Adjacent Segment Disease

Krzysztof B. Siemionow

Frank M. Phillips

Cervical spinal procedures, such as anterior cervical discectomy and fusion, generally yield excellent results in patients suffering from the effects of spinal cord or nerve root compression. With long-term follow-up, it has been noted that although the majority of patients remain free of symptoms, a significant percentage develop degenerative changes at levels adjacent to the fusion. While this phenomenon has been well described in the literature, controversy remains as to the etiology of the problem. As with most degenerative processes, the causes are likely multifactorial, potentially involving biomechanical changes at the level above and below the fusion, the natural history of cervical spondylosis, and the surgical insult to surrounding soft tissues. When symptomatic, adjacent segment degenerative changes pose a significant clinical challenge and may require further surgical intervention. Recently, motion-sparing technologies have been developed with a specific goal of reducing the incidence of adjacent segment disease. The purpose of this chapter is to review the effects of surgery, fusion, and trauma on the development of adjacent segment disease in the cervical spine.

ADJACENT SEGMENT DISEASE AFTER FUSION FOR CERVICAL DEGENERATIVE DISEASE

The development of radiographic degenerative changes adjacent to a previous anterior cervical fusion has been reported by numerous authors. In a short-term follow-up MRI study, Kulkarni et al. (1) demonstrated that levels adjacent to the fused segment exhibited more pronounced degenerative changes (compared with remote levels) in 75% of patients who had undergone one- or two-level corpectomy and fusion. Gore and Sepic (2) observed new spondylosis in 25% of 121 patients and progression of preexisting spondylosis in another 25% of patients who had previously undergone anterior cervical fusion with an average follow-up of 5 years. Baba et al. (3) assessed over 100 patients undergoing anterior cervical fusion for cervical myelopathy with an average of 8.5 years of followup. Postoperatively, increased flexion-extension at the adjacent level cephalad to the fusion was observed. The authors observed that 25% of the patients subsequently developed new spinal canal stenosis above the previously fused segments.

Although there exists no doubt that degenerative change occur at the levels adjacent to a cervical fusion, controversy exists as to their etiology. Although the clinical studies cited suggest a significant incidence of degeneration adjacent to fusion, some authors have suggested that natural history may be the critical factor in the development of this process. Herkowitz et al. (4) studied 44 patients who had been randomized to anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (n = 28) or dorsal foraminotomy (n= 16) without fusion for the treatment of cervical radiculopathy. Preoperative x-rays were compared to those at final follow-up (mean 4.5 years), and among the group undergoing ventral fusion, 41% developed adjacent segment degeneration. Fifty percent of the patients undergoing dorsal foraminotomy (with partial facetectomy) without fusion developed adjacent level degeneration, implying that fusion may not be the primary factor in development of adjacent level degeneration. There was no correlation between the development of adjacent segment degeneration and the onset of new clinical symptoms referable to the level and site of the reported radiographic changes.

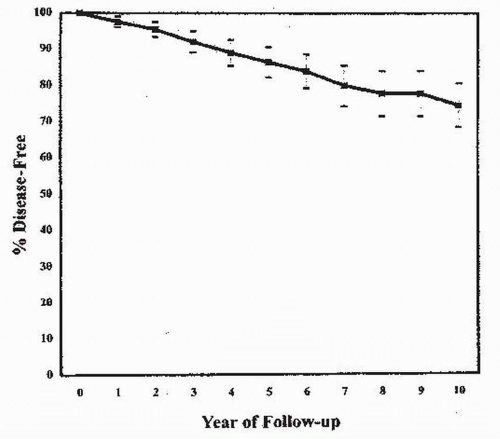

Hilibrand et al. (5) defined symptomatic adjacent segment disease as new clinical symptoms that persisted for two consecutive follow-up visits after ventral cervical fusion. Symptomatic adjacent segment disease occurred at a relatively constant incidence of 2.9% per year during the 10-year follow-up from the index fusion operation. Survivorship analysis predicted that 25.6% of the patients who had a ventral cervical arthrodesis would have symptomatic new disease at an adjacent level within 10 years after the operation (Fig. 116.1). There were highly significant differences among specific motion segments with regard to the likelihood of symptomatic adjacent segment disease; the greatest risk was at the interspaces between the fifth and sixth and between the sixth and seventh cervical vertebrae. Of note, these are the levels most frequently affected by symptomatic cervical spondylosis without previous fusion. Interestingly, the authors reported that the risk of new disease at an adjacent level was significantly lower following a multilevel arthrodesis than it was following a single-level arthrodesis. This would seem counterintuitive if altered biomechanics were the primary cause of adjacent

level degeneration, as fusing multiple levels theoretically places even greater stresses on the adjacent mobile levels. Hilibrand et al. (5) also reported a close correlation between the risk of symptomatic adjacent segment disease and increased preoperative motion at a given level (6). The authors concluded that degenerative changes at the most mobile segments of the cervical spine may reflect the underlying preoperative kinematics rather than the effects of an adjacent arthrodesis.

level degeneration, as fusing multiple levels theoretically places even greater stresses on the adjacent mobile levels. Hilibrand et al. (5) also reported a close correlation between the risk of symptomatic adjacent segment disease and increased preoperative motion at a given level (6). The authors concluded that degenerative changes at the most mobile segments of the cervical spine may reflect the underlying preoperative kinematics rather than the effects of an adjacent arthrodesis.

In a study reported by Ishihara et al. (7), symptomatic adjacent segment disease developed in 19 of 112 patients following cervical fusion. Using a Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, the disease-free survival rates were 89% at 5 years, 84% at 10 years, and 67% at 17 years. The incidences of dural indentation secondary to spondylosis or disc protrusion at the adjacent level were significantly higher in symptomatic cases. Seven cases (6%) that failed nonoperative treatment required additional surgical intervention.

Adjacent level degeneration after a prior cervical fusion is not a benign condition and may lead to additional surgery. In Hilibrand’s study, 14% of patients required additional cervical surgery after cervical fusion over a range of follow-up from 2 to 21 years (5). Other authors have reported the annual incidence of adjacent segment disease requiring additional surgery to be between 1.5% and 4% (2,8,9).

Several authors have reported the rate of adjacent segment degeneration in patients undergoing cervical procedures without fusion. Interpretation of these studies is limited by their shorter follow-up duration. Aydin et al. (10) performed 216 ventral microdiscectomies without fusion for cervical disk herniation at one or two adjacent levels (10). The authors reported adjacent segment disease in two patients at a mean follow-up of 27 months. Sasai et al. (11) reported their experience with the treatment of myelopathy and myeloradiculopathy in 30 patients with microsurgical dorsal herniotomy with en bloc laminoplasty. They reported no adjacent level changes and preservation of preoperative range of motion (ROM) at 28 months. Balasubramanian et al. (12) treated 34 patients suffering from radiculopathy with a ventral microforaminotomy. Two of their patients (6%) developed symptoms at adjacent levels requiring an anterior cervical discectomy fusion (ACDF) at an average follow-up of 5.4 months. In 334 patients who underwent anterior cervical discectomy with and without fusion, Lunsford et al. (13) found an overall prevalence of adjacent segment disease of approximately 7% and an annual incidence of approximately 2.5%. The authors did not find any difference in the rate of adjacent segment disease between patients who underwent discectomy with fusion and those who underwent discectomy alone at an average follow-up of 3 years. Henderson reported a prevalence of adjacent level degeneration of 9% and an average annual incidence of approximately 3% in 846 patients who underwent dorsal foraminoto my without fusion (14). Seventy-nine of the eight hundred forty-six patients (9%) developed adjacent segment disease requiring additional surgery.

Identified risk factors for the development of adjacent segment disease after fusion include the radiographic evidence of neural element compression at the adjacent levels at the time of the index procedure, as well as surgery performed adjacent to the C5-C6 and/or C6-C7 levels (5). Multilevel ACDF appears to have a lower rate of adjacent segment disease when compared to single-level ACDF.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree