CHAPTER 57 HIV and AIDS

OVERVIEW

Once a dread illness that portended certain death after months or years of inexorable decline, infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has become a chronic, treatable illness. Well into the third decade of the epidemic, more than 20 medications are currently available that curtail progression to the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)—the end stage of infection that, during the early years of the pandemic, was inevitable for nearly all patients. The advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in 1995 reduced AIDS incidence and mortality rates and increased the life expectancy of patients with HIV.1

For the reasons listed in Table 57-1, the general psychiatrist—regardless of venue and type of practice—will be called on to evaluate and to treat a fair share of patients with HIV infection. This chapter reviews the epidemiology, basic biology, classification, and diagnosis of HIV infection; a general approach to psychiatric care of HIV-infected patients; psychiatric and neurological disorders common in this population, and their treatments; and special clinical problems encountered in HIV psychiatry.

Table 57-1 Why Are the Principles of HIV Psychiatry Important?

• Many patients with HIV infection have psychiatric problems, both antecedent and consequent to contracting the virus |

HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

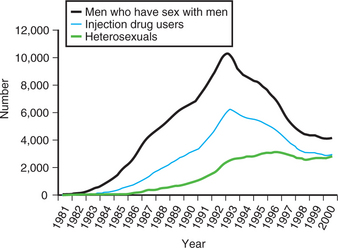

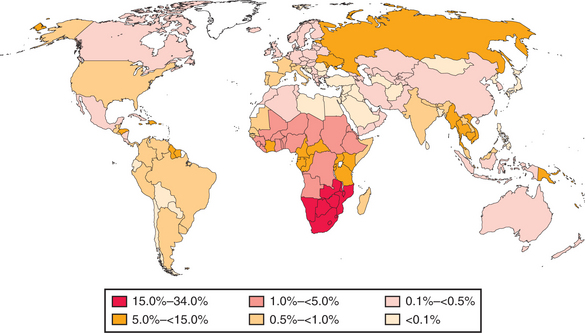

At the end of 2005, nearly 40 million people worldwide were living with HIV infection.2 While the prevalence rate of infection has plateaued, the absolute number of people with HIV continues to rise (Figure 57-1). Africa, especially the sub-Saharan region, remains the epicenter of the pandemic, followed by the Caribbean (Figure 57-2).

Figure 57-1 Global HIV prevalence, 1990–2005.

(Adapted from UNAIDS: 2006 report on the global AIDS epidemic, Geneva, 2006, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.)

Figure 57-2 Global HIV prevalence, 2005.

(Adapted from UNAIDS: 2006 report on the global AIDS epidemic, Geneva, 2006, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.)

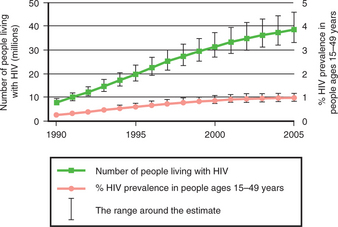

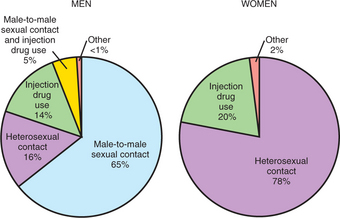

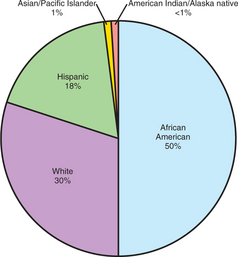

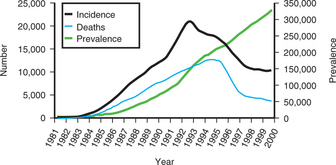

In the United States, at the end of 2005, more than 1 million people were living with HIV infection.2 Approximately 40,000 new infections occur yearly.3 Of these, in 2004, the largest proportion occurred in men who have sex with men (MSM); 27% occurred in women, mostly through heterosexual contact; and half occurred among African Americans (Figures 57-3 and 57-4).4 New cases of and deaths due to AIDS declined sharply in 1996, owing largely to HAART (Figure 57-5).5 The sharpest declines were in the MSM and injection-drug-using populations (Figure 57-6).5 Between 2000 and 2004, however, while AIDS deaths decreased by 8%, new AIDS cases increased by the same amount.6

Figure 57-3 New HIV diagnoses in the United States, 2004, by mode of transmission.

(Adapted from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: A glance at the HIV/AIDS epidemic, April 2006. Available at www.cdc.gov/hiv.)

Figure 57-4 New HIV diagnoses in the United States, 2004, by race.

(Adapted from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: A glance at the HIV/AIDS epidemic, April 2006. Available at www.cdc.gov/hiv.)

Figure 57-5 AIDS incidence, prevalence, and deaths in the United States, 1981–2000.

(Adapted from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: HIV and AIDS—United States, 1981–2000, MMWR 50:430-434, 2001.)

BASIC BIOLOGY

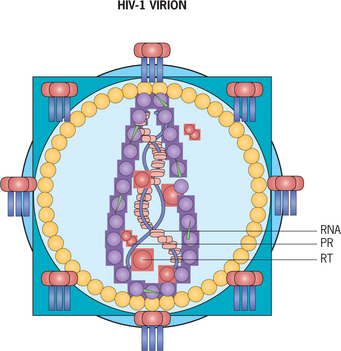

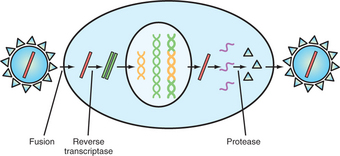

HIV (Figure 57-7) is a retrovirus—a virus containing ribonucleic acid and the enzyme, reverse transcriptase, for replication—that affects the immune system and the central nervous system (CNS), gaining entry to cells (e.g., T-lymphocytes, monocytes, and macrophages) that express the CD4 receptor on their membranes. The life cycle of the virus once inside an infected cell is depicted in Figure 57-8. All of the currently available antiretroviral medications target the three key steps and enzymes in this process: fusion of the virus with the host cell membrane; reverse transcriptase; and protease.

Figure 57-7 Human immunodeficiency virus. PR, Protease; RNA, ribonucleic acid; RT, reverse transcriptase.

(Modified from Cohen J, Powderly WG, editors: Infectious diseases, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2004, Elsevier, p 1252.)

Figure 57-8 Life cycle of HIV.

(Adapted from Cohen J, Powderly WG, editors: Infectious diseases, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2004, Elsevier, p. 1254.)

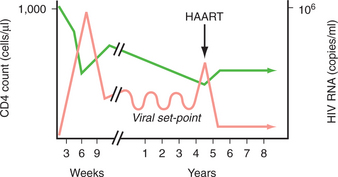

During the first weeks after infection, the population of CD4+ T-lymphocytes (i.e., the CD4 count) decreases as the amount of virus in the blood (i.e., the viral load) increases (Figure 57-9). Following a weak and short-lived rebound, the CD4 count steadily declines. At the same time, the viral load oscillates around a “set-point” until ultimately viral replication intensifies and peripheral viremia surges. Administration of HAART, when effective, halts this process. Opportunistic infections (OIs), neoplasms, and neuropsychiatric conditions occur with increasing frequency as the immune deficiency worsens; prophylaxis for certain OIs (e.g., Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia and toxoplasmosis) is instituted during the course of infection according to the CD4 count.

CLASSIFICATION AND DIAGNOSIS

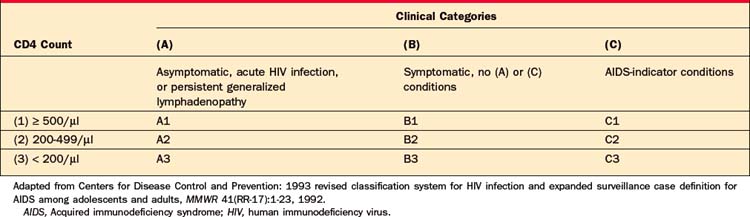

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),7 AIDS is defined by a CD4 count below 200 cells/μl (or less than 14% of total lymphocytes) or the presence of an AIDS-defining condition (Table 57-2). This 1993 revised classification established nine possible categories of illness (Table 57-3). The introduction of HAART has diminished the clinical utility of this taxonomy.

Table 57-2 AIDS-Defining Conditions

| Candidiasis Cervical cancer, invasive Coccidioidomycosis Cryptococcosis Cryptosporidiosis Cytomegalovirus disease or retinitis Herpes simplex virus infection Histoplasmosis HIV-related encephalopathy HIV-related wasting syndrome Isosporiasis Kaposi’s sarcoma Lymphoma (Burkitt’s, immunoblastic, or primary CNS) Mycobacterial infection (M. avium complex, M. kansasii, M. tuberculosis, or other species) Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia Pneumonia, recurrent Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy Salmonella septicemia, recurrent Toxoplasmosis, cerebral |

AIDS, Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; CNS, central nervous system; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Adapted from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults, MMWR 41(RR-17):1-23, 1992.

Infection with HIV is usually diagnosed in two steps. The initial test is an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). A positive result on this test is then confirmed by a Western blot test. Screening used to be recommended based on risk factors for infection, but the CDC is now recommending that HIV testing be done as part of routine clinical care for all patients.8 One compelling reason for this change is the high percentage (approximately one-quarter) of HIV-infected people in this country who do not know they are infected.

GENERAL APPROACH TO PSYCHIATRIC CARE

Psychiatric symptoms in a patient with HIV infection may be primary or secondary (Tables 57-4 and 57-5); the CD4 count is useful in making this differential diagnosis. A CD4 count greater than 500 cells/μl suggests a primary psychiatric cause, whereas a CD4 count less than 200 cells/μl, and a fortiori less than 50 cells/μl, suggests the psychiatric problem is secondary to the effects of immune compromise. For example, a patient who has just been told that he is HIV-positive but whose CD4 count is still normal and whose viral load is low may become depressed as part of an adjustment disorder (a primary psychiatric problem). However, 10 years later, when he again has depressed mood and his CD4 count is 100 cells/μl, he may very likely have an OI or a neoplasm affecting his CNS and causing depression (a secondary psychiatric problem).

Table 57-4 Differential Diagnosis of Psychiatric Symptoms in the HIV-Infected Patient

| Primary |

| Psychiatric disorders |

| Secondary |

HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus.

Adapted from Querques J, Worth JL: HIV infection and AIDS. In Stern TA, Herman JB, editors: Massachusetts General Hospital psychiatry update and board preparation, ed 2, New York, 2004, McGraw-Hill, p. 205.

Table 57-5 Neuropsychiatric Side Effects of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy and Other Medications Used in the HIV-Infected Patient

| Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NRTIs) | |

| Abacavir | Headache |

| Didanosine | Insomnia, mania, peripheral neuropathy |

| Lamivudine | Similar to zidovudine |

| Stavudine | Mania, peripheral neuropathy |

| Tenofovir* | Asthenia, anorexia |

| Zalcitabine | Peripheral neuropathy |

| Zidovudine | Headache, insomnia, mania, restlessness, agitation, delirium, depression, irritability, somnolence |

| Nonnucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NNRTIs) | |

| Delavirdine | Headache |

| Efavirenz† | Agitation, insomnia, euphoria, depression, somnolence, abnormal dreams, confusion, impaired concentration, amnesia, depersonalization, hallucinations, false-positive cannabinoid test |

| Nevirapine | Headache |

| Protease Inhibitors (PIs) | |

| Amprenavir | Headache |

| Indinavir | Headache, asthenia, insomnia, blurred vision, dizziness |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | Headache, asthenia, insomnia |

| Nelfinavir | Headache, asthenia |

| Ritonavir | Asthenia, circumoral and peripheral paresthesias, altered taste |

| Saquinavir | Headache |

| Other Antivirals | |

| Acyclovir | Headache, agitation, insomnia, tearfulness, confusion, hyperesthesia, hyperacusis, depersonalization, hallucinations |

| Ganciclovir | Agitation, mania, psychosis, irritability, delirium |

| Antibacterials | |

| Cotrimoxazole | Headache, insomnia, depression, anorexia, apathy |

| Dapsone | Agitation, insomnia, mania, hallucinations |

| Isoniazid | Agitation, depression, hallucinations, paranoia, impaired memory |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | Headache, insomnia, depression, anorexia, apathy, delirium, neuritis |

| Antiparasitics | |

| Metronidazole | Agitation, depression, delirium, seizures (with IV administration) |

| Pentamidine | Confusion, delirium, hallucinations |

| Thiabendazole | Hallucinations, olfactory disturbances |

| Antifungals | |

| Amphotericin B | Headache, delirium, agitation, anorexia, lethargy, diplopia, peripheral neuropathy |

| Flucytosine | Headache, delirium, cognitive impairment |

| Ketoconazole | Headache, dizziness, photosensitivity |

| Others | |

| Cytosine arabinoside | Delirium, cerebellar signs |

| Steroids | Euphoria, mania, depression, psychosis, confusion |

HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus.

* Nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NtRTI), related to NRTIs.

† Neuropsychiatric side effects related to plasma level (Gutierrez F, Navarro A, Padilla S, et al: Prediction of neuropsychiatric adverse events associated with long-term efavirenz therapy, using plasma drug level monitoring, Clin Infect Dis 41:1648-1653, 2005).

Adapted from Querques J, Worth JL: HIV infection and AIDS. In Stern TA, Herman JB, editors: Massachusetts General Hospital psychiatry update and board preparation, ed 2, New York, 2004, McGraw-Hill, p. 206.

Optimum treatment of HIV infection and related conditions is essential for effective psychiatric care. Preferably the patient will be on HAART with agents that penetrate the blood-brain barrier so that the CNS effects of the virus are minimized. When this is not possible (e.g., because of viral resistance patterns), the patient still stands to benefit neuropsychiatrically from HAART because viral suppression and immune restoration will enhance psychiatric treatment. Close collaboration between the psychiatrist and the physician providing the HIV care (usually a specialist in infectious diseases) is crucial.

PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS

Substance Use Disorders

Substance use disorders are well represented among HIV-infected patients. The 12-month prevalence of drug dependence in the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study (HCSUS)—a study of a nationally representative sample of nearly 3,000 HIV-infected adults in the United States—was 12.5%.9 Between 40% and 45% of injection-drug users in the United States are HIV-positive, and 25% to 30% of non–injection-drug users have the infection.10 Substance use disorders affect the transmission, course, and treatment of HIV infection in numerous ways (Table 57-6).

Table 57-6 Adverse Effects of Substance Use in the Context of HIV Infection

HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus.

So-called “club drugs”—methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, “ecstasy”), gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB, “liquid ecstasy”), and ketamine (“special K”)—and other related compounds (e.g., methamphetamine [speed, crystal meth]) have become increasingly popular drugs of abuse, in part because of their effects on social disinhibition and sexual enhancement. As a result, they can pave the way to HIV transmission. By virtue of pharmacokinetic interactions with the cytochrome P-450 system, the co-administration of “club drugs” with antiretroviral medications can have harmful consequences. Adverse effects of MDMA and GHB, thought to be due to interactions with protease inhibitors, have been reported.11,12 Protease inhibitors, especially ritonavir, may inhibit the metabolism of amphetamines and ketamine.11

Many stressors during the course of HIV infection threaten both the establishment and the maintenance of sobriety in patients with substance use disorders (Table 57-7). Fortunately, several medications are now available to treat these conditions; unfortunately, some of them are known to have interactions with antiretroviral medications. Interactions between methadone and various antiretroviral agents are presented in Table 57-8. While these interactions may produce measurable changes in methadone plasma levels, such alterations do not consistently result in clinical manifestations.13 Withdrawal phenomena have been observed with efavirenz, nevirapine, and nelfinavir.10,14

Table 57-7 Stressors during HIV Infection

| Diagnosis and Treatment |

| Experience of Symptoms |

| Psychosocial Consequences |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|