A. In cases of immediate failure, the patients never improve after surgery. This universally implies an error in diagnosis or a technical deficiency with the surgery. After the protocol outlined in sections Nonsurgical Modalities and Pain Management has been implemented, these patients require MRI with and without contrast material. The prognosis for these patients is very good when an error is identified. If no deficiency is found, the outcome is considerably more discouraging. Surgery has no role in those cases.

B. The next group of failures manifests days to weeks after surgery. It is quite common, however, for patients who have initial improvement postoperatively in the hospital to experience a setback as they become more active on arriving home. This is a normal although not universal finding and is best managed expectantly. Patients who experience initial improvement and then experience clear deterioration need a more deliberate evaluation. These cases can represent recurrent disk herniation, iatrogenic instability, or sagittal imbalance. The physical examination and pain signature favor one diagnosis over the other. Recurrent nerve-root compression is best evaluated with MRI with and without contrast material. Instability should be evaluated with CT to assess the bony removal, and dynamic plain radiographs. Standing long cassette studies in both the coronal and sagittal plane are required to rule out deformity. In this time frame, some patients have progressive causalgia-type or neuropathic pain. This may result from a prolonged preoperative duration of nerve compression or injury during surgery. This condition is very refractory, although recent success has been reported with gabapentin, pregabalin, and a variety of antidepressants.

C. Another group of failures manifests weeks to months after surgery. The description of clear radiculopathy suggests recurrent herniation. Arachnoiditis manifests most often at this time. Patients often describe back and leg pain, which can be similar to the presenting problem. Classic cases manifest as symptoms of claudication or lower extremity causalgia. CT myelography is the study of choice and typically shows clumping of nerve roots and restricted flow of intrathecal contrast material. Surgery directed at the arachnoiditis is unsuccessful. There has been some success with spinal cord stimulators in these cases. Thankfully, the incidence has decreased dramatically with the advent of water-soluble contrast agents and the relatively infrequent use of myelography in the MRI era.

D. The last group of failures manifests after a pain-free interval of months to years.

1. Many of these cases have developed either iatrogenic lumbar instability because decompression was too wide or lumbar instability caused by the intrinsic disease. The incidence of post-laminectomy spondylolisthesis is somewhere between 2% and 10%. Even simple discectomy has been associated with a 3% incidence of postoperative instability that necessitates subsequent fusion. It has been widely circulated that the medial half of the facet joint can be removed bilaterally without inducing instability. However, this admonishment is not consistent with the fact that the medial half of the joint comprises the descending facet almost exclusively and that removal of the medial half can leave the facet completely incompetent. There is consensus that complete laminectomy and bilateral facetectomy consistently produce instability. In cases in which this extent of resection is needed to accomplish decompression, fusion should be incorporated into the surgical plan.

2. Pseudoarthrosis after lumbar fusion manifests in a time frame similar to that of postlaminectomy spondylolisthesis. In part, the timing of presentation may represent the fact that most spine surgeons are not prepared to give up on a fusion for 9 to 12 months after surgery. There are also no commonly accepted criteria for diagnosis of pseudoarthrosis. Dynamic radiographs often appear normal, and bone scans are equivocal. The incidence of symptomatic pseudoarthrosis after a posterolateral lumbosacral fusion is between 5% and 15%. The cause can be either technical deficiency of the surgery or biologic deficiency of the patient. There is good evidence that smoking negatively affects the rate of fusion. The rate of pseudoarthrosis increases with the number of levels of arthrodesis. The use of BMP, external bone stimulators, and allograft bone graft extenders has decreased the rate of pseudoarthrosis. Hardware implanted in the patient may also become symptomatic during this time frame. The modulus of elasticity of metal rods is 10 to 20 times stiffer than bone, so that even following a successful fusion, these implants may loosen at the bone–implant interface or break. Recent experience suggests that alternate biomaterials, such as PEEK, may be a more suitable implant because of its near-identical stiffness to bone, and resistance to breakage.

RADIOGRAPHIC EVALUATION OF FAILED BACK SYNDROME RADIOGRAPHY PLAYS AN IMPORTANT ROLE IN THE EVALUATION OF FBS

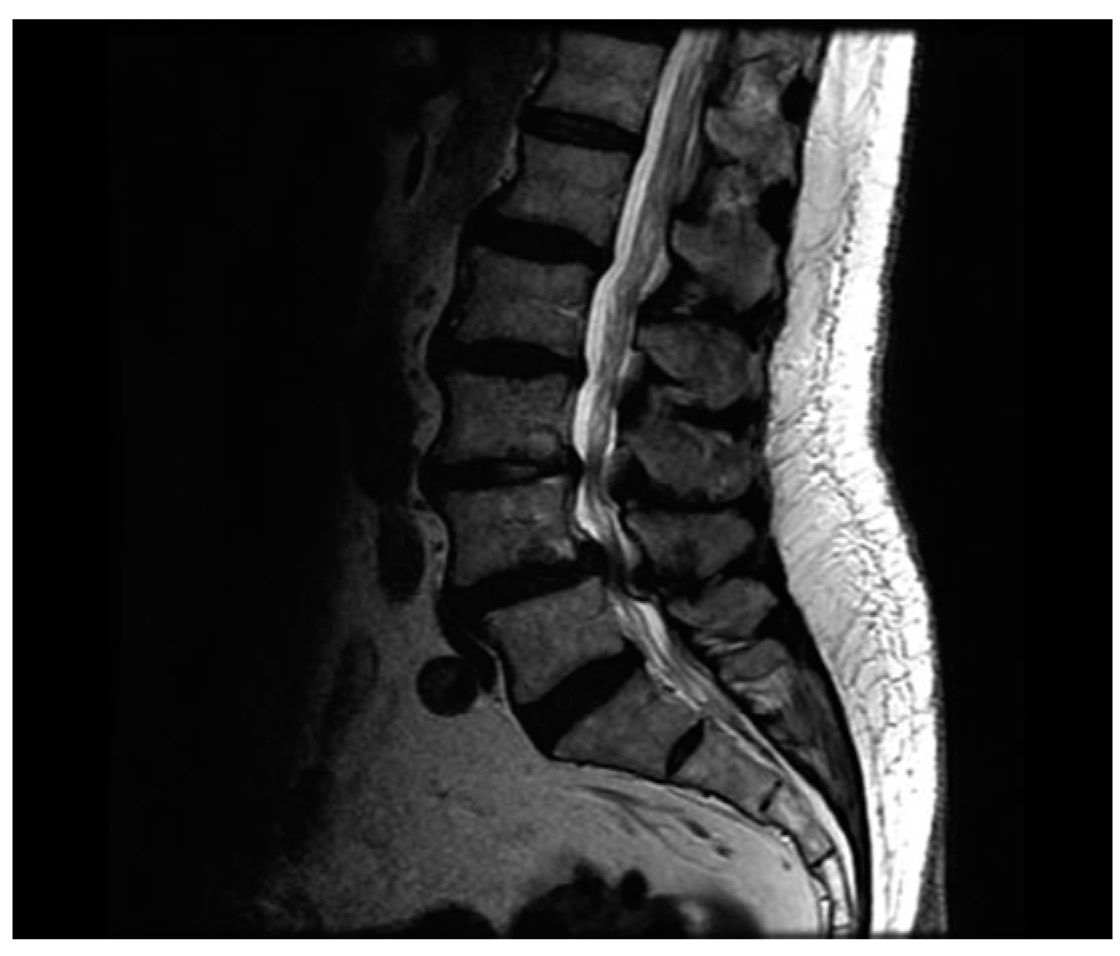

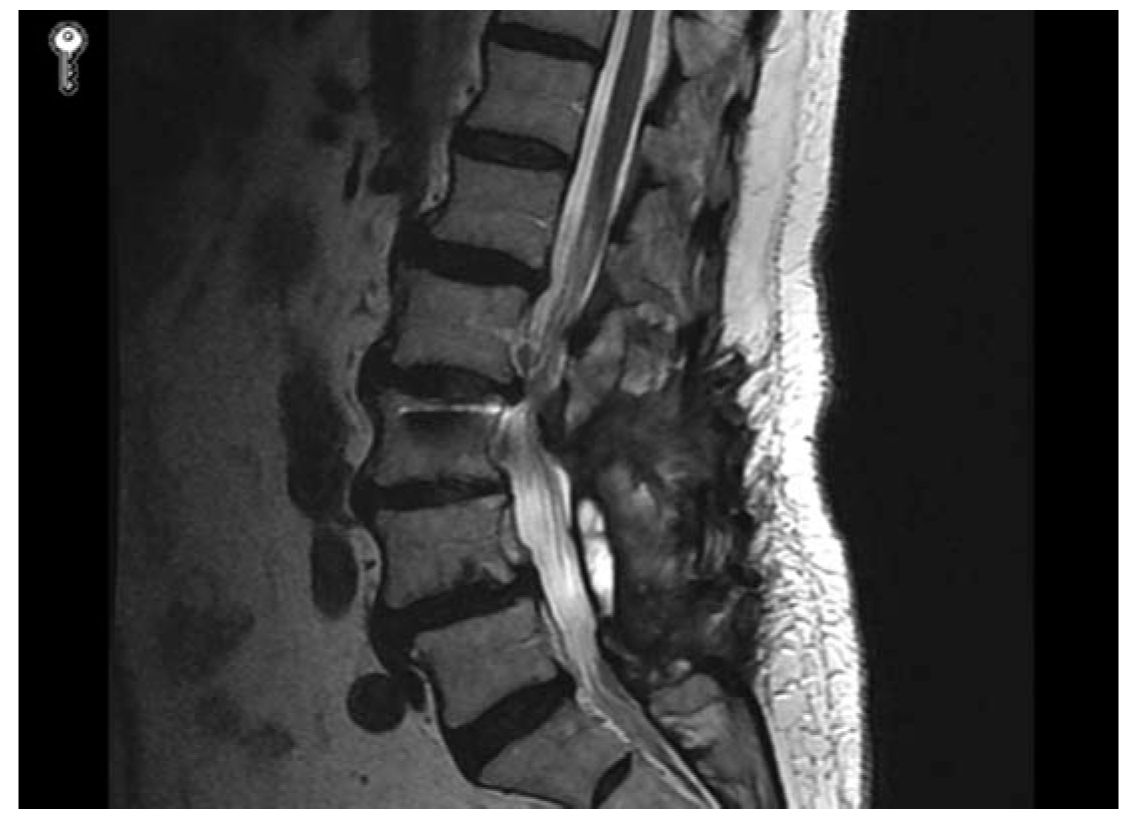

A. In the evaluation of recurrent disk herniation, contrast-enhanced CT or MRI is vital (Figs. 26.1 and 26.2). Postoperative scar becomes homogeneously enhanced. A herniated disk may have some peripheral enhancement, but because it is avascular, the disk does not become centrally enhanced. Although scar and disk can both cause compressive symptoms, surgery to remove scar tissue is rarely successful.

B. Radiographic evaluation of a fusion is more difficult. In short, there is no universally accepted way to assess successful fusion after arthrodesis.

1. Dynamic or flexion and extension radiographs are specific for instability if motion is detected. However, these studies are very insensitive. Fibrous nonunion or the instrumentation itself can prevent the flexion–extension radiographs from appearing abnormal.

2. Plain radiographs can show a robust fusion mass, but it is often impossible to know whether the bony mass is in continuity. Lucency or halos around pedicle screws suggest instability. CT with sagittal and coronal reconstruction can be helpful. Special techniques must be used to minimize artifact of the instrumentation.

3. Bone spectroscopy has been advocated, but this modality is unreliable for at least several years after surgery.

FIGURE 26.1 Preoperative lumbar MRI showing stenosis at L3–L5 with an L4–L5 spondylolisthesis.

FIGURE 26.2 Repeat lumbar MRI obtained 3 years following L3–L5 laminectomies and fusion, and recurrent symptoms. Note junctional stenosis at the L2–L3 level.

4. Three-dimensional CT has been advocated by some authors in the evaluation of FBS. It has the advantage of clearly imaging the bony resection and can clearly delineate the extent of bony fusion.

REFERRALS

A. Referral to a neurologist or spine surgeon is indicated for any patient with a new or progressive neurologic deficit. In the context of FBS and chronic pain, it is important not to miss this dramatic change in the patient’s course.

B. Imaging should be performed only in response to a significant change in the symptoms. When dramatic changes are found at imaging studies, patients with FBS should be reevaluated.

C. Often the job of weaning narcotics is left to an internist or general neurosurgeon. This can be appropriate; however, when reduction goals are not being met and the program becomes stalled, these patients should be referred to specialized centers. Long-term use of narcotic analgesics can be acceptable treatment in some cases, but it should be chosen explicitly, not as an ad hoc default.

D. FBS is a difficult management problem, and all these patients should be seen by a spine surgeon or pain center. In general, patients with FBS should be cared for by a multidisciplinary team. It is important to maintain vigilance in case new important symptoms arise, which may alter the treatment regimen.

Key Points

• FBS typically occurs following lumbosacral surgery.

• Etiology includes initial misdiagnosis, recurrent pathology, new spondylosis or spondylolisthesis at the site of previous surgery or adjacent levels, or pseudoarthrosis.

• Symptoms include radiculopathy, neurogenic claudication, and back pain.

• Evaluation with a combination of CT with or without myelography, MRI and flexion–extension X-rays is required.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree