CHAPTER 39 Personality and Personality Disorders

OVERVIEW

The last 25 years have witnessed a remarkable increase in research on, and clinical interest in, personality disorders. Personality disorders are common conditions that affect between 10% and 15% of the general population.1 Furthermore, between 25% and 50% of individuals who seek outpatient mental health care have either a primary or co-morbid personality disorder. The percentage of psychiatric inpatients with a personality disorder is estimated to be approximately 80%. Personality disorders as a group are among the most frequent disorders treated by psychiatrists.2

PERSONALITY THEORY

Gordon Allport,3 the father of personality psychology, defined personality as “the dynamic organization within the individual of those psychophysical systems that determine his characteristic behavior and thought.” Understanding what personality is focuses on building comprehensive definitions such as the following: personality is a stable, organized system composed of perceptual, cognitive, affective, and behavioral subsystems that are hierarchically arranged and that determine how human beings understand and react to others socially. While such a definition has academic merit, it lacks clinical utility. A more useful way of understanding personality is to operationally define it by its functions. One of the chief functions of personality is to guide and regulate our dyadic interpersonal relationships and our small group social interactions. Smooth interpersonal relationships and effective social interactions are crucial to successful life adaptation and to achievement. Evolutionary psychologists believe that personality evolved because improved social and interpersonal function allowed for more effective solutions to the primary problems of human existence (i.e., obtaining food, shelter, protection, and access to reproduction).4,5 The specific psychological “structures” (functions) and interpersonal skills that allowed our distant ancestors to solve these survival problems evolved into what we now recognize as personality. The evolution of personality, with its emphasis on social effectiveness, may represent one of the more successful survival strategies of our species.4 Clinically, the advantage of viewing the primary function of personality as the facilitation of effective social and interpersonal interactions is that it allows us to identify when personality becomes disordered: personality is disordered when it interferes with, or complicates, social and interpersonal function.

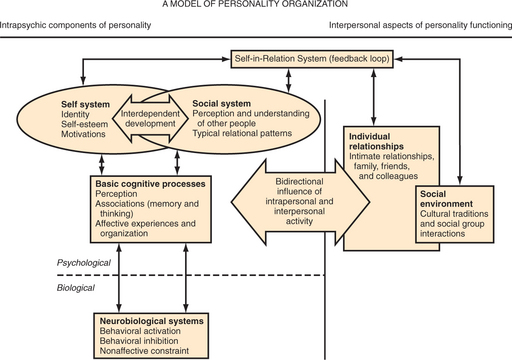

Guided by the work of Mayer,6 we can hypothesize that the following three psychological subsystems need to develop for personality to achieve its primary goal of guiding effective social and interpersonal function:

These components seem to be the irreducible minimum of personality subsystems required for maintenance and regulation of interpersonal function. Figure 39-1 provides a model of personality that uses these three components. The model highlights the fact that personality arises from a combination of complex reciprocal intrapersonal and interpersonal processes that occur simultaneously as we interact with others. Figure 39-1 also shows how these components are organized around, and influenced in an ongoing manner by, the maturation and ongoing function of basic cognitive capacities (such as memory, perception, and logical reasoning [association, analysis, and synthesis]).

THE ORIGINS OF PERSONALITY

From birth, infants exhibit differences in activity levels, novelty approach and avoidance, and stimulus threshold. These differences reflect a child’s unique temperament. Temperament is thought to be the purest expression of the biological basis of personality. Kagan7 and colleagues have identified two distinct temperaments (inhibited or uninhibited) in infants. These two temperaments reflect the degree to which infants are fearful of new and unfamiliar situations, and may represent the human version of a universal mammalian tendency for individuals within a species to vary in the degree to which they either approach or avoid unfamiliar situations.

Research with adults has identified three basic temperaments: positive emotionality, negative emotionality, and constraint.8–10 Positive emotionality and negative emotionality10 are similar to Kagan’s inhibited and uninhibited temperaments. Like the inhibited child, the adult who has high negative emotionality tends to perceive and react to the world as if it were a threatening, problematic, and upsetting place,10 whereas adults who have high positive emotionality are more physically active, happy, and self-confident. Positive emotionality and negative emotionality are primarily associated with the affective tone of an individual’s life. Constraint refers to how easily an individual acts on an initial emotionally based evaluation of events and people. In other words, constraint reflects the degree of control an individual exerts over those parts of behavior that are driven by emotion, and can be viewed as the buffering capacity operating in response to emotions. Adults who have a high level of constraint are able to resist their initial impulse to avoid (negative emotionality) or approach (positive emotionality) a person or situation. This delay allows for the opportunity to evaluate the possible long-term implication of behaviors.10 Adults who have a low level of constraint, however, act quickly or impulsively on their initial emotional evaluation, and either approach or avoid a person or situation. Constraint may be a precursor to or foundation of the adult personality trait of conscientiousness.

The neurobiological network underlying positive emotionality is considered a behavior activation system (BAS).10,11 The BAS is highly sensitive to the effects of positive reinforcement, particularly unconditioned reinforcers (such as food, sex, and safety). With increased cognitive development, the BAS becomes sensitive to the effects of complex secondary (conditioned) reinforcers (e.g., money and social status). The BAS regulates behavior patterns designed to find, identify, and obtain these desired reinforcements. Simply put, the BAS is reward directed.11 Depue12 and Pickering and Gray11 have suggested that the ascending dopamine (DA) systems found in mesolimbic and mesocortical regions of the brain, long implicated in reward-directed behavior, underlie the BAS.

Negative emotionality, on the other hand, is associated with behavioral inhibition10,12 and the affective experience of anxiety and fear. The neurobiological network that underlies negative emotionality is a behavior inhibition system (BIS). Norepinephrine activity in the locus coeruleus appears to underlie the BIS.10,12

The neurobiology of constraint is less clear. However, if constraint functions as a response-threshold modifier, neurotransmitters associated with tonic inhibition would likely underlie the trait. Serotonin (5-HT) appears to play a major role in the modulation of a diverse set of functions that includes emotions, motivation, and sensory reactivity.12 Reduced 5-HT function in animals and humans has been associated with increased irritability, hypersensitivity to sensory stimulation, and impulsivity. From these data, it is plausible that 5-HT networks play a major role in constraint.

Childhood temperament, with its innate, neurobiologically-based behavioral patterns, plays a primary role in the development, expression, and modification of adult personality. Indeed, evidence suggests that there is a moderate degree of stability of childhood temperament through adolescence and into early adulthood.7 However, the development of adult personality is a complex process that involves more than just biological endowment. In fact, as we mature, the non–biologically-based contributions to personality become more influential and more evident in our behavior.

ADULT PERSONALITY TRAITS

Since the mid-1930s, psychologists have devised a number of “dimensional” or “trait” models of adult personality. These models hypothesize that normal personality is composed of between three13 and sixteen14 broadly defined traits. Recently, there has been growing agreement that normal adult personality can be adequately described using the Five-Factor Model (FFM).15–17 The FFM is based on the premise that language is the “fossil record” of the personality component of evolutionary psychology. Because language is important for life success in human beings, words had to evolve for all the important observable personality traits. To test this assumption, factor analysis has been used to reduce large lists of descriptive words to their basic psycholinguistic structures. In several such studies, five broad groupings of these trait words have been found. Similar five-factor structures have also been obtained across ethnic groups and languages. The FFM does not argue that all personality traits are represented within the broad domains; however, it provides a reasonably comprehensive coverage of the most important traits that people use to describe themselves and others.18 The most common names given to these categories are neuroticism, extroversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness.

Openness describes an individual’s interest in, or willingness to engage in, new and varied intellectual and cultural experiences. It is a reflection of curiosity and imagination; it should not to be confused with extroversion. Individuals who are high in openness enjoy a wide range of intellectual and cultural experiences (such as art, theater, poetry, and philosophy). Individuals who are low on this trait, however, may be no less intelligent, but have less interest in esoteric intellectual pursuits. Rather, they concentrate on learning and on experiences that are more practical and applicable to their life. The relationship of openness to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) personality disorders is less clear than it is to the other four factors of the FFM.

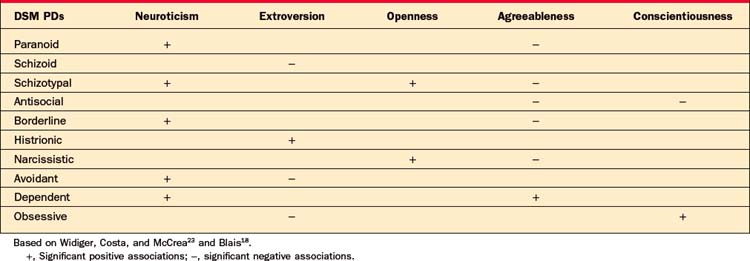

While the relationship of the DSM-IV personality disorders to temperament and to the FFM personality traits remains unclear, there are persuasive data from many different lines of research that indicate that the FFM dimensions are related to the DSM-IV personality disorders.19–22 Table 39-1 provides empirically demonstrated associations among the DSM-IV personality disorders and the domains of the FFM. As Table 39-1 indicates, either alone or in combination, extreme (high or low) forms of these dimensions can explain and deepen our understanding of the DSM-IV personality disorders. For example, the DSM-IV category of borderline personality disorder reflects a combination of both high neuroticism and low agreeableness, histrionic personality disorder is associated with excessive extroversion, and antisocial personality disorder involves low levels of agreeableness and conscientiousness.

Table 39-1 Relationship of the DSM-IV Personality Disorders (DSM PDs) to the Five-Factor Model Domains

Any attempt to integrate the DSM personality disorders with the FFM domains requires some understanding of the conflicts (both historically and conceptually) between the categorical and dimensional approaches to personality.23 Medicine has traditionally relied on categorical diagnostic systems for the identification of the presence of a disorder. The categorical approach assumes categories with relatively definite boundaries—“sick” versus “well,” pneumonia versus congestive heart failure, schizophrenia versus bipolar disorder, manic episode. It goes back at least to Plato’s attempts to “carve nature at the joints.” However, categorical models assume that the distribution of the condition is discontinuous (such as pregnancy or death, where there is no gradation). This black-or-white approach contains assumptions that are hard to support (or are even quite misleading) for the personality disorders.

Despite these differences, it seems likely that future versions of the DSM will incorporate some form of a dimensional model into the personality disorder system. In fact, recent findings reveal that a four-factor structure nicely accounts for abnormal personality traits (traits more directly linked to the DSM personality disorders) than to either current systems or the FFM. These factors (emotional dysregulation, dissocial behaviors, inhibition, and compulsivity) closely resemble four of the FFM domains.24 Shedler and Weston25 have also developed a dimensional model for the description and diagnosis of personality disorders that holds considerable clinician utility.

Cloninger and Svrakic8 have developed an alternative dimensional model that attempts to account for variations in both normal and abnormal personality. Building on the pioneering ideas of Thomas and Chess, Cloninger and Svrakic’s model identifies four basic genetically determined temperaments (harm avoidance, novelty seeking, reward dependence, and persistence) and three character traits (self-directedness, cooperativeness, and self-transcendent). These seven dimensions interact to form personality. The Temperament and Character Inventory was developed to assess the seven main components and additional subcomponents of the model. This comprehensive model of personality combines findings from the fields of genetics, neurobiology, and trait psychology in a manner that can enhance both the assessment and treatment of personality disorders. Cloninger and Svrakic’s ambitious work has generated considerable research activity but has not been as widely adopted clinically.

DSM-IV PERSONALITY DISORDERS

The DSM-IV-Text Revision (TR)26 recognizes ten major personality disorders, which are organized into three clusters (based on shared diagnostic features): (1) cluster A personality disorders, which share the common features of being odd and eccentric (paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal personality disorders); (2) cluster B personality disorders, which share the common features of being dramatic, emotional, and erratic (antisocial, borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic personality disorders); and (3) cluster C personality disorders, which share the common features of being anxious and fearful (avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders). As a rule, patients often display traits of more than one personality disorder, and if they meet diagnostic criteria for another one, it should be diagnosed along with the primary one.

Cluster A Personality Disorders

Schizotypal Personality Disorder

The differential diagnosis for schizotypal personality disorder includes schizophrenia and several personality disorders. Paranoid and schizoid personality disorders share many of the core features of schizotypal personality disorder, but differ by degree or absence of eccentricity. Borderline personality disorder shares some of the unusual speech and perceptual style, but it demonstrates stronger affect and connection to others. Patients with avoidant personality disorder, while uncomfortable and inept in social settings, are not eccentric and crave contact with others. Schizophrenia differs from schizotypal personality disorder in that the schizotype possesses good reality testing and lacks psychosis.