CHAPTER 54 Psychiatric Consultation to Medical and Surgical Patients

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

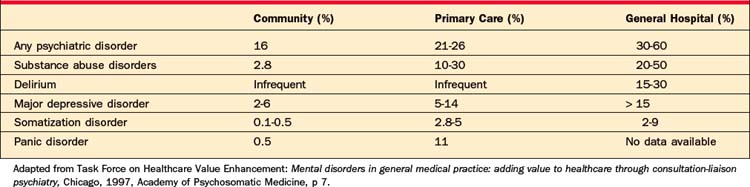

Compared to patients in the community and in primary care settings, patients in the general hospital have the highest rates of psychiatric disorders (Table 54-1).1 Despite this greater prevalence, rates of psychiatric consultation in this population are quite low and vary due to patient population, nature and severity of illness, length of stay, and idiosyncratic styles of referring physicians and consulting psychiatrists.2 At the Massachusetts General Hospital, the rate of psychiatric consultation is approximately 13% (Stern TA, personal communication, 2007). The most common stated reasons for psychiatric consultation are listed in Table 54-2. The diagnoses the consulting psychiatrist will usually make fall into the five categories listed in Table 54-3.

Table 54-2 Most Common Reasons for Psychiatric Consultation in the General Hospital

Table 54-3 Differential Diagnoses Made by Consulting Psychiatrists

PRINCIPLES OF PSYCHIATRIC EVALUATION OF MEDICAL AND SURGICAL PATIENTS

The key steps in the process of psychiatric consultation are listed in Table 54-4. Each is explained in detail below.

Table 54-4 Steps in the Process of Psychiatric Consultation

Review the Record

Busy consultants should resist the temptation to allow the referring physician’s synopsis of the patient’s medical history and hospital course to substitute for a thorough review of the hospital record. Often the written record contains invaluable data the referring physician may not even be aware of or pay attention to. For example, notes from nurses, nutritionists, and physical, occupational, and speech therapists frequently prove invaluable in assessing a patient’s affective, behavioral, and cognitive states. Of all the patient’s physicians, the psychiatric consultant may be the only physician to study these important entries. Ambulance “run” sheets and emergency department notes are also helpful. For example, knowing whether the patient initiated or cooperated with the process of getting to the hospital can be hugely useful in capacity evaluations and in assessments after suicide attempts. In most instances, previous records do not have to be reviewed as exhaustively, but a selected review of relevant notes (e.g., a previous psychiatric consultation note) may be helpful.

Interview the Patient

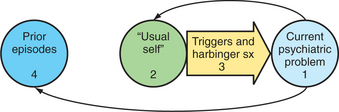

The psychiatric interview of a patient in the general hospital is identical in principle to that performed in most other venues. Areas of inquiry are identified; a diagnosis is pursued; and contributing factors from other aspects of the patient’s background, current circumstances, and personal characteristics are elicited. A longitudinal conceptualization of the problem is useful (Figure 54-1). Thorough description of the presenting problem should be followed by an appraisal of the patient’s psychological baseline. The patient should be asked when she last felt like her “usual self” rather than when she last felt “normal” or “good,” since some patients do not view themselves in these terms. Descriptions of that time should be provided and detailed questions should be asked (e.g., “How did you spend your time then?” and “Would I notice a difference about you if I met you then?”). The patient should be invited to speculate on how her “usual self” might cope differently with her medical situation. If the answer is “the same,” this provides an opportunity to explore characterological vulnerabilities. If not, this becomes an opportunity to look at intervening psychopathology or at demoralization. Either way, most patients appreciate the psychiatrist’s interest in matters other than their symptoms. After this baseline is obtained, triggers or harbinger symptoms of the presenting problem can be identified. Last, since most psychopathology is episodic, a history of similar problems in the past can be elicited. Many patients cannot be interviewed in such a fashion, but the history can still be organized this way after the interview.

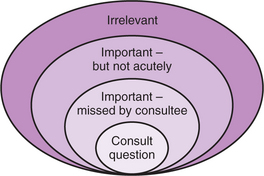

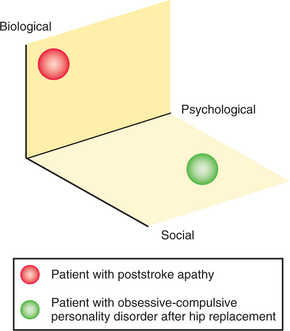

A schema for understanding the scope of the consulting psychiatrist’s interview is presented in Figure 54-2. Although the consultee’s question must be kept in mind throughout the interview, consultees often misidentify psychopathology and thus the consultation question should be taken only as a suggestion.3–5 At the same time, the psychiatrist should not function as the local “biopsychosocial expert,” for whom just about anything in the patient’s life is worthy of attention.6 Rather, the consultant should generally situate himself or herself just outside the border of the “missed by consultee” circle and just inside the “important–but not acutely” circle. Keeping the interview in this area requires clinical judgment beyond simply “being biopsychosocial.” For example, a patient with acute apathy after a stroke has very different needs from the patient with a life-long obsessive-compulsive personality disorder who is driving his family and the hospital staff to distraction after a hip replacement (Figure 54-3).

Conduct a Mental Status Examination

There are no unexaminable patients in consultation psychiatry. Even the profoundly delirious patient who cannot maintain alertness can have his or her level of arousal assessed. Noncognitive aspects of the mental status examination (MSE) are the same as in routine psychiatric practice and are discussed in Chapter 2. This section focuses on the principles of neuropsychological assessment and screening. We use the term screening to distinguish what the physician does at the patient’s bedside from testing, a more rigorous and quantitative task usually performed by a neuropsychologist.

Neuropsychological assessment of the hospitalized patient begins not with specific screens, but with the interview itself.7 Acutely ill patients may be unmotivated to engage in a cognitive screening battery. Since motivation plays a key role in task performance, the consultation psychiatrist must be vigilant to the patient’s spontaneous processes, and subtly, yet purposefully, evoke them during the interview. For example, the patient who knows the up-to-the-minute details of her hospital course yet recalls none of the three items on the Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)8 does not have severe anterograde amnesia.

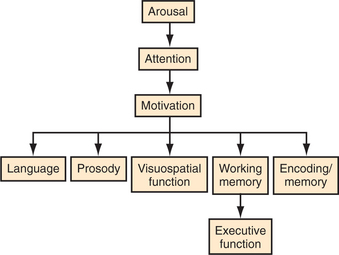

A fundamental principle of neuropsychological assessment is that mental functions are hierarchical. That is, some functions cannot be assessed validly if the faculties “above” them are disrupted. The broadest distinction in this ranking is that of state-dependent versus channel-dependent functions.9 State-dependent functions include arousal, attention, and motivation. Subordinate to these are channel-dependent functions, comprising language, prosody, visuospatial function, executive function, praxis, comportment, and the various forms of memory (Figure 54-4). We now briefly review the state-dependent functions, and those channel-dependent functions that are of particular value to the consulting psychiatrist.10,11 Table 54-5 gives a summary.

Table 54-5 Examples of Screening Tasks for Selected Cognitive Domains

| Cognitive Domain | Screening Task |

|---|---|

| Arousal | |

| Attention | |

| Motivation | |

| Language | |

| Memory | |

| Executive function |

Arousal

Unless the patient is clearly alert, the examination begins with assessment of arousal. The Glasgow Coma Scale score may be used for profoundly impaired patients.12 The terms lethargic, somnolent, and obtunded should be avoided since most physicians use them imprecisely. Description of the patient’s level of arousal that is based on the following three parameters is more useful:

Attention

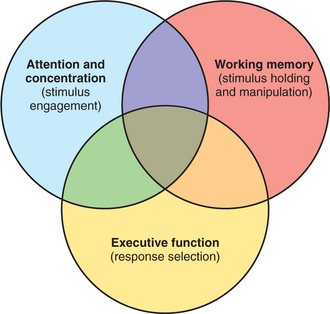

Attention and concentration refer to the abilities to engage appropriate stimuli without distraction by sensory inputs. Working memory refers to the ability not only to hold selected information, but to manipulate it.13 Executive function involves response selection and guides the “work” of working memory. These three cognitive functions share dorsolateral-prefrontal–subcortical circuitry. The complex overlap among them is simplified in Figure 54-5. Assessment of attention begins with simple observation of the patient during the interview while watching for distraction by extraneous internal or external stimuli. Forward digit span is the gold standard for quantitatively testing attention at the bedside. Backward digit span or backward recitation of over-learned information (e.g., days of the week or months of the year) uses information that is less determined by education or culture than is a spelling or a mathematical task. The cognitive work being done on the information is simple, and, though it invokes working memory, we see it as occupying the overlap area in Figure 54-5.

Language

Fluency, comprehension, repetition, and naming are the basic components of language testing.14 The intactness of the first two is usually apparent from the interview alone. Fluency should not be mistaken for comprehensibility (e.g., patients with Wernicke’s aphasia speak fluently, but nonsensically). The comprehension of the noncommunicative or minimally communicative patient can be discerned by asking absurd questions (e.g., “Do helicopters in Panama eat their young?” [Cassem NH, personal communication, 2000]). Naming should include components of objects (e.g., the face of a watch or the cap of a pen), as well as whole objects (e.g., a watch or a pen).

Memory

When assessing memory at the bedside, one needs to keep in mind the type, timing, and component of it that is being scrutinized. Declarative or explicit memory, which includes both episodic (experiential) and semantic (factual) memory, is the type usually screened at the patient’s bedside.15 Recent memory operates on a scale of minutes to days, remote memory on a scale of days to years.16 Problems of encoding, consolidation, and retrieval (Figure 54-6) will cause errors of recall (e.g., the three items on the MMSE).14

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree