(Video 19.1). Other findings include muscle weakness with greater than normal tone. Dysphagia may also occur. In addition to spastic dysarthria, the patient with pseudobulbar palsy may often exhibit emotional lability and may exhibit spontaneous outbursts of laughter or crying known as “pseudobulbar affect.” Spastic dysarthria may also result from ischemic insults. Isolated or “pure” dysarthria results mainly from small subcortical infarcts involving the internal capsule or corona radiata. Isolated dysarthria, with facial paresis, is considered a variant of the dysarthria-clumsy hand lacunar syndrome. Occasionally, an isolated small subcortical infarct will interrupt the corticolingual fibers from the motor cortex, causing dysarthria without hemiparesis. Other common causes of spastic dysarthria include tumor, traumatic brain injury, spastic cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis (MS), and ALS.

C. Mixed dysarthria is caused by simultaneous damage to two or more primary motor components of the nervous system, involving both UMNs and LMNs. This form of dysarthria is common in patients with MS, ALS, or severe traumatic brain injury. The patients may speak very slowly and with great effort. Articulation is markedly impaired with imprecise articulation and hypernasality. Vocal pitch is low with harsh and/or strained, or strangled vocal quality. Prosody is disrupted with intonation errors and inappropriately shortened phrases/sentences. Bulbar involvement in ALS often presents in this fashion with dysarthria, hypophonia, drooling of saliva, and progressive swallowing difficulties (Fig. 19.1).

FIGURE 19.1 Diffuse tongue atrophy and fasciculations in a patient with bulbar motor neuron disease.

D. Ataxic dysarthria is usually associated with cerebellar disorders with articulation and prosody most impaired. Patients present with decreased motor coordination for accurate articulation with slow and deliberate articulation, imprecise consonant production, distorted vowel production, and prolonged phonemes. Equal and excessive stress is placed on all syllables. Ataxic dysarthria is caused by damage to the cerebellum, or cerebellar connections to other parts of the brain. Isolated cerebellar dysarthria has also been reported with small infarcts in the left paravermian zone of the ventral cerebellum (lobulus simplex and semilunaris superior).

E. Hypokinetic dysarthria, most typically seen in parkinsonism, is associated with hypophonia or reduced vocal loudness. Furthermore, there is monotonous speech with a slow and flat rhythm. Initiation of speech is difficult, resulting in inappropriate silences intermixed with short rushes of speech. The rate is variable with wide fluctuations in pitch.

F. Hyperkinetic dysarthria also results from secondary to damage to the basal ganglia and is typified by Huntington’s disease. Damage to this system causes involuntary movements such as tremors, dyskinesia, athetosis, and dystonia. Vocal quality may be described as harsh, strained, or strangled and is often associated with spasmodic dysphonia.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The major clinical distinctions are between dysarthria, dysphonia, apraxia, and aphasia. Both dysarthria and apraxia are motor speech disorders, and it may be sometimes difficult to differentiate among them. Apraxia of speech is a motor programming or planning disorder involving speech production tasks. Automatic and involuntary tasks are usually spared. Errors in articulation are inconsistent and are associated primarily with vowel and consonant distortions. Initiation is difficult with obvious effortful groping in attempts by the patient to achieve accurate movement of the articulators. Patients are often aware of the errors and make specific attempts at correcting the errors. However, the patients are often unsuccessful in achieving initial articulatory configurations or transitioning from one sound to the next.

Aphasia is a loss or impairment of language production and/or comprehension, often accompanied by a loss of ability to read and/or write, whereas dysarthria is a problem in speech articulation. It is not uncommon for aphasia and dysarthria to coexist. A person with aphasia may be able to communicate with adequate breath support, voicing, and articulation, but may be unable to comprehend other persons or name, repeat, or express themselves adequately. Patients may also have isolated anomia (word-finding difficulty) with inability to state certain words or name specific persons or objects.

Dysphonia is a term that describes voice disorders. It is a characteristic of certain types of dysarthria. Dysphonia, however, may stand alone when describing other voice disorders. Spasmodic dysphonia is a specific type of neurologic voice disorder that involves involuntary tightening or constriction of the vocal cords, causing interruptions of speech and affecting the voice quality, which can be strained or strangled.

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

A detailed history and thorough neurologic examination are essential to determine the possible etiology of the different types of dysarthria. The presenting symptoms, duration, pattern of speech disturbance, and progression of symptoms may help elucidate the mechanism and etiology of dysarthria. In particular, acute onset of symptoms would suggest a possible stroke as the basis of the dysarthria, but one should avoid diagnostic closure and always consider alternative diagnostic explanations for dysarthria. Concomitant neurologic symptoms, medical comorbidities, and knowledge of contributory medications or exposures may all help determine the etiology of the dysarthria. A complete examination is necessary to determine the nature of dysarthria; for example, patients with extrapyramidal disorders have slow, quiet, and monotonous speech, which is gradually progressive and is typically associated with rigidity, bradykinesia, falls associated with postural instability, and characteristic tremors. Scanning speech with dysprosody is often suggestive of a cerebellar disorder, especially when incoordination and gait unsteadiness are present. Patients with an LMN lesion may have pronounced tongue atrophy and fasciculations, with gradual and progressive muscle weakness, whereas an UMN disease is characterized by spastic and explosive speech. Palatal palsy and decreased gag reflex with tongue weakness may indicate bulbar involvement, whereas a brisk jaw jerk, hyperactive gag reflex, and emotional lability are suggestive of pseudobulbar palsy. Mechanical factors contributing to dysarthria include pharyngeal, vocal cord, tracheal, and other airway lesions. Trauma and space-occupying masses in these areas must also be considered.

Neuroimaging studies of the head or neck may be helpful in diagnosing central and peripheral causes (see Chapter 35) with magnetic resonance imaging with contrast enhancement as the preferred modality. Electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies may be an important tool in the diagnosis of motor neuron disease, peripheral nerve injury or focal dystonia, polyneuropathy, myopathy, or neuromuscular junction disorders such as MG or the Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) (see Chapter 36). Repetitive nerve stimulation or single-fiber EMG to help diagnose neuromuscular junction syndromes should be considered in appropriate cases, and EMG of facial, pharyngeal, or tongue muscles may sometimes be useful in elucidating the mechanism of dysarthria. Lumbar puncture and cerebrospinal fluid analysis are discussed in Chapter 33. Pulmonary function testing may be helpful to assess respiratory function and coordination associated with sound production. Specialized serum studies may also be indicated to identify the underlying etiology of dysarthria (for example, serum antibody panels may help diagnose MG or LEMS).

EVALUATION OF SPEECH FUNCTION

In the evaluation of speech disorders, a speech–language pathologist (SLP) is often consulted to differentiate various types of dysarthria and help determine treatment strategies. Several core components are included in the evaluation. The SLP, after reviewing the neurologic and medical evaluation, conducts an interview with the patient and/or caregiver. This interview helps to further define the time of onset, pattern of symptoms, previous assessments completed or treatment received, and the course of symptom improvement of the dysarthria over time.

An examination of the physical structures of the speech mechanism, as well as assessment of articulation, respiration, phonation, resonance, and prosody is performed. This includes a thorough oral mechanism examination to assess strength, rate of movement, range of motion, and coordination of the speech mechanism including the jaw, lips, tongue, and velopharyngeal function. Deviations from the norm give way to articulation errors. Articulation can further be assessed in diadochokinetic rate and by listening to a brief speech sample. Abnormalities are noted with the production of imprecise consonants, producing voiced for voiceless syllables, repeated or prolonged phonemes, or vowel distortions. Speech intelligibility can be rated as well. With decrease in laryngeal control, a patient may be unable to produce voiceless syllables. Abnormalities in respiration are often observed in sustained phonation tasks. A patient may be unable to sustain a vowel, such as “ah,” with normal loudness. Verbal output may also be limited to single words or short phrases due to a lack of expiratory effort. Vocal quality may be breathy, and a patient may be unable to maintain voicing throughout the length of a phrase or sentence. Voicing may start strong, but gradually fade with increased phrase or sentence length.

Appropriate phonation is dependent on adequate respiration. Adequate breath support is required to achieve functional vocal fold vibration for phonation. Abnormalities in voicing may be attributed to unilateral or bilateral vocal fold (cord) paralysis, a vocal cord mass, or vocal cord edema. Vocal fold adduction may be compromised resulting in a breathy vocal quality (hypofunction). Excessive adduction of the vocal folds gives way to possible strained or strangled output in addition to increased pitch (hyperfunction). If there is a suspicion of an abnormal approximation of the vocal folds, an ear-nose-and-throat (ENT) specialist consultation should be considered. Assessment of phonation includes sustained phonation tasks. Having the patient sustain a vowel (“ah” or “ee”) for as long as they can allows the SLP to discriminate between variations in pitch, breath support, loudness, and voice quality. Of note, measuring maximum length of phonation provides limited direction in differentiating among dysarthria’s because sustained phonation is not characteristic of functional conversational speech.

Hypernasality and hyponasality are characterized by abnormalities in resonance. Hypernasality may be evidenced by an excess escape of air into the nasal cavity resulting from reduced velopharyngeal closure or soft palate weakness. It is also important to watch the soft palate at rest, and during sustained phonation, for functional movement or possible fatigue. Hyponasality results from inadequate velopharyngeal opening, which may be caused from a complete or partial blockage of nasal airway. If a blockage is suspected, further ENT evaluation may be required. Prosody can be analyzed by assessing the coordination of respiration, phonation, and articulation. Errors in prosody may present as abnormally slowed or rapid rate of speech, decreased stress or emphasis patterns, intonation errors, or inappropriately shortened phrases/sentences that can be mixed with intervals of silence. Prosody can be assessed within the speech sample or by having the patient imitate various phrases. One sample of stress or intonation variations is “Is THAT your car?”, “Is that YOUR car?”, and “Is that your CAR?” Clearly, varying the stress/intonation within this short sentence may result in significant changes in the meaning of a sentence.

Impairments to any of the above-listed speech mechanisms resulting in dysarthria often coexist with dysphagia. Current standards require that dysphagia screening be documented on all stroke patients; dysphagia screening should be done on all patients with dysarthria, however. Dysphagia is frequently present with dysarthria in patients with extrapyramidal, motor neuron, or neuromuscular disorders. If dysphagia is noted with a brief swallow screening, a formal swallow evaluation is indicated, and should include a thorough history for possible dysphagia and assessment of oral mechanisms for strength, movement, and coordination of the muscles for swallowing. If then deemed safe, the patient is given various consistencies of liquids and/or solids, and tolerance to the various samples is observed and evaluated. The SLP, through observation and hands-on assessment, notes oral, pharyngeal, and sometimes esophageal difficulties. Depending upon the clinical results of the bedside exam, the SLP may recommend oral feeding with the least-restrictive liquids and/or solids, a video fluoroscopic swallow evaluation, or both. When indicated, a fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing may also be helpful for the assessment of swallowing function as well as actual movement of the vocal cords and tracheopharygneal muscles involved in the mechanics of swallowing and speech production.

MANAGEMENT

The underlying etiology of the dysarthria type and overall prognosis for improvement must be taken into careful consideration when devising a treatment plan for the dysarthria. Treatment of the underlying condition (i.e., drugs for neuromuscular or extrapyramidal disorders) will often result in improvement in dysarthria. Treatment also includes patient and family education, and training, about compensatory strategies. Treatment of respiratory/phonatory deficits may include improving breath support to increase vocal volume. Slowing the rate of speech may be necessary to improve articulation and intelligibility. Nonspeech oral-motor training may be recommended for strengthening muscles and increasing mouth, tongue, and lip range of motion and movement. Changes in loudness and prosody, through intonation and stress patterning tasks, may be targets of intervention as well. In severe cases, augmentative and alternative communication devices, such as computerized voice production systems, may be needed.

Key Points

• Normal speech occurs with smooth coordination of respiration, phonation, articulation, resonance, and prosody.

• Components of dysarthria may include slurred speech, slow or rapid speech, whispering speech, abnormal intonation, and changes in vocal quality.

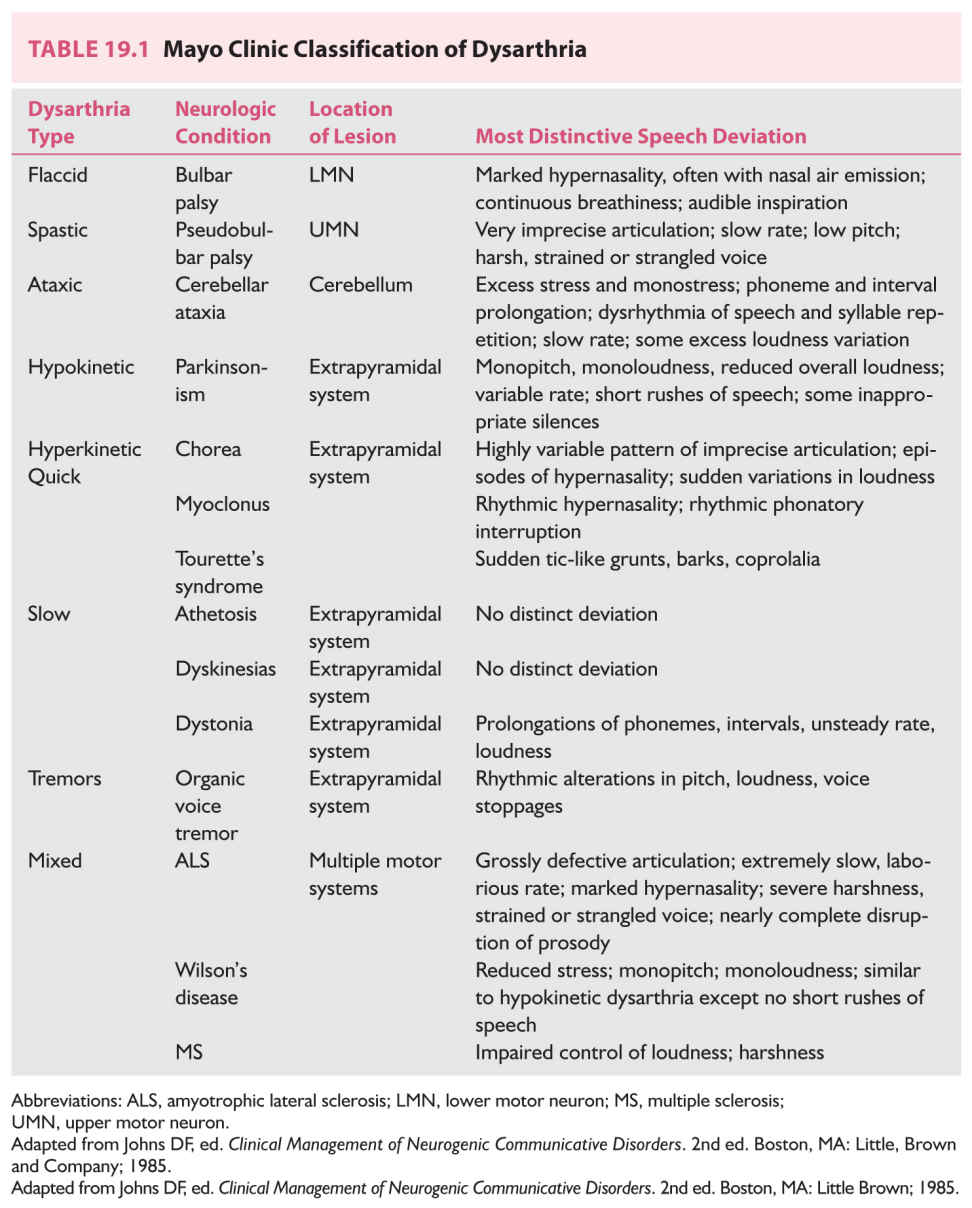

• Six major types of dysarthria have been described: flaccid, spastic, mixed, ataxic, hypokinetic, and hyperkinetic.

• Identification of the underlying cause of dysarthria is imperative; treating the cause will often result in improvement of dysarthria.

• Consider dysphagia screening for all patients with dysarthria, regardless of etiology.

• Speech–language therapy is an integral part of dysarthria treatment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree