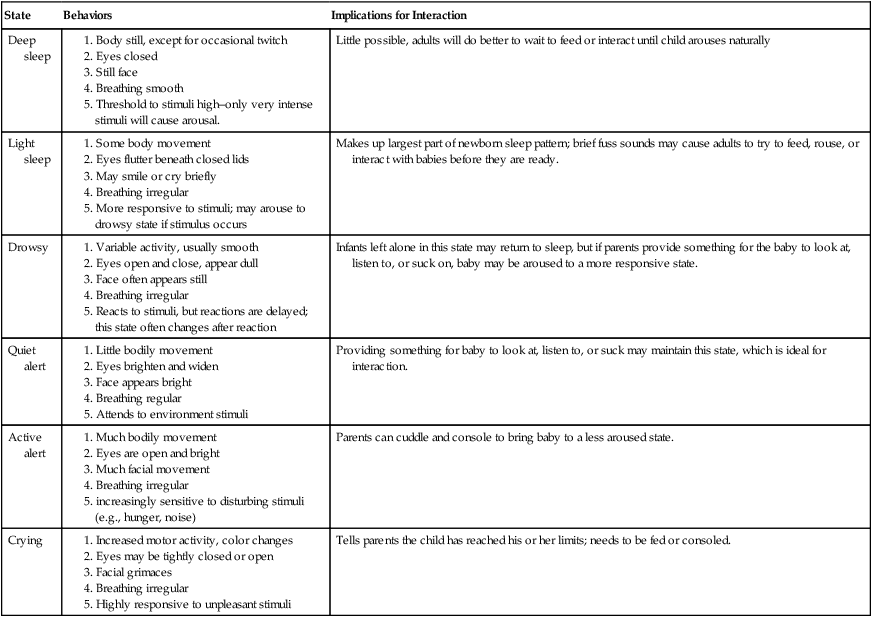

Chapter 6 Readers of this chapter will be able to do the following: 1. Discuss the principles of family-centered practice for infants and newborns. 2. Describe the elements required for service plans for prelinguistic clients. 3. List risk factors for communication disorders in infants. 4. Discuss the principles of assessment and intervention for high-risk infants and their families in the newborn intensive care nursery. 5. Describe methods for assessment and intervention for preintentional infants and their families: 1 to 8 months. 6. Describe assessment and intervention for infants at prelinguistic stages of communication: 9 to 18 months. 7. Discuss the issues relevant to communication programming for older prelinguistic clients. 8. Describe assessment and intervention strategies for prelinguistic children with autism spectrum disorders. Janice is one kind of baby who is at risk for language and communication disorders. There are many kinds of risk (see Paul & Roth, 2011); what they have in common is their impact, not only on the infant but also on the family. The burden of caring for and fostering the development of infants at risk for communication disorders falls on their families, who may already be experiencing a great deal of stress. Even caring for a healthy newborn is hard work. Imagine how much harder that work becomes when it is done in the context of constant anxiety about the infant’s well-being and future. When we deal with infants at risk for communication disorders we are dealing with the family in which the infant finds a home. Although this is true for every client we see, it is especially true for the very youngest of our charges, who depend on the adults in their environment for every aspect of their existence. When thinking about the needs of the high-risk infant, we need to think about the needs of the family, too, to provide that infant with the best environment for growth and development. A variety of resources are available to help clinicians develop family-centered practice skills. Bruns and Steeples (2001) and Crais (1991), for example, made some suggestions for strategies to be used in family-centered practice. These strategies are summarized in Appendix 6-1. Additional resources include Andrews and Andrews (1990), Crais and Calculator (1998), Dinnebeil and Hale (2003), Donahue-Kilburg (1992), Griffin (2006), and McWilliams (1992). 1. Information about the child’s present level of physical, cognitive, social, emotional, communicative, and adaptive development, based on objective criteria. 2. A statement of the family’s resources, priorities, and concerns related to enhancing the development of the child, with the concurrence of the family. 3. A statement of the major outcomes expected to be achieved for the child and family, and the criteria, procedures, and timelines used to determine progress and whether modifications or revisions of the outcomes or services are necessary. 4. A statement of the specific early intervention services necessary to meet the needs of the child and the family to achieve the specified outcomes including (1) the frequency, intensity, and method of delivering the services and (2) the environments in which early intervention services will be provided and a justification of the extent, if any, to which the services will not be provided in a natural environment, the location of the services, and the payment arrangements, if any. 5. A list of other services such as (1) medical and other services that the child needs and (2) the funding sources to be used in paying for those services or the steps that will be taken to secure those services through public or private sources. 6. Projected dates for initiation of the services as soon as possible after the IFSP meeting and anticipated duration of those services. 7. The name and discipline of the service coordinator who will be responsible for the implementation of the IFSP and coordination with other agencies and persons. Johnson, McGonigel, and Kaufmann (1989); Nelson and Hyter (2001); and Yaoying (2008) provided guidelines for developing IFSPs. They reported that no official form or format has been approved for these plans in order to give teams the freedom to develop whatever works best for an individual family. Some teams use only handwritten IFSPs to allow for immediate recording and to keep them dynamic and easy to revise. Other teams create model formats that can be adapted to individual families by the team members. Some teams now use hand-held or tablet electronic devices, such as the iPhone or iPad to create IFSPs from templates the team designs (e.g., Thao & Wu, 2006; Wu et al., 2007). An example of one possible format for an IFSP appears in Appendix 6-2. Other children in the prelinguistic stage of development may be identified some time after birth. Some will be discovered through Child Find and other screening programs. Child Find programs are mandated by the IDEA and are targeted at early identification of children with special needs who might not otherwise come to the attention of agencies who could serve them. These children may have conditions that are not identified at birth, nonspecific forms of intellectual disability that have no obvious physical signs, or autism that does not become apparent until later when communication skills emerge in normal development. As Nelson (1998) pointed out, finding these children is not as easy as it sounds; even many professionals are unaware of the need for and appropriateness of intervention in this very early part of life. Public education of both parents and professionals is an important component of Child Find efforts, in order to increase the likelihood that children will be referred for diagnostic services. Multiple observations are often needed to establish special needs in early development, since infant behavior changes so dramatically during the first year of life. Many of the instruments used for screening and diagnostic assessment in the prelinguistic period are listed in Appendix 6-3. Using instruments with strong psychometric properties is just as important in early assessment as it is for any client, for all the reasons we talked about in Chapter 2. Clinicians choosing assessment instruments for prelinguistic children should apply all the same psychometric standards in making this judgment that would be used in selecting tests for older children. Similarly, we will always need to supplement standardized instruments with more flexible and ecologically valid measures. Crais (1995, 2011) and the American Speech-Language and Hearing Association (ASHA, 2008) discussed the importance of including caregivers as significant partners in the assessment, and using culturally sensitive procedures and naturalistic observations of play and other daily routines within the assessment process. These measures, which go beyond traditional instruments, will always contribute important information to the data that we collect. When providing services to high-risk infants and their families, the language pathologist will be an integral part of the team of professionals developing the IFSP. Language disorders are the most common developmental problem that presents in the preschool period (ASHA, 2008), so any infant at risk for a developmental disorder in general is at risk for language deficits in particular. These babies do not have communication disorders yet; work with high-risk infants and their families is a preventive form of intervention. We’ve talked about primary and secondary prevention as important aspects of the role of the speech-language pathologist (SLP). When working with high-risk infants, primary and secondary prevention are the predominant goals. We hope that by working with these families to enhance the baby’s communicative environment, we can ward off some of the deficits for which they may be at risk or minimize the extent of these deficits. Who are high-risk infants? Any condition that places a child’s general development in jeopardy also constitutes a risk for language development. The March of Dimes (2003) estimates that 12% of newborns can be considered as high risk. In this chapter, we’ll discuss some of the conditions that place an infant at risk and talk about strategies for serving at-risk infants and their families at three different developmental stages: the newborn period, the preintentional period from a developmental level of 1 to 8 months, and the period of prelinguistic communication from a developmental age of 9 to 18 months. First, let’s look at some of the conditions that place an infant at risk for communication disorders. Prematurity is defined as birth prior to 37 weeks’ gestation, with low birth weight. Low birth weight is defined as less than 2500 grams, or 5.5 pounds; very low birth weight (VLBW) is considered less than 1500 grams, or 3.3 pounds. Seriously premature birth and its consequent low birth weight can constitute both medical and developmental risks; low birth weights have been found to be associated with increased risk of developmental delay (Fanaroff, Hack, & Walsh, 2003; Gargus et al., 2009; Taylor, Burack, Holding, Lekine, & Hack, 2002). Premature infants are also more susceptible to a range of illnesses and conditions that produce developmental disabilities, such as respiratory distress syndrome, apnea (interrupted breathing), bradycardia (low heart rate), necrotizing enterocolitis (a serious intestinal disorder), and intracranial hemorrhage (Bernbaum & Batshaw, 2007). Respiratory distress in premature babies can sometimes lead to the need for intubation and the use of ventilators to aid breathing, as it did in Janice’s case. This can, in a minority of instances, lead to bronchopulmonary dysplasia, a thickening of the immature lung wall that makes oxygen exchange difficult (Rais-Bahrami, Short, & Batshaw, 2002). For children suffering from this condition, long-term tracheostomy may be necessary, which can affect both speech and language development (Mathew, Worth, & Mhanna, 2010; McGowan, Bleile, Fus, & Barnas, 1993; Woodnorth, 2004). Furthermore, treatment of the premature child may have negative consequences, even though it is necessary to save the child’s life. Newborn intensive care nurseries can be noisy and overstimulating (Aucott, Donohue, Atkins, & Allen, 2002); in the past, some infants even suffered noise-induced hearing losses (Kellman, 2002). The communicative environment also presents risks. Infants there undergo painful procedures such as suctioning and intubation, which can cause oral defensiveness or aversion, and trauma or tissue damage to the larynx (Comrie & Helm, 1997). Parents are unable to spend as much time interacting with very small newborns as parents of larger babies, because of the infants’ need for hospitalization and medical treatment. Furthermore, the parents’ perception of the baby as weak and sick may result in less willingness to hold, handle, and play with the child. The first hurdle that the premature infant faces is to survive the premature birth. The smaller and younger the baby is at birth, the greater the chances for mortality. Survival rates for very small (500 to 1500 grams) or very young (more than 10 weeks’ preterm) babies are increasing, though, because of advances in intensive care for newborns. As recently as 1960, only about 50% of these babies survived, whereas by 2002 survival rates were 55% for infants weighing 501 to 750 grams, 88% for 751 to 1000, 94% for 1001 to 1250, and 96% for 1251 to 1500 (Fanaroff et al., 2007). As more of these tiny babies—who would not have lived 50 years ago—mature, the rate of developmental delays seen in the population of children with a history of prematurity also may increase. Current estimates place the risk of developmental delays near 50% for all infants born prematurely (Rosetti, 2001; Woodward et al., 2006), and, on average, full-term infants have significantly higher cognitive scores compared with children who were born preterm (Bhutta, Cleves, Casey, Cradock, & Anand, 2002). The good news is that early intervention clearly makes a difference. Blair and Ramey (1997); Bleile and Miller (1993); and Rauh, Achenbach, Nurcombe, Howell, and Teti (1988) reported that low-birth-weight babies who receive intervention consistently show benefits over untreated groups in terms of IQ. Spittle et al. (2007) reported that preterm infants treated after discharge did better than untreated peers through preschool age, although longer term follow-up suggests that children with birth weights above 2000 grams derive the most long-term benefit from early intervention (McCormick et al., 2006). Ment et al. (2003) showed that early intervention had its greatest effect on infants whose mothers had less than a high school education. These findings suggest that a relatively small investment in intervention can have important effects for children who have risks associated with prematurity and low birth weight. Many congenital and inherited disorders also place children at risk for developing language and cognitive deficits. Inborn errors of metabolism, such as Hurler syndrome, Hunter’s syndrome, and Morquio syndrome, are examples. Craniofacial disorders, which have adverse effects on the morphology of the auditory mechanism, as well as congenital forms of deafness, put a child at risk because information from the auditory channel is lost. A variety of chromosome abnormalities also can influence communicative development. These include DS (trisomy 21; three members of chromosome 21, instead of the normal two) and Cri du Chat syndrome (5p-, absence of the short arm of the fifth chromosome). Disorders of the sex (X and Y) chromosomes present with fewer physical stigmata than other genetic disorders. As a result, they are often undetected during infancy and may only be diagnosed later, when the child starts to exhibit delays. Sex chromosome disorders include Klinefelter’s syndrome (usually an XXY chromosome complement in males, instead of the usual XY), Turner’s syndrome (X0 in females, instead of the usual XX), and fragile X syndrome. Batshaw et al. (2007) provide a detailed discussion of chromosomes and hereditary disorders. Each year approximately 12% of infants begin life in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) (ASHA, 2004a; Bruns & Steeples, 2001). ASHA has recently outlined the roles that SLPs can play in the NICU (ASHA, 2004a). Some SLPs spend most of their workday assisting families in the NICU; other hospital-based SLPs may be called in to consult on the management plan of an infant being cared for in the NICU in order to provide assessment and intervention in several areas. We’ll take a brief look at the basic areas to consider for prelinguistic infants: feeding and oral motor development, hearing conservation and aural habilitation, infant behavior and development, and parent-child communication, with reference to NICU infants in the next few sections. It is important to know, though, that practice in the NICU is a highly specialized area and most hospitals require extensive training or demonstration of specific competencies of SLPs who work in this setting. Infants in the NICU frequently have complex medication issues and very often therapy goals are secondary to keeping the infant physiologically stable. The following sections will serve only as an introduction to this broad topic. Gardner et al. (2010) provide a more in-depth discussion. The ability to take nutrition orally is one of the criteria for discharging infants from the NICU (McGrath & Braescu, 2004). As such, promoting oral feeding is an important aspect of helping prepare the child and family for life at home. Evaluating feeding and oral motor development in the high-risk newborn involves two components: chart review and bedside feeding evaluation. Alper and Manno (1996) suggest that chart review should yield information on adjusted gestational age, excess amniotic fluid at delivery that could signal a lack of intrauterine sucking and swallowing, type and duration of intubation, respiratory disorders, and degree of family involvement. Bedside feeding evaluation can be used to observe the infant’s behavior and state during feeding, the effects of environmental stimuli on the infant’s feeding behavior, vocalizations and airway noises during feeding, and reflex patterns. According to Jaffe (1989), reflexes that should be observed in the infant during feeding include the following: 1. Suckling: a primitive form of sucking that includes extension and retraction of the tongue as well as up-and-down jaw movements and loose closure of the lips. 2. Sucking: a more mature pattern, which differs from suckling in that more intraoral negative pressure is generated, the tongue tip is elevated rather than extended and retracted, lip approximation is firmer, and jaw movement is more rhythmic. 3. Rooting: causes the infant to turn the head toward the source of tactile stimulation (gentle rubbing) of the lips or lower cheek. 4. Phasic bite reflex: When teeth or gums are stimulated, usually by placement of the bottle or nipple in the mouth, the baby exhibits a rhythmic bite-and-release pattern that can be observed as a series of small jaw openings and closings. McGrath and Braescu (2004) and Ziev (1999) provide guidelines for determining whether a baby is developmentally ready to begin nipple feeding. Using a developmental evaluation, such as Brazelton and Nugent’s (1995) Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale or Lester and Tronick’s (2004) NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale, we can estimate developmental level and determine whether the premature infant has developed sufficiently to engage in some form of nipple feeding. Additional considerations for beginning oral feeding are presented in Box 6-1. In addition to observational assessment, several formal procedures are available for collecting information on feeding and oral skills. These are outlined in Appendix 6-4. Howe et al. (2008) reviewed seven feeding assessments and found limitations in the representativeness of their samples, which, in turn, limit the soundness of their psychometric properties. They reported that Neonatal Oral-Motor Assessment Scale (Braun & Palmer, 1986) showed more consistent psychometric properties than the others, although, it, too, had limitations. They cautioned that results of any neonatal feeding assessment tool needs to be interpreted with caution, because of these limitations. Barlow et al. (2010); Jelm (1990); Kedesdy and Budd (1998); Lowman, Murphy, and Snell (1999); Morris and Klein (2000); VanDahm (2010); and Wolf and Glass (1992a) provide additional information on infant and childhood feeding disorders. If formal assessment procedures are unavailable, informal interviews also can be used to gather data about the infant’s feeding and oral skills. Box 6-2 provides some of the questions that could be asked in an informal interview. Children with disabilities or those with tracheostomies often experience gastroesophageal reflux, or the backward flow of contents of the stomach up into the esophagus. This condition can seriously interfere with nutritional intake and desire to eat by mouth (Eicher, 2002). Special diagnostic procedures, which will be described a bit later, are often undertaken by the physician when this condition is suspected. The results of the feeding and oral assessment provide the clinician with information necessary to make decisions about whether feeding therapy is needed and what aspects of the feeding and oral behavior ought to be addressed. Very often, though, because of the neurological immaturity of the infant in the NICU or because of other medical conditions contributing to intolerance of enteral feeding (by way of the intestines), which can result in excessive vomiting and lead to esophagitis and oral defensiveness, oral feeding may not be an option. In these cases, tube feeding may be initiated. The decision to tube feed is usually made by the physician, and the SLP may not be consulted. But, as Imhoff and Wigginton (1991) pointed out, the SLP can be an important advocate for the parents in understanding the tube feeding decision and its consequences, in helping them to ask appropriate questions of the medical staff, and in making the eventual transition from tube to oral feeding. To serve in this advocate role, the SLP should be familiar with the various forms of tube feeding. Infants who need nonoral feeding for extended periods, particularly if they need endotracheal tubes to help them breathe as well, may show decreased sucking and oral motor development (Barlow et al., 2010; Comrie & Helm, 1997). An important contribution that the SLP can make to this situation is to encourage parents and medical personnel to offer the baby opportunities for non-nutritive sucking (e.g., pacifier) during the tube feeding. This will help strengthen the sucking reflex and also help the baby learn to associate sucking with feeling contented from feeding. Other oral stimulation, such as stroking the cheek, lips, and gums, may also help make the child ready for oral feeding (Fucile, Gisel, & Lau, 2005). Arvedson et al. (2010) showed that non-nutritive sucking alone and combined with oral stimulation showed strong positive results for reducing transition time to oral feeding. The SLP also can take the time, which medical personnel will not always be able to do, to explain why the feeding tube is needed and to reassure the family that normal feeding will eventually be achieved. Furthermore, the SLP can encourage the family to ask about supplementary oral feedings and may encourage the parents to ask the physician about using a G-tube to minimize effects on oral development if prolonged nonoral feeding (more than 1 month) is necessary. If our assessment suggests that the baby is ready to graduate from nonoral to oral feeding, or is able to feed orally from the first, the SLP can use several techniques to help the infant succeed. Spatz (2004) discussed ways to promote breastfeeding for premature infants. These include working with nurses to help mothers maintain their milk supply by pumping and to safely store and track each mother’s milk, encouraging the mother to hold the baby skin-to-skin during nonoral feeding and to provide non-nutritive sucking experiences while holding the baby at the breast. When making the transition to breastfeeding, the SLP can help with positioning the infant, using a “football” hold to support the head and neck. Although hospitals are more likely to encourage breastfeeding for premature infants than they were only a few years ago, since breast milk contains many nutrients and antibodies that are beneficial to the baby’s health, some premature or high-risk infants may be unable to nurse, and their feeding times will be long and closely spaced, making nursing very difficult for the mother. Some mothers may still want to pump breast milk for the baby to drink from a bottle, and many NICUs provide breast pumps for this purpose. When the mother feels she wants to contribute to her infant’s well-being in this way, she should certainly be encouraged to do so. Fletcher and Ash (2005) discuss the importance of working with other professionals to support mothers who wish to breastfeed babies in the NICU. However, mothers should also be guided to understand that the infant can thrive on formula as well. Interaction is just as important, and perhaps more important to the babies’ development, than the milk they drink. In counseling the mother of a baby in NICU, the SLP will want to help her do for the baby what she can do best and to feel that she is making a contribution to the baby’s overcoming a difficult start. If the mother can nurse or express milk, fine. If a particular mother cannot or feels uncomfortable with these options, she can help her baby in many other ways. The SLP can play a crucial role in helping the mother to understand the importance of interaction and communication in the baby’s development and in making her see that these are her most crucial contributions to her child’s well-being. It is especially important to stress to these mothers that feeding time must be communicative as well as nutritional and to encourage mothers to develop interaction and communication early in the feeding process. 1. Positioning. Jaffe (1989) suggested that the premature baby be placed in a flexed position, with the chin tucked into the neck and the shoulders and arms pressed forward. This is an ideal “cuddling” position and can aid in bonding as well as feeding. Ideal positioning also can be achieved by placing the baby in a positioning device such as “Boppy” pillow, infant seat, or tumbleform seating. Hall, Circello, Reed, and Hylton (1987) advocated keeping the child’s face near the feeder’s to encourage eye contact and social interaction. Comrie and Helm (1997) provide additional detailed positioning alternatives. The mother’s comfort and the baby’s success are most important in deciding on a position for feeding. Trial and error may be necessary to find the best position. 2. Jaw stabilization. The mother can place her thumb or finger on the baby’s chin, just below the lower lip, another finger on the temporomandibular joint, and a third finger under the chin. This support allows her to stabilize the head and jaw and to provide more control as the infant sucks. This control on the mother’s part should be gradually faded as the infant’s feeding skills develop. 3. Negative resistance. Comrie and Helm (1997) suggest using negative resistance to help infants who bite rather than suck or have an inefficient sucking pattern. As the infant pulls on the nipple during sucking, the feeder tugs gently back. This often stimulates a longer and stronger suck. 4. Using specialized feeding equipment. Comrie and Helm also suggest that nipple characteristics can influence sucking patterns, and suggest that if breastfeeding is not possible, nipples with various characteristics of flow rate, suction, and compression should be tried, as well as angled bottles. Spatz (2004) advocates using a nipple shield for breastfeeding mothers, to increase baby’s milk intake. 5. Modifying temperature and consistency. Alper and Manno (1996) point out that chilling liquids has been tried to increase swallowing rate and decrease pooling of liquid in the pharynx. However, the main effect of this change may be to thicken the liquid, which may make it easier to swallow. Formulas also can be thickened by adding rice cereal. 6. Oral stimulation in feeding. McGowan and Kerwin (1993) suggested providing oral stimulation during feeding. They advised having parents use the following sequence to introduce bottle feeding: a. Stroking the nipple on the side of the baby’s cheek to elicit a rooting reflex. b. Touching the nipple to the center of the lips and gum surface to produce mouth opening. c. Allowing the baby to close on the nipple and start sucking, then stroking upward on the palate in a rhythmic motion with the nipple to encourage continued sucking. 7. Nonfeeding oral stimulation. In addition to being encouraged to touch and stroke their babies’ bodies in the NICU, mothers also should be encouraged to provide gentle stimulation to the baby’s face, rubbing it gently with fingers or soft toys and providing non-nutritive sucking of a pacifier or finger whenever possible (Fucile, Gisel, & Lau, 2005). McGowan and Kerwin (1993) gave some specific suggestions for oral stimulation activities, including the following: a. Putting a finger (nail down) in the baby’s mouth and rubbing the palate with an upward motion (midsection to front) to stimulate non-nutritive sucking. b. Rhythmically stroking the midsection of the tongue, front to back. c. Rubbing the infant’s cheeks, one at a time, with a circular motion. d. Tapping around the baby’s lips in a complete circle. e. Placing a finger or toothbrush in the mouth and massaging the upper and lower gums. Additional resources for assessing and managing infant feeding problems include Alper and Manno (1996); Arvedson and Brodsky (1993); Eicher (2002); Johnson-Martin, Hacker, and Attermeier (2004); Kedesdy and Budd (1998); Lowman, Murphy, and Snell (1999); McGrath and Braescu (2004); Morris and Klein (2000); Spatz (2004); Tuchman and Walter (1993); van Dahm (2010); and Wolf and Glass (1992a). Forty-four states mandate hearing screening for all newborns in the NICU. But, as we discussed earlier, the NICU itself may be hazardous to the baby’s health. Clark (1989) reported that the incubators, cardiorespiratory monitors, and ventilators present in the NICU can generate noise levels of more than 85 dB, which not only interferes with sleep but may result in hearing loss by means of cochlear damage. This risk to hearing is in addition to the high incidence of hearing loss associated with many of the syndromes and conditions that resulted in the child being placed in the NICU in the first place. As we saw earlier, many congenital and genetic syndromes affect the development of the auditory structures, and hearing loss is one of the most important causes of the language disorders we see in such children. The SLP can play a crucial role in conserving the hearing of the high-risk newborn by making sure that aural habilitation is part of the management plan if screening indicates hearing loss. Further, the SLP should encourage the parents to have the infant’s hearing tested by an audiologist periodically throughout the child’s early years, even if losses are not identified during the newborn period. In this way any loss that occurs can be treated at the earliest possible time. Sparks (1989) emphasized that the purpose of assessment for infants should not be to predict future behavior, but to determine the infant’s current strengths and needs. First, it is important to know as much as we can about what risks the infant faces. This knowledge can help us decide how much and what kind of intervention to propose. If the child has DS, for example, we know that the risk for future speech and language delays, as well as for middle-ear dysfunction, is high. This knowledge may lead us to argue more strongly for early communication intervention than we might in the case of a child with prematurity alone. Careful interviewing of family and medical staff, as well as medical chart review, can provide this information. The Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale (Brazelton & Nugent, 1995), The Neurological Assessment of the Preterm and Full-term Newborn Infant (Dubowitz, Dubowitz, & Mercuri, 1999), the Naturalistic Observations of the Newborn, Assessment of Preterm Infant Behavior (Als, 1985), the Assessment of Preterm Infant Behavior (APIB; Als, Lester, Tronick, & Brazelton, 1982), Developmental and Therapeutic Interventions in the NICU (Vergara & Bigsby, 2004), and the NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale (Lester & Tronick, 2005) are instruments designed to look at a range of abilities for infants 28 to 40 weeks of gestational age. They help the clinician to identify the conditions under which the baby functions best, what places stress on the baby, how much handling and stimulation the baby can tolerate, how easily the baby’s homeostasis is disrupted, what supports are useful to the baby in maintaining self-control, and how much endurance the baby has for interactive functioning. Many NICUs use these instruments routinely to evaluate patients. When this evaluation has been done by medical staff, the SLP should carefully review the results for information that will help in the planning of a communicative intervention program. If no formal instrument is routinely used, the SLP should consider administering a developmental assessment. According to Gorski (1983), the goal of intervention for the baby in the NICU is to achieve stabilization and homeostasis of physiological and behavioral states and to prevent or minimize any secondary disorders that might be associated with the child’s condition, rather than to attain milestones appropriate for full-term babies. The best way for us to achieve these goals is to become a member of the NICU team and to earn the respect of the medical staff for our in-depth knowledge of early communicative and oral-motor development. When this has been achieved, the SLP can offer suggestions that will benefit communicative development. Gorski (1983), Griffer (2000), Nugent et al. (2007), and VandenBerg (1997) advocated developmentally supportive care that uses strategies like the following: 1. Encourage careful monitoring both of noise levels and infant hearing within the NICU. 2. Develop staff awareness of the dangers of ototoxic effects of medications. 3. Foster sensitivity to laryngeal damage from endotracheal tubes (Sparks, 1984). 4. Work to alleviate sensory overstimulation because of constant bright light. 5. Suggest ways to counteract the dangers of low language and interactive stimulation that can result from infrequent handling in the NICU. 6. Encourage consideration of the oral-motor consequences of continued use of N-G and gavage tube feeding, bearing in mind the surgical risks that G-tube feeding entails. The SLP can help families and medical staff to work together to consider how these risks can be balanced. 7. Advocate for the importance of non-nutritive sucking and oral stimulation to aid in the baby’s oral-motor development. 8. Educate staff about the efficacy of early intervention (Rossetti, 2001). 9. Provide information about services offered by other disciplines (e.g., SLP, occupational therapy, physical therapy, counseling) that may be of help to families of babies in the NICU. 10. Support parents in achieving their goals for the child during the NICU stay. 11. Encourage parents to talk to, touch, and hold the baby; help with positioning. 12. Help parents recognize, understand, and interpret the infants’ signals; help time caregiving and interaction to promote the infants state regulation and allow for natural sleep-wake cycles. Information gathered from an instrument, such as the APIB, will help identify the level of interactive, motor, and organizational development that the infant in the NICU is showing. This information is crucial for deciding whether the infant is ready to take advantage of communicative interaction. Gorski, Davison, and Brazelton (1979) defined three stages of behavioral organization in high-risk newborns. The child’s state of organization determines when he or she is ready to participate in interactions. These states include the following: 1. Turning In (or physiological state). During this stage the baby is very sick and cannot really participate in reciprocal interactions. All the infant’s energies are devoted to maintaining biological stability. 2. Coming Out. The baby first becomes responsive to the environment when he or she is no longer acutely ill, can breathe adequately, and begins to gain weight. This stage usually occurs while the baby is still in the NICU, and this is the time when he or she can begin to benefit from interactions with parents. It is essential that the SLP be aware when this stage is reached so that interactions can be encouraged. 3. Reciprocity. This final stage in the progression usually occurs at some point before the baby is released from the hospital. Now the infant can respond to parental interaction in predictable ways. Failure to achieve this stage, once physiological stability has been achieved, is a signal that developmental deficits may persist. Several instruments are available to assess parent-child communication. These may be used once the baby is ready to participate in communicative interactions. The Parent Behavior Progression (Bromwich et al., 1981) is an instrument that provides a clinician with guidelines for observing a parent’s behavior with the infant to assess what the parent needs in order to improve or maximize the value of the interactions. This instrument rates the parent’s apparent pleasure in the interaction; the sensitivity of the parent to the child’s behavioral cues; the stability and mutuality of the interactions; and the developmental appropriateness of the parent’s choice of actions, objects, and activities. The Observation of Communicative Interaction (Klein & Briggs, 1987), Newborn Behavioral Observations System (Nugent et al., 2007), and Parent-Infant Relationships Global Assessment Scale (Aoki, Iseharashi, Heller, & Bakshi, 2002) are similar instruments. Some danger exists, though, in using formal procedures to assess parent-child communication and family functioning. Although communication is, of course, a two-way street, we do not want to convey to the family in any way that we think they are the problem. As Slentz and Bricker (1992) pointed out, when parent-child interactions or family function are assessed, the implication to family members is often that they have a problem that needs assessment or that their child has a problem because they have a problem. Slentz, Walker, and Bricker (1989) found that the most threatening aspect of early intervention for parents of handicapped children is the assessment of the family. Mahoney and Spiker (1996) discuss similar concerns. The intent of IDEA, through the IFSP, is to provide support to the family in promoting the infant’s development. Although the IFSP mandates participation of the family and identification of their “priorities and concerns,” it does not specifically mandate formal assessments. A simple and effective way to find out about family priorities and concerns is to ask. Slentz and Bricker (1992) suggested that the time it would take to do extensive formal assessment of family functioning is better spent developing a relationship with the family and giving them the opportunity to talk at length with the clinician about the frustrations and joys of raising their baby. This formation of an alliance with the family is more likely to lead to valid insights into their strengths and needs than will misguided attempts at pseudoscientific assessment. Cripe and Bricker (1993) have developed the Family Interest Survey, not to evaluate the family, but to simply find out what they think about their child’s needs. It is intended to be a nonjudgmental means of identifying areas of the family’s interest in both intervention goals and social services and can help the SLP see the family’s perspective on the child’s needs and the services required to provide for them. The How Can We Help survey (Child Development Resources, 1989) is a similar instrument. This survey appears in Appendix 6-5. A recent innovation in the care of the medically stable infant in the NICU is “kangaroo care” (Rossetti, 2001; Ruiz-Palaez, Charpak, & Cuervo, 2004). This technique involves skin-to-skin contact between parent and child during the NICU stay. Parents are encouraged to swaddle the infant to their unclothed chest for about 30 minutes each day. The method has been shown to be associated with decreased length of hospital stay; shorter periods of assisted ventilation; increased periods of alertness; and, perhaps as importantly, with an enhanced sense of nurturance of the child on the parent’s part (Dodd, 2005; Ruiz-Palaez, Charpak, & Cuervo, 2004). This technique seems to have great potential for improving parent-child interactions during the infant’s first days, and can be used as part of the preparation for oral feeding, as we discussed earlier. Still, the very sick neonate may not be ready to take advantage of interactions with parents during the period of acute illness for some time after birth. When this is the case, SLPs can still encourage one important activity in parents: we can help parents to learn to observe their babies and, specifically, to identify states the baby is exhibiting. Learning to identify the baby’s state will be very useful for parents when the time arrives to begin communicative interactions with the baby. Babies are only receptive to interactions in certain states. A parent who can recognize these states and use them as interactive opportunities will have a better chance to engage the baby’s attention and elicit reciprocity. Brazelton (1973) gave a description of the various states seen in the healthy newborn. Each state carries implications for the kinds of caregiving activities that can go on when the infant is in that state (Blackburn, 1978). These states and their implications are summarized in Table 6-1. Table 6-1 *”State” is a group of behaviors that regularly occur together, including (1) bodily activity, (2) eye movement, (3) facial movement, (4) breathing pattern, and (5) responses to stimuli. Adapted from Blackburn, S. (1978). State organizations in the newborn: Implications for caregiving. In K.E. Barend, S. Blackburn, R. Kang & A.L. Saetz (Eds.), Early parent-infant relationships. Series 1: The first six hours of life, module 3. White Plains, NY: The National Foundation/March of Dimes. We can facilitate parents’ identification of the infant’s state by encouraging them to observe their babies and by talking with them about what they see. We can use the behaviors listed in Table 6-1 to distinguish deep sleep from light sleep, for example, and discuss what the parent would do differently, depending on which type of sleep was observed. We also can encourage parents to learn to distinguish among the various waking states and ask similar questions about these. Although the very sick neonate may exhibit few states of alertness, the parent can be encouraged to observe alertness in other babies in the NICU and to identify the fleeting alert states that do occur in the baby who is still in the Turning In stage. When more frequent alert states do emerge, the parents will be ready to recognize and take advantage of them. Hussey-Gardner’s Understanding My Signals (1999) is also helpful for this purpose. Rossetti (2001) suggests that another way to increase the parents’ role with the newborn in the NICU is to encourage the parent to participate in charting the child’s behavior. The SLP can discuss this option with other staff and try to make them understand the advantages of enlisting the parents’ help in the big job of keeping the copious records required in the hospital. Not only will the parents feel more a part of the baby’s care team, but charting can help them learn to be better observers of the child’s behavior, a skill that will serve them well throughout the child’s development.

Assessment and intervention in the prelinguistic period

Family-centered practice

Service plans for prelinguistic clients

Risk factors for communication disorders in infants

Prematurity and low birth weight

Genetic and congenital disorders

Assessment and intervention for high-risk infants and their families in the newborn intensive care nursery

Feeding and oral motor development

Assessment

Management

Hearing conservation and aural habilitation

Child behavior and development

Assessment

Management

Parent-child communication

Assessment

Assessing infant readiness for communication

Assessing parent communication and family functioning

Management

State

Behaviors

Implications for Interaction

Deep sleep

Little possible, adults will do better to wait to feed or interact until child arouses naturally

Light sleep

Makes up largest part of newborn sleep pattern; brief fuss sounds may cause adults to try to feed, rouse, or interact with babies before they are ready.

Drowsy

Infants left alone in this state may return to sleep, but if parents provide something for the baby to look at, listen to, or suck on, baby may be aroused to a more responsive state.

Quiet alert

Providing something for baby to look at, listen to, or suck may maintain this state, which is ideal for interaction.

Active alert

Parents can cuddle and console to bring baby to a less aroused state.

Crying

Tells parents the child has reached his or her limits; needs to be fed or consoled.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Assessment and intervention in the prelinguistic period