are considered underweight, and those who fall between 5% and 85% are deemed “average weight.”24 Clearly, there is considerable variation in the “normal” range. Therefore, following the expected trajectory for a child based on the pediatrician’s past records is often most helpful.

In addition to a low body weight, AN is characterized in Western populations by a fear of becoming fat, and by a disturbance in body experience that can range from a denial of serious medical consequences to a distorted perception of one’s size and its importance. For postmenarchal females, amenorrhea of at least 3 months’ duration is a diagnostic criterion.

In children and adolescents, the diagnosis of AN can be made in the proper clinical context based on failure to attain minimally expected weight for height and age based on growth charts. Prepubertal females often do not enter puberty or attain menarche within the expected time frame.1 Stunted growth in terms of height is particularly concerning, and typically signals severe malnutrition. Of note, many physicians note that children and adolescents can be more sensitive to the medical consequences of eating disorders even when weight does not appear to be dangerously low.

Although in some populations, it is nearly culturally normative to be interested in maintaining a healthy body weight, and although dieting is widespread in the North American population, it is frequently the preoccupation with food that is the most distressing symptom for treatment-seeking patients. Cognitive symptoms can often be assessed by asking about dietary routines, food restrictions, and the patient’s desired body weight. Binge-eating and purging symptoms are common yet often overlooked in AN. The binge-eating/purging type of AN is diagnosed in the setting of recurrent binge-eating and purging; otherwise the diagnosis of restricting-type AN is made. Table 37-1 summarizes diagnostic criteria for AN.

Bulimia Nervosa

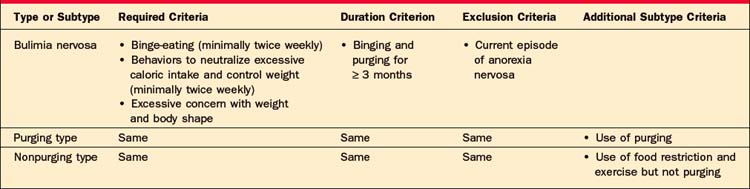

BN is characterized by recurrent episodes of binge-eating and behaviors aimed at the prevention of weight gain or purging calories. These behaviors, termed “inappropriate compensatory behaviors” in the DSM-IV-TR,1 include induced vomiting; laxative, enema, and diuretic misuse; stimulant abuse; diabetic underdosing of insulin; fasting; and excessive exercise. To meet criteria for the syndrome, patients need to engage in both binging and inappropriate compensatory behaviors at least twice weekly for at least 3 months. Two subtypes, “purging type” and “nonpurging type,” are distinguished. Individuals who prevent weight gain (by exercise or by fasting) fall into the latter subtype. In addition, individuals with BN are excessively concerned with body shape and weight. There can be considerable phenomenological overlap between individuals with BN and AN, binge-eating/purging type, although low weight is one helpful feature to draw a distinction between the two. A binge-eating episode is considered to take place in a discrete time period, consists of the intake of an unusually large amount of food given the social context, and is subjectively experienced as poorly controlled. Table 37-2 summarizes the diagnostic criteria for BN.

Binge-Eating Disorder

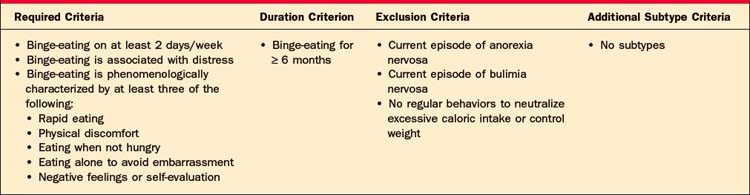

Binge-eating disorder (BED) is characterized by recurrent episodes of binge-eating. Unlike in individuals with BN, there are no recurrent behaviors to purge calories, or to prevent weight gain from the binge-eating episodes. Binge-eating episodes are accompanied by at least three of five correlates (these include eating rapidly, until uncomfortably full, when not hungry, alone to avoid embarrassment) and are associated with distress. Individuals must experience these episodes (on average) on 2 days each week for at least 6 months to meet provisional DSM criteria for BED. Table 37-3 summarizes provisional criteria for BED.

Eating Disorder, Not Otherwise Specified

This residual category comprises individuals who experience clinically significant symptoms that are atypical for, or do not meet full criteria for, AN and BN. These include BED, night-eating syndrome (NES), and purging disorder. Proposed criteria for NES include a 3-month or greater period of excessive evening or nighttime eating, morning anorexia, frequent nighttime awakenings (on at least 3 nights per week), and nighttime awakenings frequently associated with snacking on high-calorie food.2 Purging disorder is another recently proposed subtype of EDNOS that resembles BN but lacks binge-eating episodes that reach objective criteria for binges.4 Table 37-4 summarizes distinguishing diagnostic criteria of the eating disorders.

EVALUATION AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Evaluation of an eating disorder is optimally accomplished with input from mental health, primary care, and dietetic clinicians. Team management is advisable and often essential to clarify diagnosis, identify psychiatric and medical co-morbidities, and establish the modalities and level of care best suited to safe and effective management. Evaluation is often complicated by a patient’s ambivalence about accepting assistance or engaging in treatment. In other situations, it is more appropriate to discuss screening for an eating disorder as a patient may not realize that her behaviors are problematic, or may have not decided whether or how to disclose her symptoms.

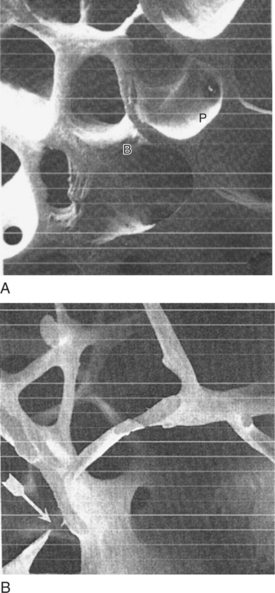

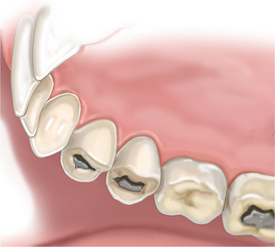

Because BN, BED, and EDNOS can present with a normal weight and physical examination, the diagnosis can be missed if a patient is not forthcoming or queried about symptoms. Among individuals who acknowledge eating and weight concerns, only a relatively small percentage report being asked by a doctor about symptoms of an eating disorder.6 Identification of an occult eating disorder in a primary care or mental health setting can be challenging if a patient is unreceptive to diagnosis or to treatment. Although screening assessments for eating disorders are more frequently used in research than in clinical settings, offering such an instrument in a primary care setting may provide a practical opportunity for a patient to discuss eating concerns. However, the validity of these assessments rests on a patient’s accurate and truthful responses. Certain clinical signs (e.g., a history of extreme weight changes, dental enamel erosion [Figure 37-1], parotid hypertrophy [Figure 37-2], or elevated serum amylase) may flag the possibility of an eating disorder, although the disorder can occur in their absence. Occasionally, certain probes in the clinical interview may suggest an eating disorder (Table 37-5). For example, inquiring about maximum, minimum, and desired weights often elicits information about body image concern, weight loss attempts, and overeating. Next, weighing a patient is essential for establishing the weight criterion for AN. The appropriateness of weight for height can be surprisingly difficult to estimate without this objective data. Although clinicians are sometimes reluctant to inquire about purging behaviors, a direct (empathically stated) question has been shown to be useful to elicit a candid response. Data suggest that even patients who have not voluntarily disclosed information to their doctor about an eating disorder are likely to disclose it in response to a direct query.6

Figure 37-1 Dental erosion resulting from chronic vomiting.

Adapted and printed with permission from the MGH Department of Psychiatry.

Figure 37-2 Parotid hypertrophy resulting from chronic vomiting.

Adapted and printed with permission from the MGH Department of Psychiatry.

Table 37-5 Useful Probes for Attitudes and Behaviors Associated with the Eating Disorders

| Topic | Suggested Probe Questions |

|---|---|

| Weight history | |

| Desired weight | • If you could weigh whatever you wanted without having to put effort into it, what would you like to weigh? |

| Perception of current shape and size | |

| Preoccupations | |

| Dietary patterns | |

| Binge-pattern eating | • Do you have episodes in which you feel you eat an unusual amount of food and it feels like you cannot control it? |

| Inappropriate compensatory behaviors | • Have you ever used ipecac? (To be followed with psychoeducational information about how dangerous it is.) • Do you use laxatives (especially stimulant type), suppositories, enemas, or diuretics to control your weight or compensate for calories you have taken in? • Do you use drugs (prescription or illegal) or caffeine to control your appetite or compensate for calories you have taken in? • (Assess adequacy of insulin dosing if diabetic; the nature of the probe used here will depend on the clinical context.) |

