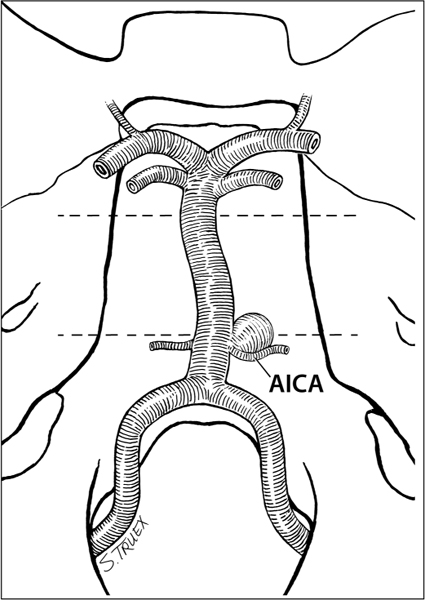

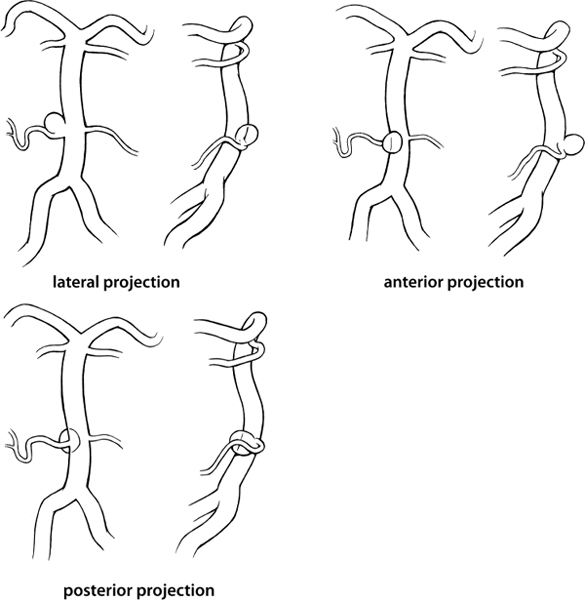

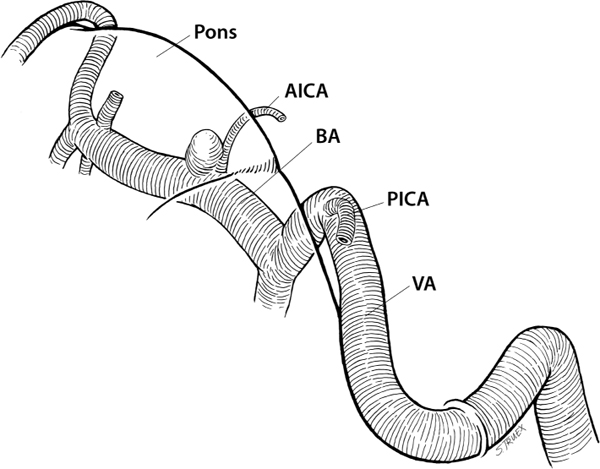

11 These aneurysms are infrequently encountered, even in a busy cerebrovascular practice, and represent the rarest aneurysm location dealt with in this book. Because of their rarity and their relative ease of endovascular access, increasingly they are initially referred for endovascular management, with direct surgery being reserved for the small number failing this approach. Furthermore, their location is not one routinely visited by neurosurgeons in the treatment of other disease processes, making anatomical unfamiliarity an additional deterrent to their surgical management. Aneurysms of the basilar artery at the origin of its anterior inferior cerebellar branch generally lie in the anatomical midline near the junction of the middle and inferior thirds of the clivus (Fig. 11.1). Depending on the anatomical vagaries of the parent vessel, they have been reported to arise as low as the basion and as distally as the tentorial incisura, making an exact understanding of the location of the lesion in question perhaps the most critical single issue in consideration of their treatment. The most consistent neuroanatomical localizer for the anterior-inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) origin is the sixth cranial nerve, which—reliably—lies slightly inferior and lateral to the AICA’s emergence from the parent artery. These lesions share with aneurysms of the posterior-inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) and the superior cerebellar artery (SCA) the propensity for involving a portion of the branch artery in their neck; coupled with the small size of the AICA, this may make effective clip placement difficult without endangering the patency of the AICA. Fig. 11.1 Anatomical configuration of the basilar artery. Fortuitously, almost all of these aneurysms in our experience have projected laterally or anterolaterally, although in Drake’s far larger series a significant minority projected either directly anteriorly or posteriorly into the underlying brain stem (Fig. 11.2). The most common projection routinely brings the dome of the lesion into close proximity with the sixth nerve, which not infrequently (especially following subarachnoid hemorrhage) is tightly bound to the fundus by a tenacious layer of dense arachnoid. Fig. 11.2 Projections of proximal basilar artery aneurysms. Historically, these lesions have been approached from almost every imaginable route of access, including transoral transclival exposures; this persistent variety is a testimony to the difficulties associated with their safe, atraumatic exposure and to the ongoing absence of a single optimal operative approach. As already mentioned, a critical issue is the exact location of the lesion under consideration, with aneurysms located very distally being relatively easily exposed by either a presigmoid transtentorial approach or, less commonly, a subtemporal transtentorial route as described by Drake. The low-lying aneurysms, which lie along the inferior third of the clivus, can be easily approached via the far lateral, transcondylar exposure popularized by Heros and described in Chapter 9 dealing with aneurysms of the PICA origin. Unfortunately, the most common location of AICA aneurysms in our personal experience has been in the relative “no man’s land” at the extremes of these two exposures (Fig. 11.3). There is just no easy way to get there, and given that fact, we have been most satisfied with pushing the superior limits of the far lateral exposure as opposed to working inferiorly through a presigmoid approach. The benefits of this choice, which may be purely speculative, include a broader superficial exposure (making easier access for two instruments), earlier proximal control, avoidance of early exposure of the aneurysm dome (we always approach from the side of the lesion), and what seems to be more latitude in the potential directions of clip application. The recognized negatives of this choice involve a greater operative depth, a more oblique approach, greater necessity to manipulate cranial nerves VII and VIII, as well as greater possibility of postoperative lower cranial nerve palsies and more difficult access to distal basilar control. Fig. 11.3 Relation of proximal basilar artery aneurysms to brainstem. The routine far lateral suboccipital approach described earlier is used, and despite the height of the target aneurysm, a hemilaminectomy of C1 is done, and the foramen magnum is opened widely. These two components of the exposure minimize the degree of cerebellar retraction and of lower cranial nerve manipulation and facilitate both early demonstration of both vertebral arteries and later dissection through the veil of arachnoid covering cranial nerves VII through XI. The major hindrance in the dissection process is the interposition of the lower cranial nerves (VII–XI) between the surgeon and the proximal basilar artery (Fig. 11.4

Aneurysms of the Proximal Basilar Artery

General

Anatomy

Projection

Surgical Approaches

Craniotomy

Dissection

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree