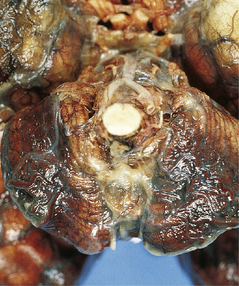

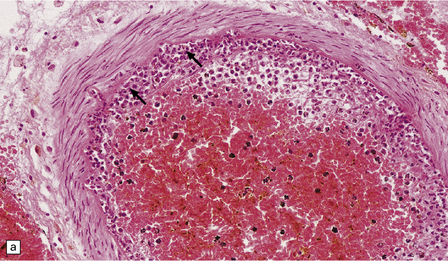

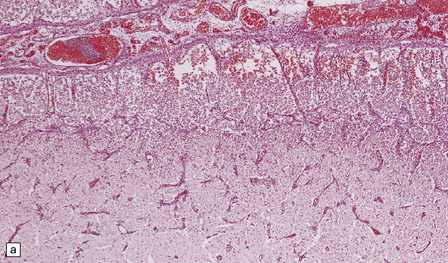

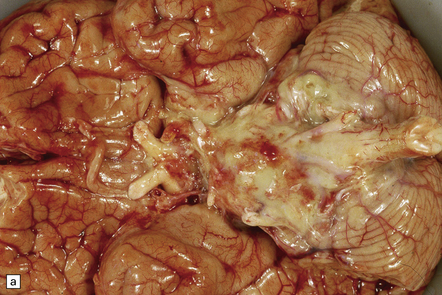

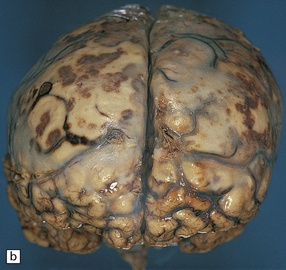

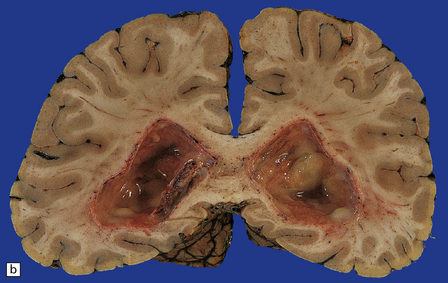

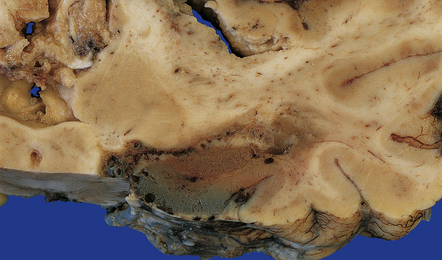

15 The brain is swollen and congested. Hemorrhagic infarcts are common and may be extensive (Fig. 15.1), and a purulent exudate is seen over the cerebral hemispheres or the base of the brain or both (Fig. 15.2). The ventricles may appear compressed by the swollen cerebral hemispheres, or distended if the aqueduct has been obstructed by purulent material. There may be coexistent cerebral abscesses, particularly in association with Citrobacter diversus or Proteus mirabilis meningitis. 15.1 Neonatal meningitis caused by group B streptococcus. Inflammatory cells tend to infiltrate the walls of leptomeningeal and cortical arteries and veins (Fig. 15.3). Intimal accumulations of inflammatory cells may be a prominent feature. Venous thrombosis and infarction are often evident (Figs 15.1, 15.3) and may be extensive. 15.3 Neonatal bacterial meningitis. Complications of acute meningitis are: 15.4 Neonatal bacterial meningitis. The brain is swollen and the leptomeninges are congested. A purulent exudate is seen in the subarachnoid space over the cerebral hemispheres and the base of the brain (Fig. 15.5a), and accumulating in the basal cisterns and cerebral sulci. The exudate associated with pneumococcal infections is often particularly prominent over the cerebral convexities (Fig. 15.5b). There may be little or no macroscopically discernible exudate in patients dying very acutely or those who have been partially treated with antibiotics. Sectioning of the brain may reveal edematous white matter and compressed ventricles or ventricular enlargement due to obstructive hydrocephalus. There is usually purulent fluid within the ventricles. The ventricular exudate may be pronounced in patients with ventricular shunt infection (Fig. 15.6), in whom the leptomeninges appear remarkably clear. Occasionally, the coagulopathy associated with meningococcal septicemia is complicated by ventricular hemorrhage. Small infarcts may result from thrombosis of penetrating arteries (Fig. 15.7). Venous thrombosis and hemorrhagic infarcts are less common than in neonatal meningitis. 15.5 Bacterial meningitis. 15.6 Ventriculitis due to Staphylococcus aureus shunt infection. 15.7 Proteus meningitis.

Acute bacterial infections and bacterial abscesses

ACUTE BACTERIAL MENINGITIS

MACROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

There is focal left temporal infarction (arrow) with thrombosis of the overlying meningeal blood vessels. Elsewhere the meninges are markedly congested and there is blood in the subarachnoid space. (Courtesy of Dr Helen Porter, Bristol Children’s Hospital, UK.)

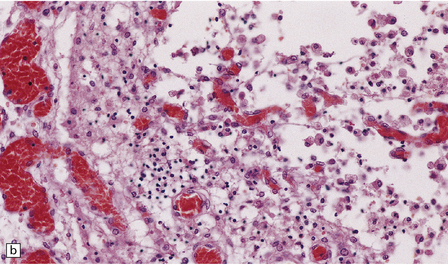

MICROSCOPIC APPEARANCES

(a) Intimal infiltration of meningeal artery by neutrophils (arrows). (b) Inflammatory cell infiltration and thrombosis of small cortical veins with acute infarction of the surrounding tissue.

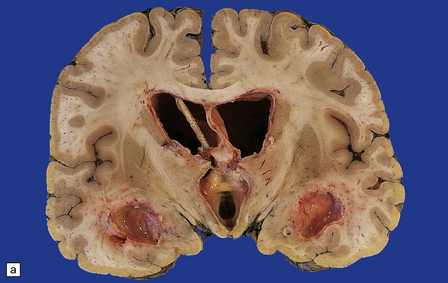

COMPLICATIONS

Obstructive (non-communicating) or communicating hydrocephalus (see Chapter 5).

Obstructive (non-communicating) or communicating hydrocephalus (see Chapter 5).

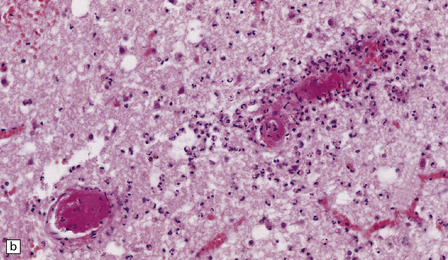

Cavitation of cerebral gray (Fig. 15.4) and white matter.

Cavitation of cerebral gray (Fig. 15.4) and white matter.

(a) Extensive superficial cavitation of cerebral cortex in a case of neonatal group B streptococcal meningitis. (b) At higher magnification the cortex is seen to consist of cystic spaces containing newly formed blood vessels, foamy macrophages, and scattered lymphocytes.

ACUTE BACTERIAL MENINGITIS IN CHILDREN AND ADULTS

(a) A thick basal exudate is evident, encasing the cranial nerves. (b) In this case of pneumococcal meningitis, the brain is swollen with a purulent exudate over the cerebral convexities and foci of infarction in the underlying cortex.

(a) The shunt tubing is visible in one of the lateral ventricles. The ventricles are dilated and their lining markedly congested. (b) The purulent exudate is well seen in the occipital horns.

There are multiple foci of infarction (one involving the hippocampus) due to arterial thrombosis.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Acute bacterial infections and bacterial abscesses