The history should elicit the onset of body image and eating disorder disturbances, specific precipitants, if any, and remissions or exacerbations of symptoms. The patient’s history of weight fluctuations, as well as minimum and maximum weights and their approximate durations, is useful in gauging how symptomatic the patient has become and where she is in relation to her illness history. For assessment of body image disturbance, it is useful to probe what the patient’s desired weight is in relation to her current weight. Moreover, probing how preoccupied she is with calories or her weight can include a straightforward question about it (as well as an inquiry about whether she keeps a running tally of calories in her head) or questions about how frequently she weighs herself or what effect a weight change has on her mood, self-efficacy, or self-evaluation. Alternatively, how a patient registers and responds to information about medical complications can also signal body image disturbance. Clinicians should ask about current dietary patterns, including a restrictive pattern of eating (e.g., fasting, meal-skipping, calorie restriction, or evidence of restricting intake of specific foods) and overeating (e.g., binge-eating, grazing, or night-eating). Excess water-drinking to produce “fullness” should be asked about and can lead to hyponatremia. In addition to dietary patterns, clinicians should inquire about and inventory attempts to compensate for binge-eating or to prevent weight gain (see Table 37-5). Some clinicians are reluctant to ask about certain symptoms, out of concern that they may introduce a weight loss strategy that a patient may be tempted to try. Unfortunately, patients have access to information about dieting, restrictive pattern eating, purging, and evasion of detection through content on “pro-ANA” (pro-anorexia) Web sites. Patients do not always appreciate how dangerous some behaviors (such as using ipecac) are; therefore, the clinical evaluation provides an invaluable opportunity to intervene in some behaviors that patients use or to suggest that they substitute them for others. Because untreated or poorly treated diabetes can result in weight loss, and because adherence to strict diets and food regimens is part of diabetes management, insulin-dependent diabetic patients present a special challenge in an evaluation. Often patients have been specifically referred for evaluation and management because their blood sugars are poorly controlled and their inappropriate underdosing or withholding of insulin has already come to light. For patients in whom these behaviors have not yet been identified, the most appropriate line of questioning may be more open-ended to determine how they manage their insulin dosing relative to food intake without necessarily suggesting that intentional hyperglycemia would cause weight loss. Excessive exercise is somewhat difficult to assess, as guidelines about the frequency and duration of exercise for health benefits have shifted upward. In this case, it is helpful to determine whether the exercise has a compulsive quality (e.g., does she exercise regardless of schedule, weather, injury, or illness) or is greatly in excess of medical or team recommendations.

Assessment of motivation for change is often critical for individuals with an eating disorder. Although individuals with BN and BED are often distressed by their symptoms, they often are fearful or reluctant about wanting to give them up. Individuals with AN are commonly unreceptive to treatment. Cognitive distortions that are typical of the illness make it difficult to motivate a patient to accept treatment that will restore weight. The prescription for recovery—which starts with weight restoration—is exactly what they fear. Moreover, denial of seriousness of medical complications of their low weight is often inherent to the illness; therefore, information that might motivate change under other illness scenarios is not effective for AN. In short, patients with AN are frequently highly invested in their symptoms and they are unwilling to occupy the conventional sick role, in which patients typically agree to treatment. In addition to sustaining a particular weight that they find acceptable, individuals with an eating disorder often find that their behavioral symptoms (restrictive eating that leads to hunger, binge-eating, or purging) contribute to self-soothing and to self-efficacy, and they are reluctant to relinquish these perceived benefits. Motivational enhancement therapy (MET) may be useful in priming patients to make use of therapy and in engaging treatment-resistant patients, as well as in reducing symptoms.25

Finally, mental health evaluation must take into account accompanying mood, thought, substance use, personality, and other disorders that are frequently co-morbid with eating disorders. Excessive use of alcohol and cigarettes should be determined as well. Behaviors associated with eating disorders are frequently exacerbated by depression and by anxiety disorders. Conversely, an increase in the frequency or severity of eating disorder symptoms can exacerbate mood symptoms. Moreover, low weight undermines the efficacy of antidepressant therapy on mood symptoms. This may be due to nutritional or other unknown factors. Substance abuse sometimes waxes and wanes in relation to disordered eating. A clinician who evaluates a patient with active substance abuse or in early recovery is advised to use particular caution in considering the impact of controlling restrictive eating, binging, or purging symptoms if these patterns provide an essential coping mechanism for a patient at risk of relapse for substance abuse or other self-injurious behavior. If the symptoms co-exist, generally the more life-threatening of them will require initial treatment. For BN and BED, the substance abuse disorder generally takes precedence, but the medical and nutritional impact of the eating symptoms requires ongoing surveillance. For severe AN in the setting of substance abuse, it is highly likely that inpatient care is the safest and most effective treatment setting. Finally, assessment of suicidal ideation and behavior is critical in the evaluation of an eating disorder. As noted previously, suicide rates are elevated in eating disorders and the risk and prevention of suicide should always be considered.16

MEDICAL COMPLICATIONS

Medical consequences of eating disorders are often occult, yet dangerous. Even subtle laboratory abnormalities, while not intrinsically harmful or worrisome in other settings, may reflect physiological tolls indicative of significant illness. Medical complications affect many other organ systems and are listed in Table 37-6.

Table 37-6 Selected Important Medical Complications of the Eating Disorders

| Metabolic |

| Hypokalemia Hyponatremia, hypernatremia Hypophosphatemia; hyperphosphatemia Ketonuria |

| Endocrine |

| Euthyroid sick syndrome Amenorrhea, oligomenorrhea |

| Skeletal |

| Osteopenia/osteoporosis (rarely fully reversible) Impaired peak bone mass |

| Developmental |

| Growth arrest, short stature Delayed puberty, delayed menarche |

| Reproductive |

| Oligomenorrhea Infertility Miscarriage Increased rate of cesarian sections Increased risk for postpartum depression Intrauterine fetal growth and birth weight Decreased neonatal Apgar scores |

| Dermatological |

| Acrocyanosis Carotenemia Brittle hair and nails Xerosis Pruritus Lanugo Hair loss |

| Cardiovascular |

| Decreased left ventricular mass Decreased chamber size Decreased contractility Decreased stroke volume Decreased cardiac output Decreased exercise response Increased ventricular ectopy Pericardial effusion (small) Bradycardia Orthostatic and nonorthostatic hypotension Dysrhythmias Electrocardiogram (ECG) abnormalities (as in Table 37-11) Acquired (reversible) mitral valve prolapse Ipecac cardiomyopathy Congestive heart failure |

| Gastrointestinal |

| Reflux esophagitis Mallory-Weiss tear (usual cause of hematemesis) Esophageal or gastric rupture (rare but often lethal) Gastroparesis (often symptomatic) Laxative abuse colon Rectal bleeding Superior mesenteric artery syndrome Abnormal liver enzymes with fatty infiltration Pancreatitis Functional gastrointestinal disorders |

| Neurological |

| Seizures Myopathy Peripheral neuropathy Cortical atrophy |

| Immunological |

| Blunted febrile response to infection Impaired cell-mediated immunity |

| Hematological |

| Bone marrow suppression |

| Renal |

| Renal calculi Acute: azotemia Long-term complication: renal failure from chronic hypokalemia |

Cardiac consequences of anorexia may be asymptomatic but can turn lethal. Adolescents appear to be particularly at risk.26 Myocardial hypotrophy occurs, often early, with reduced left ventricular mass and output.27 The heart of the patient with anorexia has an impaired ability to respond to the increased demands of exercise. Hypotension occurs early and orthostasis follows, possibly enhanced by volume depletion. Bradycardia is common, probably due to increased vagal tone. This should neither be dismissed as innocent, nor be viewed as comparable to that in conditioned athletes. Whereas athletes with bradycardia have increased ventricular mass and myocardial efficiency, in anorexia (even in prior athletes), bradycardia reflects cardiac impairment associated with reduced stroke volume.

Further changes are seen in cardiac anatomy and conduction. Compression of the annulus from reduced cardiac mass may result in mitral valve prolapse, and silent pericardial effusions are common, but generally not of functional significance.28 Electrophysiologically, the QTc interval and QT dispersion may be increased,29 and may predispose to ventricular arrhythmias and be harbingers of sudden death.30 Patients who use ipecac to induce vomiting are at risk of a life-threatening cardiomyopathy caused by the emetine in this product. While virtually all aspects of cardiac function normalize with full recovery, some aspects of cardiac function may actually deteriorate during initial treatment.31

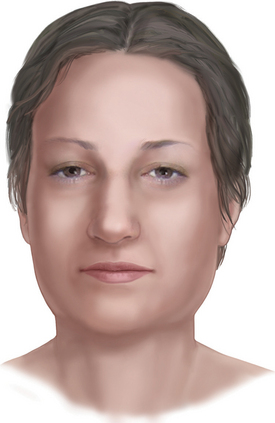

Although cardiac complications may be the most dangerous for AN patients, osteoporosis is among the most permanent. Loss of bone mass can be rapid and remain low despite disease recovery; it represents a life-long risk of increased fractures. The association of low bone mineral density (BMD) is established in adolescent girls as well as boys.32,33 Of importance, effects on bone mass can be seen with brief disease duration, with very significant reductions in bone mass being reported in girls who have been ill for less than a year. Skeletal impact can be severe.34 An electron micrograph of an osteoporotic female with multiple vertebral compression fractures is shown in Figure 37-3.