Aetiology

Approaches to aetiology in psychiatry

General issues relating to aetiology

The historical development of ideas of aetiology

The contribution of scientific disciplines to psychiatric aetiology

Relationship of this chapter to those on psychiatric syndromes

Approaches to aetiology in psychiatry

Psychiatrists are concerned with aetiology in two ways. First, in everyday clinical work they try to discover the causes of the mental disorders presented by individual patients. Secondly, in seeking a wider understanding of psychiatry they are interested in aetiological evidence obtained from clinical studies, community surveys, or laboratory investigations. Correspondingly, the first part of this chapter deals with some general issues relating to aetiology in the assessment of the individual patient, while the second part deals with the various scientific disciplines that have been applied to the study of aetiology.

General issues relating to aetiology

Aetiology and intuitive understanding

When the clinician assesses an individual patient, he draws on a common fund of aetiological knowledge that has been derived from the study of groups of similar patients, but he cannot understand the patient in these terms alone. He also has to use everyday insights into human nature. For example, when assessing a depressed patient, the psychiatrist should certainly know what has been discovered about the psychological and neuro-chemical changes that accompany depressive disorders, and what evidence there is about the aetiological role of stressful events, and about genetic predisposition to depressive disorder. At the same time he will need intuitive understanding in order to recognize, for example, that this particular patient feels depressed because he has learned that his wife has cancer.

Common-sense ideas of this kind are an important part of aetiological formulation in psychiatry, but they must be used carefully if superficial explanation is to be avoided. Aetiological formulation can be done properly only if certain conceptual problems are clearly understood. These problems can be illustrated by a case history.

When thinking about the causes of this woman’s symptoms, the clinician would first draw on knowledge of aetiology derived from scientific enquiries. Genetic investigations have shown that if a parent suffers from mania as well as depressive disorder, a predisposition to depressive disorder is particularly likely to be transmitted to the children. Therefore it is possible that this patient received this predisposition from her mother.

Clinical investigation has also provided some information about the effects of separating children from their parents. In the present case, the information is not helpful because it refers to people who were separated from their parents at a younger age than the patient. On scientific grounds there is no particular reason to focus on the departure of the patient’s father, but intuitively it seems likely that this was an important event. From everyday experience it is understandable that a woman should feel very upset if her husband leaves her. It is also understandable that she is likely to feel even more distressed if this event recapitulates a related distressing experience in her own childhood. Therefore the clinician would recognize intuitively that the patient’s depression is likely to be a reaction to the husband’s departure. The same sort of intuition might suggest that the patient would start to feel better when her husband came back. In the event she did not recover. Although her symptoms seemed understandable when her husband was away, they seemed less so after his return.

This simple case history illustrates some important aetiological issues in psychiatry:

• the complexity of causes

• the classification of causes

• the concept of stress

• the concept of psychological reaction

• the relative roles of intuition and scientific knowledge in aetiological formulations.

The complexity of causes in psychiatry

In psychiatry, the study of causation is complicated by three problems. These problems are encountered in other branches of medicine, but to a lesser degree.

Lack of temporal association

The first problem is that causes are often remote in time from the effects that they produce. For example, it is widely believed that childhood experiences partly determine the occurrence of emotional difficulties in adult life. It is difficult to test this idea, because the necessary information can only be gathered either by studying children and tracing them many years later, which is difficult, or by asking adults about their childhood experiences, which is unreliable.

Cause and effect

The second problem is that a single cause may lead to several effects. For example, being deprived of parental affection in childhood has been reported to predispose to antisocial behaviour, suicide, depressive disorder, and several other disorders. Conversely, a single effect may arise from several causes. The latter can be illustrated either by different causes in different individuals or by multiple causes in a single individual. For example, learning disability (a single effect) may occur in several children, but the cause may be a different genetic abnormality in each child. On the other hand, depressive disorder (a single effect) may occur in one individual through a combination of causes, such as genetic factors, adverse childhood experiences, and stressful events in adult life.

Indirect mechanisms

The third problem is that aetiological factors in psychiatry rarely exert their effects directly. For example, the genetic predisposition to depression may be mediated in part through psychological factors which make it more likely that the individual concerned will experience adverse life events. Thus aetiological effects are usually mediated through complex intervening mechanisms which also need to be investigated and understood.

The classification of causes

A single psychiatric disorder, as just explained, may result from several causes. For this reason a scheme for classifying causes is required. A useful approach is to divide causes chronologically into those that are predisposing, precipitating, and maintaining.

Predisposing factors

These are factors, many of them operating from early in life, that determine a person’s vulnerability to causal factors acting close to the time of the illness. They include genetic endowment and the environment in utero, as well as physical, psychological, and social factors in infancy and early childhood. The term ‘constitution’ is often used to describe the mental and physical make-up of a person at any point in their life. This make-up changes as life goes on under the influence of further physical, psychological, and social influences. Some writers restrict the term constitution to the make-up at the beginning of life, while others also include characteristics that are acquired later (this second usage is adopted in this book). The concept of constitution includes the idea that a person may have a predisposition to develop a disorder (e.g. schizophrenia) even though the latter never manifests itself. From the standpoint of psychiatric aetiology, one of the important parts of the constitution is the personality.

When the aetiology of an individual case is formulated, the personality is always an essential element. For this reason, the clinician should be prepared to spend sufficient time talking to the patient and to people who know them in order to build up a clear picture of their personality. This assessment often helps to explain why the patient responded to certain stressful events, and why they reacted in a particular way. The obvious importance of personality in the individual patient contrasts with the small amount of relevant scientific information so far available. Therefore when evaluating personality it is particularly important to acquire sound clinical skills through supervised practice.

Precipitating factors

These are events that occur shortly before the onset of a disorder and which appear to have induced it. They may be physical, psychological, or social. Whether they produce a disorder at all, and what kind of disorder, depends partly on constitutional factors in the patient (as mentioned above). Examples of physical precipitants include cerebral tumours and drugs. Psychological and social precipitants include personal misfortunes such as the loss of a job, and changes in the routine of life, such as moving home. Sometimes the same factor can act in more than one way. For example, a head injury can induce psychological disorder either through physical changes in the brain or through its stressful implications for the patient.

Maintaining factors

These factors prolong the course of a disorder after it has been provoked. When planning treatment, it is particularly important to pay attention to these factors. The original predisposing and precipitating factors may have ceased to act by the time that the patient is seen, but the maintaining factors may well be treatable. For example, in their early stages many psychiatric disorders lead to secondary demoralization and withdrawal from social activities, which in turn help to prolong the original disorder. It is often appropriate to treat these secondary factors, whether or not any other specific measures are carried out. Maintaining factors are also called perpetuating factors.

The concept of stress

Discussions about stress are often confusing because the term is used in two ways. First, it is applied to events or situations, such as working for an examination, which may have an adverse effect on someone. Secondly, it is applied to the adverse effects that are induced, which may involve psychological or physiological change. When considering aetiology it is advisable to separate these components.

The first set of factors can usefully be called stressors. They include a large number of physical, psychological, and social factors that can produce adverse effects. The term is sometimes extended to include events that are not experienced as adverse at the time, but which may still have adverse long-term effects. For example, intense competition may produce an immediate feeling of pleasant tension, although it may sometimes lead to unfavourable long-term effects.

The effect on the person can usually be called the stress reaction, to distinguish it from the provoking events. This reaction includes autonomic responses (e.g. a rise in blood pressure), endocrine changes (e.g. the secretion of adrenaline and noradrenaline), and psychological responses (e.g. a feeling of being keyed up). Much current neurobiology research is involved in studying the effects of stress on the brain, and in particular how stress affects the mechanisms involved in the regulation of mood and processing of emotional information (see Chapter 8).

The concept of a psychological reaction

As already mentioned, it is widely recognized that psychological distress can occur as a reaction to unpleasant events. Sometimes the association between event and distress is evident—for example, when a woman becomes depressed after the death of her husband. In other cases it is far from clear whether the psychological disorder is really a reaction to an event, or whether the two have coincided fortuitously—for example, when a person becomes depressed after the death of a distant relative.

Jaspers (1963, p. 392) suggested three criteria for deciding whether a psychological state is a reaction to a particular set of events:

• The events must be adequate in severity and closely related in time to the onset of the psychological state.

• There must be a clear connection between the nature of the events and the content of the psychological disorder (in the example just given, the person should be preoccupied with ideas concerning their distant relative).

• The psychological state should begin to disappear when the events have ceased (unless, of course, it can be shown that perpetuating factors are acting to maintain it).

These three criteria are useful in clinical practice, although they can be difficult to apply (particularly the second criterion).

Understanding and explanation

As already mentioned, aetiological statements about individual patients must combine knowledge derived from research on groups of patients with intuitive understanding derived from everyday experience. Jaspers (1963, p. 302) has called these two ways of making sense of psychiatric disorders ‘Erklären’ and ‘Verstehen’, respectively.

In German, these terms mean ‘explanation’ and ‘understanding’, respectively, and they are usually translated as such in English translations of Jaspers’ writing. However, Jaspers used them in a special sense. He used ‘Erklären’ to refer to the sort of causative statement that is sought in the natural sciences. It is exemplified by the statement that a patient’s aggressive behaviour has occurred because he has a brain tumour. He used ‘Verstehen’ to refer to psychological understanding, or the intuitive grasp of a natural connection between events in a person’s life and his psychological state. In colloquial English, this could be called ‘putting oneself in another person’s shoes.’ It is exemplified by the statement ‘I can understand why the patient became angry when her children were shouted at by a neighbour.’

These distinctions are reasonably clear when we consider an individual patient, but confusion sometimes arises when attempts are made to generalize from insights obtained in a single case to widely applicable principles. Understanding may then be mistaken for explanation. Jaspers suggested that some psychoanalytical ideas are special kinds of intuitive understanding that are derived from the detailed study of individuals and then applied generally. They are not explanations that can be tested scientifically. They are more akin to insights into human nature that can be gained from reading great works of literature. Such insights are of great value in conducting human affairs. It would be wrong to neglect them in psychiatry, but equally wrong to see them as statements of a scientific kind.

The aetiology of a single case

How to make an aetiological formulation was discussed in Chapter 3 (see p. 64). An example was given of a woman in her thirties who had become increasingly depressed. The formulation showed how aetiological factors could be grouped under headings of predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating factors. It also showed how information from scientific investigations (in this case genetics) could be combined with an intuitive understanding of personality and the likely effects of family problems on the patient. The reader may find it helpful to re-read the formulation on p. 64 before continuing with this chapter.

Aetiological models

Before considering the contribution that different scientific disciplines can make to psychiatric aetiology, attention needs to be given to the kinds of aetiological model that have been employed in psychiatry. A model is a device for ordering information. Like a theory, it seeks to explain certain phenomena, but it does so in a broad and comprehensive way that cannot readily be proved false.

Reductionist and non-reductionist models

Two broad categories of explanatory model can be recognized. Reductionist models seek to understand causation by tracing back to increasingly simple early stages. Examples include the ‘narrow’ medical model, which is described below, and the psychoanalytic model. This type of model can be exemplified by the statement that the cause of schizophrenia lies in disordered neurotransmission in a specific area of the brain.

Non-reductionist models try to relate problems to wider rather than narrower issues. The explanatory models that are used in sociology are generally of this kind. In psychiatry, this type of model can be exemplified by the statement that the cause of a patient’s schizophrenia lies in his family; the patient is the most conspicuous element in a disordered group of people. In the same way it can be asserted that certain depressive states are associated with indices of social deprivation and isolation, and can be best understood as being caused by these factors.

The neuroscience approach

The technical and conceptual advances in brain sciences have led to what is often called the neuroscience approach. Kandel (1998) has outlined the key assumptions underlying this approach to aetiology, which can be summarized as follows.

• All mental processes derive from operations of the brain. Thus all behavioural disorders are ultimately disturbances of brain function, even where the original ‘cause’ is clearly environmental.

• Genes have important effects on brain function and therefore exert significant control over behaviour.

• Social and behavioural factors exert their effects on the brain in part through changes in gene expression. Changes in gene expression leading to altered patterns of synaptic connectivity underlie the ability of experiences such as learning and psychotherapy to change behaviour.

The latter concept derives from the ability of a wide range of environmental stimuli to modulate gene expression by various mechanisms, including epigenetic modifications (see below). Thus while genes coding for particular proteins are inherited, environmental and developmental influences are involved in determining whether and to what extent a particular gene is expressed. This provides a plausible mechanism by which nature and nurture interact in the production of a behavioural phenotype.

The neuroscience approach therefore seeks to comprehend the role of social, family, and personal factors in behaviour by relating them to changes in brain function. For example, in understanding the effect of childhood neglect on liability to adult depression, it is important to find out how adverse childhood experiences might alter relevant brain mechanisms (e.g. the endocrine response to stress), and how this abnormality might predispose to depression when the individual is exposed to difficulties in adulthood. Thus, although a neuroscience approach encompasses the importance of social and personal factors, it seeks to understand their consequences in a reductionist way.

Medical models

Several models are used in psychiatric aetiology, but the so-called medical model is the most prominent one. It represents a general strategy of research that has proved useful in medicine, particularly in studying infectious diseases. A disease entity is identified in terms of a consistent pattern of symptoms, a characteristic clinical course, and specific biochemical and pathological findings (see Chapter 2 regarding models of disease). When an entity has been identified in this way, a set of necessary and sufficient causes is sought. In the case of tuberculosis, for example, the tubercle bacillus is the necessary cause, but it is not by itself sufficient. However, the tubercle bacillus in conjunction with either poor nutrition or low resistance is sufficient cause.

The importance of social and cultural factors in the presentation and course of illness is now well recognized in general medicine, and modern medical models are therefore considerably broader than those based on the elucidation of the mechanism of infectious disease. Modern medical models also recognize that much illness is characterized by quantitative rather than qualitative deviations from normal (e.g. high blood pressure). This applies to certain disorders in psychiatry, particularly anxiety and milder depressive disorders, which can therefore be accommodated in a broad medical model.

Difficulties with the medical model arise particularly in relation to disorders that are characterized principally by abnormalities of conduct and social behaviour, such as antisocial behaviour and substance misuse. As mentioned above, current neuroscience approaches would seek to understand these disorders through changes in the relevant brain systems. This is because causal factors in abnormal social behaviour, such as environmental hardship and personal deprivation, must ultimately express their effects on behaviour through changes in brain mechanisms.

Although the latter view appears theoretically valid and increases the aetiological power of the medical model, the key decision for both clinician and policy maker is at what level the disorder is best understood and managed. For example, it is possible to understand problems in substance misuse as arising from a defect in brain reward systems which, in a vulnerable individual, results in ‘normal’ experimentation with illicit substances leading to substance misuse, with adverse personal and social consequences. Equally, one can see excessive drug misuse in society as a ‘symptom’ of social deprivation and family disruption (see Chapter 17). Both kinds of aetiology can be comprehended in a broad medical model, but different forms of intervention would result.

The behavioural model

As explained above, certain disorders that psychiatrists treat, particularly those defined in terms of abnormal behaviour, do not fit readily into the medical model. The latter include deliberate self-harm, the misuse of drugs and alcohol, and repeated acts of delinquency. The behavioural model is an alternative way of comprehending these disorders. In this model the disorders are explained in terms of factors that determine normal behaviour. These include drives, reinforcements, social and cultural influences, and internal psychological processes such as attitudes, beliefs, and expectations. The behavioural model predicts that there will not be a sharp distinction between the normal and the abnormal, but a continuous gradation. This model can therefore be a useful way of considering many of the conditions that are seen by psychiatrists.

Although the behavioural model is mainly concerned with psychological and social causes, it does not exclude genetic, physiological, or biochemical causes. This is because normal patterns of behaviour are partly determined by genetic factors, and because psychological factors such as reinforcement have a basis in physiological and biochemical mechanisms. Also, the behavioural model employs both reductionist and non-reductionist explanations. For example, abnormalities of behaviour can be explained in terms of abnormal conditioning (a reductionist model), or in terms of a network of social influences.

Developmental models

Medical and behavioural models incorporate the idea of predisposing as well as precipitating causes (i.e. the idea that past events may determine whether or not a current cause gives rise to a disorder). Some models place even more emphasis on past events in the form of a sequence of experiences leading to the present disorder. This approach has been called the ‘life story’ approach to aetiology. One example is Freud’s psychoanalysis (see Box 5.1), and another is Meyer’s psychobiology. These ideas are considered further below.

Political models (‘anti-psychiatry’, ‘critical psychiatry’)

The models outlined above rely on a scientific approach to psychiatric aetiology. This implies that psychiatric disorders, like other medical conditions, can be studied and understood in an objective and empirical way using the methods of natural sciences. In the history of psychiatry this view has often been regarded as far from self-evident, and other conceptual frameworks have sometimes been advocated. For example, it was customary in the Middle Ages to explain mental illness in terms of demonic possession and witchcraft (see below). Over the last 50 years, however, criticisms of scientific approaches to aetiology have most often taken the view that psychiatric illness is defined by social and political imperatives, and represents at best a cultural value judgement and at worst an abusive means of social control.

Arguments of this nature were put forward strongly by the French philosopher, Michel Focault (1926–1984), and were further developed by psychiatrists such as RD Laing (1927–1989), who employed a phenomenological approach to argue that schizophrenia is an understandable response of an individual to a culture of exploitation and alienation. Lack of faith in a scientific approach to mental experience was exemplified by the psychiatrist Thomas Szasz, who commented that ‘There is no psychology; there is only biography and autobiography.’ These ideas are sometimes called ‘anti-psychiatry’ to emphasize their fundamental contrast with the medical models employed by conventional psychiatry.

Most psychiatrists have believed that these formulations do not advance the understanding of mental illness, and in fact provide rather poor explanations of the range of clinical psychopathology. For example, they seem unable to account for the existence of schizophrenia in all human societies (see Chapter 11). However, political perceptions of psychiatry are important because they have powerful effects on how mentally ill people are treated and on what services are provided (see Chapter 21). Furthermore, there is no doubt that political abuse of psychiatric patients has occurred, as demonstrated by the cooperation of many German psychiatrists with the euthanasia programmes of the Nazi regime (Torrey and Yolken, 2010).

While this is an extreme and abhorrent example, political analyses of psychiatric practice highlight the need for the rights of patients to be respected and their experiences understood in a personal and social context as outlined above. (For a discussion of the limits of scientific approaches to psychiatric illness, see Thomas and Bracken, 2004.)

The historical development of ideas of aetiology

From the earliest times, theories of the causation of mental disorder have recognized both somatic and psychological influences. Greek medical literature referred to the causes of mental disorders, mainly in the Hippocratic writings (fourth century BC). Serious mental illness was ascribed mainly to physical causes, which were represented in the theory that health depended on a correct balance of the four body ‘humours’ (blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile). Melancholia was ascribed to an excess of black bile. Most of the less severe psychiatric disorders were thought to have supernatural causes and to require religious healing. An exception was hysteria, which was thought to be physically caused by the displacement of the uterus from its normal position. Nowadays hysteria is attributed mainly to psychological causes.

Roman physicians generally accepted the causal theories of Greek medicine, and developed them in some respects. Galen accepted that melancholia was caused by an excess of black bile, but suggested that this excess could result either from cooling of the blood or from overheating of yellow bile. Phrenitis, the name given to an acute febrile condition with delirium, was thought to result from an excess of yellow bile.

Throughout the Middle Ages these early ideas about the causes of mental illness were largely neglected, although they were maintained by some scholars, such as Bartho-lomeus Anglicus. The causes of mental illness were now formulated in theological terms of sin and evil, with the consequence that many mentally ill people were persecuted as witches. It was not until the middle of the sixteenth century that beliefs in the supernatural and witchcraft were strongly rejected as causes of mental disorder, notably by the Flemish writer Johan Weyer (1515–1588) in his book De Praestigiis Demonum, published in 1563. Earlier, the renowned physician Paracelsus (1491–1541) had emphasized the natural causes of mental illness.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, a more scientific approach to the causation of mental illness developed as physicians became interested in mental disorders, mainly hysteria and melancholia. The English physician Thomas Willis attributed melancholia to ‘passions of the heart’, but considered that madness (illnesses with thought disorder, delusions, and hallucinations) was due to a ‘fault of the brain.’ Willis realized that this fault was not a recognizable gross structural lesion, but a functional abnormality. In the terminology of the time, he referred to a disorder of the ‘vital spirits’ that were thought to account for nervous action. He also pointed out that hysteria could not be caused by a displacement of the womb, because the organ is firmly secured in the pelvis.

Another seventeenth-century English physician, Thomas Sydenham, rejected the alternative theory that hysteria was caused by a functional disorder of the womb (‘uterine suffocation’), because he had observed the condition in men. Despite this renewed medical interest in the causes of mental disorder, the most influential seventeenth-century treatise was written by a clergyman, Robert Burton. This work, The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621), described in detail the psychological and social causes (such as poverty, fear, and solitude) that were associated with melancholia and seemed to cause it.

Aetiology depends on nosology. Unless it is clear how the various types of mental disorder relate to one another, little progress can be made in understanding causation. From his observations of patients with psychiatric disorders, the Italian physician, Giovanni Battista Morgagni, became convinced that there was not one single kind of madness, but many different ones (Morgagni, 1769). Further attempts at classification followed. One of the best known was proposed by William Cullen, who included a category of neurosis for disorders not caused by localized disease of the nervous system.

The idea that individual mental disorders are caused by lesions of particular brain areas can be traced back to the theory of phrenology proposed by Franz Gall (1758–1828) and his pupil Johann Spurzheim (1776–1832). Gall proposed that the brain was the organ of the mind, that the mind was made up of specific faculties, and that these faculties originated in specific brain areas. He also proposed that the size of a brain area determined the strength of the faculty that resided in it, and that the size of brain areas was reflected in the contours of the overlying skull. Thus the shape of the head reflected a person’s psychological make-up. Although the last steps in Gall’s argument were erroneous, the ideas of cerebral localization were to develop further. An increased interest in brain pathology led to theories that different forms of mental disorder were associated with lesions in different parts of the brain.

It had long been observed that serious mental illness ran in families, but in the nineteenth century this idea took a new form. Benedict-Augustin Morel (1809–1873), a French psychiatrist, put forward ideas that became known as the ‘theory of degeneration.’ He proposed not only that some mental illnesses were inherited, but also that environmental influences (such as poor living conditions and the misuse of alcohol) could lead to physical changes that could be transmitted to the next generation. Morel also proposed that, as a result of the successive effect of environmental agents in each generation, illnesses appeared in increasingly severe forms in successive generations. It was inherent in these ideas that mental disorders did not differ in kind but only in severity, with neuroses, psychoses, and mental handicap being increasingly severe manifestations of the same inherited process.

These ideas were consistent with the accepted theories of the inheritance of acquired characteristics, and they were widely accepted. They had the unfortunate effect of encouraging a pessimistic approach to treatment. They also supported the Eugenics Movement, which held that the mentally ill should be removed from society in order to prevent them from reproducing. These developments are an important reminder that aetiological theories may give rise to undesirable attitudes to the care of patients.

Mid-nineteenth-century views of the causation of mental illness can be judged from the widely acclaimed textbooks of Jean-Étienne Esquirol, a French psychiatrist, and of Wilhelm Griesinger, a German psychiatrist. Esquirol (1845) focused on the causes of illness in the individual patient, and was less concerned with general theories of aetiology. He recorded psychological and physical factors, which he believed to be significant in individual cases, and he distinguished between predisposing and precipitating causes. He regarded heredity as the most important of the predisposing causes, but he also stressed that predisposition was acted on by psychological causes and by social (at that time called ‘moral’) causes such as domestic problems, ‘disappointed love’, and reverses of fortune. Important physical causes of mental disorder included epilepsy, alcohol misuse, excessive masturbation, childbirth and lactation, and suppression of menstruation. Esquirol also observed that age influenced the type of illness. Thus dementia was not observed among the young, but mania was uncommon in old age. He recognized that personality was often a predisposing factor.

In Pathology and Therapy of Mental Disorders, which was first published in 1845, Griesinger maintained that mental illness was a physical disorder of the brain, and he considered at length the neuropathology of mental illness. He paid equal attention to other causes, including heredity, habitual drunkenness, ‘domestic unquiet’, disappointed love, and childbirth. He emphasized the multiplicity of causes when he wrote:

A closer examination of the aetiology of insanity soon shows that in the great majority of cases it was not a single specific cause under the influence of which the disease was finally established, but a complication of several, sometimes numerous causes, both predisposing and exciting. Very often the germs of the disease are laid in those early periods of life from which the commencement of the formation of character dates. It grows by education and external influences.

(Griesinger, 1867, p. 130)

British views on aetiology in the late nineteenth century can be judged from A Manual of Psychological Medicine by Bucknill and Tuke (1858), and from The Pathology of Mind by Henry Maudsley (1879). Maudsley described the causes of mental disorder in terms similar to those of Griesinger. Thus causes were multiple, while predisposing causes (including heredity and early upbringing) were as important as the more obvious proximal causes. Maudsley held that mistakes in determining causes were often due to ‘some single prominent event, which was perhaps one in a chain of events, being selected as fitted by itself to explain the catastrophe. The truth is that in the great majority of cases there has been a concurrence of steadily operating conditions within and without, not a single effective cause’ (Maudsley, 1879, p. 83).

Although these nineteenth-century writers and teachers of psychiatry emphasized the multiplicity of causes, many practitioners focused narrowly on the findings of genetic and pathological investigations, and adopted a pessimistic approach to treatment. However, Adolf Meyer (1866–1950), a Swiss psychiatrist who worked mainly in the USA, emphasized the role of psychological and social factors in the aetiology of psychiatric disorder. Meyer applied the term psychobiology to this approach, in which a wide range of previous experiences were considered and then common-sense judgements used to decide which experiences might have led to the present disorder. Meyer acknowledged the importance of heredity and brain disorder, but emphasized that these factors were modified by life experiences which often determined whether or not a particular disorder would be clinically expressed. Meyer’s approach remains the basis of the evaluation of aetiology for the individual patient (see p. 83).

The aetiological theories considered so far were mainly concerned with the major mental illnesses. Less severe disorders, particularly those that came to be called neurosis, hysteria, and hypochondriasis, and milder states of depression, were treated mainly by physicians. Pierre Charcot, a French neurologist, carried out extensive studies of patients with hysteria and of their response to hypnosis. He believed that hysteria resulted from a functional disorder of the brain and could be treated by hypnosis. In the USA, Weir Mitchell proposed that conditions akin to mild chronic depression were due to exhaustion of the nervous system—a condition he called neurasthenia.

In Austria, another neurologist, Sigmund Freud, tried to develop a more comprehensive explanation of nervous diseases, first of hysteria and then of other conditions. After an initial interest in physiological causes, Freud proposed that the causes were psychological, but hidden from the patient because they were in the unconscious part of the mind. Freud took a developmental approach to aetiology, believing that the seeds of adult disorder lay in the process of child development (see below). In France, Pierre Janet developed an alternative psychological explanation, which was based on variations in the strength of nervous activity and on narrowing of the field of consciousness.

Interest in psychological explanations of the whole range of mental disorders grew as neuropathological and genetic studies failed to yield new insights. Freud and his followers attempted to extend their theory of the neuroses to explain the psychoses. Although the psychological theory was elaborated, no new objective data were obtained about the causes of severe mental illness. Nevertheless, the theories provided explanations which some psychiatrists found more acceptable than an admission of ignorance. Psychoanalysis became increasingly influential, particularly in American psychiatry, where it predominated until the 1970s. Since that time there has been renewed interest in genetic, biochemical, and neuropathological causes of mental disorder—an approach that has become known as biological psychiatry (Guze, 1989).

Perhaps the most important lesson to learn from this brief overview of the history of ideas on the causation of mental disorder is that each generation bases its theories of aetiology on the scientific approaches that are most active and plausible at the time. Sometimes psychological ideas prevail, sometimes neuropathological ones, and sometimes genetic ones. Throughout the centuries, however, observant clinicians have been aware of the complexity of the causes of psychiatric disorders, and have recognized that neither aetiology nor treatment should focus narrowly on the scientific ideas of the day. Instead, the approach should be broader, encompassing whatever psychological, social, and biological factors seem to be most important in the individual case. Modern psychiatrists are working in an era of rapid development of the neurosciences, but they need to keep the same broad clinical perspective of aetiology while assimilating any real scientific advances.

The contribution of scientific disciplines to psychiatric aetiology

The main groups of disciplines that have contributed to the knowledge of psychiatric aetiology are shown in Table 5.1. In this section each group is discussed in turn, and the following questions are asked:

• What sort of problem in psychiatric aetiology can be answered by each discipline?

• How, in general, does each discipline attempt to answer the questions?

• Are any particular difficulties encountered when applying its methods to psychiatric disorders?

Clinical descriptive studies

Before reviewing more elaborate scientific approaches to aetiology, attention is drawn to the continuing value of simple clinical investigations. Psychiatry was built on such studies. For example, the view that schizophrenia and the mood disorders are likely to have separate causes depends ultimately on the careful descriptive studies and follow-up enquiries carried out by earlier generations of psychiatrists.

Table 5.1 Scientific disciplines that contribute to psychiatric aetiology

Epidemiology |

Social sciences |

Experimental and clinical psychology |

Genetics |

Biochemical studies |

Pharmacology |

Endocrinology |

Physiology |

Neuropathology |

Anyone who doubts the value of clinical descriptive studies should read the paper by Aubrey Lewis on ‘melancholia’ (Lewis, 1934). This paper describes a detailed investigation of the symptoms and signs of 61 cases of severe depressive disorder. It provided the most complete account in the English language and it remains unsurpassed. It is an invaluable source of information about the clinical features of depressive disorders untreated by modern methods. Lewis’s careful observations drew attention to unsolved problems, including the nature of retardation, the relationship of depersonalization to affective changes, the presence of manic symptoms, and the validity of the classification of depressive disorders into reactive and endogenous groups. None of these problems has yet been solved completely, but the analysis by Lewis was important in focusing attention on them.

Although many opportunities for this kind of research have been taken already, it does not follow that clinical investigation is no longer worthwhile. For instance, the study by Judd et al. (2002) described in Chapter 6 (p. 126) is a recent example of how a clinical follow-up study can provide important insight into the aetiology of milder mood disorders in relation to bipolar disorder. Well-conducted clinical enquiries are likely to retain an important place in psychiatric research for many years to come.

Epidemiology

Epidemiology is the study of the distribution of a disease in space and time within a population, and of the factors that influence this distribution. Its concern is with disease in groups of people, not in the individual person.

Concepts and methods of epidemiology

The basic concept of epidemiology is that of rate, or the ratio of the number of instances to the numbers of people in a defined population. Instances can be episodes of illness, or people who are or have been ill. Rates may be computed on a particular occasion (point prevalence) or over a defined interval (period prevalence).

Other concepts include inception rate, which is based on the number of people who were healthy at the beginning of a defined period but became ill during it, and lifetime expectation or risk, which is based on an estimate of the number of people who could be expected to develop a particular illness in the course of their whole life. In cohort studies, a group of people are followed for a defined period of time in order to determine the onset of or change in some characteristic with or without previous exposure to a potentially important agent (e.g. lung cancer and smoking).

Three aspects of method are particularly important in epidemiology:

• defining the population at risk

• defining a case

• finding cases.

It is essential to define the population at risk accurately. Such a population can be all the people living in a limited area (e.g. a country, an island, or a catchment area), or a subgroup chosen by age, gender, or some other potentially important defining characteristic.

Defining a case is the central problem of psychiatric epidemiology. It is relatively easy to define a condition such as Down’s syndrome, but until recently the reliability of psychiatric diagnosis has not been satisfactory. The development of standardized techniques for defining, identifying, rating, and classifying mental disorders (see pp. 29–33) has greatly improved the reliability and validity of epidemiological studies.

Two methods are used for case finding. The first is to enumerate all cases known to medical or other agencies (declared cases). Hospital admission rates may give a fair indication of rates of major mental illnesses, but not, for example, of most mood or anxiety disorders. Moreover, hospital admission rates are influenced by many variables, such as the geographical accessibility of hospitals, attitudes of doctors, admission policies, and the law relating to compulsory admissions.

The second method is to search for both declared and undeclared cases in the community. In community surveys, the best technique is often to use two stages—preliminary screening to detect potential cases with a self-rated questionnaire such as the General Health Questionnaire (Goldberg, 1972), followed by detailed clinical examination of potential cases with a standardized psychiatric interview.

Aims of epidemiological enquiries

In psychiatry, epidemiology attempts to answer three main kinds of question:

• What is the prevalence of psychiatric disorder in a given population at risk?

• What are the clinical and social correlates of psychiatric disorder?

• What factors may be important in aetiology?

Prevalence can be estimated in community samples or among people attending general practitioners or hospital cases. Studies of prevalence in different locations, social groups, or social classes can contribute to aetiology. Studies of associations between a disorder and clinical and social variables can do the same, and may be useful for clinical practice. For example, epidemiological studies have shown that the risk of suicide is increased in elderly men with certain characteristics, such as living alone, misusing drugs or alcohol, suffering from physical or mental illness, and having a family history of suicide.

Causes in the environment

Epidemiological studies of aetiology have been concerned with predisposing and precipitating factors, and with the analysis of the personal and social correlates of mental illness. Among predisposing factors, the influence of heredity has been examined in studies of families, twins, and adopted people, as described below in the section on genetics. Other examples are the influence of maternal age on the risk of Down’s syndrome, and the psychological effects of parental loss during childhood. Studies of precipitating factors include life-events research, which is described below in the section on the social sciences.

Epidemiological approaches to aetiology can be illustrated by the results of studies of environmental correlates of mental disorders. For example, it has been apparent for many years that schizophrenia is more common in urban environments, particularly in disadvantaged inner-city areas. This finding could be of aetiological importance or it could be a consequence of the experience of schizophrenia with, for example, people in the early stages of illness seeking isolation. In a study of this question, van Os et al. (2003) confirmed that the prevalence of psychosis increased linearly with the degree of urbanicity (overall odds ratio, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.30–1.89). This significant effect remained after adjustment for factors such as age, gender, education level, parental psychiatric history, and country of birth.

As expected, there was in addition an independent and highly significant influence of a family history of psychosis on the risk of an individual developing psychosis (odds ratio, 4.59; 95% CI, 2.41–8.74). Further analysis showed that the effect of urbanicity on increasing the risk of psychosis was much greater in individuals with a family history of psychosis than in those without such a history. These findings suggest an important interaction between gene and environment, such that the adverse environmental effects of urbanicity are expressed particularly in individuals with a genetic predisposition to psychosis.

Social sciences

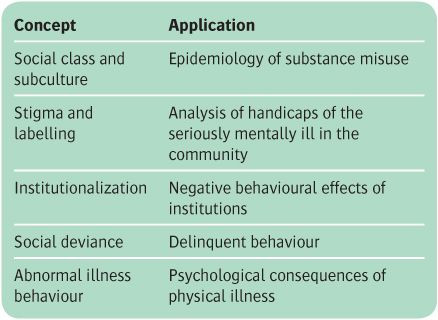

Many of the concepts used by sociologists are relevant to psychiatry (see Table 5.2). Unfortunately, some of these potentially fruitful ideas have been used uncritically—for example, in the suggestion that mental illness is no more than a label for socially deviant people, the so-called ‘myth of mental illness.’ This development points to the obvious need for sociological theories to be tested in the same way as other theories by collecting appropriate data.

Some of the concepts of sociology overlap with those of social psychology—for example, attribution theory, which deals with the way in which people interpret the causes of events in their lives, and ideas about self-esteem. An important part of research in sociology, namely the study of life events, uses epidemiological methods (see below).

Table 5.2 Some applications of social theory to psychiatry

Transcultural studies

Studies conducted in different societies help to make an important causal distinction. Biologically determined features of mental disorder are likely to be similar in different cultures, whereas psychologically and socially determined features are likely to be dissimilar. Thus the ‘core’ symptoms of schizophrenia have a similar incidence in people from widely different societies, which suggests that a common neurobiological abnormality is likely to be important in aetiology (see Chapter 11).

By contrast, depressive disorders have a wider range of prevalence. The Cross-National Collaborative Group (Weissman et al., 1996) found lifetime rates of depression ranging from 1.5% in Taiwan to 19% in Lebanon. In addition, there are variations in the clinical presentation of depressive states, with prominent somatic symptoms being more common in non-Western cultures. In all societies, however, sadness, joylessness, anxiety, and lack of energy are common symptoms (see Bhugra and Mastro-gianni, 2004).

The study of life events

Epidemiological methods have been used in social studies to examine associations between illness and certain kinds of events in a person’s life. In an early study, Wolff (1962) studied the morbidity of several hundred people over many years, and found that episodes of illness clustered at times of change in the person’s life. Holmes and Rahe (1967) attempted to improve on the highly subjective measures used by Wolff. They used a list of 41 kinds of life event (e.g. in the areas of work, residence, finance, and family relationships), and weighted each according to its apparent severity (e.g. 100 for the death of a spouse, and 13 for a spell of leave for a serviceman).

In later developments the study of the psychological impact of life events has been further improved in a number of ways.

• To reduce memory distortion, limits are set to the period over which events are to be recalled.

• Efforts are made to date the onset of the illness accurately.

• Attempts are made to exclude events that are not clearly independent of the illness (e.g. losing a job because of poor performance).

• Events are characterized in terms of their nature (e.g. losses or threats) as well as their severity.

• Data are collected with a semi-structured interview and rated reliably.

Although they are significant, life events taken in isolation may be less important than first appears to be the case. For example, in one study, events involving the loss or departure of a person from the immediate social field of the respondent (‘exit events’) were reported in 25% of patients with depressive disorders, but in only 5% of controls. This difference was significant at the 1% level and appears impressive, but Paykel (1978) questioned its real significance on the basis of the following calculation.

The incidence of depressive disorder is not accurately known, but if it is taken to be 2% for new cases over a 6-month period, a hypothetical population of 10 000 people would yield 200 new cases. If exit events occurred for 5% of people who did not become cases of depressive disorder, in the hypothetical population, exit events would occur for 490 of the 9800 people who were not new cases. Among the 200 new cases, exit events would occur for 25% (i.e. 50 people). Thus the total number of people experiencing exit events would be 490 plus 50, or 540, of whom only 50 (less than 1 in 10) would develop depressive disorders. Thus the greater part of the variance in determining depressive disorder must be attributed to something else. That is, life events trigger depression largely in predisposed individuals.

This idea leads us on to the consideration of vulnerability and protective factors (see below). However, at this point it is also worth noting that studies of genetic epidemiology have taken life events research a stage further by showing that the tendency to experience adverse life events is itself partly genetically determined. For example, individuals differ genetically in their liability to ‘select’ those environments that put them at relatively higher risk of experiencing adverse life events. Presumably this is one way in which the genetic vulnerability to depression may be expressed (see Kendler et al., 2004).

Vulnerability and protective factors

People may differ in their response to life events for three reasons. First, the same event may have different meanings for different people, according to their previous experience. For example, a family separation may be more stressful to an adult who has suffered separation in childhood. Thus adverse experiences that are remote in time from the adverse life event itself may predispose to the later development of psychiatric disorder.

The other reasons are that certain contemporary factors may increase vulnerability to life events or protect against them. Ideas about these last two factors derive largely from the work of Brown and Harris (1978), who found evidence that, among women, vulnerability factors include being responsible for the care of small children and being unemployed, while protection is conferred by having a confidant with whom problems can be shared. The idea of protective factors has been used to explain the observation that some people do not become ill even when they are exposed to severe adversities. Recent studies suggest that similar protective and vulnerability factors may also modify the response to life stress in other cultures. For example, in women living in an urban setting in Zimbabwe, the risk of depression following a severe adverse life event was substantially reduced by the presence of a supportive family network (Broadhead et al., 2001).

Causes in the family

It has been suggested that some mental disorders are an expression of emotional disorder within a whole family, not just a disorder in the person seeking treatment (the ‘identified patient’). Although family problems are common among people with psychiatric disorder, their general importance in aetiology is almost certainly overstated in this formulation, as emotional difficulties in other family members may be the result of the patient’s problems, rather than its cause. In addition, emotional difficulties in close relatives may result from shared genetic inheritance. For example, the parents of children with schizophrenia have an increased risk of schizotypal personality disorder (see p. 282). It seems more likely that family difficulties may modify the course of an established disorder. For example, high levels of ‘expressed emotion’ from family members increase the risk of relapse in patients with schizophrenia (see p. 285). However, in terms of aetiology, twin studies show that shared (family) environment is less important than shared genes in explaining familial clustering in most psychiatric phenotypes.

Migration

Moving to another country, or even to an unfamiliar part of the same country, is a life change that has been suggested as a cause of various kinds of mental disorder. A number of possible mechanisms have been identified:

• Selective migration. People in the early stages of an illness such as schizophrenia may migrate because of failing relationships in their country of origin.

• Process of migration. Events relating to the process of migration itself (e.g. physical and emotional trauma, prolonged waiting periods, exhaustion, and social deprivation and isolation) may cause several different kinds of stress-related disorder.

• Post-migration factors. Many factors come into play post migration which could influence the risk of developing mental illness. These include social adversity caused, for example, by racial discrimination and acculturation, in which the breakdown of traditional cultural structures results in loss of self-esteem and social support. Disparities between aspiration and achievement may also cause stress and depression. Finally, immigrants may be exposed to unfamiliar viruses, which could conceivably affect intrauterine development and predispose to psychiatric disorder in the next generation.

It is fairly well established that immigration is associated with higher rates of psychosis in several ethnic groups, but the mechanisms involved are unclear (see Chapter 11). The effects of immigration on other psychiatric disorders are less consistent, and some groups experience a relative improvement in mental health compared with their native populations. Clearly, refugees who have fled persecution are likely to have elevated rates of stress-related symptomatology, and many of them will meet the formal diagnostic criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder. However, it is important that such symptoms are interpreted sensitively in the context of the relevant cultural ways of dealing with trauma.

Experimental and clinical psychology

The psychological approach to psychiatric aetiology has a number of characteristic features:

• the idea of continuity between the normal and abnormal. This idea leads to investigations that attempt to explain psychiatric abnormalities in terms of processes that determine normal behaviour

• concern with the interaction between the person and their environment. The psychological approach differs from the social approach in being concerned less with environmental variables and more with the person’s ways of processing information that is coming from the external environment and from their own body

• an emphasis on factors that maintain abnormal behaviour. Psychologists are less likely to regard behavioural disorders as resulting from internal disease processes, and more likely to assume that persisting behaviour is maintained by abnormal coping mechanisms (e.g. by anxiety-reducing avoidance strategies).

Neuropsychology

Neuropsychological approaches share common ground with biological psychiatry in attempting to identify the neurobiological substrates for psychological phenomena. Various methodologies are employed, but the aim is to understand psychopathology in the context of brain science. Investigations may therefore involve animal experimental work or a range of human studies, including neurological patients with defined brain lesions and patients with psychiatric disorders.

For example, animal experimental models have shown that there is a crucial role for the amygdala in fear conditioning. Furthermore, because of its connections to the thalamus, the amygdala is activated by threatening stimuli and can produce autonomic fear responses before there is any conscious awareness of threat. LeDoux (1998) has related this circuitry to traumatic anxiety by proposing an imbalance between the implicit (unconscious) emotional memory system involving the thalamus and amygdala and the explicit (conscious) declarative memory system in the temporal lobe and hippocampus (see below).

In addition to animal experimental studies, neuropsychological investigations also involve different groups of human subjects. Valuable information may be gained from subjects who have suffered well-defined brain lesions. For example, patients with bilateral amygdala lesions can recognize the personal identity of faces, but not the facial expression of fear. This supports the notion that the amygdala is important in the processing of fear-related stimuli.

Current neuropsychological approaches also make extensive use of functional brain imaging techniques. This allows localization of the brain regions and neural circuitry involved in specific psychological processes, and facilitates comparisons between healthy subjects and patients who experience abnormalities in the processes concerned. For example, in a magnetic resonance imaging investigation it was found that when patients with depression were shown pictures of fearful facial expressions, they exhibited greater activation than controls in brain circuitry related to the processing of anxiety, including the amygdala. This increased activation was attenuated by treatment with antidepressant medication (Fu et al., 2004). This suggests that increased activity of the amygdala may play a role in the anxious preoccupations which are characteristic of depression, and that anti-depressants may act by decreasing amygdala function.

Information processing

The information theory approach to psychology proposes that the brain can be regarded as an information channel, which receives, filters, processes, and stores information from sense organs, and retrieves information from memory stores. This approach, which compares the brain to a computer, suggests useful ways of thinking about some of the abnormalities in psychiatric disorders. There are various mechanisms involved at different stages of information processing and therefore different points at which dysfunctional processing could give rise to psychiatric disorder. Two of these mechanisms are attention and memory, changes in which have been linked to psychiatric symptomatology.

Attention

Attention is viewed as an active process of selecting, from the mass of sensory input, the elements that are relevant to the processing that is being carried out at the time. There is evidence that attentional processes are disturbed in some psychiatric disorders. For example, anxious patients attend more than non-anxious controls to stimuli that contain elements of threat. This can be shown experimentally as a disruption of psychological performance where the task involves ignoring threat-related words. One example is the use of a modified Stroop test, where subjects have to name the colour of a background on which a word is written. When the word is a threatening one (e.g. ‘kill’), the latency taken to name the background colour is increased, and this increase is exaggerated in anxious subjects.

Subsequent studies have made two additional observations that are clinically important. First, the attentional bias in anxiety disorders is probably due to a failure to disengage attention from threat-related stimuli, rather than to excessive initial orientation towards them. Secondly, anxious subjects still produce greater responses to threat-related stimuli than controls, even when the stimuli are ‘masked’ so that they are received outside conscious awareness. Masking is achieved by presenting the stimulus for a very short time (less than 40 milliseconds), immediately followed by the longer presentation of another stimulus (the mask). The fact that masked stimuli elicit greater behavioural responses in anxious subjects suggests that the abnormal attentional mechanisms in anxiety involve the non-conscious threat-processing pathways associated with the amygdala (LeDoux, 1998). Although these findings are of interest, it is important to remember that they may in fact be a consequence of the anxiety disorder rather than a causal mechanism. However, even in the former case they could still play a role in maintaining symptomatology.

Memory

The information-processing model has been applied fruitfully to the study of memory. It suggests that there are different kinds of memory store, namely sensory stores in which sensory information is held for short periods while awaiting further processing, a short-term store in which information is held for only 20 seconds unless it is continually rehearsed, and a long-term store in which information is retained for long periods. There is a mechanism for retrieving information from this long-term store when required, and this mechanism could break down while memory traces are intact. This model has led to useful experiments. For example, patients with the amnestic syndrome (see p. 319) score better on memory tests that require recognition of previously encountered material than on tasks that require unprompted recall. This finding suggests a breakdown of information retrieval rather than of information storage.

It is well established that low mood facilitates recall of unhappy events. This can be demonstrated in healthy subjects undergoing a negative mood induction as well as depressed patients (Clark and Teasdale, 1982). Once again, it is not clear whether in depressed patients this phenomenon is a manifestation of depressed mood, or one of its causes. However, it is possible that it could play a role in maintaining the depressive state. More recent research has focused on the way that patients with mood disorders recall personal memories. For example, when asked to think of a specific event associated with the word ‘happy’, a depressed patient may give the response ‘when I used to go for long walks by myself’, which is a rather general reply. In contrast, a non-depressed person is more likely to respond quite specifically—for example, ‘when I went for a walk in Leighton Forest last Sunday with my family.’ This over-generalized style of memory recall is associated with a history of negative life events, and might also be linked to impaired problem-solving ability (Hermans et al., 2008).

As noted above, there is increasing interest in how explicit declarative and implicit emotional memories might be involved in the processing of traumatic events. It has been suggested that during highly traumatic experiences, explicit memory of the event is relatively poor whereas implicit (unconscious emotional memory) is vivid. This could give rise to the automatic intrusions and poor explicit memory that are seen in post-traumatic stress disorder (Amir et al., 2010).

Beliefs and expectations

The information-processing model also predicts that responses to information, including emotional responses, are determined by beliefs and expectations. This idea proposes that behaviour of all individuals is guided by their beliefs, and that psychopathology is associated with altered content of beliefs about the self and the world. Cognitive psychology assumes that such beliefs are organized into schemas. Schemas have important properties in relation to different kinds of psychopathology.

• They influence information processing, conscious thinking, emotion, and behaviour.

• Although not necessarily accessible to direct introspection, their content can usually be reconstructed in verbal terms (known as assumptions or beliefs).

• In patients with psychiatric disorders, these beliefs are dysfunctional, resistant to refutation, and play a part in the aetiology and maintenance of the disorder.

These ideas have been used in the development of cognitive therapy, where researchers aim to identify the dysfunctional beliefs associated with particular disorders and apply techniques that help the patient to re-evaluate and change them. For example, experimental work has shown that patients with panic disorder (see p. 197) have inaccurate expectations that sensory information about rapid heart action predicts an imminent heart attack. This expectation results in anxiety when the information is received, with the result that the heart rate accelerates further and a vicious circle of mounting anxiety is set up. Changing these expectations can alleviate panic attacks (see Chapter 9).

Ethology and evolutionary psychology

Many psychological studies involve quantitative observations of behaviour. In some of these investigations, use is made of methods that were originally developed in the related discipline of ethology. Complex behaviour is divided into simpler components and counted systematically. Regular sequences are noted as well as interactions between individuals (e.g. between a mother and her infant). Such methods have been used, for example, to study the effects of separating infant primates from their mothers, and to compare this primate behaviour with that of human infants separated in the same way.

More recent applications of ethology have used insights from the field of volutionary psychology to understand both normal and abnormal behaviour in an evolutionary context. This approach attempts to explain why various behaviours might have arisen in terms of evolutionary adaptation.

For example, because depressive states are ubiquitous in human societies, it is reasonable to ask what their adaptive value may be. One suggestion is that depression may reflect a form of subordination in animals who have lost rank in a social hierarchy. Rather than fighting a losing battle, the depressed individual withdraws and conserves their emotional resources for another day.

Such ideas are not readily testable experimentally, but can give rise to hypotheses concerning possible brain mechanisms. One theoretical difficulty is that psychiatric disorders often appear to represent maladaptive rather than adaptive behaviours. For example, Wolpert (1999) has drawn an analogy with cancer, in which the consequences of abnormal cell growth are clearly maladaptive and injurious to the individual. As cancer can be regarded as normal cell division ‘gone wrong’, so depression might be normal emotion (e.g. sadness) ‘gone wrong.’ From this viewpoint the question is not what is the adaptive value of the abnormal behaviour, but rather what is the adaptive value of the normal behaviour to which the abnormal state is related (for a review, see Varga, 2011).

Genetics

Most psychiatric disorders have a genetic contribution, and a significant amount of aetiological research is currently devoted to identifying the genes concerned, and the mechanisms by which they influence the risk of illness. The concepts, methods, and terminology of psychiatric genetics are complex, and will only be introduced briefly here. For more detailed coverage, the textbook by Owen et al. (2003) listed in the Further Reading section provides a useful starting point, and can be supplemented and updated by Thapar and McGuffin (2009) and Flint (2009).

The genetic contribution to psychiatric disorders

The first clue that a disorder has a genetic component usually comes from studying aggregation in families. In psychiatry, this is often complemented by adoption studies. However, it is twin studies that provide the most compelling evidence. Positive findings then provide the impetus to use techniques of molecular genetics to locate and identify the genes concerned.

Family studies

In family studies, the investigator determines the risk of a psychiatric condition among the relatives of affected individuals and compares it with the expected risk in the general population. The affected individuals are usually referred to as index cases or probands. Such studies require a sample that has been selected in a strictly defined way. Moreover, it is not sufficient to ascertain the current prevalence of a psychiatric condition among the relatives, because some of the population may go on to develop the condition later in life. For this reason, investigators use corrected figures known as expectancy rates (or morbid risks).

Family risk studies have been used extensively in psychiatry. Since families share environments as well as genes, these studies by themselves cannot clearly reveal the importance of genetic factors. However, by demonstrating that the disorder of interest shows familial clustering, they are a valuable first step, pointing to the need for other kinds of investigation.

Adoption studies

Adoption studies provide another useful means of separating genetic from environmental influences. The basic method is to compare rates of a disorder in biological relatives with those in adoptive relatives. Three main designs are used:

• adoptee study: the rate of disorder in the adopted-away children of an affected parent is compared with that in adopted-away children of healthy parents

• study of the adoptee’s family: the rate of disorder in the biological relatives of affected adoptees is compared with the rate in adopted relatives

• cross-fostering study: the rate of disorder is measured in adoptees who have affected biological parents but unaffected adoptive parents, and compared with the rate in adoptees who have healthy biological parents but affected adoptive parents.

Adoption studies are affected by a number of biases, such as the reasons why the child was adopted, the consequences of adoption itself, the non-random nature of the placement (i.e. efforts are made to match the characteristics of the child to those of the adoptive parents), and the effects on adoptive parents of raising a difficult child. They may also be limited by small sample sizes, especially as adoption becomes a rarer event in many countries. A more fundamental limitation is that adoption studies do not control for the prenatal environment, which may be important for disorders associated with intrauterine factors or birth complications. The value and limitations of adoption studies are perhaps best illustrated in schizophrenia research (see Chapter 11).

Twin studies

Twin studies are now the most important and widely used method for measuring the genetic contribution to a phenotype (an observable characteristic, such as a personality trait or a disorder). In twin studies the investigator seeks to separate genetic and environmental influences by comparing rates of concordance (i.e. where both co-twins have the same disorder) in uniovular (monozygotic, MZ) and binovular (dizygotic, DZ) twins (Kendler, 2001). If concordance for a psychiatric disorder is higher in MZ twins than in DZ twins, a genetic component is presumed; the greater the difference in concordance, the greater the heritability (see below). As well as showing the size of the genetic contribution, modern twin studies allow the environmental contribution to be divided into that which is unique to the individual (‘non-shared’) and that which reflects the common (‘shared’) environment experienced by the twins. This is usually done using a statistical approach called structural equation modelling.

Despite their key role in genetic epidemiology, the results of twin studies should not be accepted uncritically, as they make several assumptions, which are outlined in Box 5.2.

Heritability

Heritability is a measure of the extent to which a pheno-type is ‘genetic.’ More precisely, it refers to the proportion of the liability to the phenotype that is accounted for by additive genetic effects (Visscher et al., 2008). Recent estimates for common psychiatric disorders, based on population-based twin studies, are shown in Table 5.3 (see also Box 5.5). The data show that most psychiatric disorders—like most biological and behavioural traits—are heritable to a degree, and many show a substantial heritability.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree