Autosomal Recessive Benign Myoclonic Epilepsy of Infancy

Federico Zara*

Fabrizio A De Falco†

*Laboratory of Neurogenetics, Department of Neuroscience and Rehabilitation, Institute G. Gaslini, Genova, Italy

†Department of Neurology, Loreto Nuovo Hospital, Napoli, Italy

Introduction

The nosologic classification of epilepsies with myoclonic manifestations occurring in infancy and early childhood has always been difficult (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8). In fact, myoclonic events may be nonspecific manifestations occurring in a variety of epileptic disorders.

Epileptic syndromes of infancy and early childhood presenting with myoclonic manifestations include complex phenotypes characterized by different type of seizures, variable neurologic symptoms, and often a poor prognosis, such as early myoclonic encephalopathy, West syndrome, Lennox–Gastaut syndrome (LGS), severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy (SMEI), myoclonic-astatic epilepsy (MAE), and phenotypes in which myoclonic seizures are the prominent clinical feature with absence of other types of seizures or neurologic signs, such as the benign myoclonic epilepsy of infancy (BMEI) (9).

This heterogeneous group of disorders includes symptomatic forms characterized by pre-existent brain damage, usually acquired in the prenatal or neonatal periods or in infancy and forms without evidence of brain pathology before the onset of the seizures, likely of genetic origin. Except for the SMEI, the mode of inheritance and the genetic etiology of these forms are largely unknown.

However, the clinical heterogeneity and the sporadic nature of these disorders have complicated their classification into homogenous syndromic entities and many cases of myoclonic epilepsy with onset in infancy remain unclassified.

Among these disorders, familial myoclonic epilepsy with onset in infancy (FIME) is a peculiar form characterized by autosomal recessive inheritance, myoclonic seizures associated to generalized tonic-clonic seizures persisting into adulthood if not controlled by an appropriate treatment, normal psychomotor development, and benign outcome (10,11) (Table 10-1).

TABLE 10-1. Clinical features of eight FIME patients | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Clinical features

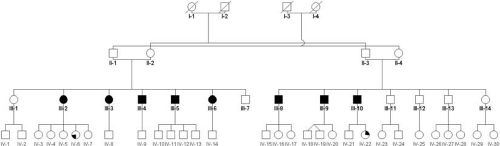

FIME was observed in eight patients belonging to a large Italian family (Fig. 10-1). Clinical features are homogeneous among patients with slight differences in the clinical onset and occurrence of febrile seizures.

Clinical Onset

The disease could begin with afebrile generalized tonic-clonic seizures between the 4th and the 7th months of age (patients III-2 to III-5) or with myoclonic seizures between the 12th and 18th months (patients III-8, III-9, and III-10). In one patient, it began with febrile seizures at the age of 3 years (patient III-6).

Seizures

Febrile seizures occurred between 5 and 36 months of age, in five affected individuals, all in branch I from the first offspring (patients III-2 to III-6).

Myoclonic seizures (MS) represented the dominant seizure type and were present in all the affected subjects from both branches of offspring, showing the same clinical features. They appeared between 5 and 36 months of age and persisted to adulthood in all patients. Clinical features varied with age. In childhood, MS were spontaneous and could be erratic, bilateral or massive. They occurred isolated or in clusters, several times a day, and could last for many hours (sporadic myoclonic status epilepticus), with preserved consciousness, sometimes preceding a convulsive seizure. During adolescence, MS occurred several times a week, sometimes lasting 30 min or longer, or persisting until the appearance of generalized tonic–clonic seizures (GTCS), which marked the end of the myoclonic status. During youth, myoclonic attacks more often had a localized pattern. They were spontaneous and facilitated by fatigue or drowsiness, or induced by intense and persistent stimulation (acoustic stimuli or variations in light intensity) or by repetitive movements. MS could have onset from the hands while peeling potatoes or from the legs after long walks. One subject reported the onset of myoclonic jerks in the legs culminating in a GTCS after standing up in back of a truck while riding over rough terrain during military service. After persistent light stimulus, patients complained of involuntary rapid eyelid and eyeball movement and almost none of the subjects tolerated intense green and thus, could not take a walk through the woods. All the subjects had learned to avoid situations triggering myoclonic jerks and recognize those attacks that preceded a generalized seizure. The trigger stimuli in our patients were unlike those of the reflex myoclonic epilepsy of infancy described by Ricci et al. (12) in 1995, where surprise appeared fundamental in triggering attacks, regardless of the type of stimulus used. In all types of reflex epilepsy the unexpected nature of the stimulus is the main factor in precipitation (13), while in our family the MS was induced by persisting trigger stimuli.

GTCS occurred in all affected subjects, with onset in early infancy in branch I (patients III-2 to III-6) and between 4 and 8 years in branch II (patients III-8 to III-10). They were spontaneous or followed a prolonged myoclonic status. GTCS were more frequent in infancy and in adolescence, but persisted even into adulthood, except for patient III-4, who presented his last GTCS at 19 years of age. A patient (III-6) presented a true status convulsivus after appendectomy and repeated GTCS at delivery.

Other Clinical Features

The neurologic examination was normal in all affected individuals and neuroradiologic investigations (cranial C T and/or MRI), carried out on five patients were unremarkable. All subjects had normal psychomotor development and had no signs of cognitive deterioration. All were married with children.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree