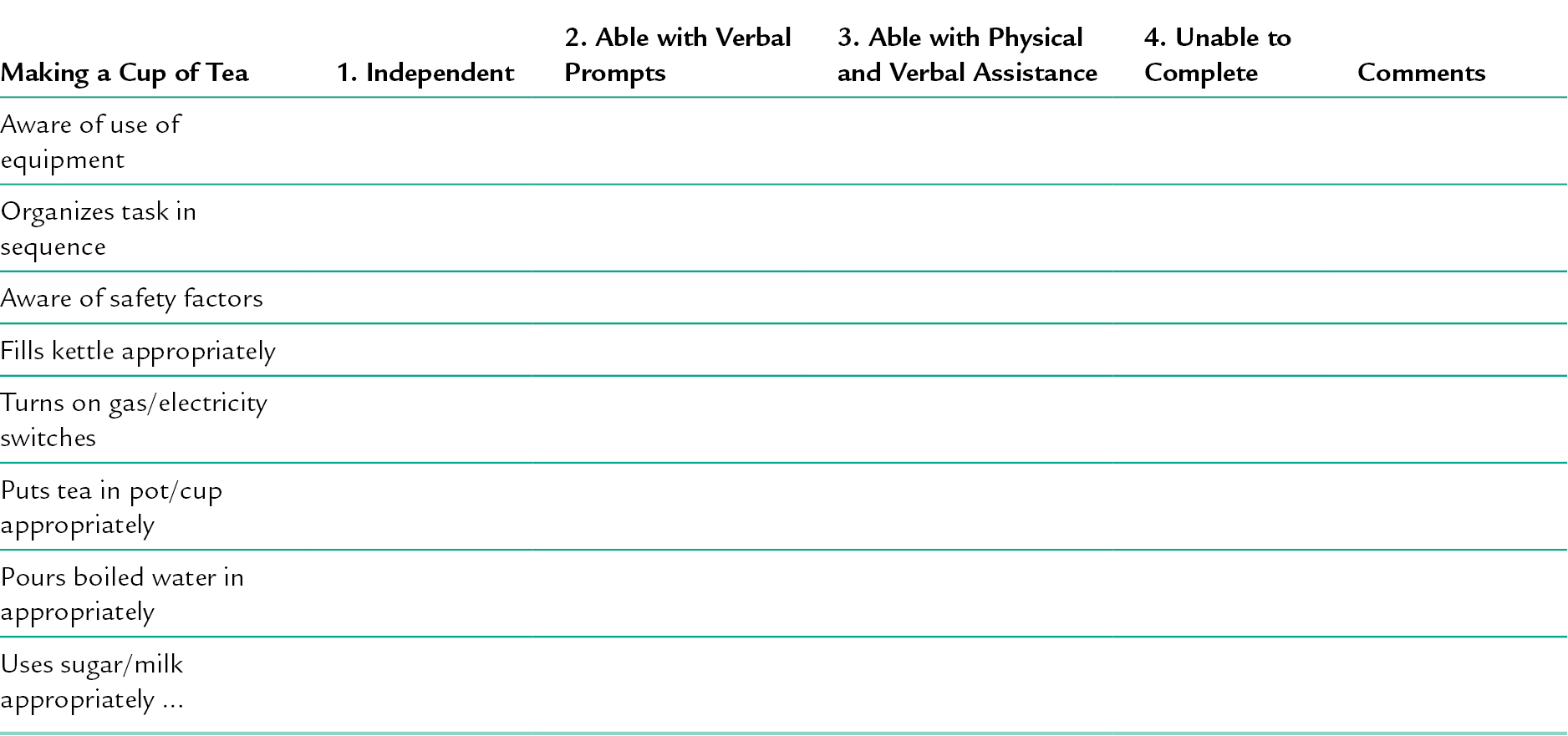

19 CHAPTER CONTENTS LIFE SKILLS, ROLES AND BELONGING Non-Standardized Assessment Tools Assessing Activities of Daily Living Assessing Instrumental Activities of Daily Living INTERVENTIONS FOR DEVELOPING LIFE SKILLS BASIC REQUIREMENTS FOR LIFE SKILLS INTERVENTIONS OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY APPROACHES The Effectiveness of Life Skills Programmes SERVICE USERS’ PERSPECTIVES ON LIFE SKILLS Occupational therapists work with individuals with mental health problems to facilitate their recovery (see Ch. 2). For any occupational engagement and participation, biological health and physical safety needs must be met (Matuska and Christiansen 2008). For example, the ability to identify appropriate foods, locate, purchase, prepare, cook and eat, underpins fundamental life skills, without which other participation potentially would not occur. Recovery involves managing the practical and social aspects of life, such as shopping, eating meals with friends or paying bills. These aspects of life are called life skills, which are associated with building and maintaining relationships with others. This makes for a complex array of skills required for recovery and for functioning effectively in life, which can be developed through occupational engagement and for which occupational therapists have a clear role (Kelly et al. 2010). In this chapter, the place of life skills in occupational therapy is explored by defining and describing life skills; considering ways to assess; and examining the interventions for developing life skills. Throughout, discussion of key issues draws on theory, practice and current evidence underpinning the approaches used by occupational therapists. The term life skills has been used to broadly describe a range of tasks and activities that support occupational and role performance. Life skills have been defined by Mairs and Bradshaw (2004) as ‘the skills required to fulfil the roles required of individuals in the setting in which they choose to reside’ (p. 217). In a Cochrane review, Tungpunkom and Nicol (2009) described life skills as managing money, organizing and running a home, domestic skills, personal self-care and interpersonal skills. A later update of this review also included therapeutic recreation (Tungpunkom et al. 2012). Life skills have been classified as self-maintenance (Reed and Sanderson 1999), which includes personal and domestic activities of daily living (Hagedorn 2001). Also they can be labelled as instrumental/activities of daily living (I/ADL) (American Occupational Therapy Association, AOTA 2008). This broad-based view of what can account for life skills is problematic. Indeed Reed’s (2005) historical review of the concepts of self-maintenance and self-care highlighted the diversity and lack of consistency. In some instances, categories in their own right being sub-categories in other literature. Before settling on a definition of life skills for this chapter, it is important to consider the place that life skills have within occupational engagement and participation as a whole. Life skills are one aspect of occupational therapy, relating to the occupations of individuals and the communities they belong to and live with. The performance of life skills may well involve doing tasks and activities that one may enjoy or one has an obligation to do (Wilcock 1998, 2006). This performance of life skills is accompanied by an implicit sense of purpose and meaning (Creek 2003, Jonsson 2008). Life skills form blocks of performance that are part of a set of tasks performed in sequences that make up activities supporting occupation (Creek 2003). Life skills are also required to perform occupational roles for which occupational engagement is integral. A given role has an internalized social and personal outlook, attitudes and specific actions. These are expressed in associated and expected behaviours and relationships to others (Kielhofner 2008). However, Creek (2010) also makes explicit the relationship to performing occupations within a role. A role example is being a mother, who has her views on parenting and understands expected behaviours (Creek 2010) associated with the IADL of child-rearing (AOTA 2008). Having a work role or even just functioning in life today would require the IADL of communication management (AOTA 2008). This may require the use of technology. It is important to note that the same or similar life skills could be required for a number of different roles in ADL, such as dressing and meeting personal hygiene and grooming needs (AOTA 2008). A combination of life skills therefore helps to meet role needs and expectations. Roles and the life skills required to fulfil them are also linked to social activities and relationships, where the psychological and emotional needs for belonging and support are met (Rebeiro et al. 2001). Communication and interaction skills are not discussed in this chapter, but they are often required as a part of other life skills, such as shopping when speaking to shop assistants. Life skills and roles also relate to cultural, spiritual and religious aspects of occupation discussed later in the chapter. Meeting occupational needs is believed to have an effect on health and wellbeing (Doble and Santha 2008) and may, in part, be addressed by life skills. For many people, maintaining life skills and roles, and gaining a sense of belonging, can be a daunting prospect. A person may have to manage many aspects of their mental health problem and the reaction of others, as well as the impact on their own participation. This can mean being stigmatized by the wider community and feeling alienated as a result (Townsend and Wilcock 2004). The challenge in managing these different elements of life can make it difficult to develop effective and socially valued roles which increase the sense of belonging (Wilcock 2006). In the mental health setting, addressing life skills means helping people to manage a range of occupations within the category of self-maintenance. This category is related to and may influence effective engagement in productivity and leisure. This focus forms part of the broader aim of occupational therapy to enable people to participate in occupations and associated roles. These categories are regularly used by occupational therapists (Jonsson 2008; see also Chs. 18 and 21). Categorizing occupations is important, not only to distinguish them but also to understand how they relate to each other. Individuals categorize occupations differently, depending on how the occupations are perceived in relation to personal interests, needs and meanings (AOTA 2008). Implicit within the categories of occupation are two concepts: occupational engagement and participation. Each concept denotes slightly different aspects and they are defined here. Engagement is ‘a sense of involvement, choice, positive meaning and commitment while performing an occupation or activity’ (Creek 2010, p. 166). This sense of involvement is linked to the internal emotional and psychological world of the individual and is experienced when performing an activity or occupation (Creek 2010). Participation is ‘involvement in life situations through activity within a social context’ (Creek 2010, p. 180). In this definition, the emphasis is placed on doing as influenced by, and performed within, the norms and expectations in a given culture and social milieu (Creek 2010), of which roles form a part. This demonstrates the complexity and multidimensionality of each occupation for each individual (AOTA 2008) within a social context. Addressing life skills in the mental health setting means helping service users to manage a range of occupations within the category of self-maintenance that also are related to, and may influence, effective engagement in productivity and leisure. All form part of the broader role of the occupational therapist to enable service users to participate in occupations, associated roles and develop a balance in occupational engagement and participation (Wilcock 1998). It is clear that the term ‘life-skill’ has no one definition. For the purposes of this chapter, life skills will be regarded as activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) as AOTA (2008) defines, i.e. ■ Activities of daily living are basic or personal and are ‘fundamental to living in a social world; they enable basic survival and wellbeing’ (AOTA 2008, p. 631) ■ Instrumental activities of daily living are ‘activities to support daily life within the home and community that often require more complex interactions than self-care used in ADL’ (AOTA 2008, p. 631). They are complex multistep activities requiring the integration of higher-level cognitive skills (McCreedy and Heisler 2004). Table 19-1 summarizes these activities. The ways in which life skills problems can manifest are discussed next. TABLE 19-1 A Summary of the Activities Categorized as Activities of Daily Living and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living People may have a variety of life skills problems. The occupational therapist needs to build a picture of the individual’s constraints and strengths, considering how occupational limitations are related to the signs and symptoms of the person’s mental health problems. Undertaking an activity analysis is important to help understand in what aspects of the particular life skill the individual has problems with. This is used as a basis for discussion when intervention planning (see Ch. 6). This section uses the example of schizophrenia and the associated difficulties identified in the occupational therapy and psychology literature. (The signs and symptoms of schizophrenia are not specified here, and the reader is directed to familiarize themselves with a psychiatric textbook for details). Schizophrenia has been found to affect the balance of an individual’s occupations; it can result in engagement in passive activities and a low level of daily structure (Bejerholm and Eklund 2004). Under-activity may lead to a sedentary lifestyle (Bejerholm 2010a). This can lead to limited experiences of accomplishment (Bejerholm 2010b) and may affect the ability and wish to initiate life skills. It must not be assumed that all of these problems will be apparent for every person with schizophrenia. It is also important to note that some life skills may not be considered by some to be meaningful occupations. A person-centred approach (Sumsion, 1999) is therefore required to understand the individual’s perspective of their occupational capacity and their sense of meaning in performing life skills. This has to be balanced with the possibility of vulnerabilities such as self-neglect and its impact on health and wellbeing. When valued life skills are identified and risks are known, the occupational therapist may decide to use specific assessments (see below). People can experience limited societal acceptance due to stigma, impacting on their sense of belonging within a community (Andonian 2010). This can lead to barriers in participation (Yilmaz et al. 2008) and therefore difficulties maintaining and developing roles. The attitudes of others can limit opportunities to develop friendships. A lack of a close and reliable friend has been found to limit occupational engagement (Bejerholm 2010b). However, an acute phase can impact on this. At this time, the need to make new friends may be less of a priority (Bejerholm 2010a). The physical environment and the location of occupations can also impact on social connections and participation (Yilmaz et al. 2008). There are cognitive difficulties with real-world daily life task functioning (Rempfer et al. 2003) for people with schizophrenia. Learning and memory can be affected (Green et al. 2000). Executive function problems impact on initiating and performing tasks and solving new or conflicting problems in complex or unfamiliar situations (Green et al. 2000). Awareness (insight) problems, such as lack of knowledge or recognition of deficits, lead to lack of initiation of activities and limited success in rehabilitation (Katz and Hartman-Maeir 2005). This may lead to a withdrawal from performing life skills, which may lead to boredom (Bejerholm 2010b), stagnation and emptiness permeating occupational patterns and time use (Bejerholm and Eklund 2004). This can also lead to an impaired sense of meaning of the activity for the person, which limits participation (Yilmaz et al. 2008). Participation and engagement happen within an environment with social and community aspects, as well as physical (architectural and natural) space (Baum and Christiansen 2005; Kielhofner 2008). The sociocultural and religious aspects of life skills that form a part of participation need to be explored by the occupational therapist. This section can only briefly introduce the huge diverse range of cultural and religious differences in occupational performance. Cultural beliefs influence occupational patterns, choice of activity level, perceptions of value of occupations influencing engagement in them (Chiang and Carlson 2003; Bonder et al. 2004). The occupational therapist has to consider cultural values in relation to what people do. For example, Fair and Barnitt (1999) explored a range of different ways in which a cup of tea was made by 15 students and colleagues from South Asia, Africa, Europe and Australia. The ways of making tea, the meaning of doing this and the purpose for doing it varied between and within cultures and across generations. This suggests that occupational therapists need to be open to reviewing their existing and traditional practices of using hot drinks for assessment when working with people from different cultures (Fair and Barnitt 1999; see also Table 19-2). In research about service users’ perspectives of their experience of mental health inpatient rehabilitation, some participants felt the focus on independence and life skills was not necessarily culturally relevant (Notley et al. 2012). Gibbs and Barnitt (1999) explored four aspects of self care (dress, diet, bathing and toileting) in a study involving 19 Hindu elders. The concept of independence was not understood by the participants, who valued and expected family members to care for them. As elders, they were central to and supported by an extended social group. Sensitivity must be shown to these situations and expectations in assessment and intervention planning. Religious observance is an IADL (AOTA 2008). Participants in a black and ethnic minority focus group identified that the consideration of spiritual and religious needs may be a focus for occupational therapists. Returning to the community could involve church and faith groups: understanding and exploring how people wish to express their spirituality may be very important (College of Occupational Therapists 2006). These examples provide a sense of cultural and religious aspects that need to be considered in relation to life skills. Therapists also need to be aware of their own cultural beliefs and behaviours and how that impacts upon their understanding and sensitivity to others from a different background (Chiang and Carlson 2003). Even within a single society, people have different backgrounds and therefore attach different meanings to the occupations they value (Darnell 2009). Culture also has an emergent nature and the therapist must recognize whatever cultural issues are established, they need to be seen as a means of generating preliminary hypotheses to be tested for the specific person (Bonder et al. 2004). This leads into a consideration of how to assess life skills. Assessment of life skills for mental health service users should be holistic and starts with observation (see Ch. 5). The therapist must have completed an activity analysis of the life skill to guide assessment of the person’s strengths and constraints. This analysis includes psychological/emotional, social, cognitive, sensory and physical aspects of performing life skills, as well as the environment in which these will be performed. It may also be useful to know the educational background and level of achievement in other areas of occupation. Beyond this point, decisions can be made about what form of assessment would be required. However, it is also important to know for what purpose the assessment is required. For instance, the life skill needs of a person returning to live alone are different to one going to live in a group home. In the mental health setting, relevant initial observations can indicate problems an individual may be experiencing in relation to life skills areas and include the following: ■ Mood and affect: Levels of anxiety and discomfort ■ Appearance: The state of clothing and whether dressed appropriately for weather conditions, malodorous smells, body weight, and application of make-up and hair and nail condition ■ Cognition: Attention and concentration during discussion prior to, and during, observations of I/ADL. The assessment can take the form of a checklist of aspects of the activity that would be required to perform it effectively. For example, the checklist might focus on making a cup of tea (see Table 19-2). Here, a person would be observed and a tick placed at the appropriate score and descriptor box; making additional comments as required. This may also be constructed for a different activity, such as making a sandwich, or occupations such as shopping for groceries. Whatever assessment is used, it is important to give the person the fullest opportunity to complete all or as much of the assessment as they can before the occupational therapist intervenes. As soon as the occupational therapist alters the way an assessment is performed, the clearest picture of strengths and constraints for the person is altered. The therapist must not alter the progress unless the possibility of harm arises and the person appears unable to deal with this possibility. For example a pan has some oil that is over-heating, producing a lot of smoke and could catch alight. Should the therapist need to intervene, this should be recorded as part of the assessment. It may be that the person lost concentration, lacked knowledge or was distracted in some way. These may indicate the impact of their mental health problem on their occupational functioning. However, it is also important to get feedback from the person about their perspective of what happened. Tools to measure life skills may be linked to a specific model of practice, or they may stand alone, but there should always be a theoretical basis underpinning the assessment. The following section therefore considers some new developments with stand-alone assessments. A sensitive approach is required for assessment by discussion or observation of personal activities, such as bathing, showering, bladder and bowel management, and personal hygiene and grooming (see Case study 19-1 for an example from practice). The initial observations of mood and appearance can be helpful in assessing some aspects of these activities. All attempts to prevent or minimize the person’s embarrassment should be made. Discussion may be better than a full observational assessment. However, if the person is unable to fully verbalize their abilities in these areas, asking someone who regularly assists with these activities, with the person’s consent, can help the therapist to understand the needs. Ultimately, observation may be the only way to assess fully the specific difficulties.

Life Skills

INTRODUCTION

WHAT ARE LIFE SKILLS?

LIFE SKILLS, ROLES AND BELONGING

Categorizing Life Skills

Activities of Daily Living

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

Bathing and showering

Bowel and bladder management

Dressing

Eating

Feeding

Functional mobility

Personal device care

Personal hygiene and grooming

Sexual activity

Toilet hygiene

Care of others (including selecting and supervising care-givers)

Care of pets

Child-rearing

Communication management

Community mobility

Financial management

Health management and maintenance

Home establishment and management

Meal preparation and clean up

Religious observance

Safety and emergency maintenance

Shopping

Individual Needs

Culture and Religion

ASSESSING LIFE SKILLS

Non-Standardized Assessment Tools

Assessing Activities of Daily Living

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree