Alzheimer Disease and Other Dementias

Neelum T. Aggarwal

Raj C. Shah

key points

Dementia is a common age-related condition with a prevalence of about 5% in persons over age 65 years and up to 50% in persons over the age of 85 years.

Alzheimer disease is the most frequent type of dementia in the United States and Europe, comprising approximately 60 to 80 percent of persons who present with dementing disorders. Other forms of dementia, such as Lewy Body disease, frontotemporal dementia, and vascular dementia, also are increasingly being recognized.

Facing increasing numbers of older patients with cognitive symptoms, primary care physicians need to have a practical approach for recognizing and managing Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias.

The goal of this chapter is to present a framework diagnosing individuals with cognitive concerns and developing a tailored care plan.

OVERVIEW

Dementia (or chronic loss of cognitive function) associated with old age was recognized in antiquity. For most of history, dementia of older persons was attributed to the effects of aging or to the effects of cerebral artherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries). In the early 20th century, Dr Alois Alzheimer presented the clinical history of a 54-year-old woman with a progressive dementia that he ascribed to the accumulation of senile plaques and tangles found on postmortem examination. Based on his case study, the term “Alzheimer disease” (AD) referred to a relatively uncommon progressive dementia in middle-aged persons. However, over the past 30 years, it has become apparent that most of the older people with dementia have the same condition described by Alzheimer almost 100 years ago.

Only a small proportion of people with dementia are managed in specialized dementia centers. Because physicians often do not look for or recognize the signs of dementia, many people with dementia remain undiagnosed. Timely diagnosis allows for the person with dementia to be a part of important care decision-making processes. It also permits early pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic intervention. Finally, it can prevent medical emergencies resulting from behavioral disturbances and other superimposed medical problems. Therefore, increased awareness of dementia offers neurologists and nonneurologists an opportunity to improve the lives of patients with dementia and their caregivers.

▪SPECIAL CLINICAL POINT: Up to two thirds of older people with dementia are not detected.

NORMAL AGING AND MILD COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT

Physicians often are faced with the dilemma of trying to determine the importance of complaints such as ‘senior moments” or “forgetfulness” voiced by their patients. In individuals who ultimately develop dementia and AD, one can presume that there is a gradual progression of an underlying process, which begins with “normal aging,” that can culminate into pathologically proven AD. Between the state of normal cognition and mild dementia is a zone often referred to as “mild cognitive impairment” (MCI). In the past, this zone has been referred to as “benign senescent forgetfulness,” “ageassociated memory impairment,” or “cognitive impairment no dementia.” In recent years, MCI has been increasingly used to describe individuals who typically have mild memory impairment noted on neuropsychological testing, with general cognitive functioning that is otherwise normal for age and normal activities of daily living. The clinical evaluation for subjects with suspected MCI is virtually identical to that for clinical AD, but may involve more detailed neuropsychological testing.

▪SPECIAL CLINICAL POINT: In persons with MCI, the mini-mental status examination (MMSE) scores often will appear normal (scores of 26 to 28). Yet, on neuropsychological examination, persons will show impairment on tests of verbal and nonverbal delayed recall, a finding that is often seen in early AD.

As characterization of MCI continues, research now has focused on identifying potential risk factors for the development of dementia and AD in those with MCI. Recent data suggest that persons who have been diagnosed with MCI are likely to be at an increased risk of developing AD and of cognitive decline. Further, they frequently have the pathology of AD, suggesting that MCI represents preclinical AD in many cases. The apolipoprotein e4 allele has been associated with the development of AD among persons with MCI in multiple studies, and some small samples have shown that elevated levels of tau in the cerebrospinal fluid may have the potential to predict the development of AD in MCI patients.

▪SPECIAL CLINICAL POINT: The rates of progression of MCI to AD are highly variable depending on the study; however, it is in the 10% to 15% per year range.

DEMENTIA

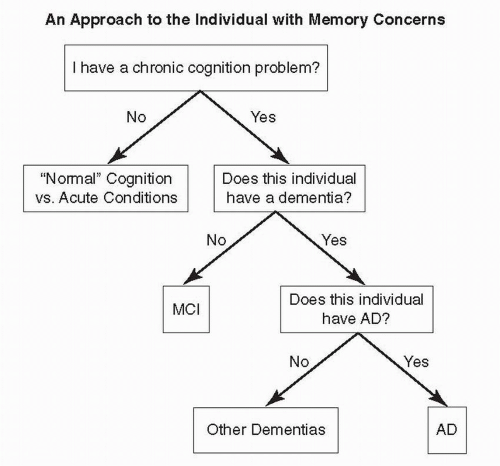

Dementia refers to acquired intellectual deterioration in an adult. Evaluating a person for dementia involves determining whether there has been a loss of cognition relative to a previous level of performance. The clinical evaluation for assessing memory complaints has four objectives: (a) to determine if the person has dementia; (b) if dementia is present, to determine whether its presentation and course are consistent with AD; (c) to assess evidence for any alternate diagnoses, especially if the presentation and course are atypical for AD; and (d) to evaluate evidence of other, coexisting, diseases that may contribute to the dementia, especially conditions that might respond to treatment. The section

titled “Differential Diagnosis of Primary Neurodegenerative Dementias” will provide details on important features in the patient’s history, key physical examination findings, and ancillary tests to conduct on an individual with memory concerns. An algorithm highlighting three decision point questions for clinically triaging a person with memory concerns is shown in Figure 14.1.

titled “Differential Diagnosis of Primary Neurodegenerative Dementias” will provide details on important features in the patient’s history, key physical examination findings, and ancillary tests to conduct on an individual with memory concerns. An algorithm highlighting three decision point questions for clinically triaging a person with memory concerns is shown in Figure 14.1.

Typically, evidence is obtained through the clinical history from a knowledgeable informant (a family member or close friend) and should be documented by mental status testing. When the clinical history is not available, test results from a single evaluation can be contrasted with the estimated premorbid level of ability based on the patient’s education and occupation. In some cases, formal neuropsychologic performance testing on two or more occasions over a period of 12 or more months may be necessary to document cognitive decline. For clinical purposes, loss of cognition should be sufficiently severe to interfere with an individual’s usual occupational or social activities and the cognitive deficit cannot be present in the setting of an altered sensorium such as in delirium or an acute confusional state.

Differential Diagnosis for Conditions Presenting with Cognitive Impairment

The differential diagnosis of dementia should emphasize common potentially treatable disorders that may cause or exacerbate cognitive impairment, which occur in the elderly. Reversible conditions including delirium, depression, structural conditions, and toxic or metabolic disorders, often are cited as potential causes of cognitive impairment. A thorough evaluation of each condition is justified for persons suspected of having dementia. If one of the conditions described below is identified as a potential cause of the cognitive impairment, appropriate treatment should be started. However, it is important to re-evaluate an individual

after treatment is completed to determine if cognitive difficulties have resolved. If resolution is not achieved fully, an underlying primary neurodegenerative cause for cognitive decline may also be present.

after treatment is completed to determine if cognitive difficulties have resolved. If resolution is not achieved fully, an underlying primary neurodegenerative cause for cognitive decline may also be present.

FIGURE 14.1 An algorithm for clinically triaging a person with memory concerns. MCI, mild cognitive impairment. AD, Alzheimer disease. |

Delirium Delirium differs from dementia by the onset and duration of cognitive impairment and by the level of consciousness. The onset of cognitive impairment in delirium typically is hours to days, and it lasts days to weeks. In addition, individuals often are either hyperalert or hypo-alert. However, in older persons, altered consciousness may be less evident. A delirium may be the initial manifestation of an underlying, unrecognized dementia. Thus, data suggest that delirium in the elderly may take many months to resolve or may not resolve at all. The occurrence of delirium in the hospitalized elderly has been associated with excess mortality.

Depression Loss of interest in hobbies and community activities, apathy, weight loss, and sleep disorders may be interpreted by the family as depression, although they actually may be the result of the dementia itself. Among the elderly, depression and dementia coexist and do not always present as two distinct entities. Although it is useful to ask the caregiver about symptoms suggesting dysphoric mood such as crying, complaining, and depression in the elderly may present with agitation or increased irritability. Depression may contribute to impairment of activities of daily living and rarely to the cognitive deficits. If impairment in activities of daily living exceeds what is expected for the severity of cognitive dysfunction, the possibility of a coexisting depression should be considered.

Structural Conditions Brain tumors rarely present with a degenerative dementia. When they do, there usually are other major focal findings and signs of increased intracranial pressure. Although rare, brain tumors in the “silent” areas of the brain may present only as a personality change and/or intellectual decline. Subtle focal findings usually can be demonstrated on the neurologic examination, but they occasionally are lacking. Similar comments may be applied to subdural hematomas, especially in the geriatric age group. Thus, some type of neuroimaging procedure remains warranted for all patients being evaluated for dementia.

No other syndrome causing dementia has generated such intense interest (and frustration) among neurologists as normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH). The classic syndrome consists of gait disturbance, dementia, and incontinence. However, this triad is also seen commonly in AD and other degenerative dementias.

▪SPECIAL CLINICAL POINT: NPH typically presents first as a gait disorder,and over time cognitive impairment and urinary incontinence can occur.

The onset can progress over months or years. The dementia is mild, often “subcortical” with slowing of thought and relative preservation of “cortical” features such as naming and language skills. Often there is no profound short-term (or episodic) memory deficit that distinguishes this dementia from AD. Brain scans typically demonstrate hydrocephalus with enlargement of ventricles out of proportion to sulci enlargement. Numerous studies have attempted to determine predictors of improvement following ventricular shunting, without much success. Perhaps the most useful piece of clinical information is the history of a reason for hydrocephalus (such as meningitis or subarachnoid hemorrhage from either a ruptured aneurysm or, more commonly, a previous traumatic head injury). Some patients with gait problems or dementia improve with cerebrospinal fluid shunting procedures; however, the insertion of a shunt is not a benign procedure, especially in geriatric patients. Although the diagnosis of NPH rarely, if ever, can be made with complete confidence, an etiology for the hydrocephalus should be sought prior to recommending shunting.

Toxic or Metabolic Disorders Drug toxicity is a common reversible cause of delirium in the elderly. Older persons may be more susceptible than younger persons to drug side effects on cognition. This is the result of many factors, including altered drug kinetics and use of multiple medications in older persons with several illnesses or complaints (polypharmacy). Clinicians also should be alert to the possibility of drug side effects further impairing cognition in persons with preexisting cognitive impairment. A typical presentation is the rapid worsening of dementia following the administration of a new drug (or following the reinstitution of a previous medication that the patient has not taken for some time), with or without altered level of consciousness.

▪SPECIAL CLINICAL POINT: Psychotropic (including neuroleptic), sedative-hypnotic, anticholinergic, and antihistaminic medications are common agents associated with cognitive impairment.

Hypothyroidism has been recognized for many years as being associated with altered mental state, although it is currently quite rare in the United States. Similar cases are seen with disorders of calcium metabolism, especially hypercalcemia, and also with an electrolyte imbalance. Chronic liver and renal diseases frequently are associated with an altered mental state; however, it is unusual for these diseases to be present without prominent manifestations of the primary illnesses. Finally, Korsakoff syndrome, a result of thiamine deficiency, also can present with an amnestic syndrome mimicking a dementia. It classically develops in the wake of an acute Wernicke encephalopathy with confusion, ophthalmoplegia, and ataxia. However, many patients with Korsakoff syndrome do not present with a Wernicke encephalopathy. Although alcoholism is the most frequent setting for this syndrome in developed countries, it also may be associated with other conditions leading to nutritional deficiency, including starvation, malnutrition, protracted vomiting, and gastric resection. It also can be precipitated by administration of carbohydrates to patients with marginal thiamine stores.

Cognitive impairment is among the most common neurologic manifestations of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and may precede the development of other signs of infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Persons with AIDS dementia complex present with forgetfulness and poor attention, generally over several months with the memory impairment significantly less striking than that seen in AD. Chronic meningitis, especially cryptococcal meningitis, also can present as dementia, although there are almost always other associated signs and symptoms. The same can be said for neurosyphilis. Brain abscesses, like brain tumors, can present solely with dementia, although focal findings are usually present.

Differential Diagnosis of Primary Neurodegenerative Dementias

Once the conditions presenting with cognitive impairment have been ruled out, the clinician then must determine the underlying nature of the dementia. It is at this time, referrals sometimes are made to a neurologist, as diagnosing of the exact neurodegenerative cause of a dementia may be problematic.

Generally speaking, if an elderly person presents with a gradual progression of a memory disorder, which is now advanced to involve other nonmemory cognitive domains and these changes have affected daily functioning, AD is the most likely diagnosis. Vascular dementia (VaD) can involve abrupt changes in cognition if large vessels are affected, or can be present insidiously if subcortical ischemia is responsible for the change in function. In subjects with parkinsonism, hallucinations, and wide fluctuations in behavior, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) might be more likely than AD. Alternatively, if the initial presentation is one of the changes in personality or behavior instead of memory, a frontotemporal dementia (FTD) should be considered. Finally, if the time course

of the dementia is relatively rapid over months and the clinical features include psychiatric symptoms and motor function abnormalities, a prion disorder such as Creutzfeld-Jakob disease (CJD) should be considered.

of the dementia is relatively rapid over months and the clinical features include psychiatric symptoms and motor function abnormalities, a prion disorder such as Creutzfeld-Jakob disease (CJD) should be considered.

Alzheimer Disease In 2000, it was estimated that there were approximately 4.5 million individuals with AD in the United States and this number has been projected to increase to 14 million by 2050. Prevalence estimates suggest that AD affects about 10% of persons over the age of 65, making it one of the most common chronic diseases of the elderly. The occurrence of AD is strongly related to age, with the incidence doubling every 5 years after the age of 65.

▪SPECIAL CLINICAL POINT: From the ages 65 to 85, the prevalence of AD doubles approximately every 5 years.

Other than age, there are few well-documented risk factors for AD. There is some evidence that women may be more likely to develop the disease than men. However, this observation appears to be attributed, in large part, to the fact that women live longer than men. Years of formal education have been associated with a reduced risk of disease in many, although not all studies. The mechanism linking education to risk of disease is unclear, but recent evidence suggests that participation in cognitively stimulating activities also reduces the risk of disease.

The first-degree relative appears to have a slightly greater risk of inheriting disease. In rare families, however, AD is inherited as an autosomal dominant disease in which half of the family members are affected. In these families, the disease has been linked to mutations on one of three different chromosomes: 21, 14, and 1 and often age of onset is very young (<65 years). The majority of cases of AD are “late onset” and in some of these cases, chromosome 19 has been implicated. Chromosome 19 is thought to code for the apolipoprotein E alleles. The presence of one apolipoprotein E e4 allele approximately doubles an individual’s risk of developing AD, and the risk is even higher among those homozygous for the allele. By contrast, the apolipoprotein E e2 allele appears to lower risk of the disease. The mechanism whereby this allele causes the disease is unknown, but recent data suggest that it increases the deposition of AD pathology.

▪SPECIAL CLINICAL POINT: Familial autosomal dominant cases comprise 5% to 10% of all the cases with AD.

Clinical Symptoms

▪SPECIAL CLINICAL POINT: The most common initial sign of AD is difficulty with episodic memory (the ability to learn new information). Old memories are often accurate and intact until the mid to later stages of the disease.

The clinical history should focus on the temporal relationship between the loss of different cognitive abilities and the development of behavioral disturbances and impairment of motor abilities. At the onset, this disease may be almost imperceptible, but it typically will progress to become a more serious problem in a few years’ time. The family will report that the patient frequently repeats himself or herself. He or she leaves important tasks undone, such as bills unpaid and appointments not kept. After the memory disorder becomes apparent, the family will notice other disorders of cognition. Confusion in following directions also can be a common earlier symptom. If the person is driving a car, he or she may get lost or “turned around” (an event that frequently precipitates the first evaluation by a physician), have an increase in minor “fender benders,” or use poor judgment while driving. Frightening lapses of memory, such as leaving on a gas stove, also may occur.

As the disease progresses, the person may have difficulty in remembering simple words or names and may be unable to participate in normal conversation. Often family members comment that the individual has become a “listener” instead of actively participating in conversations. Reading and writing also will be impaired, as will

simple activities of daily living, such as bathing and dressing.

simple activities of daily living, such as bathing and dressing.

Agitation, hallucination, delusions, and even violent outbursts may be seen at any time during the course of the illness. Previous personality traits may be exaggerated or may be obscured completely by new behavior patterns. Changes in sleep-wake patterns also may disrupt normal living patterns. These types of symptoms are particularly difficult for the family and place a great burden on the caregiver. Parkinsonian signs such as unsteady gait and slowed movements are common.

▪SPECIAL CLINICAL POINT: A general physical decline is not seen until the latest stages of the illness. If decline occurs rapidly, which is associated with a change in gait, parkinsonian signs, or weakness, other dementing illnesses need to be considered (Fig. 14.1).

Incontinence may be seen at any time and initially may reflect the patient’s inability to find the bathroom. As the illness progresses, there seems to be a true loss of bladder control and, ultimately, a loss of bowel function. Inability to walk is also a common occurrence seen at the late stages of the illness. Seizures and an inability or unwillingness to eat also may occur in the later stages of AD.

The typical history in AD is a gradually progressive dementia over several years. The average patient with AD survives about a decade from the time of diagnosis, although the variation may be from a few years to 20 years. There may be plateau periods during which deterioration is not obvious; however, a lengthy plateau would be unusual. There is no clear evidence that the age of onset determines the natural history. However, younger patients generally tend to have more speech disorders as the illness progresses. Older patients are more prone to age-related medical problems associated with morbidity and mortality.

Neurologic Examination Formal, standardized assessment of cognition is required to make a diagnosis of dementia and AD. Wide ranges of measures are available for this purpose. Several brief measures (e.g., the MMSE and the blessed orientation, memory concentration test) are suitable for use at the bedside or in the physician’s office. Although they may help distinguish persons with dementia from persons without dementia, they are less effective in distinguishing AD from other dementias. In these cases, full neuropsychological testing is recommended.

In the office or hospital, routine mental status testing should include checking the person’s orientation by asking for his or her full name, the day of the week, the day of the month, the month and the year, where he or she is, and also his or her age and date of birth. Show the individual four or five objects and then ask him or her to name them twice (e.g., a coin, a safety pin, keys, and a comb). Tell the person that you will ask him or her to recall the objects in a few minutes. Then check the individual’s knowledge of common events by asking for the names of well-known public figures (e.g., the president, governor, or mayor). Ask the person to repeat some numbers (the typical patient can remember six numbers forward and three or four backward) and then have him or her do some simple calculations (e.g., multiplication, addition, and serial sevens). Have the individual to repeat a simple phrase, to follow a two-step direction (e.g., point to the ceiling, then point to the floor), and to do something with his right hand and then his left hand (e.g., make a fist with your left hand, followed by salute with your right hand). Ask the individual to write his or her name, to write a brief phrase to dictation (e.g., today is Monday), and then to draw something (usually a clock). Also, ask the person to read a simple phrase. Finally, have the patient recall the four or five objects that you showed him or her previously. This mental status test can be administered in a few minutes and should be part of the routine clinical evaluation of all older persons. Recommended educationadjusted cutoffs have been developed for the MMSE and the results can serve as guidelines

to direct further evaluation, and also provide valuable screening information.

to direct further evaluation, and also provide valuable screening information.

▪SPECIAL CLINICAL POINT: To make a diagnosis of dementia, a deficit should exist in more than one area of cognition. Patients with early AD may have profound memory problems with only mild deficits in other aspects of cognition. As the disease progresses, however, language and other aspects of cognitive dysfunction typically become more obvious.

The most important function of the neurologic examination in evaluating persons with dementia is in diagnosing conditions other than AD. The general physical examination and neurologic examination (excluding the mental status testing) is usually normal in AD. Minor parkinsonian features, myoclonic jerks, frontal lobe signs (grasp reflex, snout and glabellar signs), and similar abnormalities occasionally may be seen on examination, especially later in the course of the illness. However, these features noted in persons with mild memory problems should alert the physician of a diagnosis other than, or perhaps in addition to, AD. If a person has parkinsonian signs, changes in gait and tone suggestive of rigidity in addition to memory complaints, the possibility of DLB exists. If a person has limb weakness, a visual field cut, or asymmetric reflexes, one could consider VaD or a mixed dementia (AD/VaD). Myoclonic jerks in addition to unsteady gait could signify a rapidly progressive dementia such as CJD.

Ancillary Tests

▪SPECIAL CLINICAL POINT: Currently there is no reliable diagnostic test for AD.

The purpose of laboratory testing is to identify other conditions that might cause or exacerbate dementia and include a brain scan and blood tests (Table 14.1). The use of lumbar puncture in the routine evaluation of elderly patients for dementia or AD is not recommended. However, if the clinical picture is associated with an acute change in mental status, nuchal rigidity, or fever, a lumbar puncture should be done to rule out a possible infectious etiology for the cognitive impairment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree