Anxiety and obsessive–compulsive disorders

Terminology and classification

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)

Mixed anxiety and depressive disorder

Transcultural variations in anxiety disorder

Terminology and classification

The symptom of anxiety is found in many disorders. In the anxiety disorders, it is the most severe and prominent symptom, and it is also prominent in the obsessional disorders, although these are characterized by their striking obsessional symptoms. In DSM-IV, obsessive–compulsive disorder is classified as a type of anxiety disorder, but in ICD-10 it is classified separately. We have followed the DSM convention and included obsessional disorders in this chapter.

Anxiety disorders

Anxiety disorders are abnormal states in which the most striking features are mental and physical symptoms of anxiety, occurring in the absence of organic brain disease or another psychiatric disorder. The symptoms of anxiety are described on p. 5, and are listed for convenience in Table 9.1. Although all of the symptoms can occur in any of the anxiety disorders, there is a characteristic pattern in each disorder, which will be described later. The disorders share many features of their clinical picture and aetiology, but there are also differences:

• In generalized anxiety disorders, anxiety is continuous, although it may fluctuate in intensity.

• In phobic anxiety disorders, anxiety is intermittent, arising in particular circumstances.

• In panic disorder, anxiety is intermittent, but its occurrence is unrelated to any particular circumstances.

These differences (and some exceptions to these initial generalizations) will be explained further when the various types of anxiety disorders are described.

The development of ideas about anxiety disorders

Anxiety has long been recognized as a prominent symptom of many psychiatric disorders. Anxiety and depression often occur together and, until the last part of the nineteenth century, anxiety disorders were not classified separately from other mood disorders. It was Freud (1895b) who first suggested that cases with mainly anxiety symptoms should be recognized as a separate entity under the name ‘anxiety neurosis.’

Table 9.1 Symptoms of anxiety

Freud’s original anxiety neurosis included patients with phobias and panic attacks, but subsequently he divided it into two groups. The first group, which retained the name anxiety neurosis, included cases with mainly psychological symptoms of anxiety. The second group, which Freud called anxiety hysteria, included cases with mainly physical symptoms of anxiety and with phobias. Thus anxiety hysteria included the cases we now diagnose as agoraphobia. Freud originally proposed that the causes of anxiety neurosis and anxiety hysteria were related to sexual conflicts, although he later accepted a rather wider range of causes. By the 1930s, most psychiatrists considered that a very wide range of stressful problems could cause anxiety neurosis.

Phobic disorders have been recognized since antiquity, but the first systematic medical study of these conditions was probably that of Le Camus in the eighteenth century (Errera, 1962). The early nineteenth-century classifications assigned phobias to the group of monomanias, which were disorders of thinking rather than of emotion. However, when Westphal (1872) first described agoraphobia, he emphasized the importance of anxiety in the condition. Later, in 1895, Freud divided phobias into two groups—common phobias, in which there was an exaggerated fear of something that is commonly feared (e.g. darkness or high places), and specific phobias, in which there was fear of situations not feared by healthy people (e.g. open spaces) (Freud, 1895a, pp. 135–6). As will be explained later, the term specific phobia now has a rather different meaning.

In the 1960s, the different responses of certain phobias to behavioural methods suggested a grouping into simple phobias, social phobia, and agoraphobia, and these groups were also found to differ in their age of onset. (Simple phobias generally begin in childhood, social phobia in adolescence, and agoraphobia in early adult life.) At about the same time, it was observed that when phobias were accompanied by marked panic attacks, they responded poorly to behaviour therapy and better to imipramine (Klein, 1964). These cases were subsequently classified separately as panic disorder. This advance led to the present scheme of classification into generalized anxiety disorder, phobic anxiety disorder (simple, social, and agoraphobic), and panic disorder.

The relationship between obsessive–compulsive disorders and anxiety disorders has been and remains uncertain. Freud initially thought that phobias and obsessions were closely related (Freud, 1895a). He later proposed that anxiety is the central problem in both conditions and that their characteristic symptoms (phobias and obsessions) resulted from different kinds of defence mechanisms against anxiety. Others considered that obsessional disorders were a separate group of neuroses of uncertain aetiology. As explained above, this division of opinion is reflected today in the two major classification systems—in DSM-IV, obsessive–compulsive disorders are classified as a subgroup of the anxiety disorders, whereas in ICD-10, anxiety disorders and obsessive–compulsive disorders have separate places in the classification.

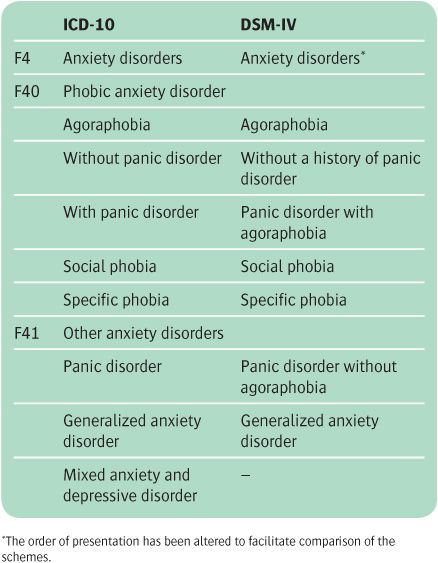

Table 9.2 Classification of anxiety disorders

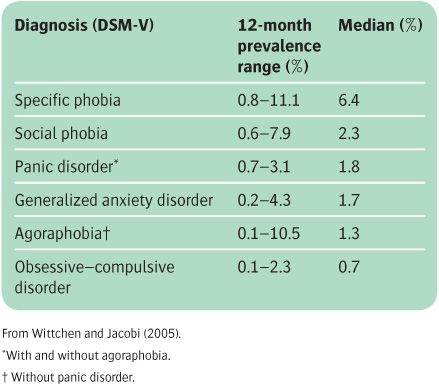

Table 9.3 Twelve-month prevalence rates of anxiety disorders in 21 population studies in the European Union

The classification of anxiety disorders

The classification of anxiety disorders in DSM-IV and ICD-10 is shown in Table 9.2. Although the two are broadly similar, there are four important differences:

• In ICD-10, anxiety disorders are divided into two named subgroups: (a) phobic anxiety disorder (F40) and (b) other anxiety disorder (F41), which includes panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder.

• Panic disorder is classified differently in the two schemes (the reasons for this are explained on p. 195).

• In DSM-IV, obsessive–compulsive disorder is classified as one of the anxiety disorders, but in ICD-10 it has a separate place in the classification.

• ICD-10 contains a category of mixed anxiety–depressive disorder, but DSM-IV does not.

The epidemiology of the various anxiety disorders is considered under each condition. The 12-month prevalence rates from a meta-analysis of 21 European studies are shown in Table 9.3 to illustrate the relative frequency of the different disorders in population studies.

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)

Clinical picture

The symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder (see Table 9.4) are persistent and are not restricted to, or markedly increased in, any particular set of circumstances (in contrast to phobic anxiety disorders). All of the symptoms of anxiety (see Table 9.1) can occur in generalized anxiety disorder, but there is a characteristic pattern which consists of the following features:

• worry and apprehension that are more prolonged than in healthy people. The worries are widespread and not focused on a specific issue as they are in panic disorder (i.e. on having a panic attack), social phobia (i.e. on being embarrassed), or obsessive–compulsive disorder (i.e. on contamination). The person feels that these widespread worries are difficult to control

• psychological arousal, which may be manifested as irritability, poor concentration, and/or sensitivity to noise. Some patients complain of poor memory, but this is due to poor concentration. If true memory impairment is found, a careful search should be made for a cause other than anxiety

• autonomic overactivity, which is most often experienced as sweating, palpitations, dry mouth, epigastric discomfort, and dizziness. However, patients may complain of any of the symptoms listed in Table 9.1. Some patients ask for help with any of these symptoms without mentioning spontaneously the psychological symptoms of anxiety

• muscle tension, which may be experienced as restlessness, trembling, inability to relax, headache (usually bilateral and frontal or occipital), and aching of the shoulders and back

• hyperventilation, which may lead to dizziness, tingling in the extremities and, paradoxically, a feeling of shortness of breath

• sleep disturbances, which include difficulty in falling asleep and persistent worrying thoughts. Sleep is often intermittent, unrefreshing, and accompanied by unpleasant dreams. Some patients have night terrors and wake suddenly feeling extremely anxious. Early-morning waking is not a feature of generalized anxiety disorder, and its presence strongly suggests a depressive disorder

• other features, which include tiredness, depressive symptoms, obsessional symptoms, and depersonalization. These symptoms are never the most prominent feature of a generalized anxiety disorder. If they are prominent, another diagnosis should be considered (see the section on differential diagnosis below).

Table 9.4 Symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder

Worry and apprehension |

Muscle tension* |

Autonomic overactivity* |

Psychological arousal* |

Sleep disturbance* |

Other features • Depression • Obsessions • Depersonalization |

Clinical signs

The face appears strained, the brow is furrowed, and the posture is tense. The person is restless and may tremble. The skin is pale, and sweating is common, especially from the hands, feet, and axillae. Being close to tears, which may at first suggest depression, reflects the generally apprehensive state.

Diagnostic conventions

There is no clear dividing line between generalized anxiety disorder and normal anxiety. They differ both in the extent of the symptoms and in their duration. The diagnostic criteria for both extent and duration are arbitrary, and they differ in several ways between DSM-IV and ICD-10. With regard to extent, both DSM-IV and the research version of ICD-10 require the presence of a minimum number of symptoms from a list. However, the ICD-10 list contains 22 physical symptoms of anxiety, whereas there are only 6 such symptoms in the DSM-IV list. Furthermore, in DSM-IV but not in ICD-10, worry is a key symptom. DSM-IV requires that the symptoms cause clinically significant distress or problems in functioning in daily life.

With regard to duration, in DSM-IV and the research version of ICD-10, symptoms must have been present for 6 months. However, the ICD-10 criteria for clinical practice are more flexible—symptoms should have been present on ‘most days for at least several weeks at a time, and usually several months.’

Comorbidity

Anxiety and depression

The two classifications differ in their approach to cases that present with significant symptoms of both depressive disorder and generalized anxiety without meeting the full criteria for either condition considered separately. ICD-10 has a separate category for these cases, namely mixed anxiety and depressive disorder. This category is not included in DSM-IV (although it is included among ‘criteria sets for further study’). These conditions are discussed further below (see p. 198) and in Chapter 10.

Generalized anxiety disorder and other anxiety disorders

DSM-IV and ICD-10 differ in the guidance that they give about the circumstances in which two diagnoses should be made.

• In ICD-10, generalized anxiety disorder is not diagnosed if the symptoms fulfil the diagnostic criteria for phobic anxiety disorder (F40), panic disorder (F41), or obsessive–compulsive disorder (F42).

• In DSM-IV, the emphasis that is placed on the worrying ideas in general anxiety disorder makes it possible to diagnose generalized anxiety disorder when those ideas are present even in the presence of symptoms of one of the other three anxiety diagnoses. When this convention is followed, comorbidity between generalized anxiety disorder and other anxiety disorders is frequent (social phobia in 23% of cases of generalized anxiety disorder, simple phobia in 21%, and panic disorder in 11%) (see Tyrer and Baldwin, 2006).

Differential diagnosis

Generalized anxiety disorder has to be distinguished not only from other psychiatric disorders but also from certain physical conditions. Anxiety symptoms can occur in nearly all of the psychiatric disorders, but there are some in which particular diagnostic difficulties arise.

Depressive disorder

Anxiety is a common symptom in depressive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder often includes some depressive symptoms. The usual convention is that the diagnosis is decided on the basis of the severity of two kinds of symptom and the order in which they appeared. Information on these two points should be obtained, if possible, from a relative or other informant as well as from the patient. Whichever type of symptoms appeared first and is more severe is considered primary. An important diagnostic error is to misdiagnose the agitated type of severe depressive disorder as generalized anxiety disorder. This mistake will seldom be made if anxious patients are asked routinely about symptoms of a depressive disorder, including depressive thinking and, when appropriate, suicidal ideas. Depressive disorders are often worst in the morning, and anxiety that is worst at this time suggests a depressive disorder.

Schizophrenia

People with schizophrenia sometimes complain of anxiety before the other symptoms are recognized. The chance of misdiagnosis can be reduced by asking anxious patients routinely what they think caused their symptoms. Schizophrenic patients may give an unusual reply, which leads to the discovery of previously unexpressed delusional ideas.

Dementia

Anxiety may be the first abnormality to be complained of by a person with presenile or senile dementia. When this happens, the clinician may not detect an associated impairment of memory, or may dismiss it as the result of poor concentration. Therefore memory should be assessed in middle-aged or older patients who present with anxiety.

Substance misuse

Some people take drugs or alcohol to relieve anxiety. Patients who are dependent on drugs or alcohol sometimes believe that the symptoms of drug withdrawal are those of anxiety, and take anxiolytic or other drugs to control them. The clinician should be alert to this possibility, particularly when anxiety is severe on waking in the morning, which is the time when alcohol and drug withdrawal symptoms tend to occur. (Anxiety that is worst in the morning also suggests depressive disorder; see above.)

Physical illness

Some physical illnesses have symptoms that can be mistaken for those of an anxiety disorder. This possibility should be considered in all cases, but especially when there is no obvious psychological cause of anxiety, or there is no history of past anxiety. The following conditions are particularly important:

• In thyrotoxicosis, the patient may be irritable and restless, with tremor and tachycardia. Physical examination may reveal characteristic signs of thyrotoxicosis, such as an enlarged thyroid, atrial fibrillation, and exophthalmos. If there is any doubt, thyroid function tests should be arranged.

• Phaeochromocytoma and hypoglycaemia usually cause episodic symptoms, and are therefore more likely to mimic a phobic disorder or panic disorder. However, they should also be considered as a differential diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder. If there is any doubt, appropriate physical examination and laboratory tests should be carried out.

Anxiety secondary to the symptoms of physical illness

Sometimes the first complaint of a physically ill person is anxiety caused by worry that certain physical symptoms portend a serious illness. If the physical symptoms are non-specific, they may be mistakenly attributed to anxiety. Furthermore, some patients do not mention all of the physical symptoms unless questioned. This is particularly likely when the patient has a special reason to fear serious illness—for example, if a relative or friend died of cancer after developing similar symptoms. It is good practice to ask anxious patients with physical symptoms whether they know anyone who has had similar symptoms.

Generalized anxiety disorder that is mistaken for physical illness

When this happens, extensive investigations may be carried out which increase the patient’s anxiety. Although physical illness should be considered in every case, it is also important to remember the diversity of the anxiety symptoms. Palpitations, headache, frequency of micturition, and abdominal discomfort can all be the primary complaint of an anxious patient. Correct diagnosis requires systematic enquiries about other symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder, and about the order in which the various symptoms appeared.

Epidemiology

Estimates of incidence and prevalence vary according to the diagnostic criteria used in the survey, and whether a clinical significance criterion is used. The Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey found a 12-month prevalence of 4.4% for generalized anxiety disorder in England (McManus et al., 2007), and a similar figure has been reported in US surveys, with rather lower prevalence figures in European countries (1–2%) (Gale and Davidson, 2007). Worldwide estimates of the proportion of the population who are likely to suffer from generalized anxiety disorder in their lifetime vary between 0.8% and 6.4% (Kessler and Wang, 2008). Generalized anxiety disorder is associated with several indices of social disadvantage, including lower household income and unemployment, as well as divorce and separation (McManus et al., 2007).

Aetiology

In general terms, generalized anxiety disorder appears to be caused by stressors acting on a personality that is predisposed to anxiety by a combination of genetic factors and environmental influences in childhood. However, evidence for the nature and importance of these causes is incomplete.

Stressful events

Clinical observations indicate that generalized anxiety disorders often begin in relation to stressful events, and some become chronic when stressful problems persist. A study by Kendler et al. (2003) showed that stressful life events characterized by loss increased the risk of both depression and generalized anxiety disorder. However, life events characterized by ‘danger’ (where the full import of the event was yet to be realized) were more common in those who subsequently developed generalized anxiety disorder.

Genetic causes

Early twin studies, such as that by Slater and Shields (1969), showed a higher concordance for anxiety disorder between monozygotic than dizygotic pairs, which suggests that the familial association has a genetic cause. A family study found that the risk of generalized anxiety disorder in first-degree relatives of patients with the disorder was five times that in controls (Noyes et al., 1987). However, the genes involved in the transmission of generalized anxiety disorder appear to increase susceptibility to other anxiety conditions, such as panic disorder and agoraphobia, as well as to major depression. Overall, the findings suggest that genes play a significant although moderate role in the aetiology of generalized anxiety disorder, but that the genes involved predispose to a range of anxiety and depressive disorders, rather than generalized anxiety disorder specifically (Hettema et al., 2005; Hettema, 2008).

Early experiences

Accounts given by anxious patients of their experience in childhood suggest that early adverse experience is a cause of generalized anxiety disorder. These accounts have given rise to objective studies and to psychoanalytic theories.

Objective studies. Brown and Harris (1993) studied the relationship between adverse experience in childhood and anxiety disorder in adult life in 404 working-class women living in an inner city. Adverse early experience was assessed from patients’ accounts of parental indifference and of physical or sexual abuse. Women who reported early adversity had increased rates of generalized anxiety disorder (and also of agoraphobia and depressive disorder, but not of simple phobia). Parenting styles characterized by overprotection and lack of emotional warmth may also be a risk factor for generalized anxiety disorder as well as for other anxiety and depressive disorders in offspring (see Chorpita and Barlow, 1998). Kendler et al. (1992) found that the rate of anxiety disorder (and several other psychiatric disorders) was higher in women who had been separated from their mother before the age of 17 years.

Psychoanalytic theories. Psychoanalytical theory proposes that anxiety arises from intrapsychic conflict when the ego is overwhelmed by excitation from any of the following three sources:

• the outside world (realistic anxiety)

• the instinctual levels of the id, including love, anger, and sex (neurotic anxiety)

• the superego (moral anxiety).

According to this theory, in generalized anxiety disorder, anxiety is experienced directly unmodified by the defence mechanisms that are thought to be the basis of phobias or obsessions (see p. 187 and p. 202). The theory proposes that in generalized anxiety disorders the ego is readily overwhelmed because it has been weakened by a development failure in childhood. Normally, children overcome this anxiety through secure relationships with loving parents. However, if they do not achieve this security, as adults they will be vulnerable to anxiety when experiencing separation or potentially threatening events. Thus both psychoanalytic ideas and objective studies suggest that good parenting can protect against anxiety by giving the child a secure emotional base from which to explore an uncertain world.

Cognitive–behavioural theories

Conditioning theories propose that generalized anxiety disorders arise when there is an inherited predisposition to excessive responsiveness of the autonomic nervous system, together with generalization of the responses through conditioning of anxiety to previously neutral stimuli. This theory has not been supported by a body of objective data.

Cognitive theory. Particular coping and cognitive styles may also predispose individuals to the development of generalized anxiety disorder, although it is not always easy to distinguish predisposition from the abnormal cognitions that are seen in the illness itself. As noted above, it seems likely that people who lack a sense of control of events and of personal effectiveness, perhaps due to early life experiences, are more prone to anxiety disorders. Such individuals may also demonstrate trait-like cognitive biases in the form of increased attention to potentially threatening stimuli, overestimation of environmental threat, and enhanced memory of threatening material. This has been referred to as the looming cognitive style, which appears to be a general psychological vulnerability factor for a number of anxiety disorders (Reardon and Nathan, 2007). More recent cognitive formulations have focused on the process of worry itself. It has been proposed that people who are predisposed to generalized anxiety disorder use worry as a positive coping strategy for dealing with potential threats, whereby the individual cannot relax until they have examined all of the possible dangers and identified ways of dealing with them. However, this can lead to ‘worry about worry’, when a person come to believe, for example, that worrying in this way, although necessary for them, is also uncontrollable and harmful. This ‘metacognitive belief’ may form a transition between excessive but normal worrying, and generalized anxiety disorder (Wells, 2005).

Personality

Personality traits. The symptom of anxiety is associated with neuroticism, and twin studies have shown an overlap between the genetic factors related to neuroticism and those related to generalized anxiety disorder (Hettema et al., 2004).

Personality disorder. Generalized anxiety disorder occurs in people with anxious–avoidant personality disorders, but also in individuals with other personality disorders.

Neurobiological mechanisms

The neurobiological mechanisms involved in generalized anxiety disorder are presumably those that mediate normal anxiety. The mechanisms are complex, involving several brain systems and several neurotransmitters. Studies in animals have indicated a key role for the amygdala, which receives sensory information both directly from the thalamus and from a longer pathway involving the somatosensory cortex and anterior cingulate cortex. Cortical involvement in anxiety is important because it indicates a role for cognitive processes in its expression (see LeDoux, 2000). The hippocampus is also believed to have an important role in the regulation of anxiety, because it relates fearful memories to relevant present contexts. Breakdown of this mechanism could lead to an overgeneralization of fear in response to non-threatening stimuli.

Animal experimental studies have led to an understanding of the regulation of anxiety in the brain by neurotransmitters and neuromodulators. Noradrenergic neurons that originate in the locus coeruleus increase arousal and anxiety, whereas 5-HT neurons that arise in the raphe nuclei appear to have complex effects, some of which reduce anxiety, while others are anxiogenic. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors, which are widely distributed in the brain, are inhibitory and reduce anxiety, as do the associated benzodiazepine-binding sites. There is probably also an important role for corticotropin-releasing hormone, which increases anxiety-related behaviours and is found in high concentration in the amygdala. However, although pharmacological manipulation of 5-HT and GABA mechanisms can be helpful in the treatment of generalized anxiety, there is no firm evidence that changes in these neurotransmitters are involved in the pathophysiology of the disorder (Garner et al., 2009).

Functional imaging of the brain during the presentation of aversive stimuli (e.g. fearful faces) has demonstrated increased activity of the amygdala and insula in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. There is also altered activity in cortical regions thought to be involved in emotional presentation, such as the ventrolateral pre-frontal cortex. It is unclear how specific these changes might be for generalized anxiety disorder, as opposed to other forms of anxiety disorder (Engel et al., 2009).

Prognosis

One of the DSM-IV criteria for generalized anxiety disorder is that the symptoms should have been present for 6 months. One of the reasons for this cut-off is that anxiety disorders which last for longer than 6 months have a poor prognosis. Thus most clinical studies suggest that generalized anxiety disorder is typically a chronic condition with low rates of remission over the short and medium term. Evaluation of the prognosis is complicated by the frequent comorbidity with other anxiety disorders and depression, which worsen the long-term outcome and accompanying burden of disability (Tyrer and Baldwin, 2006). In the Harvard–Brown Anxiety Research Program, which recruited patients from Boston hospitals, the mean age of onset of generalized anxiety disorder was 21 years, although many patients had been unwell since their teenage years. The average duration of illness in this group was about 20 years, and despite treatment the outcome over the next 3 years was relatively poor, with only one in four patients showing symptomatic remission from generalized anxiety disorder (Yonkers et al., 1996).

However, the participants in the above study were recruited from hospital services, and may not be representative of generalized anxiety disorder in community settings. In a naturalistic study in the UK, Tyrer and colleagues (2004a) followed up patients with anxiety and depression identified in primary care and found that 12 years later, 40% of those initially diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder had recovered, in the sense that they no longer met the criteria for any DSM-III psychiatric disorder. The remaining participants continued to be symptomatic, but in only 3% was generalized anxiety disorder still the principal diagnosis. In the vast majority of patients, conditions such as dysthymia, major depression, and agoraphobia were now more prominent. This study confirms the chronic and fluctuating symptomatic course of generalized anxiety disorder in many clinically identified patients.

Treatment

Self-help and psychoeducation

A variety of forms of self-help have been studied in patients with anxiety disorders, including generalized anxiety disorder. Such approaches typically include written and electronic materials with information about the disorder, and practical exercises to carry out based on the principles of cognitive–behaviour therapy. Typically self-help has minimal therapist input, but it is also possible for self-help for anxiety disorders to be guided by a trained practitioner (guided self-help). Another form of educational treatment takes place in group form, so-called group psychoeducation, where one therapist works with up to a dozen clients in about six weekly sessions of interactive learning and shared experience. The evidence for the benefit of these forms of treatment is limited and the effects, although superior to no treatment, appear to be modest. However, these approaches are useful as part of an initial stepped-care approach (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2010a).

Relaxation training

If practised regularly, relaxation appears to be able to reduce anxiety in less severe cases. However, many patients with such disorders do not practise the relaxation exercises regularly. Motivation may be improved if the training takes place in a group, and some people engage more with treatment when relaxation is taught as part of a programme of yoga exercises. A structured therapy, known as applied relaxation, does appear to be effective in lowering anxiety over 12–15 sessions guided by a trained therapist (Hoyer et al., 2009). A critical element of this treatment is the application of learned relaxation skills to anxiety-provoking situations.

Cognitive–behaviour therapy

This treatment combines relaxation with cognitive procedures designed to help patients to control worrying thoughts. The method is described on p. 584. Compared with treatment as usual, cognitive–behaviour therapy produces quite substantial benefits in terms of symptom resolution, with relatively few dropouts (Hofmann and Smits, 2008). However, the outcome obtained with cognitive therapy does not appear to differ from that obtained with other kinds of psychological interventions, such as applied relaxation and non-directive counselling, and there are few data on longer-term outcomes (Hunot et al., 2007).

Medication

Anxiolytic drugs are described on p. 515. Here we are concerned with some specific points about their use in generalized anxiety disorders. Medication can be used to bring symptoms under control quickly while the effects of psychological treatment are awaited. It can also be used when psychological treatment has failed. However, medication is often prescribed too readily and for too long. Before prescribing, it is appropriate to recall that even though generalized anxiety disorder is said to have a poor prognosis, in short-term studies of medication, pill placebo treatment in the context of the clinical care provided by a controlled trial is beneficial for a significant proportion of patients. For example, in a 12-week, placebo-controlled trial of escitalopram and paroxetine, just over 40% of patients responded to placebo, and around 30% reached remission (Baldwin et al., 2006).

Short-term treatment. One of the longer-acting benzodiazepines, such as diazepam, is appropriate for the short-term treatment of generalized anxiety disorders—for example, diazepam in a dose ranging from 5 mg twice daily in mild cases to 10 mg three times daily in the most severe cases. Anxiolytic drugs should seldom be prescribed for more than 3 weeks, because of the risk of dependence when they are given for longer. Buspirone (see p. 518) is similarly effective for short-term management of generalized anxiety disorder and is less likely to cause dependency, but has a slower onset of action. Beta-adrenergic antagonists (see p. 518) are sometimes used to control anxiety associated with sympathetic stimulation. However, they are more often used for performance anxiety (see p. 191) than for generalized anxiety disorder. If one of these drugs is used, care should be taken to observe the contraindications to treatment and the advice given on p. 519 and in the manufacturer’s literature.

Long-term treatment. Because generalized anxiety disorder often requires lengthy treatment, for which benzodiazepines are unsuitable (see above), and is often comorbid with depression and other anxiety disorders, treatment guidelines usually recommend selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) as the initial choice (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2010a). Serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) such as duloxetine and venlafaxine are also effective, but are thought to be somewhat less well tolerated than SSRIs. The anti-convulsant pregabalin is also licensed for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in the UK (see p. 519). It has a different side-effect profile to SSRIs and SNRIs, and might therefore be useful in patients who cannot tolerate the latter agents. Where patients with generalized anxiety disorder respond to medication, the risk of relapse is substantially reduced if treatment is maintained for at least 6 months, and probably longer (Donovan et al., 2010; Rickels et al., 2010).

For a review of the pharmacological treatment of generalized anxiety disorder, see Davidson et al. (2010).

Management

In primary care, many patients are seen in the early stage of an anxiety disorder before a formal diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder can be made. In these circumstances, simple steps such as education and self-help can be tried first. If anxiety is severe, a short course of a benzodiazepine can bring rapid relief. Psychiatrists are more likely to encounter established cases. The steps in the management of such patients can be summarized as follows:

• Check the diagnosis and comorbidity, especially depressive disorder, substance abuse, or a physical cause such as thyrotoxicosis. If any of these are present, treat them appropriately.

• Evaluate psychosocial maintaining factors such as persistent social problems, relationship conflict, and concerns that physical symptoms of anxiety are evidence of serious physical disease.

• Explain the evaluation and proposed treatment, especially the origins of any physical symptoms of anxiety. Discuss the way in which the patient might describe the condition to employers, friends, and family. Self-help books reinforce the explanation and describe simple cognitive–behavioural techniques that people can use on their own or as part of a wider plan of treatment.

• Offer structured psychological treatments, such as cognitive–behaviour therapy or applied relaxation. For patients who do not respond to these initial approaches or who have significant functional disability, benefit can be obtained by using a structured treatment such as cognitive–behaviour therapy administered by a trained therapist.

• Consider the use of medication. A short course of benzodiazepines may be prescribed to reduce high levels of anxiety initially, but should seldom be given for more than about 3 weeks. Where psychological treatment is not available or has failed, medication—usually with an SSRI initially—is appropriate. The main uses and side-effects of medication should be discussed as when using the same drugs in the treatment of depression (see p. 538).

• Discuss the plan with the patient, the general practitioner, and the community team and allocate tasks and responsibility appropriately. Plans should recognize that generalized anxiety disorder is often a long-term problem.

A recent guideline from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2010a) describes a stepped-care approach to the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder (see Box 9.1).

Phobic anxiety disorders

Phobic anxiety disorders have the same core symptoms as generalized anxiety disorders, but these symptoms occur only in specific circumstances. In some phobic disorders these circumstances are few and the patient is free from anxiety for most of the time. In other phobic disorders many circumstances provoke anxiety, and consequently anxiety is more frequent, but even so there are some situations in which no anxiety is experienced. Two other features characterize phobic disorders. First, the person avoids circumstances that provoke anxiety, and secondly, they experience anticipatory anxiety when there is the prospect of encountering these circumstances. The circumstances that provoke anxiety can be grouped into situations (e.g. crowded places), ‘objects’ (a term that includes living things such as spiders), and natural phenomena (e.g. thunder). For clinical purposes, three principal phobic syndromes are recognized—specific phobia, social phobia, and agoraphobia. These syndromes will be described next.

Classification of phobic disorders

In DSM-IV and ICD-10, phobic disorders are divided into specific phobia, social phobia, and agoraphobia. In DSM-IV, but not in ICD-10, agoraphobic patients who have regular panic attacks (more than four attacks in 4 weeks, or one attack followed by 1 month of persistent fear of having another) are classified as having panic disorder. The reasons for this convention are explained on p. 195.

Specific phobia

Clinical picture

A person with a specific phobia is inappropriately anxious in the presence of a particular object or situation. In the presence of that object or situation, the person experiences the symptoms of anxiety listed in Table 9.1. Anticipatory anxiety is common, and the person usually seeks to escape from and avoid the feared situation. Specific phobias can be characterized further by adding the name of the stimulus (e.g. spider phobia). In the past it was common to use terms such as arachnophobia (instead of spider phobia) or acrophobia (instead of phobia of heights), but this practice adds nothing of value to the use of the simpler names.

In DSM-IV, four types of specific phobia are recognized, which are concerned with:

• animals

• aspects of the natural environment

• blood, injection, and injury

• situations and other provoking agents. This group includes fears of dental and medical situations and fears of choking.

The following specific phobias merit brief separate consideration.

Phobia of dental treatment

Around 5% of adults have a fear of dental treatment. These fears can become so severe that all dental treatment is avoided and serious caries develops. A meta-analysis of 38 studies of behavioural treatment found a significant reduction in fear, with on average 77% of treated individuals attending for dental treatment 4 years after the treatment (Kvale et al., 2004).

Phobia of flying

Anxiety during aeroplane travel is common. A few people experience such intense anxiety that they are unable to travel in an aeroplane, and some seek treatment. This fear also occurs occasionally among pilots who have had an accident while flying. Desensitization treatment (see p. 581) is provided by some airlines, and self-help books are available. Virtual reality programmes have been used to replace actual and imagined exposure. Good results have been reported, but it is unclear whether the treatment needs to be supplemented with other psychological measures, such as psychoeducation (Da Costa et al., 2008).

Phobia of blood and injury

In this phobia, the sight of blood or of an injury results in anxiety. However, the accompanying autonomic response differs from that in other phobic disorders. The initial tachycardia is followed by a vasovagal response, with bradycardia, pallor, dizziness, nausea, and sometimes fainting. It has been reported that individuals who have this kind of phobia are prone to develop neurally mediated syncope even without the specific blood injury stimulus. Treatment consists of exposure in vivo together with the use of muscular tension to help to prevent syncope (Ayala et al., 2009).

Phobia of choking

People with this kind of phobia are intensely concerned that they will choke when attempting to swallow. They have an exaggerated gag reflex and feel intensely anxious when they attempt to swallow. The onset is either in childhood, or after choking on food in adulthood. Some of these individuals also fear dental treatment, while others avoid eating in public. Treatment consists of desensitization.

Phobia of illness

People with this phobia experience repeated fearful thoughts that they might have cancer, venereal disease, or some other serious illness. Unlike people with delusions, people with phobias of illness recognize that these thoughts are irrational, at least when the thoughts are not present. Moreover, they do not resist the thoughts in the way that obsessional thoughts are resisted. Such individuals may avoid hospitals, but the thoughts are not otherwise specific to situations. If the person is convinced that they have the disease, the condition is classified as hypochondriasis (see p. 398). If the thoughts are recognized as irrational and are resisted, the condition is classified as obsessive–compulsive disorder.

Epidemiology

Among adults, the lifetime prevalence of specific phobias has been estimated, using DSM-IV criteria, to be around 7% in men and 17% in women (Kessler et al., 2005a). The age of onset of most specific phobias is in childhood. The onset of phobias of animals occurs at an average age of 7 years, blood phobia at around 8 years, and most situational phobias develop in the early twenties (Öst et al., 2001).

Aetiology

Persistence of childhood fears

Most specific phobias in adulthood are a continuation of childhood phobias. Specific phobias are common in childhood (see p. 662). By the early teenage years most of these childhood fears will have been lost, but a few persist into adult life. Why they persist is not certain, except that the most severe phobias are likely to last the longest.

Genetic factors

In one study, 31% of first-degree relatives of people with specific phobia also had the condition (Fyer et al., 1995). The results of a study of female twins with specific phobia fitted an aetiological model in which a modest genetic vulnerability was combined with phobia-specific stressful events (Kendler et al., 1999). The genetic vulnerability may involve differences in the strength of fear conditioning, which has a heritability of around 40% (Hettema et al., 2003).

Psychoanalytical theories

These theories suggest that phobias are not related to the obvious external stimulus, but to an internal source of anxiety. The internal source is excluded from consciousness by repression and attached to the external object by displacement. This theory is not supported by objective evidence.

Conditioning and cognitive theories

Conditioning theory suggests that specific phobias arise through association learning. A minority of specific phobias appear to begin in this way in adulthood, in relation to a highly stressful experience. For example, a phobia of horses may begin after a dangerous encounter with a bolting horse. Some specific phobias may be acquired by observational learning, as the child observes another person’s fear responses and learns to fear the same stimuli. Cognitive factors are also involved in the maintenance of the fear, especially fearful anticipation of and selective attention to the phobic stimuli.

Prepared learning

This term refers to an innate predisposition to develop persistent fear responses to certain stimuli. Some young primates seem to be prepared to develop fears of snakes, but it is not certain whether the same process accounts for some of the specific phobias of human children.

Cerebral localization

Functional imaging studies have revealed hyperactivity of the amygdala upon presentation of the feared stimulus, which appears to diminish with successful treatment. Anticipation of a phobic stimulus activates the anterior cingulate cortex and the insular cortex. There is inconsistent evidence for diminished activity of the medial pre-frontal cortex (Engel et al., 2009).

Differential diagnosis

Diagnosis is seldom difficult. The possibility of an underlying depressive disorder should always be kept in mind, since some patients seek help for long-standing specific phobias when a depressive disorder makes them less able to tolerate their phobic symptoms. Obsessional disorders sometimes present with fear and avoidance of certain objects (e.g. knives) (see p. 200). In such cases a systematic history and mental state examination will reveal the associated obsessional thoughts (e.g. thoughts of harming a person with a knife).

Prognosis

The prognosis of specific phobia in adulthood has not been studied systematically. Clinical experience suggests that specific phobias which originate in childhood continue for many years, whereas those that start after stressful events in adulthood have a better prognosis.

Treatment

The main treatment is the exposure form of behaviour therapy (see p. 581). With this treatment, the phobia is usually reduced considerably in intensity and so is the social disability. However, it is unusual for the phobia to be lost altogether. The outcome depends importantly on repeated and prolonged exposure, and dropout rates of up to 50% have been reported (Schneier et al., 1995). Some patients seek help soon before an important engagement that will be made difficult by the phobia. When this happens, a few doses of a benzodiazepine may be prescribed to relieve phobic anxiety until a treatment can be arranged. Exposure usually takes place over several 1-hour sessions, but it can be carried out in a single very long and intensive session lasting for several hours. Virtual-reality exposure may also be of benefit (Da Costa et al., 2008). Although pharmacotherapy has not been regarded as useful in the treatment of specific phobias, there is preliminary evidence that d-cycloserine, a partial agonist at the glutamate NMDA receptor, may be helpful in augmenting the effectiveness of exposure treatment of phobias (Ganasen et al., 2010). In animals, d-cycloserine facilitates fear extinction, and it is possible that a similar mechanism may be involved when d-cycloserine is combined with behaviour therapy in humans.

Social phobia

Clinical picture

In this disorder, inappropriate anxiety is experienced in social situations in which the person feels observed by others and could be criticized by them. Socially phobic people attempt to avoid such situations. If they cannot avoid them, they try not to engage in them fully—for example, they avoid making conversation, or they sit in the place where they are least conspicuous. Even the prospect of encountering the situation may cause considerable anxiety, which is often misconstrued as shyness. Social phobia can be distinguished from shyness by the levels of personal distress and associated social and occupational impairment (Stein and Stein, 2008).

The situations in which social phobia occurs include restaurants, canteens, dinner parties, seminars, board meetings, and other places where the person feels observed by other people. Some patients become anxious in a wide range of social situations (generalized social phobia), whereas others are anxious only in specific situations, such as public speaking, writing in front of others, or playing a musical instrument in public. These discrete social phobias are classified separately in DSM-IV (although not in ICD-10).

People with social phobia may experience any of the anxiety symptoms listed in Table 9.4, but complaints of blushing and trembling are particularly frequent. Socially phobic people are often preoccupied with the idea of being observed critically, although they are aware that this idea is groundless.

The cognitions centre around a fear of being evaluated critically by others. These cognitions are described in more detail in the section on aetiology below.

Other problems. Some patients take alcohol to relieve the symptoms of anxiety, and alcohol misuse is more common in social phobia than in other phobias. Social phobia is also a predictor of alcohol misuse. Comorbid depressive disorders as well as other anxiety disorders are also common (Kessler, 2005).

Onset and development. The condition usually begins in the early teenage years. The first episode occurs in a public place, usually without an apparent reason. Subsequently, anxiety is felt in similar places, and the episodes become progressively more severe with increasing avoidance.

Two discrete social phobias require separate consideration, namely phobias of excretion and of vomiting.

Phobia of excretion

Patients with these phobias either become anxious and unable to pass urine in public lavatories, or have frequent urges to pass urine, with an associated fear of incontinence. These individuals organize their lives so that they are never far from a lavatory. A smaller group have comparable symptoms centred around defecation.

Phobias of vomiting

Some patients fear that they may vomit in a public place, often a bus or train, and in these surroundings they experience nausea and anxiety. A smaller group have repeated fears that other people will vomit in their presence.

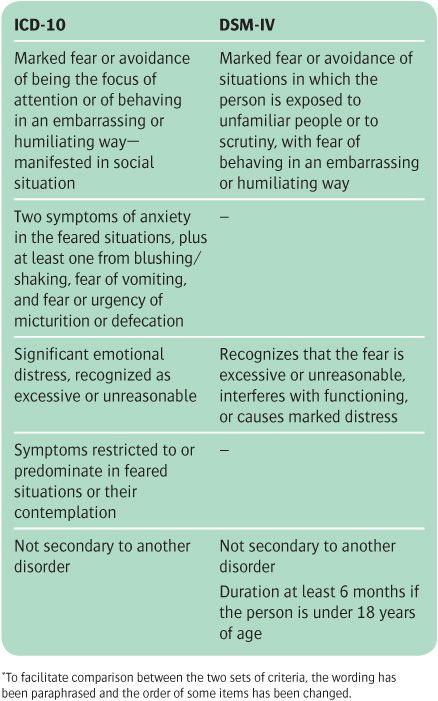

Diagnostic conventions

Table 9.5 shows, in summary form, the criteria for the diagnosis of social phobia in ICD-10 and DSM-IV. The requirements are similar (although the original wordings differ more than the paraphrased versions in the table). In ICD-10 there is greater emphasis on symptoms of anxiety—two general symptoms of anxiety, and one of three symptoms associated with social phobia. DSM-IV has an additional criterion that symptoms must have been present for at least 6 months if the person is under 18 years of age.

Table 9.5 Abbreviated diagnostic criteria for social phobia in ICD-10 and DSM-IV*

Differential diagnosis

Agoraphobia and panic disorder. The symptom of social phobia can occur in either of these disorders, in which case both diagnoses can be made, although it is generally more useful for the clinician to decide which syndrome should be given priority.

Generalized anxiety disorder and depressive disorder. Social phobia has to be distinguished from the former by establishing the situations in which anxiety occurs, and from the latter from the history and mental state examination.

Schizophrenia. Some patients with schizophrenia avoid social situations because they have persecutory delusions. Although, when they are in the feared situation, people with social phobia may feel convinced by their ideas that they are being observed, when they are away from the situation they know that these ideas are false.

Body dysmorphic disorder. People with this disorder may avoid social situations, but the diagnosis is usually clear from the patient’s account of the problem.

Avoidant personality disorder. Social phobia has to be distinguished from a personality characterized by lifelong shyness and lack of self-confidence. In principle, social phobia has a recognizable onset and a shorter history, but in practice the distinction may be difficult to make, as social phobia usually begins in adolescence and the exact onset may be difficult to recall. Many people have disorders that meet the criteria for both diagnoses (Blackmore et al., 2009).

Inadequate social skills. This is a primary lack of social skills, with secondary anxiety. It is not a phobic disorder, but a type of behaviour that occurs in personality disorders, in schizophrenia, and among people of low intelligence. Its features include hesitant, dull, and inaudible diction, inappropriate use of facial expression and gesture, and failure to look at other people during conversation.

Normal shyness. Some people who have none of the above disorders are shy and feel ill at ease in company. As noted above, the diagnostic criteria for social phobia set a level of severity that is intended to exclude these individuals (Stein and Stein, 2008).

Epidemiology

The National Comorbidity Survey Replication reported a lifetime prevalence rate of social phobia in the community of around 12%. The rate is therefore not much lower than that of specific phobia. Social phobias are about equally frequent among the men and women who seek treatment, but in community surveys they are reported rather more frequently by women (Kessler et al., 2005a,b). As noted above, social phobia is associated with depression and alcoholism.

Aetiology

Genetic factors

Genetic factors are suggested by the finding that social phobias (but not other anxiety disorders) are more common among the relatives of people with social phobia than in the general population (Tillfors, 2004). The concordance rate of social phobia in monozygotic twins (around 24%) is higher than that seen in dizygotic twins (around 15%). The heritability of social phobia appears to be greater in women (around 50%) than in men (around 25%).

Conditioning

Most social phobias begin with a sudden episode of anxiety in circumstances similar to those which become the stimulus for the phobia, and it is possible that the subsequent development of phobic symptoms occurs partly through conditioning.

Cognitive factors

The principal cognitive factor in the aetiology of social phobia is an undue concern that other people will be critical of the person in social situations (often referred to as a fear of negative evaluation). This concern is accompanied by several other ways of thinking, including:

• excessively high standards for social performance

• negative beliefs about the self (e.g. ‘I’m boring’)

• excessive monitoring of one’s own performance in social situations

• intrusive negative images of the self as supposedly seen by others.

People with social phobia often adopt safety behaviours (see p. 585), such as avoiding eye contact, which make it harder for them to interact normally. For a review of the cognitive model of social phobia, see Moscovitch (2009).

Neural mechanisms

Functional neuroimaging studies have found that patients with social phobia have increased amygdala responses to presentation of faces with expressions of negative affect. The anticipation of public speaking in individuals with social phobia produced activation in limbic and paralimbic regions, including the amygdala, hippocampus and insula, while activation of cortical regulatory areas such as the anterior cingulate cortex and prefrontal cortex was diminished. During public speaking, patients continued to exhibit increased activity in limbic and paralimbic regions, while healthy controls showed more activation in cortical regulatory areas (Engel et al., 2009).

Course and prognosis

Social phobia has an early onset, usually in childhood or adolescence, and can persist over many years, sometimes even into old age. Only about 50% of people with the disorder seek treatment, usually after many years of symptoms (Wang et al., 2005).

Treatment

Psychological treatment

Cognitive–behaviour therapy is the psychological treatment of choice for social phobia (for a description of this treatment, see p. 584). The original cognitive procedures were based on those used successfully to treat agoraphobia and panic disorder, and when added to exposure did not greatly increase the benefit. A modified form of cognitive–behaviour therapy appears to be more effective. This modified treatment is based on the particular cognitive abnormalities that are found in social phobia (see the section on aetiology above), coupled with measures to reduce safety behaviours (see p. 585), and using video or audio feedback (see Clark et al., 2006). Cognitive–behaviour therapy can be given in a group format, but this may not be as effective as individual treatment (Mortberg et al., 2007).

Dynamic psychotherapy. Clinical experience suggests that this treatment may help some patients, particularly those whose social phobia is associated with pre-existing problems in personal relationships. However, there have been no controlled trials to test this possibility.

Drug treatment

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Treatment guidelines generally recommend SSRIs as the first choice of pharmacological treatment in the management of social phobia. All of the SSRIs, as well as venlafaxine (an SNRI) have been shown to be effective, although the data for fluoxetine are slightly less consistent (Stein and Stein, 2008). With any of these drugs, the onset of action may take up to 6 weeks. Medication is usually continued for at least 6 months and often for longer, because the risk of relapse is high if medication is discontinued after an acute response (Donovan et al., 2010). When medication is reduced, this should be done slowly.

Other drugs. The monoamine oxidase inhibitor, phenelzine, is more effective in the treatment of social phobia than placebo. Moclobemide, the reversible inhibitor of monoamine oxidase, can also be prescribed, but reported response rates vary, and in some studies the drug was not effective (Stein et al., 2004). Benzodiazepines are effective and can be used for short-term relief of symptoms, but should not be prescribed for long because of the risk of dependency (see p. 518). The main use of benzodiazepines is to help patients to cope with essential social commitments while waiting for another treatment to take effect. Beta-adrenergic blockers such as atenolol may achieve short-term control of tremor and palpitations, which can be the most handicapping symptoms of specific social phobias such as performance anxiety among musicians. It is uncertain whether beta-adrenergic blockers are more generally effective in social phobia (Baldwin et al., 2005). There are also positive controlled trials of the antidepressant mirtazapine and the anticonvulsants pregabalin and gabapentin.

For a review of the treatment of social phobia, see Stein and Stein (2008).

Management

What patients need to know. Patients need to understand that although constitutional factors may play a part, the extent and severity of their social anxiety are a result of adopting maladaptive ways of thinking and behaving when they are socially anxious. These patterns of thinking and behaviour can be reversed either with psychological treatment or with medication. Self-help books can inform patients and help them to use simple cognitive–behavioural approaches while awaiting further help.

The choice of treatment. The choice between medication and psychological treatment should be discussed with the patient, after explaining the side-effects of the medication and the need to take it for several months, and in the case of psychological treatment the requirement for regular attendance and strong involvement. The effects of psychotherapy may take longer to become apparent than the effects of medication, but may be longer lasting (Stein and Stein, 2008).

The choice of medication. Benzodiazepines should be used only for short-term relief of symptoms while other treatment takes effect. If there is comorbid substance abuse, benzodiazepines should not be used. In general, one of the SSRIs is likely to be the first choice of medication. If psychological treatment is chosen, cognitive–behaviour therapy is supported by the strongest evidence of effectiveness. Psychodynamic treatment may help some patients, but its use is not based on evidence from clinical trials.

Agoraphobia

Clinical features

Agoraphobic patients are anxious when they are away from home, in crowds, or in situations that they cannot leave easily. They avoid these situations, feel anxious when anticipating them, and experience other symptoms. Each of these features will now be considered in turn.

Anxiety

The anxiety symptoms that are experienced by agoraphobic patients in the phobic situations are similar to those of other anxiety disorders (see Table 9.1), although two features are particularly important:

• panic attacks, whether in response to environmental stimuli or arising spontaneously

• anxious cognitions about fainting and loss of control.

In DSM-IV, cases of agoraphobia with more than four panic attacks in 4 weeks are not classified as agoraphobia but as panic disorder with secondary agoraphobic symptoms.

Situations

Many situations provoke anxiety and avoidance. They seem at first to have little in common, but there are three common themes, namely distance from home, crowding, and confinement. The situations include buses and trains, shops and supermarkets, and places that cannot be left suddenly without attracting attention, such as the hairdresser’s chair or a seat in the middle row of a theatre or cinema. As the condition progresses, the individual increasingly avoids these situations until in severe cases they may be more or less confined to their home. Apparent variations in this pattern are usually due to factors that reduce symptoms for a while. For example, most patients are less anxious when accompanied by a trusted companion, and some are helped even by the presence of a child or pet dog. Such variability in anxiety may suggest erroneously that when symptoms are severe they are being exaggerated.

Anticipatory anxiety

This is common. In severe cases anticipatory anxiety appears hours before the person enters the feared situation, adding to their distress and sometimes suggesting that the anxiety is generalized rather than phobic.

Other symptoms

Depressive symptoms are common. Sometimes these are a consequence of the limitations to normal life caused by anxiety and avoidance, while in other cases they seem to be part of the disorder, as in other anxiety disorders. Depersonalization can also be severe.

Onset and course

The onset and course of agoraphobia differ in several ways from those of other phobic disorders.

Age of onset. In most cases the onset occurs in the early or mid-twenties, with a further period of high onset in the mid-thirties. In both cases this is later than the average ages of onset of simple phobias (childhood) and social phobias (mostly the teenage years).

Circumstances of onset. Typically the first episode occurs while the person (more often a woman; see below) is waiting for public transport or shopping in a crowded store. Suddenly they become extremely anxious without knowing why, feel faint, and experience palpitations. They rush away from the place and go home or to hospital, where they recover rapidly. When they enter the same or similar surroundings, they become anxious again and make another hurried escape. However, not all patients describe such an onset starting from an unexplained panic attack. It is unusual to discover any serious immediate stress that could account for the first panic attack, although some patients describe a background of serious problems (e.g. worry about a sick child), and in a few cases the symptoms begin soon after a physical illness or childbirth.

Subsequent course. The sequence of anxiety and avoidance recurs during the subsequent weeks and months, with panic attacks experienced in a growing number of places, and an increasing habit of avoidance develops.

Effect on the family. As the condition progresses, agoraphobic patients become increasingly dependent on their partner and relatives for help with activities, such as shopping, that provoke anxiety. The consequent demands on the partner often lead to relationship difficulties. Alternatively, the partner may become over-involved in supporting the patient, and difficulties in relinquishing this role may complicate efforts at treatment.

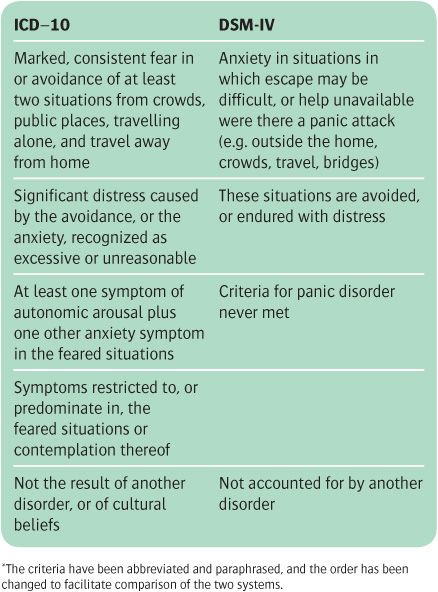

Diagnostic conventions

Most, but not all, patients with agoraphobia have panic attacks, which may be situational or spontaneous, and many of these individuals meet the criteria for panic disorder as well as for agoraphobia. In ICD-10, conditions that meet both sets of criteria are diagnosed as agoraphobia, but in DSM-IV they are diagnosed as panic disorder with agoraphobia. Another difference is that the ICD-10 criteria require definitive anxiety symptoms (see Table 9.6). Whether agoraphobia should be seen as an independent disorder, separate from panic disorder, is disputed (Wittchen et al., 2010). The criteria for the diagnosis of panic disorder in DSM-IV are discussed on p. 195.

Table 9.6 Abbreviated diagnostic criteria for agoraphobia in ICD-10 and agoraphobia without panic in DSM-IV*

Differential diagnosis

Social phobia

Some patients with agoraphobia feel anxious in social situations, and some people with social phobia avoid crowded buses and shops where they feel under scrutiny. Detailed enquiry into the current pattern of avoidance and also the order in which the two sets of symptoms developed will usually decide the diagnosis.

Generalized anxiety disorder

When the agoraphobia is severe, anxiety may develop in so many situations that the condition resembles generalized anxiety disorder. In these cases, the history of development of the disorder will usually point to the correct diagnosis.

Panic disorder

Agoraphobia often includes panic attacks. The distinction between the two disorders has been discussed above.

Depressive disorder

Agoraphobic symptoms can occur in a depressive disorder, and many agoraphobic patients have depressive symptoms. Enquiry about the order in which the symptoms developed will usually point to the correct diagnosis. Sometimes a depressive disorder develops in a person with long-standing agoraphobia, and it is important to identify such cases and treat the depressive disorder (see below).

Paranoid disorders

Occasionally a patient with paranoid delusions (arising in the early stages of schizophrenia or in a delusional disorder) avoids going out and meeting people in shops and other places. The true diagnosis is usually revealed by a thorough mental state examination, which generally uncovers delusions of persecution or of reference.

Epidemiology

A recent community investigation in Europe, using strict DSM-IV criteria, estimated a lifetime prevalence of agoraphobia without panic of 0.6%. However, minor variations in the diagnostic criteria increased the incidence to 3.4%. In the same study, the lifetime prevalence of panic disorder without agoraphobia was estimated to be 1.5%, while the estimated rate of panic disorder with agoraphobia was 1.9% (Wittchen et al., 2008). In clinical samples, agoraphobia without panic appears to be rare, but in the community it may well be more frequent (Wittchen et al., 2010).

Aetiology

Theories of the aetiology of agoraphobia have to explain both the initial anxiety attack and its spread and recurrence. These two problems will now be considered in turn.

Theories of onset

Agoraphobia begins with anxiety in a public place—generally, but not always, as a panic attack. There are three explanations for the initial anxiety.

• The cognitive hypothesis proposes that the anxiety attack develops because the person is unreasonably afraid of some aspect of the situation or of certain physical symptoms that are experienced in the situation (see the section on panic disorder). Although such fears are expressed by people with established agoraphobia, it is not known whether they were present before the onset.

• The biological theory proposes that the initial anxiety attack results from chance environmental stimuli acting on an individual who is constitutionally predisposed to over-respond with anxiety. There is some evidence for a genetic component to this predisposition, in that relatives of probands with agoraphobia are at increased risk of experiencing an anxiety disorder themselves. There has been disagreement as to whether the liability to agoraphobia and panic might be transmitted separately, but it seems likely that these disorders share a common genetic diathesis (Mosing et al., 2009).

• The psychoanalytic theory essentially proposes that the initial anxiety is caused by unconscious mental conflicts related to unacceptable sexual or aggressive impulses which are triggered indirectly by the original situation. Although this theory has been widely held in the past, it has not been supported by independent evidence.

Theories of spread and maintenance

Learning theories. Conditioning could account for the association of anxiety with increasing numbers of situations, and avoidance learning could account for the subsequent avoidance of these situations. Although this explanation is plausible and is consistent with observations of learning in animals, there is no direct evidence to support it.

Personality. Agoraphobic patients are often described as dependent, and prone to avoiding rather than confronting problems. This dependency could have arisen from overprotection in childhood, which is reported more often by agoraphobic individuals than by controls. However, despite such retrospective reports, it is not certain that the dependency was present before the onset of the agoraphobia.

Family influences. Agoraphobia could be maintained by family problems, and clinical observation suggests that symptoms are sometimes prolonged by overprotective attitudes of other family members, but this feature is not found in all cases.

Prognosis

Although short-lived cases may be seen in general practice, agoraphobia that has lasted for 1 year generally remains for the next 5 years, and usually the illness runs a chronic course. Brief episodes of depression are common in the course of chronic agoraphobia, and clinical experience suggests that people are more likely to seek help during these episodes (Wittchen et al., 2010).

Treatment

Much of the available treatment has been developed for panic disorder and for panic disorder with agoraphobia probably because, as noted above, patients with agoraphobia without panic are not common in clinical samples.

Psychological treatment

Exposure treatment was the first of the behavioural treatments for agoraphobia. It was shown to be effective, but more so when combined with anxiety management (see p. 581).

Cognitive–behaviour therapy for panic and agoraphobia is described on p. 584. Clinical trials (reviewed under panic disorder on pp. 197–8) indicate that, in the short term, cognitive therapy is about as effective as medication, and that in the long term it is probably more effective.

Medication

The drug treatment of agoraphobia resembles that for panic disorder (see p. 197), except that medication is usually combined with repeated practice in re-entering situations that are feared and avoided. This exposure may account for some of the observed change. Most studies of drug treatment include both agoraphobic and panic disorder patients, and it is difficult to separate the treatment response of the two disorders. The following account should be read in conjunction with the discussion of medication for panic disorder on p. 197.

Anxiolytic drugs. Benzodiazepines may be used for a specific, short-term purpose such as helping a patient to undertake an important engagement before other treatment has taken effect. Anxiolytic drugs should not be prescribed for more than a few weeks because of the risk of dependence (see p. 518). Indeed, guidelines issued by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2010a) for panic disorder and agoraphobia suggest that benzodiazepines should not be used at all, because they may worsen the long-term outcome of the condition. However, in some countries, although seldom in the UK, the high-potency benzodiazepine, alprazolam, is used to treat agoraphobia with frequent panic attacks. Some authorities believe that short-term benzodiazepine treatment does have a role in panic disorder—for example, while the patients is being established on more suitable drug treatment (Roy-Byrne et al., 2006). However, it is possible that benzodiazepines could impair the response to psychological treatments (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2010a).

Antidepressant drugs. As well as the obvious use to treat a concurrent depressive disorder, antidepressant drugs have a therapeutic effect in agoraphobic patients who are not depressed but who have frequent panic attacks. Imipramine was one of the first agents to be used in this way, but similar effects have been reported with clomipramine. The treatment regime is the same as that described for panic disorder on p. 197. In addition, several SSRIs and venlafaxine have been shown to be effective in panic disorder with and without agoraphobia (see p. 197 and Baldwin et al., 2005). SSRIs are generally recommended as the most suitable first-line treatment because of their safety and tolerability relative to tricyclic antidepressants (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2010a). As with other drug treatments for anxiety, maintaining the medication for several months after a clinical response has been obtained significantly lowers relapse rates (Donovan et al., 2010).

Management

What patients need to know. Patients with agoraphobia and those around them usually have difficulty in understanding the nature of agoraphobia, and may think of it as the result of lack of determination to overcome normal anxiety. A two-stage explanation, starting with the panic attacks, is generally helpful. Panic attacks can be likened to false alarms occurring in an over-sensitive intruder-alarm system. The excessive sensitivity can be explained in terms of constitution or chronic stress, whichever fits the patient’s history. Avoidance can be explained in terms of conditioning, with examples such as anxiety after falling from a bicycle or following a car accident. Partners, friends, and relatives can usually understand the principles of behaviour therapy, but may be unsympathetic to drug treatment and puzzled when antidepressants are prescribed for anxiety. In response the patient can say that the medication is to reduce the sensitivity of the ‘alarm system’, and explain that some antidepressant drugs can do this.

Patients also need to know that medication is only likely to be effective if accompanied by determined and persistent efforts to overcome avoidance. The therapist should explain how to do this, but must emphasize that the result will depend on the patient’s own efforts. Self-help books (see below) are a useful source of information about the disorder and about the ways in which people with agoraphobia can help themselves.

Behavioural management. In early cases, the patient should be strongly encouraged to return to the situations that they are avoiding. The treatment of choice for established cases is probably a combination of exposure to phobic situations with cognitive therapy for panic attacks (see p. 584). If there is a waiting list for cognitive therapy, the referring clinicians should supervise exposure treatment. Several self-help manuals have been published which reduce the time that therapists need to spend in doing this.

Medication can be offered as a first treatment, especially when panic attacks are frequent and/or severe. However, it needs to be accompanied by repeated exposure to previously feared and avoided situations. In the UK, the medication is usually an antidepressant, generally an SSRI. Any medication that has proved beneficial should be discontinued gradually.

Patients who have relapsed after drug treatment can be offered behaviour therapy, although no controlled trials have been carried out specifically with such individuals. Most patients improve, but few of them lose the symptoms completely following treatment. Relapse is common, and patients should be encouraged to seek further help at an early stage should relapse occur.

Panic disorder

Although the diagnosis of panic disorder did not appear in the nomenclature until 1980, similar cases have been described under a variety of names for more than a century. The central feature is the occurrence of panic attacks. These are sudden attacks of anxiety in which physical symptoms predominate, and they are accompanied by fear of a serious medical consequence such as a heart attack.

In the past, these symptoms have been variously referred to as irritable heart, Da Costa’s syndrome, neurocirculatory asthenia, disorderly action of the heart, and effort syndrome. These early terms assumed that patients were correct in fearing a disorder of cardiac function. Some later authors suggested psychological causes, but it was not until the Second World War (when interest in the condition revived) that Wood (1941) showed convincingly that the condition was a form of anxiety disorder. From then until 1980, patients with panic attacks were classified as having either generalized or phobic anxiety disorders.

In 1980, the authors of DSM-III introduced the new diagnostic category, panic disorder, which included patients whose panic attacks occurred with or without generalized anxiety, but excluded those whose panic attacks appeared in the course of agoraphobia. In DSM-IV, all patients with frequent panic attacks are classified as having panic disorder, whether or not they have agoraphobia (agoraphobia without panic attacks has a separate rubric; see p. 192). Panic disorder is included in ICD-10. However, unlike DSM-IV, the diagnosis is not made when panic attacks are accompanied by agoraphobia.

Clinical features

The symptoms of a panic attack are listed in Table 9.7. Not every patient has all of these symptoms during the panic attack, and for a diagnosis of panic disorder DSM-IV requires the presence of only four or more symptoms. The important features of panic attacks are that:

• anxiety builds up quickly

• the symptoms are severe

• the person fears a catastrophic outcome.

Some people with panic disorder hyperventilate, and this adds to their symptoms.