CHAPTER 91 Coping with the Rigors of Psychiatric Practice*

EPIDEMIOLOGY

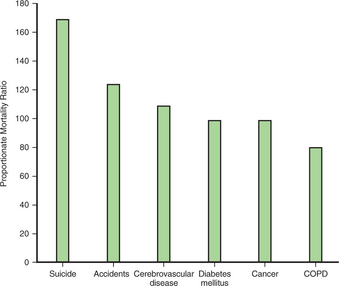

Despite their academic, vocational, and societal success, physicians are immune to neither disease nor suffering. In fact, one can argue that physicians are more likely to experience emotional distress, given the nature of their work; studies that have identified high rates of suicide among physicians support this idea. While physicians, as a group, have lower mortality rates from several diseases (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and liver disease), they have a higher rate of suicide than do other professionals and members of the general population1 (Figure 91-1); for male physicians, the relative risk ranges from 1.1 to 3.4, and for female physicians, the relative risk ranges from 2.5 to 5.7.2 In the general population, the suicide rate is four times higher for men than it is for women; in physicians, the rate of suicide for women is equal to that of men.3 Up to 12% of physicians report an increased use of substances during residency4; psychiatrists have particularly high rates of substance abuse compared to those in other medical specialties.

ETIOLOGIES FOR STRESS AND BURNOUT

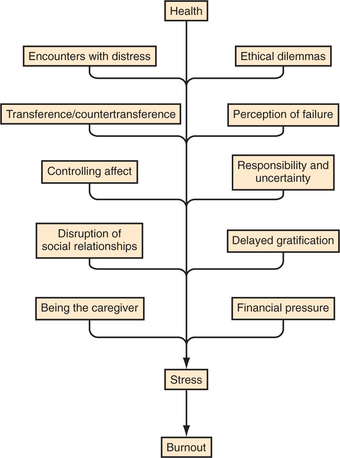

The practice of medicine in today’s society is both challenging and rewarding; however, it is also stressful and not without the potential for burnout. Several aspects of psychiatric practice leave the psychiatrist especially vulnerable to stress and, ultimately, to burnout (Figure 91-2).

Controlling Affect

Despite the intensely emotional nature of psychiatric work, psychiatrists must consistently control their affect to do their jobs well. When patients are overwhelmed by sadness, despair, anger, or frustration, psychiatrists must keep their own reactions in check, sometimes bottled deep within. While this control of affect is necessary for the practice of psychiatry, it can ultimately lead to the denial of emotions. If one denies the existence of affect (even after the patient has left the office), it can lead to increased stress and to vulnerability to burnout. Instead, informal debriefings with colleagues, or formal supervision, may encourage the necessary expression of what is controlled during patient sessions.

SPECIAL SITUATIONS IN PSYCHIATRY

Coping with Patient Suicide

A Profound and Enduring Effect

Half of all psychiatrists have had one (or more) of their patients commit suicide5,6; approximately one-third of those psychiatrists experienced such a loss while they were still in residency training.5 Furthermore, one-quarter of psychiatrists who had experienced patient suicide stated that it had “a profound and enduring effect” on them throughout their careers.5 While the practice of most medical specialties entails dealing with death, suicide in the practice of psychiatry takes on additional meaning. Since one of the primary tools in psychiatry is the individual, when the treatment fails, it can feel as if the treater has failed. Furthermore, while death from cancer can be seen as inevitable, death from suicide can be viewed as a choice.7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree