Chapter 98 An Approach for Treatment of Complex Adult Spinal Deformity

The range of normal for cervical lordosis, thoracic kyphosis, and lumbar lordosis is quite variable.1–3 Varying degrees of scoliosis can be tolerated depending on many other factors. As a result, spinal balance apparently is more important in terms of symptoms and progression than the magnitude of scoliosis or kyphosis. A review by Kuntz et al.1 showed that there is only a narrow range of spinal balance and that this is highly conserved.

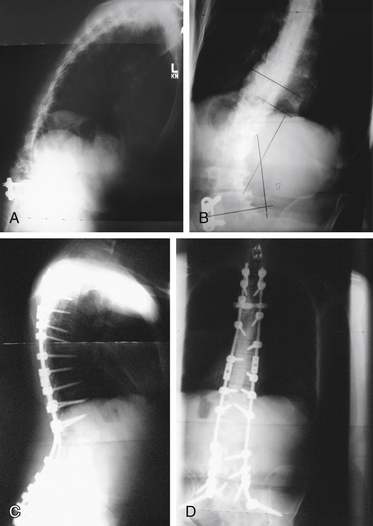

Clinically, spinal balance can be assessed by examining the head position of a standing patient in relation to the pelvis. In the lateral view, a plumb line from the ear canal should pass through or behind the greater trochanter. In the anteroposterior view, a plumb line from the inion should pass between the posterior superior iliac spines. Radiographically on a long cassette film, one can use either the C7 vertebral body or the odontoid as the starting point for a plumb line. Use of the odontoid as a marker allows assessment of cervical deformity in overall spinal balance. A plumb line from the odontoid should pass dorsal to the center of rotation of the hip in the lateral plane and should fall between the medial borders of the S1 pedicle in the anteroposterior plane. A plumb line from the C7 vertebral body should pass through the L5-S1 disc space. Figure 98-1 shows preoperative anteroposterior (see Fig. 98-1A) and lateral (see Fig. 98-1B) views of a patient with decompensated kyphoscoliosis with loss of both sagittal and coronal balance. Postoperative views of the same patient show restoration of balance (see Figs. 98-1C and D).

Define the Problem

Although it may seem simplistic, it is important to begin the process by defining the problem. In contrast to idiopathic adolescent scoliosis, in which the predominant focus is on the magnitude and progression of the deformity, there are more factors to consider in adult deformity. One key clinical difference in adult deformity is that adults generally seek treatment for the symptoms of the deformity rather than the deformity itself.4 As a result, the deformity is viewed within the context of the symptoms it produces. In addition, comorbidities need to be considered. In many cases, the patient will already have had other spine procedures.

The physical examination should include a detailed neurologic examination. Examination of spinal alignment and balance is important. Loss of sagittal and coronal balance is associated with increased symptoms and seems to have a higher risk of progression.5–7

In patients in whom surgery is being considered and comorbidities are present, general and specialty medical consultation for preoperative optimization should be used.8 Nutritional and bone health status are often overlooked in the workup and can have significant effects on outcome.9–12 Bone mineral density testing can help to assess bone health, although the presence of degenerative changes in the spine may artificially increase bone mineral density of the spine.13,14 Vitamin D testing and supplementation in the preoperative period should be considered, especially in regions or cultures where there is little direct sun exposure.15,16 In large-magnitude thoracic deformities, pulmonary function testing should be done for risk assessment.17

Goals

Prevention of progression is a common goal in treatment of deformity. In adult deformity, progression is unpredictable for many conditions, and progression of symptoms may or may not correlate with progression of deformity.18–20 As a result, prevention of progression is an uncommon indication for treatment after skeletal maturity.21–23

Generally, the goals of surgical treatment are to relieve compression of neural elements, stabilize instabilities, and correct and maintain the correction of the deformity. These goals need to be accomplished while minimizing risk in the short term and the long term. A primary end result of deformity treatment should be the restoration of sagittal and coronal balance. Outcome studies have shown weak, if any, correlation between correction of the Cobb angle and outcome but have shown clear correlation with spinal balance and outcome.6,7,24–27

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is common in patients with spinal deformity. It may be associated with vertebral fractures leading to increased deformity.21,28 It also may have an effect on outcome of surgery.11,29 Although osteoporosis does not affect bone healing, it does affect the holding power of spine instrumentation.30–32 For this reason, assessment of osteoporosis is an important step when considering surgery. Although there is no quoted level of bone density beyond which surgery is not an option, the risks of failure increase with higher degrees of bone loss. Preoperative optimization of bone health with vitamin D testing and supplementation as required and pretreatment with teriparatide have been advocated,16 but no studies have looked at outcomes of these interventions. Animal studies have suggested that teriparatide may improve healing of fusions.33,34

Options

Decompression Alone

In patients with a stable balanced spine with isolated radiculopathy, one option may be to consider an isolated decompression. Generally, compressive pathology occurs on the concavity of the deformity.35 If a single level can be identified either on the basis of clinical symptoms or with nerve root blocks, an isolated decompression may be a reasonable option. There is a risk that decompression may exacerbate deformity in these patients. Previous studies showed that the results of decompression alone in the presence of scoliosis may not be as good as decompression in a normally aligned spine.36–38 Many of these studies were done with more extensive decompression than would be done at the present time. Decompression alone is not an option in the presence of a rotatory subluxation or spondylolisthesis at the apex of the deformity. Anecdotally, decompressions of a keyhole or laminotomy type are associated with a lower risk of progression of deformity.39,40 This option may be particularly good in elderly patients with an isolated radiculopathy and relatively minimal axial back pain.

Limited Fusion

In many patients, symptoms can be isolated to a single level of pathology. An example would be a degenerative spondylolisthesis and a degenerative scoliosis. In these patients, it may be reasonable to treat only the symptomatic level. This is a controversial treatment. In a more recent study, reasonably good results were obtained with single-level fusion for degenerative spondylolisthesis in degenerative scoliosis. A few patients needed further surgery, and few if any had progression of deformity.41 Some authors have criticized this technique as having an unacceptably high rate of failure.42 However, there are no controlled trials comparing it with more extensive fusion; the literature contains few articles.43,44

One more recent trial45 looked at surgeons whose practice contained more than 50% deformity cases and showed that these surgeons were more likely to perform fusion of more levels than surgeons whose practice contained less than 50% deformity cases. The authors implied that the surgeons with more deformity cases were more likely to select a correct course; however, there was no clinical correlation in this study. It is perhaps equally valid to suggest that the surgeons with more deformity cases were more likely to perform fusion of excess levels.

Instrumented Correction and Fusion

In most cases, pedicle screw instrumentation is the mainstay of instrumented fusion. Pedicle screws allow better correction of most deformities.46–50 Pedicle screws are extremely versatile and have excellent holding power. They can exert or resist forces in multiple planes. Pedicle screws tend to be weakest in pull-out.51 As a result of their versatility, pedicle screws have become the main type of instrumentation used. Hooks and wires are less commonly used because they are more technically demanding and less versatile. Hooks and wires are relatively strong in pull-out but need intact posterior elements.

Obtaining solid biologic fusion is of utmost importance in the long-term. Fusion can be achieved through interbody, dorsal, or dorsolateral fusion. Interbody techniques generally have a higher fusion rate.52–54 In the lumbar spine, dorsolateral fusion is biomechanically superior and more effective than laminar onlay fusion.55 In the thoracic spine, dorsal fusion is more typically performed. The biology of fusion, choice of bone graft or bone graft substitute, and use of extenders are discussed elsewhere. In complex surgery with the high risk of fusion failure, the choice of bone graft and bone graft substitutes is of great importance. The use of bone morphogenetic protein in deformity seems to lead to significantly higher fusion rates. Limited evidence suggests that it is cost-effective in this indication.56–58

Selection of rostral and caudal levels is the first step in determining an operative plan. Generally, the construct should begin and end at a neutral vertebra in both the sagittal and the coronal planes. In complex or degenerative deformities, it is often more difficult to determine these levels than in an idiopathic scoliosis. The presence significant disc degeneration or instability below a neutral vertebra would generally necessitate extension of the fusion beyond this.59,60 Perhaps the most controversial question is whether or not to end a fusion at the L5 vertebra. Numerous studies have been performed and reached conflicting results.61–65

A series of studies by Lenke et al.61,62 looked at this question and concluded that if the L5-S1 disc is relatively normal on MRI and the L5 vertebral body does not have an oblique takeoff, preserving the L5-S1 motion segment is a reasonable option. In these patients, the incidence of repeat surgery to fuse the 5/1 level was lower than the incidence of repeat surgery for pseudarthrosis. In the presence of significant L5-S1 disc degeneration or oblique takeoff or instability at L5-S1, the incidence of repeat surgery to fuse the 5/1 level was higher than the incidence of surgery for pseudarthrosis.

Numerous factors must be looked at in considering the upper stop point of the construct. The thoracolumbar junction represents a transition from the mobile lumbar spine to the stiffer thoracic spine. Constructs extending up from the sacrum to the lumbosacral junction can create a stress riser if stopped at the junction. Typically, it has been considered acceptable to stop such a construct at L2, but constructs longer than this should extend to T1059,60,66,67; however, a more recent study has called this into question. In this study, there seemed to be no clearly defined level at which the risk of subsequent surgery was lessened.66 In deciding to stop in the lower thoracic spine, one must also consider whether this stop point is at the apex of the thoracic kyphosis. In patients in whom a fusion stops at the apex of the thoracic kyphosis, there is significant risk of proximal junctional kyphosis. It may be preferable in these patients to extend the construct up into the upper thoracic spine, typically T4 or T5.59,60

Long fusion constructs to the sacrum have a high incidence of failure because of pseudarthrosis at L5-S1. This pseudarthrosis is due to numerous biomechanical and anatomic factors. The S1 pedicle is more cancellous and has a short anteroposterior diameter, and the holding power of S1 pedicle screws is less than at other levels. In addition, forces at this level are magnified because of the relatively large lever arm exerted by the pelvis.65,69 Many strategies have been suggested to increase the fusion right at L5-S1. Primary among these strategies is the use of interbody fusion through either a ventral or a dorsal approach.65 This strategy has been shown to decrease pseudarthrosis.

More recent studies have assessed anterior lumbar interbody fusion and compared it with posterior lumbar interbody fusion or transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. None of these techniques showed clear superiority in these studies.68–71 McCord et al.72 analyzed alternative fixation techniques at the lumbosacral junction; this study led to the concept of the pivot point, which is the region of the dorsal aspect of the anulus fibrosus at L5-S1. Fixation at the lumbosacral junction should extend ventral to this pivot point to provide increased stability. Sacral alar screws, S2 screws, iliac bars and screws, and iliosacral screws have been suggested for this procedure. Biomechanical studies showed increased rigidity with the use of iliac or sacroiliac screws, and clinical studies suggested that these two fixation types are superior to sacral alar or S2 screws.70–77 In a longitudinal series by Kostuik and Musha,65 pseudarthrosis rates were decreased from 83% to 3% by the use of interbody fusion and iliac fixation.

Many authors have advocated increasing deformity correction through the use of anterior releases and fusions.78,79 It is believed that this approach increases correction and increases the fusion rate. However, more recent studies have called this into question.80–82 With the use of segmental pedicle screw fixation and alternative release techniques, equivalent deformity correction can be obtained through purely dorsal procedures without the morbidity83 of an anterior release. These studies compared more traditional open anterior release techniques. With the advent of new or less invasive procedures and the use of interbody fusions through a direct lateral approach, the morbidity of anterior releases may be significantly less. Such minimal access lateral approaches and fusion techniques have been shown to give good correction, high fusion rates, and reasonably good clinical results.84–86 In the author’s practice, these techniques have replaced traditional open releases and fusions. The use of these techniques at the L4-5 level should be considered cautiously. The anatomic corridor is small,87,88 and there is a relatively high rate of L3 neurapraxia.86 The author no longer uses minimal access lateral techniques for the L4-5 level.

Instrumentation in Osteoporosis

The presence of osteoporosis increases the failure rate of instrumented constructs in deformity surgery. Osteoporosis compromises the holding power of the implants leading to this increased failure rate. Numerous strategies have been mediated to lessen this failure risk, and Hu29 summarized them well in a review article. Essentially, these strategies all are methods of dispersing or decreasing forces across the construct. Increasing the number of fixation points decreases the stress on each element of the construct. Cement augmentation of pedicle screws has been shown to increase their pull-out resistance. Generally, it is unnecessary to perform cement augmentation of all fixation points; only the points at the ends of the construct need to be reinforced with cement. There is relatively more loss of cancellous than cortical bone in osteoporosis, and fixation that uses cortical bone is relatively stronger. As a result, laminar hooks may be a good option in a kyphosis construct, which is likely to fail in pull-out. If correction can be obtained through osteotomies or releases, loads on the hardware are more likely to be neutral, and the construct is less susceptible to hardware failure.12,29,89,90

Osteoporosis has been considered a relative contraindication to the use of interbody fusions. Biomechanical studies by Cunningham and Polly91 showed that use of interbody fusion increases the strength and rigidity of constructs. Interbody grafts or cages placed asymmetrically can be used to obtain correction, allowing the hardware to be in neutral and decreasing the risk of hardware failure.92

Interspinous Spacers

Interspinous spacers such as the X-Stop (Medtronic, Memphis, TN) are indicated for treatment of spinal stenosis in the absence of deformity. In the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) studies, scoliosis was an exclusion criterion. It has been suggested that these spacers may be used in an off-label manner for the treatment of stenotic symptoms in the presence of deformity.93 The author has used interspinous spacers in rare cases of patients with severe medical comorbidities and significant deformity who would not tolerate traditional surgery. The results have been mixed, but there have been few complications. Further studies are warranted.

Osteotomies

The simplest osteotomies to perform are facet resection osteotomies as described by Ponte or Smith-Petersen. There is confusion as to nomenclature of these osteotomies. Smith-Petersen et al.94 described a procedure where the facet was resected and the disc released leading to a pivot at the dorsal corner of the vertebral body, causing closure of the osteotomy dorsally and extension through the disc space ventrally. This procedure was originally described in ankylosing spondylitis. The more common facet resection and closure through a mobile disc was first described by Wilson and Turkell95 but has been widely attributed to Ponte.96 For clarity, the author uses facet resection osteotomy.

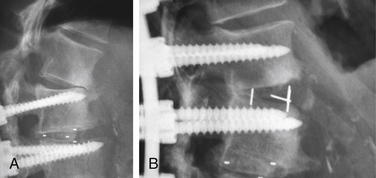

These osteotomies can be used anywhere there is a mobile disc. Correction of 5 to 10 degrees of kyphosis can readily be obtained, and multiple levels can be used.97,98 Some coronal correction can be obtained as well. Facet resections can also be used to increase the correction of the coronal deformity. A facet resection osteotomy augmented by an interbody fusion can increase the amount of correction obtained through this technique. An example is shown in Figure 98-2.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree