CHAPTER 58 Auditory Language Mapping

As described in Chapter 57, electrical stimulation mapping of language cortex is a useful adjunct for a variety of neurosurgical procedures. It is used to demarcate and subsequently minimize risk to language function in patients with temporal and extratemporal epilepsy, primary and secondary brain tumors, cortical and subcortical vascular lesions, and deep-seated lesions involving temporal approaches.

Initially, stimulation mapping was used to identify motor and sensory cortex.1 In the 1950s, Penfield and colleagues began to use mapping techniques to identify language cortex.2–4 Since that time, language mapping has become standard practice for many language-dominant temporal cortical resections. Naming function is clinically important in epilepsy because it correlates with patient complaints such as difficult word finding (“tip-of-the-tongue” phenomenon), losing things or going back to check on things, forgetting things that patients have been told, or forgetting names.5,6 Conventional assessment of word finding involves the use of visual naming tasks, such as the Boston Naming Test.7 Patients are asked to name particular objects depicted in line drawings. Removal of cortex within 1 cm of sites identified by such techniques has been shown to result in postoperative naming decline.8,9 However, a postoperative decline in naming has been observed even in patients who have undergone cortical mapping with sparing of temporal visual naming sites.10

The original rationale for using visual naming in cortical language mapping was based on the observation that visual object naming is impaired in virtually all aphasic syndromes; thus, it was reasoned that preservation of cortex necessary for object naming would reduce the probability of postoperative aphasia.11 However, decades of experience with surgery for temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) has demonstrated that postoperative aphasia is extremely rare; rather, the primary concern with respect to postoperative language function after temporal lobe resection is a decline in word finding.12,13 In the context of imperfect results with a visually based naming task, an auditory-based naming task was developed by Marla Hamberger, the epilepsy neuropsychologist at Columbia University, and her colleagues. Instead of using illustrations of nouns, verbal descriptions are read to the patient. For example, instead of showing the patient a picture of a crown, the phrase “what a king wears on his head” is said or “a device used for taking pictures” is said in place of an illustration of a camera. The goal of these studies is to use an auditory naming task to identify cortex that would result in aphasia if resected in the hope of eliminating word-finding deficits after temporal lobe surgery.

Distribution of Auditory Versus Visual Naming Sites

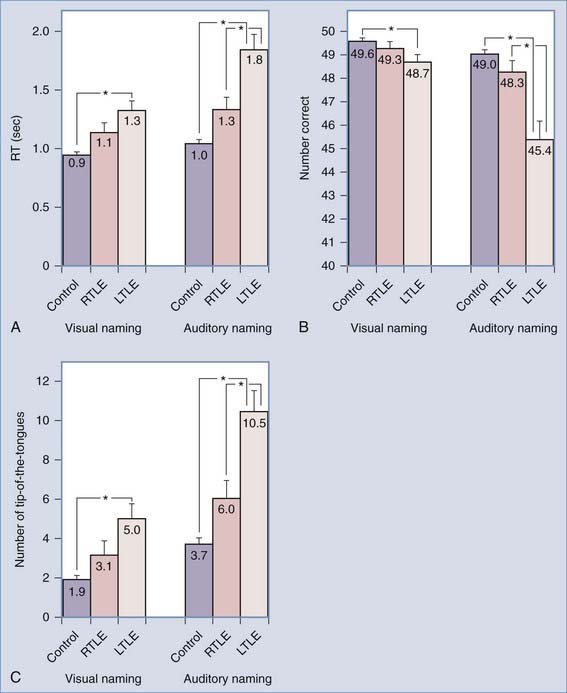

By bypassing the bilateral visual system, auditory naming tasks may be more sensitive to left-sided language function. In a comparison of patients with left TLE (a population with expected naming difficulty) and patients with right TLE (a population with no expected naming deficits), those with left-sided disease performed more poorly than did patients with right-sided TLE on both visual and auditory naming tasks, but the difference was much more marked when auditory tasks were used (Fig. 58-1).14

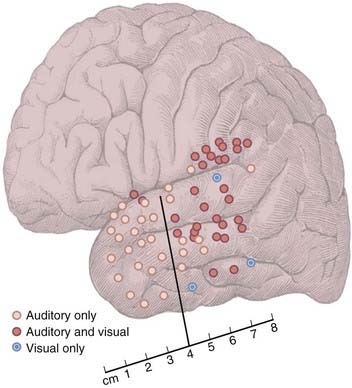

Because auditory naming is disproportionately impaired in patients with left TLE, Hamberger and colleagues hypothesized that the auditory naming function is supported by the dominant anterior temporal lobe.15 An initial study of 20 patients supported this hypothesis. The results of mapping revealed three types of positive naming sites: (1) sites at which stimulation impaired auditory but not visual naming (auditory only), (2) sites at which stimulation impaired both auditory and visual naming (dual sites), and (3) sites at which stimulation impaired visual but not auditory naming (visual only). Of the 18 patients in whom naming sites were found, 15 exhibited auditory-only sites, 3 exhibited visual-only sites, and 11 exhibited both auditory-only and dual (or visual-only) sites. In patients in whom naming sites were identified, the number of naming sites (auditory only, visual only, or dual) identified within an individual patient ranged from one to eight per patient (auditory-only sites, one to four per patient; visual-only sites, one per patient; dual sites, one to five per patient).

Figure 58-2 shows the distribution of naming sites as a function of stimulus modality across patients. In accordance with the proposed hypothesis, stimulation at sites along the anterior surface of the temporal lobe disrupted auditory but not visual naming. In contrast, stimulation of most sites in the posterior region disrupted both auditory and visual naming. These results demonstrate that the anterior temporal lobe is functionally important for auditory more than visual naming.15

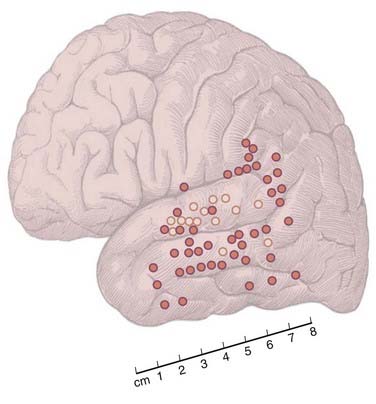

Subsequent analysis of auditory naming errors elicited by stimulation in the temporal region revealed an anatomic distinction between sites associated with different types of errors. Specifically, most sites at which stimulation induced receptive errors/errors in auditory comprehension clustered in the middle to posterior portion of the superior temporal gyrus (i.e., corresponding to Brodmann’s area 22 or the auditory association cortex), whereas most sites at which stimulation elicited expressive errors/errors in word retrieval were located outside this region and were found to be scattered along the lateral temporal and temporoparietal cortex (Fig. 58-3).16

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree