Figure 87.1. Brain computed tomography of a patient with intraventricular hemorrhage of cerebellar origin and associated hydrocephalus.

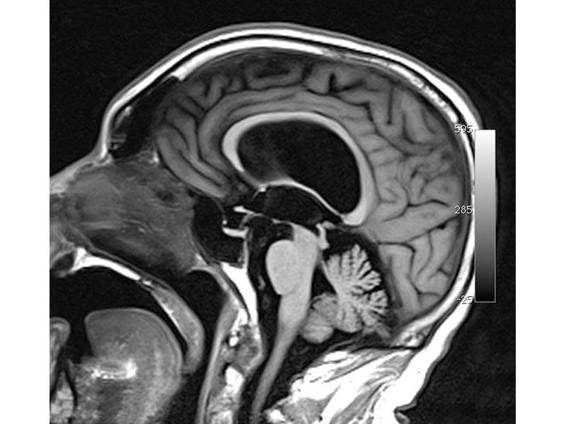

The clinical presentation is not specific; characteristic symptoms and signs include: elevated intracranial pressure, reduced consciousness, nausea and vomiting, occasional signs of meningeal irritation due to mechanical traction of the meninges. In advanced stages, lower limb motor weakness with pyramidal signs is frequently found on neurological examination. Papilledema is common in advanced stages. Although the syndrome of intracranial hypertension is simple to identify and familiar to most medical professionals in neuroscience, it is frequently superimposed over an underlying cause: subarachnoid hemorrhage, intracerebral hemorrhage, midline shift with “trapped ventricles”, and brain tumours among others. Seeking the causes of this complication in high-risk patients presenting with an unexplained decrease in consciousness is therefore essential. The degree of risk is stratified according to risk factors. Imaging studies such as CT of the brain are needed to confirm the diagnosis. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) is the most appropriate study for obtaining a more accurate anatomical definition (Figure 87.2). Additionally, although of limited use, scales such as the bi-caudate index (size of the frontal caudate ventricles divided by the diameter of the skull at that level) can provide objective values for monitoring patients.

Figure 87.2. MRI (sagittal section) of patients with hydrocephalus associated with aqueduct stenosis.

87.4 Treatment

In addition to treating the underlying disease, the emergency treatment of acute hydrocephalus syndrome involves placement of an external ventricular drain (EVD [1,2] via ventriculostomy or intraventricular catheters (IVC).

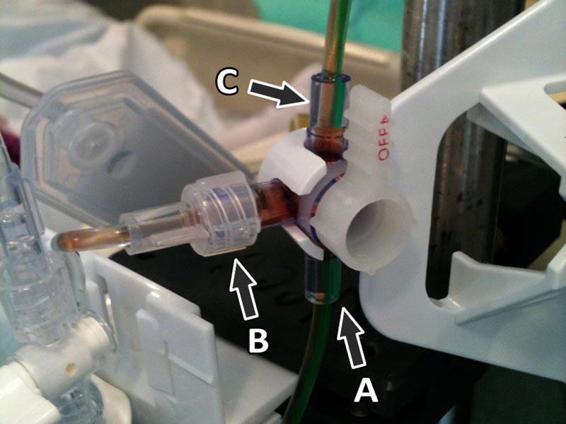

The most common indication for catheter insertion is a reduced level of consciousness in patients with a radiographic diagnosis of acute hydrocephalus. A description of techniques for external ventricular drainage is beyond the scope of this chapter. The reader is referred to the references listed at the end of this chapter. In general, after insertion of the IVC, the necessary connections are completed (Figures 87.3 and 87.4).

Figure 87.3. Ventricular drainage system.

Figure 87.4. Three-way valve with the patient connected (A) to the transducer (B) and the reservoir (C).

The IVC is connected to a 3-way valve. One line is connected to the drainage chamber, the second to the IVC, and the third to a pressure transducer. Intracranial pressure (ICP) can only be measured after closing the valve to drain the chambers. This will produce a single column of liquid in contact with the membrane transduction.

Management of the IVC will vary depending on the etiology of acute hydrocephalus; however, some general principles are valid and deserve to be discussed:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree