CHAPTER 44 Pharmacological Approaches to Treatment-Resistant Depression

OVERVIEW

Major depressive disorder (MDD) has a lifetime prevalence of between 17% and 21%, with about twice as many women affected as men.1 In any 12-month period, the prevalence of MDD is about 6.7%, with over 80% of those with MDD having moderate to severe depression.2 Unfortunately, most patients do not receive timely treatment,3 even though the disorder disrupts function at work, home, and school.4 The National Comorbidity Replication (NCR) study showed that about 38% of those who experience an episode of major depression receive at least minimally adequate care in mental health specialty or general medical settings,5 while the majority of patients receive inadequate treatment. For those patients who receive adequate pharmacotherapy, it is estimated from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of antidepressants that only about 30% to 40% will achieve full remission (absence or near absence of symptoms); the rest fail to reach remission.6 About 10% to 15% fail to respond (with at least a 50% improvement).7 Nonresponse is associated with disability and higher medical costs, and partial response or response without remission is associated with higher relapse and recurrence rates.8–10 Thus, MDD is a frequent and serious disorder that usually responds partially to treatment and leaves many patients with treatment resistance. This chapter reviews and critically evaluates how we define treatment-resistant depression (TRD) and reviews the evidence for the management of TRD, examining pharmacological approaches to alleviate the suffering of patients who insufficiently benefit from initial treatment.

TRD typically refers to the occurrence of an inadequate response among patients who suffer from unipolar depressive disorders following adequate antidepressant therapy. What constitutes inadequate response has been the subject of considerable debate in the field, and most experts would now argue that an inadequate response is the failure to achieve remission. Although the more traditional view of treatment resistance has focused on nonresponse (e.g., a patient who reports minimal or no improvement), from the perspective of clinicians and patients/consumers, not achieving remission despite adequate treatment represents a significant challenge. In addition, response without remission has a potentially worse outcome, as residual symptoms are associated with worse outcome and increased relapse risk.9–11 Finally, response without remission following antidepressant treatment is associated with a significantly greater number of somatic symptoms than are found in remission and with impaired social function.12,13 For these reasons, it has been argued that “complete remission should be the goal in the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD), because it leads to a symptom-free state and a return to premorbid levels of functioning.”14 With this treatment approach in mind, inadequate response implies that the treatment failed to achieve remission. Several operational definitions of remission have been proposed, but, from the clinician’s and patient’s perspective, remission typically implies achieving a relatively asymptomatic state.15

What Constitutes Adequate Antidepressant Therapy?

Adequate antidepressant therapy is typically considered to consist of one or more trials with antidepressant medications with established efficacy in MDD. In addition, such trials need to involve doses considered to be effective (e.g., superior to placebo in controlled clinical trials) and their duration needs to be sufficient to produce a robust therapeutic effect (e.g., 12 weeks or longer).16

The Thase and Rush Model of Staging Treatment Resistance

Thase and Rush first proposed a model of staging the various levels of resistance in TRD.17 However, several methodological issues exist with respect to this model. First, the degree of intensity of each trial (in terms of dosing, duration, or both) is not accounted for. For example, a trial with high doses of an antidepressant for 12 weeks could be considered comparable to a trial with standard antidepressant doses for 6 weeks. This staging model assumes that nonresponse to two agents of different classes is more difficult to treat than is nonresponse to two agents of the same class, and, indirectly, that the switch to an antidepressant within the same class is less effective than the switch to an antidepressant of a different class. Although this view has been supported by Poirier and Boyer18 (who showed that the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor [SNRI] venlafaxine was significantly more effective than the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor [SSRI] paroxetine in patients who had not responded to at least two trials of antidepressants [mostly SSRIs]), a recent study by Rush and colleagues19 showed no significant difference in outcome between venlafaxine or bupropion and the SSRI sertraline in patients who had not responded to the SSRI citalopram. In this staging method, there is also an implicit hierarchy of antidepressant treatments, with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) being considered superior to tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and SSRIs, and TCAs being considered more effective than are SSRIs. This hierarchy has not been supported by meta-analyses of antidepressant clinical trials, nor by a recent crossover trial of imipramine and sertraline.20,21 Finally, the role of augmentation or combination strategies is not considered in this staging method. For example, a depressive episode that has not responded to two antidepressant trials with SSRIs augmented with lithium, stimulants, and atypical antipsychotic agents could be considered less resistant than a depressive episode that has not responded to two antidepressants of different classes.

