Absence Seizures

Selim R. Benbadis

Samuel F. Berkovic

Absence seizures are the most extensively studied type of epileptic seizure. The remarkable association of clinical absences with generalized spike-wave discharges was recognized soon after the advent of electroencephalography (1, 2, 3). The relatively stereotyped clinical manifestations, along with frequent occurrence, ease of precipitation in the laboratory, and obvious and consistent electroencephalographic (EEG) expression, made absences the paradigm for detailed electroclinical correlations (4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9).

As discussed in Chapter 19, the terms “absence seizure” and “dialeptic seizure” have been proposed in a semiologic classification based on signs and symptoms only, regardless of EEG findings. In contrast to a purely symptomatologic approach, this chapter discusses absence seizures as defined electroclinically by the International Classification of Epileptic Seizures.

CLINICAL FEATURES

The International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) classification of epileptic seizures recognizes two major types of absences: typical and atypical (10). Typical absences are characteristic of the idiopathic (“primary”) generalized epilepsies (11,12), especially childhood and juvenile absence epilepsy and, less frequently, juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Atypical absences, which have been less intensively studied, are seen in patients with symptomatic or cryptogenic generalized epilepsies, particularly Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (13, 14, 15).

Typical Absences

The characteristic features of typical absences allowed their identification as early as 1705, when Poupart wrote the first description. In the 20th century, Sauer introduced the term “pyknolepsy,” which Adie subsequently used in characterizing the syndrome of childhood absence epilepsy (16,17). Although typical absences generally manifest in childhood, persistence into adult life may occur (18,19), and occasionally they can present de novo in adulthood (20). Typical absences usually last about 10 seconds (5,7,21). In the study by Penry and associates (7) of 374 absence seizures in 48 patients, the mean duration was 9 seconds (range, 1 to 45 seconds). Postictal confusion is either absent or very brief, lasting 2 or 3 seconds. Video-EEG monitoring has allowed a moment-by-moment analysis of the attacks.

The ILAE classification recognizes subtypes of typical absence seizures (10), and mixed forms with various combinations can be seen.

Absence with impaired consciousness. Ongoing activities cease abruptly, and the patient is motionless with a fixed blank stare and loss of contact; the eyes may roll upward briefly. The attack ends suddenly, with the patient usually unaware of the episode, although the passage of time may be deduced. After the attack, activities resume.

Absence with (mild) clonic components. Mild clonic activity involves the eyelids, corners of the mouth, and sometimes the upper extremities. These clonic jerks, usually at 3 per second, can be subtle.

Absence with atonic components. Sudden hypotonia may cause the head or trunk to slump forward and objects to drop from the hand. Falling is rare.

Absence with tonic components. Increased tone may affect the flexors or extensors and may be symmetrical or asymmetrical. A standing patient may be propelled backward, and an asymmetrical increase in tone may turn the head or trunk to one side. Tonic features are always relatively minor and should not lead to confusion with the movements of generalized tonic seizures.

Absence with automatisms. When the absence attack is relatively prolonged, automatisms may resemble those of complex partial seizures. Automatisms evolve in a craniocaudal fashion, with elevation of the eyelids, licking and swallowing, and, finally, fiddling and scratching movements of the hands (8,9).

Absence with autonomic phenomenon. Perioral pallor, pupillary dilation, flushing, tachycardia, piloerection, salivation, and incontinence may occur.

The frequency of these various features depends on how carefully they are looked for and the referral base from which cases are drawn. On the basis of ordinary history taking, simple absences and absences with mild clonic phenomena are by far the most common, followed by absences with automatisms and decreased postural tone. Studies using videotapes increase the frequency of the less commonly identified types and mixed forms (7). The categorization of typical absences into the above subtypes, although useful descriptively, probably has no clinical or neurobiologic significance. Many authors now refer only to simple absences and complex absences, the latter describing attacks with any combination of clonic, atonic, tonic, automatic, or autonomic features (22,23).

In the electroencephalography laboratory, typical absences are precipitated by hyperventilation in virtually all untreated patients and by photic stimulation in approximately 15% of individuals. The level of hypocapnia that induces absence seizures appears to vary among individuals (24). In everyday life, absences often occur with tiredness or boredom and are generally suppressed by attention, although demanding tasks and, in some patients, specific mental activities, such as calculation, may precipitate absences (25). Overbreathing during physical exercise decreases the frequency of absences (26).

Atypical Absences

Atypical absences have not been studied as thoroughly as typical absences and have been distinguished from the latter mainly by EEG criteria (5,21). The clinical features of atypical absences have resisted easy recognition because the patients are often mentally retarded and exhibit multiple other seizure types, both features being typical of symptomatic or cryptogenic generalized epilepsies (see Chapter 22). In addition, onset and offset are not as crisply delineated as are those of typical absences, partly because polypharmacy in intellectually disabled patients makes detection of altered awareness difficult. Careful analysis of videotaped seizures, however, often shows a change in behavior when the ictal discharge terminates (21).

Atypical absences average about 5 to 10 seconds in length (5,21,27), although they can be prolonged to the extent of absence status. Minor myoclonic, tonic, atonic, and autonomic features, as well as automatisms, may accompany the altered awareness. Tonic seizures, characterized by rhythmic fast activity, frequently occur, and the clinical and EEG features merge into those of the atypical absence (21,23). Unlike typical absences, however, atypical absences are usually not precipitated by hyperventilation or photic stimulation (21,28).

Other Types of Absences

The relationship of absence and myoclonus is complex, and the nomenclature in the literature is confusing. Rhythmic jerking of the eyelids and facial muscles is common in typical absences, but more widespread myoclonus as part of absence seizures is rare. In some patients, however, discrete myoclonic seizures involving the extremities (without impairment of consciousness) occur independently of absences. In principle, the distinction between absences with myoclonus and independent absence with myoclonic seizures is obvious, being based on impaired consciousness with myoclonic movements. In practice, however, this distinction can be ill defined in some patients and may require video-EEG monitoring to establish.

Tassinari and colleagues (29,30) described the myoclonic absence. Not specifically identified in the ILAE classification, this seizure involves 10 to 60 seconds of rhythmic jerking of the shoulders, arms, and legs, with tonic contraction around the shoulders. It has a poor prognosis and appears to be specific to the syndrome of epilepsy with myoclonic absences (see causes). The myoclonic absence cannot be confused clinically with true absence because of its obvious convulsive features; the name derives from an association with typical 3-Hz spike-and-wave discharges.

At the onset of an attack, some patients with absences and photosensitivity have jerking of the eyelids with upward eye deviation. Some experts regard these seizures as a special type known as eyelid myoclonia with absences (19,31, 32, 33). Others believe that the so-called eyelid myoclonia represents voluntary (or subconscious) eye blinking that precipitated photosensitive absences (34, 35, 36). Characteristically, voluntary eye closure is followed by slow upward eye movement and rapid fluttering of the eyelids. Some patients continue to show eye blinking, without impaired consciousness, when the epileptiform discharges have been suppressed by medication. Thus, continued blinking must not be uncritically accepted as evidence of uncontrolled absences. Whether the clinical features and natural history of these patients warrant designation as a separate subgroup remains unproved. Similarly, the proposal to designate perioral myoclonia with absences as a distinct group requires further study (37).

Delgado-Escueta and associates (38) used the terms “myoclonus absence,” “myoclonic absence with 4- to 6-Hz multispike-and-wave complexes,” and “juvenile absence with 8- to 12-Hz rhythms” to denote other allegedly distinct types of absence. Although attacks resembling absences with unusual electroclinical features undoubtedly occur, we find this nomenclature unhelpful and unsubstantiated by published data.

ELECTROENCEPHALOGRAPHIC FEATURES

The EEG signature of an absence attack is a bilaterally synchronous spike-and-wave discharge at 2.5 to 4.0 Hz. So strong is the association of clinical absences with generalized spike-and-wave discharge that it is probably inappropriate to regard staring spells with any other type of epileptic discharge as absences. Some electroclinical observations (see other electroencephalographic patterns ) suggest that other types of discharges may accompany clinical absences, but the classification of these events remains controversial. Because any epileptic spike is typically followed by a slow wave, a useful rule of thumb is to reserve the term spike-wave complexes for repetitive discharges of 3 or more seconds (41).

Typical Absences

Ictal Discharges

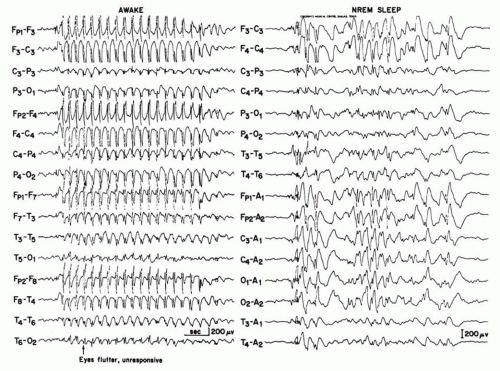

Typical absences show the classic 3-Hz spike-wave discharges (Fig. 19.1). The discharge begins suddenly without any preictal EEG disturbance. The frequency is usually about 3 to 4 Hz at onset and slows to 2.5 to 3.0 Hz toward the end of the discharge. A characteristic electrical field shows maximum negativity symmetrically at F7/F8 or F3/F4. A single spike is followed by a single wave (“dart and dome”); however, during sleep or in older patients, a double spike or, more rarely, multiple spikes may develop. Toward the end of the discharge, not only does the frequency decrease slightly, but the spikes may also become less apparent and drop out. The discharges are characteristically provoked by hyperventilation. Photic stimulation precipitates absence seizures in approximately 15% of patients (4,5,22,42, 43, 44, 45, 46).

Interictal Electroencephalography

Brief generalized 3-Hz spike-wave discharges occur without obvious clinical change. The distinction between interictal and ictal discharges in patients with typical absences is blurred and depends on the sophistication of testing. The morphology of the discharges does not differ, but the longer the discharge, the more likely it will have subtle or obvious clinical accompaniments. A generally accepted observation is that discharges lasting longer than 3 seconds can be noticed in everyday life by an attentive observer. Continuous response tasks show decreased performance during even briefer discharges and sometimes even slightly before the discharge. The background activity is normal, except for intermittent rhythmic posterior delta activity seen in some children.

During light sleep, the discharges increase in frequency and irregularity, and may develop into multiple spike discharges (Fig. 19.1). In stages III and IV of sleep, the number of spikes rises again, and the waves become longer and more distorted. The basic morphology during rapid eye movement sleep is similar to that during resting wakefulness. Polyspikes during sleep appear to be associated with a less favorable prognosis (47). This would make sense, because such cases would move closer toward the symptomatic

generalized epilepsy on the neurobiologic continuum described later in Figure 19.4.

generalized epilepsy on the neurobiologic continuum described later in Figure 19.4.

The discharges in simple absences are characteristically bilateral and symmetrical, but varying degrees of asymmetry and occasional brief unilateral discharges can be present. In such electroencephalograms, the asymmetries typically change from side to side, and on evaluation of the whole record, the generalized process becomes clear. Exceptionally, persistently unilateral discharges may occur. Such asymmetries should not lead to an erroneous diagnosis of partial epilepsy (48,49).

Atypical Absences

Ictal Discharges

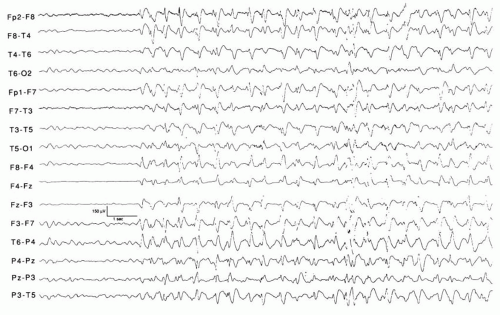

Generalized slow spike-wave discharges are usually far less regular (monomorphic) in morphology, lower in amplitude, and have broader and blunter spikes than those seen in typical absences (Fig. 19.2). The frequency is approximately 1.5 Hz (<2.5 Hz).

The discharges are distributed similarly to those of typical absences, but are more often asymmetrical and usually less perfectly monomorphic (i.e., more irregular). The asymmetry may correlate with focal neurologic signs or radiologic deficits on the affected side.

Interictal Electroencephalography

Brief bursts of slow spike and wave are superimposed on a diffusely slow background and focal or multifocal spikes. This combination of findings is characteristic of symptomatic or cryptogenic generalized epilepsies (see Chapter 22). The discharges are activated in sleep and interspersed with brief runs of generalized rapid spikes, with or without clinical tonic seizures (1,4,5,15,42,43,50,51).

Other Electroencephalographic Patterns

A number of other EEG patterns are associated with staring spells, but they are not clearly associated with absence seizures.

Generalized Rhythmic Delta Activity

Lee and Kirby (52) described seven children who experienced brief periods of loss of awareness associated with generalized high-amplitude rhythmic delta activity, without a spike component. Nearly all electroclinical observations were made during hyperventilation. The authors characterized these events as absences because of the consistent clinical features and the response to antiabsence medication. Our view, and that of others (28,53,54), is that such attacks represent hyperventilation-induced nonepileptic spells.

Low-Voltage Fast Rhythms

Gastaut and Broughton (5) described patterns of diffuse flattening, low-voltage fast activity at about 20 Hz, and rhythmic 10-Hz sharp waves associated with atypical absences, in addition to the classic slow spike-and-wave discharge. These patterns also typically accompany tonic seizures in patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. It is therefore arguable whether staring spells associated with these faster EEG rhythms, and often with some increase in axial tone, should be regarded as atypical absences; they are probably better classified as tonic seizures (5,14). Similarly, staring spells with generalized fast rhythms or diffuse EEG flattening are occasionally observed without tonic seizures or Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (38,42). Some episodes represent partial seizures from occult frontal lobe foci, whereas others remain unclassified (46,55,56). Generalized fast activity has also been described during (clinically) typical absence seizures (57).

Mixed Patterns

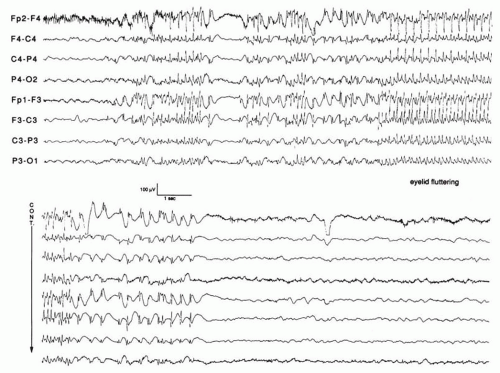

Exceptional patients with staring spells show mixed slow and diffuse fast rhythms during attacks (Fig. 19.3), whose nosologic position is uncertain. The fast rhythms are likely caused by a neurophysiologic mechanism different from that of spike-and-wave discharges. Until the neurobiologic differences of these discharges are better understood, the value of classification will remain dubious.

DIAGNOSIS

Establishing the diagnosis of typical absences is usually not difficult. Staring spells reported by parents or schoolteachers and observation of attacks induced by hyperventilation raise the suspicion, which can be confirmed by a single electroencephalogram recording. Provided that hyperventilation is well performed, the lack of spike-and-wave discharges should cast serious doubt on the diagnosis of typical absence seizures. If 3 minutes of hyperventilation is ineffective, an extension to 5 minutes may be valuable. In adults, typical absences may be mild and inconspicuous, occurring infrequently with only incomplete loss of awareness. Momentary lack of concentration (“phantom absences”) or experiential phenomena could be misinterpreted as complex partial seizures or psychogenic events (19).

Atypical absences rarely will be the sole clinical feature of an epileptic syndrome, but this eventuality can signal a more sinister disorder with mental retardation and multiple other seizure types, particularly tonic and atonic attacks (15,58).

Seizure Type Versus Epileptic Syndrome

Although interesting descriptively, the distinctions among multiple subtypes of typical absences likely have no clinical or neurobiologic significance (59). The important and practical diagnosis is that of idiopathic generalized epilepsy with absence seizures (60), as explained in Chapter 25. Similarly, atypical absence and its variants indicate a diagnosis of symptomatic or cryptogenic generalized epilepsy of the Lennox-Gastaut type. It is the syndromic diagnosis, not the identification of the seizure type, which is most useful for management (61).

Differential Diagnosis

Distinguishing absence seizures from simple daydreaming and inattentiveness is a common challenge in pediatrics. Many children are occasionally inattentive; this is a very common complaint in the outpatient setting. The family or teacher reports brief episodes of staring and unresponsiveness with no significant motor manifestations. Is the child having absence seizures or innocent nonepileptic staring spells? Based on a questionnaire given to parents, several features were identified that can help distinguish the two scenarios in otherwise normal children (62). Three features suggest nonepileptic events: (a) the events do not interrupt play; (b) the events were first noticed by a professional,

such as a schoolteacher, speech therapist, occupational therapist, or physician (rather than by a parent); and (c) the staring child is responsive to touch, or “interruptible” by other external stimuli. These features each have approximately 80% specificity for suggesting nonepileptic staring episodes. Several factors are associated with an epileptic etiology, including twitches of the arms or legs, loss of urine, or upward eye movement. Thus, video-EEG monitoring may not be necessary in otherwise normal children with staring spells, a normal routine EEG, positive responses to the nonepileptic types of questions, and no positive responses to the epileptic types of questions. Other features that are suggestive of nonepileptic or behavioral, rather than epileptic, staring include lower age and lower frequency of episodes (63). Similarly, sustained inattention is more often associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder than with absence seizures (64).

such as a schoolteacher, speech therapist, occupational therapist, or physician (rather than by a parent); and (c) the staring child is responsive to touch, or “interruptible” by other external stimuli. These features each have approximately 80% specificity for suggesting nonepileptic staring episodes. Several factors are associated with an epileptic etiology, including twitches of the arms or legs, loss of urine, or upward eye movement. Thus, video-EEG monitoring may not be necessary in otherwise normal children with staring spells, a normal routine EEG, positive responses to the nonepileptic types of questions, and no positive responses to the epileptic types of questions. Other features that are suggestive of nonepileptic or behavioral, rather than epileptic, staring include lower age and lower frequency of episodes (63). Similarly, sustained inattention is more often associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder than with absence seizures (64).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree