(Video 23.1)

B. Physical examination.

1. Acute low back pain. Examination of a patient with acute low back pain should begin with inspection and palpation of the low back. Paravertebral muscle spasms may be present. In most cases of mechanical back pain, straight-leg-raise testing causes back pain only. Straight-leg-raise testing that causes back and leg pain suggest root or cauda equina compression. The neurologic examination should include walking on the heels and toes, squatting, and individual testing of the foot and toe dorsiflexors and plantarflexors, the quadriceps, and the iliopsoas muscles. The general examination should include palpation of the abdomen, to rule out an abdominal aortic aneurysm, and a rectal examination.

2. Lumbar disc disease with sciatica. The patient walks in a slow, deliberate manner with slight forward tilt of the trunk. Paravertebral muscle tightness can cause decreased range of motion of the back, and asymmetric muscle tightness can cause associated scoliosis. The patient prefers to stand or lie rather than sit. The best position is usually lying on the unaffected side with the affected leg slightly bent at the knee and hip. The pain is frequently worsened by Valsalva’s maneuver.

a. Straight-leg-raise testing is important in the diagnosis of lumbar disc disease. The patient is in a supine position with the knee extended and the ankle plantar flexed. The examiner raises the leg slowly. Normally, the leg can be raised to 90 degrees without discomfort or with slight tightness in the hamstring. When the nerve root is compressed by a ruptured disc, the straight leg raise is limited and causes back and leg pain. It worsens with dorsiflexion of the foot. In most cases, the result of the straight-leg-raise test is positive only on the side of the disc rupture. If lifting the leg without symptoms causes pain in the leg with symptoms, one must consider disc rupture in the axilla of the nerve root.

b. Motor testing is directed at the nerve roots most commonly affected. Compression of the L5 nerve root can cause foot and great toe dorsiflexion weakness (tibialis anterior and extensor hallucis longus). When the compression is severe, the patient may have foot drop. Compression of the S1 nerve root can cause plantar flexion weakness. This is difficult to detect at the bedside and is best tested by having the patient do toe raises one leg at a time. Weakness at L4 can cause quadriceps weakness. The patient may have the sensation that the leg is giving way. Disease of the L3–L4 disc decreases the knee reflex, and disease of the L5–S1 disc decreases the ankle reflex.

c. Sensory loss resulting from a disc rupture seldom occurs in a dermatomal pattern. Rupture of the L5–S1 disc can cause relative hypalgesia in the bottom of the foot, lateral aspect of the foot, and little toe. Rupture of the L4–L5 disc can cause relative hypalgesia in the dorsum of the foot and great toe. Rupture of the L3–L4 disc can cause sensory loss in the anterior thigh and shin.

3. Lumbar spinal stenosis. Findings at neurologic examination of the lower extremities may be relatively unremarkable at rest. One occasionally may find evidence of mild nerve-root dysfunction such as L5 numbness and weakness.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

A. Acute low back pain.

1. Lumbosacral sprain

2. Facet joint inflammation

3. Degenerative arthritis

4. Fracture (compression if osteoporotic and minimal trauma history)

5. Metastatic disease

6. Primary bone tumor

7. Diskitis

8. Epidural abscess

9. Ankylosing spondylitis

10. Paget’s disease

11. Tethered spinal cord

12. Spondylolisthesis

13. Conversion reaction

B. Lumbar disc disease with sciatica.

1. Ruptured extruded disc

2. Lateral recess and foraminal stenosis

3. Synovial cyst

4. Spondylolisthesis

C. Lumbar spinal stenosis.

1. Congenital stenosis

2. Stenosis secondary to degenerative damage

3. Synovial cyst

4. Peripheral vascular disease. Arterial vascular insufficiency can cause leg discomfort during walking but is relieved by simply stopping rather than bending forward or sitting.

5. Degenerative hip disease can cause limitation of standing and walking. The pain usually comes on with any type of weight-bearing. Examination reveals a decreased range of motion of the hip, and hip rotation may exacerbate the discomfort. The pain associated with degenerative hip disease is most likely to be located in the proximal hip, thigh, and knee.

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

A. Acute low back pain. In the absence of red flags that suggest a more serious disorder, most testing should be delayed for 4 weeks. If the patient does not respond to conservative treatment in 4 weeks, however, the following studies may be considered.

1. Lumbosacral radiographs of the spine.

2. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

3. Computed tomography (CT) scan if MRI is not available or contraindicated, or if the patient is claustrophobic. CT should include L3–L4, L4–L5, and L5–S1.

4. Lumbosacral myelography and postmyelography CT seldom are needed unless it is impossible to perform MRI (pacemaker).

5. Laboratory tests include complete blood cell count (CBC) with differential and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).

6. A bone scan can be done, especially if there is a history of carcinoma.

7. Occasionally a discogram may be done in a patient with refracting back pain, a degenerative disc, and no response to extensive conservative therapy.

B. Lumbar disc disease with sciatica. Few tests are needed in the first 4 weeks if the signs and symptoms are mild to moderate. Severe sciatica and sciatica associated with marked neurologic deficits and weakness of bladder and bowel movements should be evaluated earlier. The presence of a disc rupture on an imaging study does not necessarily imply nerve-root dysfunction. Approximately 75% of adult patients with symptoms have disc bulges or protrusions. Most severe sciatica is associated with disc extrusion.

1. Plain lumbosacral radiographs of the spine should be performed.

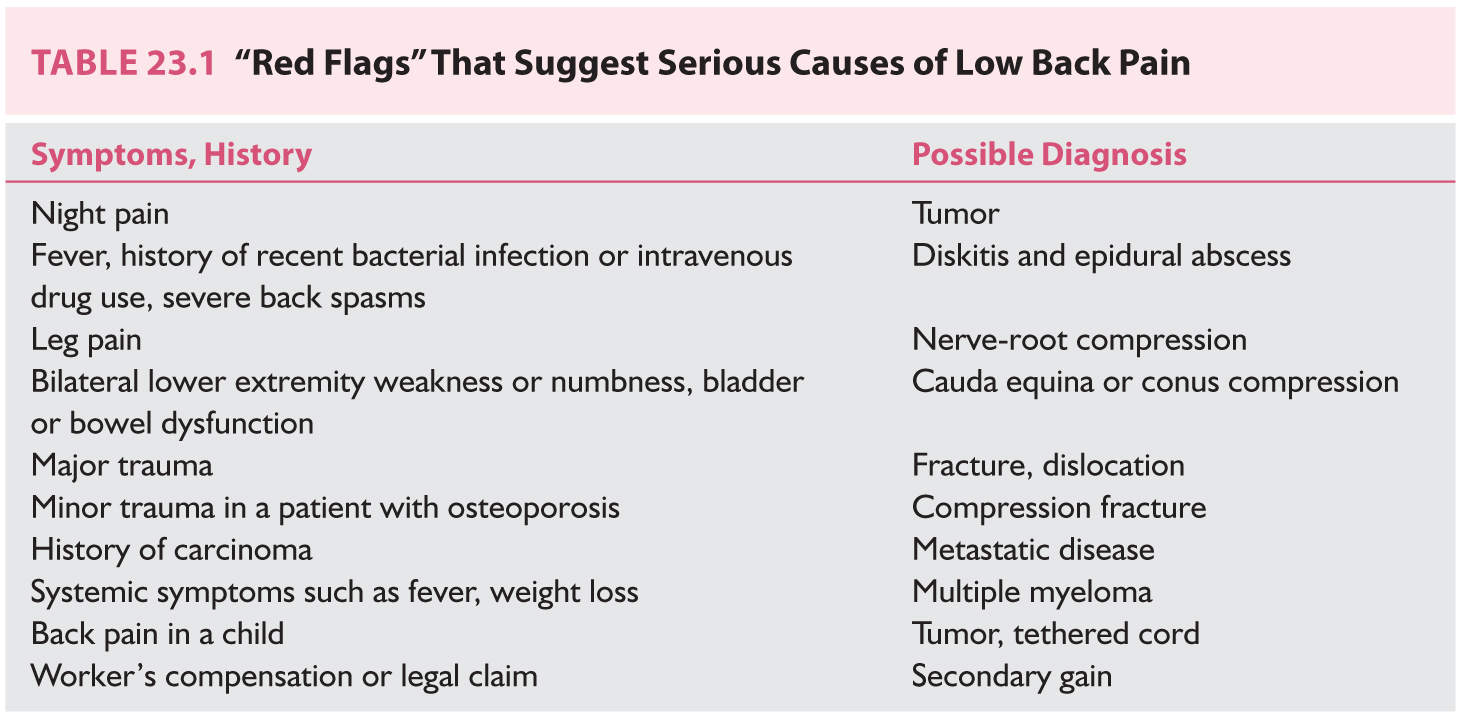

2. MRI is the procedure of choice for evaluating a lumbar disc rupture. L5–S1 disc extrusion causing severe right S1 nerve-root compression is shown in Figure 23.1.

3. CT may be used if the patient is unable to tolerate MRI.

4. Myelography and postmyelography CT can be used occasionally if MRI and CT do not provide enough information for a diagnosis.

5. Diagnostic nerve blocks, if there is doubt about which nerve(s) are involved.

6. Electromyography and nerve conduction velocity studies may be helpful if the signs and symptoms do not correlate well with the MRI or CT findings and if one suspects a peripheral nerve problem.

C. Lumbar spinal stenosis. Unless the symptoms are severe, testing may not be done in the early stages of spinal stenosis. A patient who seeks medical therapy for spinal stenosis usually has a walking tolerance of <1 to 2 blocks and a standing tolerance of 20 minutes or less.

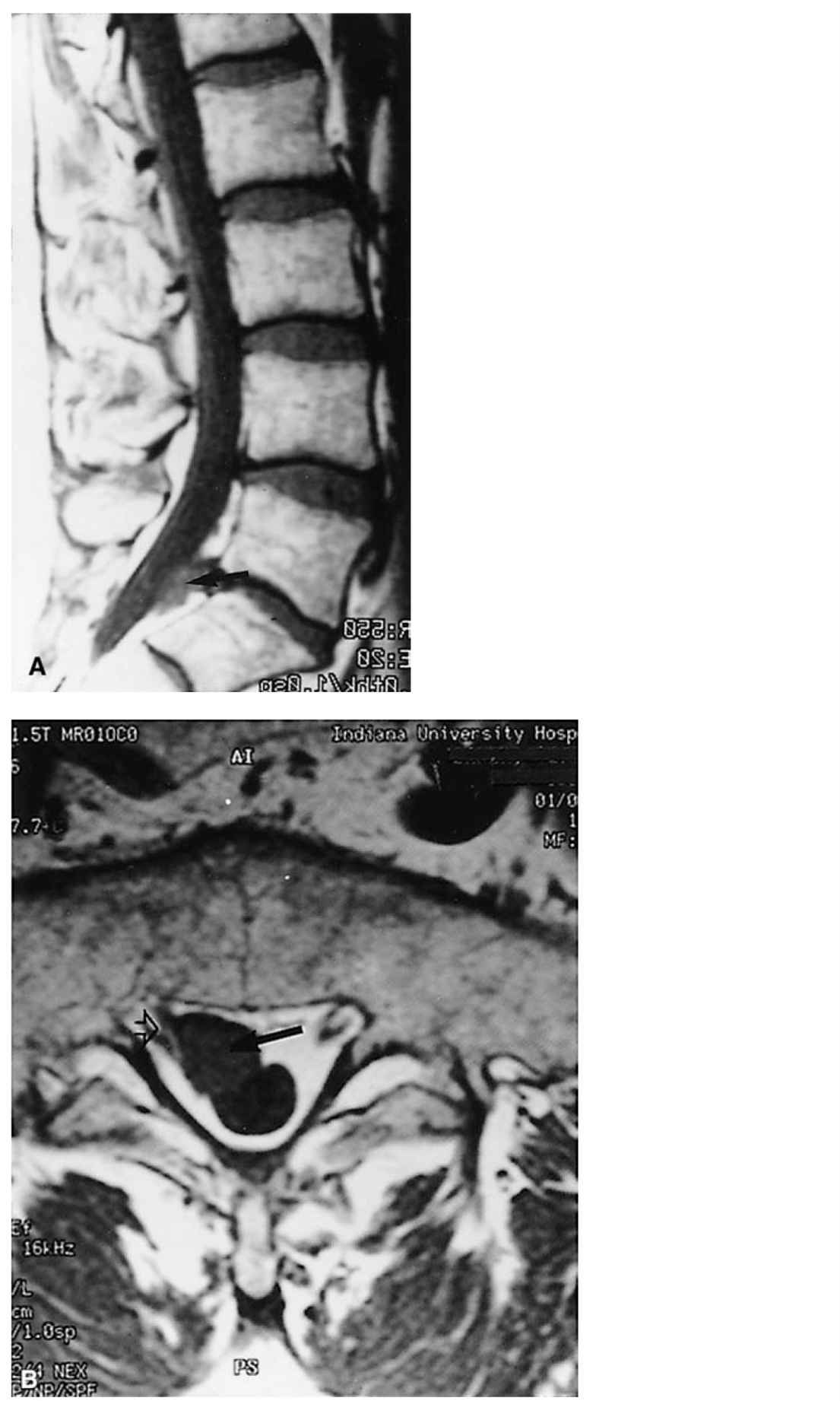

1. Plain radiographs of the lumbosacral spine are indicated to assess the degree of degenerative change and bone density. Flexion–extension lateral views are needed to detect degenerative spondylolisthesis (Fig. 23.2). Degenerative spondylolisthesis is frequently associated with spinal stenosis.

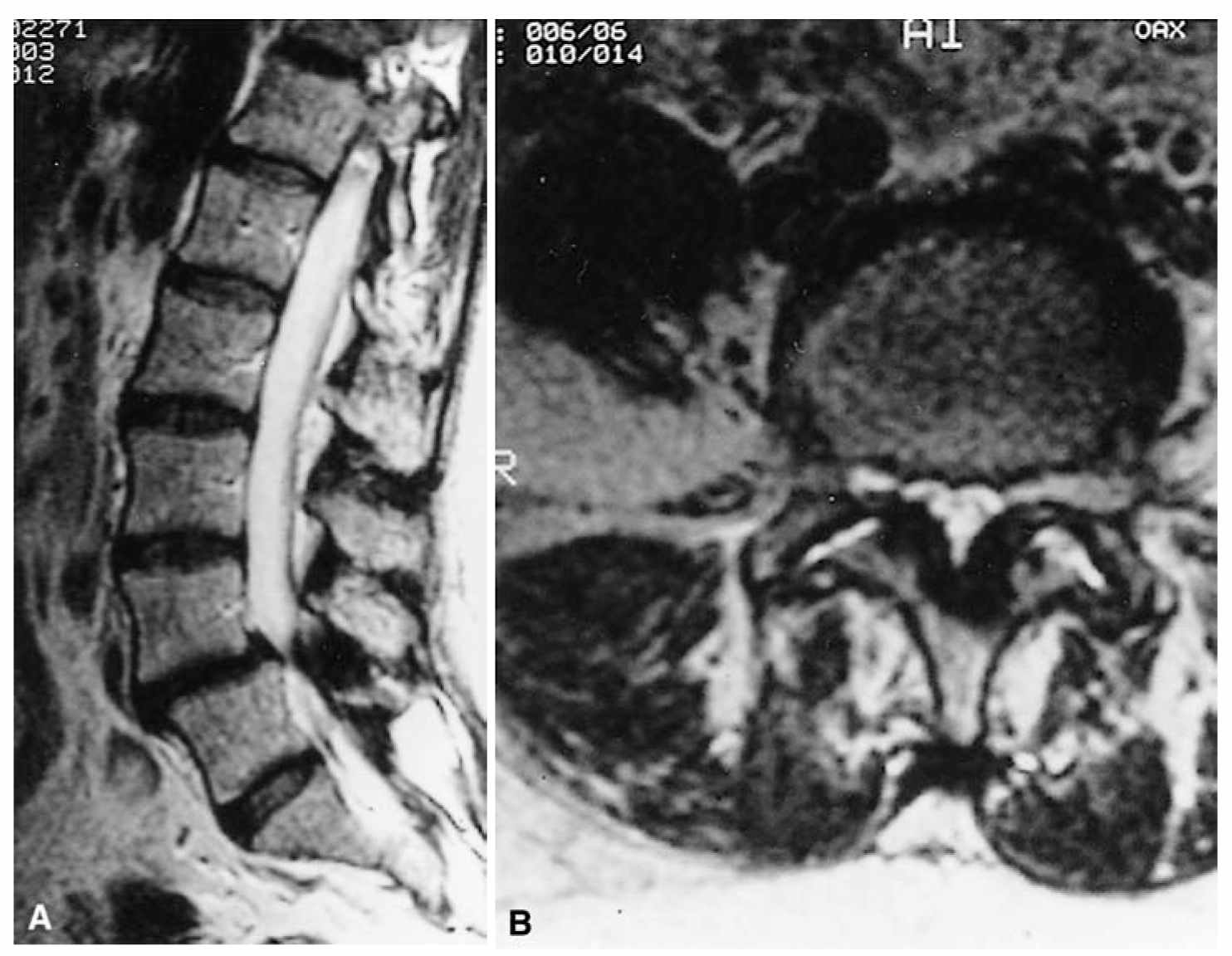

2. An MRI is the best study for evaluating the number of levels involved and the severity of the spinal stenosis. Figure 23.3 is an MRI that shows severe stenosis at L4–L5.

3. CT can be used if MRI is not available, but CT does not show the complete lumbar spine and has poorer resolution.

4. A bone scan should be obtained if there is a history of malignant disease.

5. Radiographs of the hip are needed if there is decreased range of motion of the hip or pain with rotation of the hip.

6. Laboratory tests. CBC and differential and ESR should be obtained and possibly serum and urine protein electrophoresis performed if there are systemic symptoms. A prostatic specific antigen assay should be performed for male patients older than 50 years.

7. Arterial Doppler ultrasonography should be performed if the patient has diminished or absent peripheral pulses.

FIGURE 23.1 A: T1-weighted sagittal MRI shows a lumbar disc extrusion at L5–S1 that has gone down the lumbosacral canal (arrow). B: T2-weighted axial MRI shows a large, extruded L5–S1 disc fragment (solid arrow) compressing the right S1 nerve root (open arrow).

FIGURE 23.2 Lateral plain radiograph of the lumbosacral spine shows spondylolisthesis of L4 on L5.

TREATMENT

A. Acute low back pain. Approximately 90% of patients with acute low back pain recover within 1 month. Treatment is as follows:

1. Restriction of patient activities as tolerated.

2. Acetaminophen.

3. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

FIGURE 23.3 A: T2-weighted sagittal MRI shows segmental stenosis at L4–L5. B: Axial T2-weighted MRI shows severe stenosis at L4–L5. There is marked facet and ligamentous hypertrophy.

4. Opioids, but for no longer than 2 weeks.

5. Short course of steroids (3 to 5 days).

6. Muscle relaxants.

7. Heat.

8. Epidural and/or facet steroid/lidocaine injections.

9. Limit lifting to 20 lb (9 kg) for moderate to severe back pain. Activity restrictions at work should seldom be extended beyond 3 months.

10. Surgery may be considered if the back pain is associated with a more serious problem (Table 23.1). Rarely surgery is done for refractory back pain that is associated with a degenerative disc, a positive discogram of the level of the degenerative disc, and no response to conservative therapy.

B. Lumbar disc disease with sciatica. The initial management of sciatica is similar to that of acute low back pain. At least one half of patients with sciatica improve within 1 month.

1. Two to four days of rest with gradual return to normal activities.

2. Acetaminophen.

3. NSAIDs.

4. Short course of opioids (no more than 2 weeks).

5. Short course of steroids (3 to 5 days).

6. Muscle relaxants.

7. Heat.

8. Epidural steroid injections are of limited value in patients with extruded discs.

9. Limit lifting to 20 lb (9 kg). Try to keep work-related activity restrictions to no more than 3 months.

10. Surgery for lumbar disc disease should be considered for patients with severe pain that do not respond to conservative therapy, patients with significant weakness such as a foot drop, and a patient with bladder or bowel dysfunction. Surgery should be considered in a more urgent basis if there is significant cauda equina compression. Conservative therapy can be tried for a longer period of time when you are dealing with primarily nerve-root compression.

There has been an increased interest using minimally invasive techniques when surgical intervention is required. Some surgeons have made use of a tubular retractor system when performing microdiscectomies.

C. Lumbar spinal stenosis.

1. Conservative therapy requires that patients be taught to live within the limits of their walking and standing tolerances. They need to realize that they should get off their feet, if possible, when symptoms occur.

2. Patient with severe limitation of walking may benefit from the use of license plates for persons with disabilities.

3. Patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis may benefit from lumbosacral support.

4. Core strengthening experiences.

5. Epidural steroid injections have limited use.

6. Surgical treatment should be considered only if the patient’s condition is medically stable and the patient can no longer live with his or her degree of spinal claudication. Patients with true sciatica that does not respond to conservative therapy also can be considered for surgery. Surgical procedures that can be considered include lumbar laminectomy, lateral recess decompression, and spinal fusion. Seldom is surgery for spinal stenosis necessary in the first 3 months of symptoms. In most cases, the patient has symptoms for 12 to 18 months. Minimally invasive techniques are now also available for both lumbar decompression and lumbar fusion procedures.

SURGICAL REFERRAL

A. Severe and disabling sciatica.

B. Neurologic deficits such as foot drop or bladder and bowel disturbance.

C. Poor response to at least 4 weeks of conservative therapy.

D. Other red flags (Table 23.1).

Key Points

• Low back pain is extremely common and in 90% of cases will respond to conservative therapy within a month.

• Patients with back and leg pain (sciatica) most likely have nerve-root compression secondary to a ruptured lumbar disc.

• Patients older than 50 with back and leg discomfort and/or numbness and/or heaviness with standing and walking may have lumbar stenosis.

• Diagnostic workup may include plain L–S x-rays with flexion and extension lateral views and L–S MRI if the patient remains symptomatic after an appropriate trial of conservative therapy.

• Microlumbar discectomy for ruptured discs, lumbar laminectomy for spinal stenosis, and lumbar laminectomy and spinal fusion for patients with both spinal stenosis and spondylolisthesis may be needed in patients who do not respond to conservative therapy and/or have associated severe neurologic deficits.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree