CHAPTER 41 The Pharmacotherapy of Anxiety Disorders

OVERVIEW

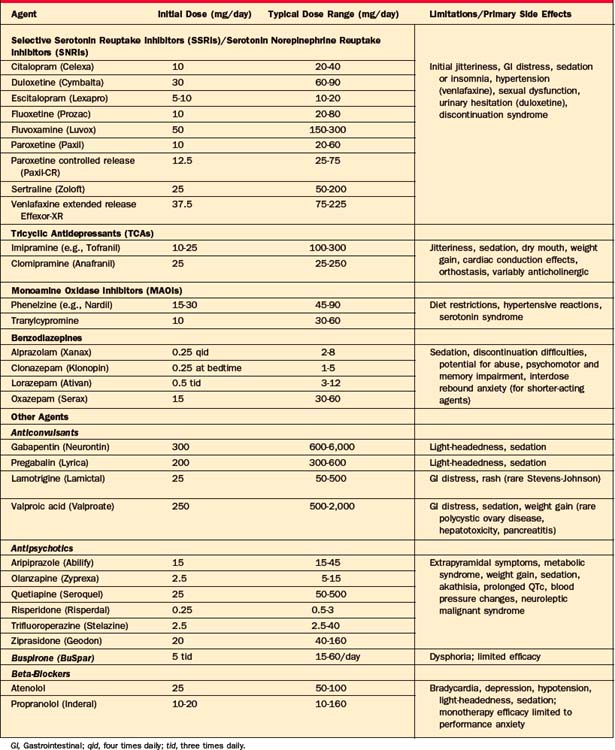

As described elsewhere in this volume (see Chapter 32), anxiety disorders are associated with both significant distress and dysfunction. In this chapter we will review the pharmacotherapy of panic disorder (with or without agoraphobia), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and social anxiety disorder (SAD); the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is discussed in Chapter 34, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is discussed in Chapter 33. Table 41-1 includes dosing information and common side effects associated with the pharmacological agents commonly used for the treatment of anxiety, referred to in the following sections.

PANIC DISORDER AND AGORAPHOBIA

Antidepressants

The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) have become first-line agents for the treatment of panic disorder and other anxiety disorders because of their broad spectrum of efficacy (including benefit for disorders commonly co-morbid with panic disorder, such as major depression), favorable side-effect profile, and lack of cardiotoxicity. Currently, paroxetine (both the immediate [Paxil] and controlled-release [Paxil CR] formulations), sertraline (Zoloft), fluoxetine (Prozac), and extended-release venlafaxine (Effexor-XR) are Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for the treatment of panic disorder, though other SSRIs, including citalopram (Celexa), escitalopram (Lexapro), and fluvoxamine (Luvox), have also demonstrated antipanic efficacy in both open and double-blind trials. A recently introduced SNRI, duloxetine, has also been reported to be effective for panic disorder in case reports, though no randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are currently reported.1 While the majority of data supporting the efficacy of pharmacological agents for panic disorder derive from short-term trials, several long-term studies have also demonstrated sustained efficacy over time.2

Because the SSRIs/SNRIs have the potential to cause initial restlessness, insomnia, and increased anxiety, and because panic patients are commonly sensitive to somatic sensations, the starting doses should be low, typically half (or less) of the usual starting dose (e.g., fluoxetine 5 to 10 mg/day, sertraline 25 mg/day, paroxetine 10 mg/day [or 12.5 mg/day of the controlled-release formulation], controlled-release venlafaxine 37.5 mg/day), to minimize the early anxiogenic effect. Doses can usually begin to be raised, after about a week of acclimation, to achieve typical therapeutic levels, with further gradual titration based on clinical response and side effects, although even more gradual upward titration is sometimes necessary in particularly sensitive or somatically focused individuals. Although the nature of the dose-response relationship for the SSRIs in panic is still being assessed, available data support doses for this indication in the typical antidepressant range, and sometimes higher, that is, fluoxetine 20 to 40 mg/day, paroxetine 20 to 60 mg/day (25 to 72.5 mg/day of the controlled-release formulation), sertraline 100 to 200 mg/day, citalopram 20 to 60 mg/day, escitalopram 10 to 20 mg/day, fluvoxamine 150 to 250 mg/day, and controlled-release venlafaxine 75 to 225 mg/day (although some patients may respond at lower doses). In some cases of refractory panic, even higher doses may be clinically useful, although additional data examining such dosing is needed.

SSRI and SNRI administration may be associated with adverse effects that include sexual dysfunction, sleep disturbance, weight gain, headache, dose-dependent increases in blood pressure (with venlafaxine), gastrointestinal disturbance, and provocation of increased anxiety (particularly at initiation of therapy) that may make their administration problematic for some individuals.3–5 The SSRIs/SNRIs are usually administered in the morning (though for some individuals, agents such as paroxetine and others may be sedating and better tolerated with bedtime dosing); emergent sleep disruption can usually be managed by the addition of hypnotic agents. The typical 2- to 3-week lag in onset of therapeutic efficacy for the SSRIs/SNRIs can be problematic for acutely distressed individuals. There is no clear evidence of a differential efficacy between agents in the SSRI and SNRI classes to guide selection, although there are potentially relevant differences in their side-effect profiles (e.g., potential for weight gain and discontinuation-related symptomatology), differences in their potential for drug interactions, and the availability of generic formulations that may be clinically relevant.6,7 Results from one randomized placebo-controlled trial study demonstrated comparable efficacy for venlafaxine at 75 and 150 mg/day compared to 40 mg/day of paroxetine,8 whereas another reported greater efficacy on some, but not all, measures for venlafaxine 225 mg/day compared to 40 mg/day of paroxetine, suggesting the possibility of greater efficacy for the SNRI at higher doses.8

Tricyclic Antidepressants

Imipramine (Tofranil) was the first pharmacological agent shown to be efficacious in panic disorder, and the tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) were typically the first-line, “gold standard” pharmacological agents for panic disorder until they were supplanted by the SSRIs, SNRIs, and benzodiazepines. Numerous RCTs demonstrate the efficacy of imipramine and clomipramine for panic disorder, with supportive evidence for other TCAs.9,10 There is some evidence that clomipramine may have superior antipanic properties when compared with the other TCAs, possibly related to its greater potency for serotonergic uptake. The efficacy of the TCAs is comparable to that of the newer agents11–13 for panic disorder, but they are now used less frequently due to their greater side-effect burden,14 including associated anticholinergic effects, orthostasis, weight gain, cardiac conduction delays, and greater lethality in overdose. The side-effect profile of the TCAs is associated with a high dropout rate (30% to 70%) in most studies. The SSRIs/SNRIs appear to have a broader spectrum of efficacy than the TCAs, which are less efficacious for conditions such as SAD15 and, with the exception of the more serotonergic TCA, clomipramine, less effective for OCD. This is of particular importance as both SAD and OCD may present with co-morbid panic disorder.

Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors

Despite their reputation for efficacy, the monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) have not been systematically studied in panic disorder as defined by the current nomenclature; there is, however, at least one study predating the use of current diagnostic criteria that likely included panic-disordered patients and reported results consistent with efficacy for the MAOI phenelzine.16 Although clinical lore suggests that MAOIs may be particularly effective for patients with panic disorder refractory to other agents, there are no data to address this issue. Because of the need for careful dietary monitoring (including proscriptions against tyramine-containing foods and ingestion of sympathomimetic and other agents) to reduce the risks of hypertensive reactions and serotonin syndrome, the MAOIs are typically used after lack of response to safer and better-tolerated agents.17,18 Use of MAOIs is also associated with a side-effect profile that includes insomnia, weight gain, orthostatic hypotension, and sexual disturbance.

Optimal doses for phenelzine range between 60 and 90 mg/day, while doses of tranylcypromine generally range between 30 and 60 mg/day. Though reversible inhibitors of monoamine oxidase–A (RIMAs) have in general a more benign side-effect profile and lower risk of hypertensive reactions than irreversible MAOIs (such as phenelzine), RCTs of brofaromine and of moclobemide in panic disorder report inconsistent efficacy; neither agent has become available in the United States.19–23 A transdermal patch for the MAOI selegiline (that does not require dietary proscriptions at its lowest dose) became available in the United States with an indication for treatment of depression; to date, systematic evaluation of its efficacy for panic or other anxiety disorders has not been reported.

Benzodiazepines

Despite guidelines24 for the use of antidepressants as first-line antipanic agents, benzodiazepines are still commonly prescribed for the treatment of panic disorder.25,26 Two high-potency benzodiazepines, alprazolam (immediate and extended-release forms) and clonazepam, are FDA-approved for panic disorder; however, other benzodiazepines of vary-ing potency, such as diazepam,26,27 adinazolam, and lorazepam,28–30 at roughly equipotent doses have also demonstrated antipanic efficacy in RCTs. Benzodiazepines remain widely used for panic and other anxiety disorders, likely due to their effectiveness, tolerability, rapid onset of action, and ability to be used on an as-needed basis for situational anxiety. It should be noted, however, that as-needed dosing for monotherapy of panic disorder is rarely appropriate, because this strategy generally exposes the patient to the risks associated with benzodiazepine use without the benefit of adequate and sustained dosing to achieve and maintain comprehensive efficacy. Further, from a cognitive-behavioral perspective, as-needed dosing engenders dependency on the medication as a safety cue and interferes with exposure to and mastery of avoided situations.

Despite their generally favorable tolerability, benzodiazepines may be associated with side effects that include sedation, ataxia, and memory impairment (particularly problematic in the elderly and those with prior cognitive impairment).31 Despite concerns that ongoing benzodiazepine administration will result in the development of therapeutic tolerance (i.e., loss or therapeutic efficacy or dose escalation), available studies of their long-term use suggest that benzodiazepines remain generally effective for panic disorder over time,32,33 and do not lead to reports of significant dose escalation.34 However, even after a relatively brief period of regular dosing, rapid discontinuation of benzodiazepines may result in significant withdrawal symptoms (including increased anxiety and agitation)35; for instance, in one study, over two-thirds of patients with panic disorder, discontinuing alprazolam, experienced a discontinuation syndrome.36 Discontinuation of longer-acting agents (such as clonazepam) may result in fewer and less intense withdrawal symptoms with an abrupt taper. Patients with a high level of sensitivity to somatic sensations may find withdrawal-related symptoms particularly distressing, and a slow taper as well as the addition of CBT37 during discontinuation may be helpful to reduce distress associated with benzodiazepine discontinuation. A gradual taper is recommended for all patients treated with daily benzodiazepines for more than a few weeks, to reduce the likelihood of withdrawal symptoms (including, in rare cases, seizures). Though individuals with a predilection for substance abuse38 are at risk for abuse of benzodiazepines, those without this diathesis do not appear to share this risk.34 However, benzodiazepines and alcohol may negatively interact in combination,39 and the concomitant use of benzodiazepines in patients with current co-morbid alcohol abuse or dependence can be problematic (thus, further supporting the use of antidepressants as first-line antipanic agents in this population with co-morbid illness). In addition, given the high rates of co-morbid depression associated with panic disorder, it is worth noting that benzodiazepines are not in general effective for treatment of depression and may in fact induce or intensify depressive symptoms in those with co-morbid depression.40

Although benzodiazepines are commonly prescribed for the treatment of panic disorder, benzodiazepine monotherapy has decreased somewhat.25 Treatment with a combination of an antidepressant and a benzodiazepine compared to an antidepressant alone results in acceleration of therapeutic effects as early as the first week, although by weeks 4 or 5 of treatment, combined treatment (whether maintained or tapered and discontinued) shows no advantage over monotherapy.41,42 Thus, the data suggest that co-administration improves the rapidity of response when co-initiated with antidepressants, but that ongoing use may not be necessary after the initial weeks of antidepressant pharmacotherapy. The issue of whether augmentation with a benzodiazepine for an individual who remains symptomatic on antidepressant monotherapy is effective has not been systematically assessed, although the strategy appears to be helpful in practice.

Other Agents

The data addressing the potential efficacy of bupropion (a relatively weak reuptake inhibitor of norepinephrine and dopamine) for the treatment of panic disorder is mixed, with a small study of the immediate-release formulation administered at high doses demonstrating no benefit,43 but a more recent open-label study employing standard doses of the extended-release formulation suggesting potential benefit.44 Similarly, there is mixed support for the potential efficacy for panic disorder of another noradrenergic agent, reboxetine,45 with a comparative study demonstrating the efficacy of both reboxetine and paroxetine, though suggesting that the SSRI may be more efficacious.46

There is suggestive evidence from case reports that buspirone (an azapirone 5-HT1A partial agonist) may be useful as an adjunct to antidepressants and benzodiazepines47 and acutely, although not over the long-term, to CBT48 for panic disorder, but appears to be ineffective as monotherapy.49,50

Beta-blockers reduce the somatic symptoms of arousal associated with panic and anxiety, but may be more useful as augmentation for incomplete response rather than as initial monotherapy.51 Pindolol, a beta-blocker with partial antagonist effects at the 5-HT1A receptor, was effective in a small double-blind RCT52 of patients with panic disorder remaining symptomatic despite initial treatment.

Atypical antipsychotics including olanzapine,53 risperidone,54 and aripiprazole55 have demonstrated potential efficacy as monotherapy or as augmentation for the treatment of patients with panic disorder refractory to standard interventions in a number of small, open-label trials or case series. However, evidence for treatment-emergent weight gain, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes with some of the atypical agents, as well as the lack of large RCTs examining their efficacy and safety in panic disorder to date, does not support the routine first-line use of these agents for panic disorder, but rather consideration for patients whose panic disorder has not sufficiently responded to standard interventions.

On the basis of limited data, some anticonvulsants appear to have a potential role in the treatment of panic disorder, in individuals with co-morbid disorders (such as bipolar disorder and substance abuse), for which the use of antidepressants and benzodiazepines, respectively, is associated with additional risk. Small studies support the potential efficacy of valproic acid,56,57 but not carbamazepine,58 for the treatment of panic disorder. Gabapentin did not demonstrate significant benefit compared to placebo for the overall sample of patients with panic disorder in a large RCT, but a post hoc analysis found efficacy for those with at least moderate panic severity.59 Another related compound, the alpha2-delta calcium channel antagonist pregabalin, has demonstrated utility for GAD,60 but there are no published reports to date in panic disorder.

GENERALIZED ANXIETY DISORDER

Antidepressants

SSRIs and SNRIs

As is true for panic and the other anxiety disorders, the SSRIs and SNRIs are generally considered first-line agents for the treatment of GAD because of their favorable side-effect profile compared to older antidepressants (e.g., TCAs), lack of abuse or dependency liability compared to the benzodiazepines, and a broad spectrum of efficacy for common co-morbidities, such as depression. Similar to considerations for their use in individuals with panic disorder, SSRIs, SNRIs, and other antidepressants should be initiated in patients with GAD at half or less than the usual starting dose in order to minimize jitteriness and anxiety. Currently, the SSRIs paroxetine and escitalopram and the SNRIs (including the extended-release formulation of venlafaxine [Effexor-XR] and duloxetine [Cymbalta]) have received FDA approval for GAD; however, all agents in these classes are likely effective for GAD without convincing evidence for significant divergence in efficacy between them, but with some differences in their side-effect profiles.61 Long-term trials with SSRIs and SNRIs demonstrate that continued treatment for 6 months is associated with significantly decreased rates of relapse relative to those who discontinued the drug following acute treatment; further, ongoing treatment appears to be associated with continued gains in the quality of improvement as evinced by a greater proportion of individuals reaching remission over time.62,63

Tricyclic Antidepressants

A number of studies have demonstrated the efficacy of the prototypic TCA imipramine for the treatment of GAD, with RCTs showing generally comparable efficacy but slower speed of onset relative to a benzodiazepine comparator,64 and a greater side-effect burden relative to an SSRI comparator.65