DEFINITION OF TREATMENT-RESISTANT DEPRESSION

The most common definition of TRD is that of inadequate response (i.e., failure to achieve remission) to at least one antidepressant trial of adequate dose and duration.7 This definition includes an operational classification of the degree of treatment resistance: (1) nonresponse (< 25% symptom reduction from baseline); (2) partial response (25% to 49% symptom reduction from baseline); and (3) response without remission (≥ 50% symptom reduction from baseline without achieving remission).7 One of the reasons for distinguishing between partial response and nonresponse is that a clinician’s treatment approach to partial responders differs from that used for nonresponders.22 Using such classification, a meta-analysis of clinical trials found that, among antidepressant-treated depressed patients, partial response occurs in 12% to 15% and nonresponse in 19% to 34%.7

MASSACHUSETTS GENERAL HOSPITAL STAGING METHOD TO CLASSIFY TREATMENT-RESISTANT DEPRESSION

Given the issues mentioned previously concerning Thase and Rush’s staging method, Fava and associates proposed a different staging method (Table 44-1), which would take into consideration both the number of failed trials and the intensity/optimization of each trial, but would not make assumptions regarding a hierarchy of antidepressant classes.23 This method generates a continuous variable that reflects the degree of resistance in depression, with higher scores indicating greater treatment resistance.23 A recent study tested this staging method against Thase and Rush’s method by having psychiatrists from two academic sites review charts and apply these two treatment-resistant staging scores to each patient. Logistical regression indicated that greater scores on the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) method, but not greater scores on the Thase and Rush method, predicted nonremission.24

Table 44-1 Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Staging Method to Classify Treatment-Resistant Depression

From Fava M: Diagnosis and definition of treatment-resistant depression, Biol Psychiatry 53:649-659, 2003. Copyright 2003, Elsevier.

PSEUDORESISTANCE

The term pseudoresistance has been used in reference to nonresponse to inadequate treatment (in terms of duration and/or dose of the antidepressant[s] used).25 Whether any patient with an inadequate response to antidepressant treatment has received adequate antidepressant treatment needs to be ascertained (i.e., “Did the patient receive antidepres sant treatment for at least 8 to 12 weeks? Were the doses prescribed in the therapeutic range? Did the patient take the medication as prescribed? Were multiple doses missed?”) These questions need to be addressed in order to rule out pseudoresistance.

Certain pharmacokinetic factors may also contribute to the phenomenon of pseudoresistance. Several studies have linked nonresponse to lower plasma/serum levels of TCAs.26,27 For example, the concomitant use of metabolic inducers (e.g., drugs that may increase the metabolism and elimination rate of co-administered agents) may be associated with a relative reduction in antidepressant blood levels, leading to an inadequate response. A similar problem may occur among patients who are rapid/fast metabolizers, as ultrarapid metabolism has been associated with worse response to standard doses of antidepressants.28 The problem with the newer antidepressants is that blood level–response relationships have not been well studied or established, nor has their role in TRD been adequately investigated. Therefore, it is hard for clinicians to know when someone is not responding to a specific antidepressant treatment because of pharmacokinetic factors. Nonresponse in the absence of any side effect should raise the possibility of a less than adequate antidepressant blood level, and a measurement of antidepressant blood level may be helpful and indicated in these circumstances.

Another aspect of pseudoresistance concerns a patient who is misdiagnosed as having a unipolar depressive disorder. A patient who has not had an adequate response to antidepressant treatment should undergo diagnostic reevaluation to ensure that his or her depression is truly a form of unipolar depressive disorder, and not a form of bipolar disorder or another psychiatric conditions (e.g., posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD] or vascular dementia). As Bowden’s review notes, a bipolar diagnosis can be suggested to a clinician by virtue of a family history of bipolar disorder, a history of spontaneous or antidepressant-induced episodes of mood elevation, a high frequency of depressive episodes, a greater percentage of time ill, and a relatively acute onset or offset of symptoms.29

PREDICTORS OF RESISTANCE TO A SINGLE ANTIDEPRESSANT TREATMENT

A number of clinical and sociodemographic variables have been studied in relationship to resistance to antidepressant therapy. The search for valid and robust predictors of resistance to a single antidepressant treatment has been frequently filled with inconsistent findings.30 This is partly due to the fact that many published studies of predictions were rather small, while large sample sizes are needed to establish with confidence the relationship between a given predictor and worse response to antidepressant treatment. In addition, it is not clear that predictors are independent of the type of treatment. For example, atypical depression, a subtype of MDD, has been associated with a worse response to treatment with TCAs, but not SSRIs or MAOIs.31–33

Other subtypes of depression, such as melancholia, have typically fared poorly in predicting poorer response to antidepressant treatment.30,33 Chronic forms of depression, such as index depressive episodes lasting 2 years or more or double depression (a major depressive episode superimposed on a dysthymic disorder), have been associated with worse outcome in some but not all studies.33–36 The depressive subtype with probably the most consistent prediction of poorer outcome is anxious depression.33,37

A commonly studied contributing factor to TRD is psychiatric co-morbidity. Substance abuse and even moderate consumption of alcohol have also been associated with worse response to antidepressant treatment.38 Other forms of psychiatric co-morbidity (such as MDD with co-morbid anxiety disorders [anxious depression]) have also been found to be associated with poorer response to antidepressant treatment.33 This is consistent with the observation that anxious depression (defined as depression with high ratings of anxiety symptoms) is less likely to respond to antidepressant treatment.33,37,39,40 The association between anxious depression and poorer response to antidepressant treatment may account for the fact that a recent study has shown that the concomitant use of anxiolytics/hypnotics was a significant predictor of treatment resistance in older adults with depression.41 One may argue that the negative effect of anxiety disorder’s co-morbidity is mostly related to specific forms of anxiety disorders (such as panic disorder or obsessive-compulsive disorder [OCD]). In fact, depressed patients with lifetime panic disorder showed a poor recovery in response to psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy in a large primary care study, and a lifetime burden of panic-agoraphobic spectrum symptoms predicts a poorer response to interpersonal psychotherapy.42,43

Co-morbid personality disorders have also been associated with worse outcome in some but not all studies.33,44–47 Similarly, although an initial study by Joyce and associates found that a model involving Cloninger’s temperament factors of Reward Dependence and Harm Avoidance scores, and their interaction, significantly predicted treatment response, subsequent studies that examined the relationship between such temperament types have failed to find a clinically significant relationship with resistance to treatment in depression.48–51 Such inconsistent findings have also affected studies concerning neuroticism, as neuroticism was found to be associated with poorer antidepressant response in earlier studies, but not more recent ones.30,52

Medical co-morbidity is often considered a potentially significant factor to the occurrence of TRD.53,54 One study of 671 elderly patients found that certain co-morbid medical disorders (such as arthritis and circulatory problems), but not other general medical conditions, were related to a worse outcome with respect to depressive symptoms.55 These findings would support the view that only specific forms of medical co-morbidity (e.g., diabetes and coronary artery disease) may have even higher chances of being associated with worse outcome.

Psychotic features in unipolar depression are associated with poorer treatment outcome following treatment with antidepressants alone.56–58 It is therefore essential that clinicians systematically assess nonresponding depressed patients for the presence of mood-congruent or mood-noncongruent psychotic features. When such features are detected, the addition of an antipsychotic agent appears to be warranted.58

Finally, failure to respond to multiple trials of antidepressants is often a significant predictor of worse response to antidepressant treatment.59

PREDICTORS OF RESISTANCE TO MULTIPLE ANTIDEPRESSANT TRIALS OR ELECTROCONVULSIVE THERAPY

One such study has shown that both a longer duration of the depressive episode and a relatively greater personality disorder co-morbidity were factors associated with poorer response to lithium augmentation.60 On the other hand, a relationship between personality disorder co-morbidity and poorer outcome in a treatment-resistant depressed sample was not apparent.52 Similarly, treatment-resistant patients did not differ in the degree of Axis I psychiatric co-morbidity from non–treatment-resistant depressed patients.61 The degree of medical co-morbidity was also not found to predict worse response to antidepressant treatment in the same sample of treatment-resistant depressed patients.62

HOW SHOULD CLINICIANS EVALUATE RESISTANCE IN DEPRESSION?

A basic requirement in the assessment of resistance in depression is the accuracy of the diagnosis. Misdiagnosis can be a relatively common problem in clinical practice, and it is often difficult to establish retrospectively whether the diagnosis of depression was accurate. One common approach to this problem is to complete a diagnostic reevaluation, ideally with a structured clinical interview, so that psychiatric co-morbidity is also systematically assessed. It is also important to assess the duration of the current trial and its interaction with the degree of response. As shown by Nierenberg and associates,63 minimal response after 4 weeks of antidepressant treatment predicts worse outcome at 8 weeks. These findings have challenged the utility of an 8- to 12-week trial in someone with no early signs of improvement. Another important step toward the assessment of resistance in depression concerns the level of drug treatment adherence. Clinicians need to ask their patients (whose depression has not responded to antidepressants) whether they actually took the antidepressant as prescribed (and in a consistent fashion). Finally, clinicians need to use reliable outcome measures to establish treatment resistance. While the use of clinician-rated instruments is preferred (see the following discussion), it is more common for clinicians to use global assessments, often combined with self-rated instruments, such as the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self-Rated (IDS-SR), the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) in its original and revised version, the Symptom Questionnaire (SQ), or the Harvard National Depression Screening Day Scale (HANDS).64–67

METHODOLOGICAL ISSUES IN TREATMENT-RESISTANT DEPRESSION RESEARCH

As mentioned earlier, when TRD is not determined prospectively, the inherent inaccuracy of retrospective assessments becomes a problem. For example, relapse may be misclassified as resistance. In a multicenter study by Fava and colleagues,68 some clinicians enrolled patients with relapse as if they were nonresponders. These misclassifications were identified through the use of the self-rated Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire, which documented the history of prior response to antidepressant treatment during the index episode.7

Another issue that affects TRD studies is the effect of new agents being used with SSRIs as active comparators. This type of design is confounded by the fact that the acceptability of a study using SSRIs as comparators is likely to be greater among patients who may have responded during previous episodes to SSRIs or had a transient positive response to SSRIs during the current episode (potentially enriching the sample with patients with a greater likelihood of response to SSRIs). An alternative approach to this problem is using an antidepressant drug of a different class as a comparator to the one used by patients during their index episode.

DIAGNOSTIC REASSESSMENT

Typically, the first step in the management of patients with TRD involves a diagnostic reassessment. Errors of omission in the initial diagnosis of psychiatric co-morbidity can have a negative impact on treatment outcome. One of the lessons learned from the NCR study is that most patients with MDD have co-morbid conditions that, in turn, can contribute to disease burden and could prevent a full response to treatment.4 For example, of patients who have MDD, 57.5% also have any anxiety disorder and about 9% have adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).69 While it would seem obvious that clinicians should treat patients’ co-morbid conditions to help achieve full remission, what is less obvious is how clinicians can identify and diagnose those co-morbid conditions that appear in routine practice and avoid errors of omission. Instruments such as the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) or the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) are routinely used in research settings, but are not used frequently in clinical settings.70,71 Perhaps it is not necessary for clinicians to conduct such extensive research evaluations on everyone at the outset of treatment, but instead, to provide a more systematic and comprehensive evaluation if a patient continues to feel depressed despite adequate treatment. Instruments such as the Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire (PDSQ) could be considered.72

PHARMACOLOGICAL OPTIONS FOR TREATMENT-RESISTANT DEPRESSION

High-Dose Antidepressants

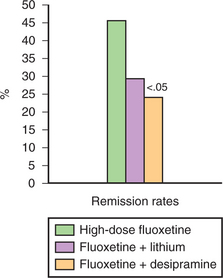

From a pharmacological standpoint, raising the dose of the antidepressant is a common approach to TRD. The dose of an antidepressant is usually raised within the recommended therapeutic dose range. In a survey of 412 psychiatrists from across the United States, respondents indicated their preferred strategies when a patient failed to respond to ≥ 8 weeks of an adequate dose of an SSRI.22 Interestingly, in the case of partial response, raising the dose was the first choice for 82% of the respondents, while raising the dose was endorsed by only 27% of the respondents in the case of nonresponse, with the remainder of the respondents selecting either switching a medication or an augmentation strategy. In two studies from our group, we identified 142 outpatients with MDD who were either partial responders or nonresponders to 8 weeks of treatment with fluoxetine 20 mg/day.73,74 These patients were then randomized to 4 weeks of double-blind treatment with high-dose fluoxetine (40 to 60 mg/day), fluoxetine plus lithium (300 to 600 mg/day), or fluoxetine plus desipramine (25 to 50 mg/day). When the data from these two studies were pooled, high-dose fluoxetine was significantly more effective than desipramine augmentation, and nonsignificantly more effective than lithium augmentation (Figure 44-1). These two studies provide evidence for the usefulness of raising the doses of antidepressants in the face of inadequate response to antidepressant treatment in depression.

Figure 44-1 High-dose fluoxetine compared with augmentation of fluoxetine with lithium or desipramine (n = 142).

(Data from Fava M, Rosenbaum JF, McGrath PJ, et al: Lithium and tricyclic augmentation of fluoxetine treatment for resistant major depression: a double-blind, controlled study, Am J Psychiatry 151:1372-1374, 1994; and Fava M, Alpert J, Nierenberg A, et al: Double-blind study of high-dose fluoxetine versus lithium or desipramine augmentation of fluoxetine in partial responders and nonresponders to fluoxetine, J Clin Psychopharmacol 22:379-387, 2002.)

Augmentation

Among the most widely studied augmentation agents is lithium (at > 600 mg/day), when added to TCAs, MAOIs, and SSRIs.75 Disadvantages of lithium augmentation include relatively low response rates in most recent studies, the risk of toxicity, and the need for blood level monitoring.74,76–78 Advantages of lithium augmentation are that the data supporting its efficacy are substantial. The pooled odds ratio (from nine studies) of response during lithium augmentation compared with placebo is 3.31 (95% confidence interval (CI), 1.46 to 7.53).75 Yet, even with these supporting data, less than 0.5% of depressed patients received lithium augmentation in a large pharmacoepidemiology study.79 On balance, lithium augmentation can be considered as a reasonable option, with the caveat that its efficacy may be rather limited with the newer generation of antidepressants.

Thyroid hormone (25 to 50 mcg/day) augmentation is another option that has received attention.80 L-triiodothyronine (T3) has been thought to be superior to thyroxine (T4).81 The disadvantages of thyroid augmentation are that all published controlled studies involved TCAs and only uncontrolled studies involved SSRIs.80,82–84 Of note, Iosifescu and colleagues found that among those who responded to thyroid augmentation, brain energy metabolism increased while those who did not respond had a decrease in brain energy metabolism (D. Iosifescu, personal communication). Among the four randomized double-blind studies, pooled effects were not significant (relative response, 1.53; 95% CI, 0.70 to 3.35; P = .29).80 STAR*D used an effectiveness design to compare lithium and thyroid augmentation after failure to reach remission with at least two prospective antidepressant trials.77 Thyroid was given openly, but assessments were done by either assessors blind to treatment or by self-report. Twenty-four percent of patients reached remission with thyroid, and there was a nonsignificant improvement greater than with lithium augmentation.

Buspirone, a 5-HT1A partial agonist (commonly prescribed at 10 to 30 mg bid) used early on in open augmentation trials of antidepressants, should augment SSRIs by blunting the negative feedback of increased synaptic serotonin effects on the presynaptic 5-HT1A receptor.85

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree