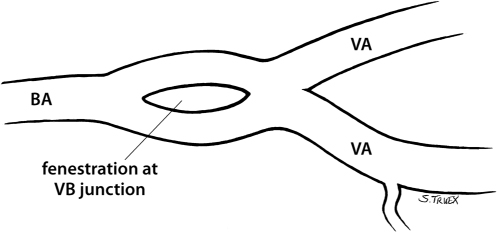

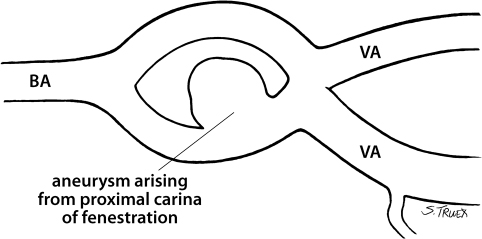

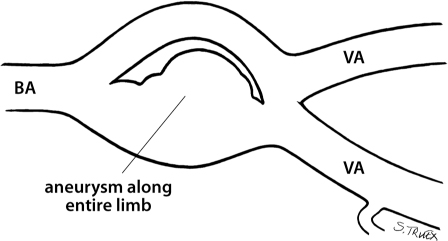

10 There are no more difficult intracranial aneurysms to treat surgically than those that occur at the confluence of the vertebral arteries. These lesions are rare, frequently present with subarachnoid hemorrhage, and often have unique anatomical relationships with the parent artery (ies). Located in the anatomical midline, shrouded by the brain stem and cranial nerves, and only approachable via a deep, narrow, and oblique exposure, they represent a formidable test of the surgeon’s skill and good fortune. Dr. Charles Drake believed “it is likely that a complete, or incomplete, fenestration exists at the origin of all vertebral-basilar junction aneurysms” (Fig. 10.1). Certainly all nongiant saccular aneurysms in the senior author’s (DS) experience have been associated with such anomalies. In the most fortuitous situation the aneurysm will be found to arise from the proximal carina of the fenestration and to involve only one of the fenestration’s two limbs (Fig. 10.2). In more complex situations, the aneurysm may appear to engulf one entire limb and involve the other to variable degrees (Fig. 10.3); in addition, there may be two separate small aneurysms, each arising from different aspects of the same fenestration, or at least two lobes of a single aneurysm with a broad expansive neck. Recognition of the laterality of origin plays an important role in the selection of appropriate operative approach; we feel the best results are obtained by approaching these lesions from the side of their origin. Fig. 10.1 Fenestration of vertebrobasilar junction. Fig. 10.2 Fenestrated vertebrobasilar junction aneurysm. Fig. 10.3 Fenestrated vertebrobasilar junction aneurysm. Because these lesions originate at the proximal carina of the fenestration, a portion of their projection will normally be in a superior direction; the critical issue regarding projection relates to the aneurysm’s dome orientation in the sagittal plane. This may be posteriorly toward or even into the stem itself, or anteriorly toward the overlying clivus; again, awareness of the orientation of the dome with respect to the axis of the basilar artery is extremely important in design of the operative exposure. Aneurysms of the vertebrobasilar junction are situated near the junction of the proximal and middle thirds of the clivus and are routinely exposed through the cerebellopontine cistern via a far lateral suboccipital craniotomy, as described for aneurysms of the vertebral-posterior-inferior cerebellar artery origin. These patients are operated in the lateral decubitus position, with the neck fully flexed, the vertex tilted slightly toward the floor, and the head held in the true lateral position. The shoulder of the operative side is reflected forward to provide the surgeon an unimpeded vantage point from the lateral foramen magnum up along the petrous ridge through the CP angle. A shepherd’s crook or hockey stick incision extends superiorly from the mastoid tip to the superior nuchal line, then medially to the midline, and finally inferiorly to the midcervical area. The resultant scalp flap, along with the superficial muscular layer, is reflected laterally, held under tension with fishhook retractors. The groove between the digastric muscle and the attachment of the sternocleidomastoid muscle is identified, and the lateral mass of C1 is palpated. The attachments of the digastric, the semispinalis, splenius capitus, and both rectus muscles to the subocciput are cut, leaving a healthy cuff for reattachment. The broad muscle flap so formed is reflected inferiorly, and a midline incision in the fascia is made to expose and denude the ring of C1 and spinous process of C2. As the deeper attachments are cut, the flap will be reflected medially away from the mastoid process. Unlike the case of more proximal vertebral aneurysms, it is not necessary to expose and remove the arch of C1, and extracranial dissection of the vertebral artery is not done. The muscle flap is held, reflected inferiorly and medially, by fishhook retractors under tension. A generous suboccipital craniectomy is performed; the medial aspect of the sigmoid sinus is exposed along with the inferior aspect of the transverse sinus, and the occipital bone is removed almost to midline. The foramen magnum is opened medially and that resection is carried laterally to the level of the condyle, the posterior-medial aspect of which is carefully removed with the drill. The surgeon can expect significant venous bleeding from the bone over the sinuses, the dura itself, and the vertebral plexus between the lamina of C1 and the foramen magnum during the bony exposure, but it’s important not to desist until the inferolateral exposure has flattened the condyle sufficiently so that the sigmoid sinus can be seen extradurally passing behind the jugular tubercle. We open the dura mater in a K-shaped incision, the medial limb of which extends from the transverse sinus inferiorly across the cisterna magna to the lamina of C1. The superior limb of the K extends laterally to the sinodural angle and the inferior limb down to the bony margin of the condylar resection. The two dural flaps are then reflected tight against the lateral margin of the craniectomy defect with stay sutures.

Aneurysms of the Vertebrobasilar Junction

General

Anatomy

Projection

Procedure

Craniotomy

Microsurgical Exposure/Proximal and Distal Control

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree