Basic Traumatic Injuries and Definition of Common Lesions

Ana Rubio

David Fowler

In this chapter, we describe the basic types of injuries produced by physical forces as they relate to neuropathology, including both external and internal lesions, gross and microscopic findings. A general review of traumatic injuries can be found in many forensic1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 or neuropathology8, 9, 10, 11, 12 texts. A question often asked in court pertains to the pathologist’s estimation of the age of the injuries. The tissue reaction and healing process start immediately after the injury, but the tempo varies according to the causative force, the location of the wound, and the pathophysiologic condition of the subject at the time of the injury. In addition, and of importance in forensic neuropathology, the reaction to injury and healing of brain tissue may come to a halt when an individual is kept alive on a respirator but the brain is not being perfused and is undergoing autolysis. This is because the brain tissue does not receive the blood supply necessary for the inflammatory reaction to progress.

BLUNT FORCE INJURIES

Blunt force injuries are caused by kinetic energy. The energy is transferred to the body either by a moving object or by the body striking a surface. If the amount and rapidity of energy transfer is greater than that part of the body can adapt to, an injury occurs. Blunt force injuries have some similarities to missile injuries, but in blunt force injuries, the velocity is lower and the size of the object is usually larger than in projectile injuries. Although we separate blunt force injuries into abrasions, contusions, and lacerations, an individual injury is frequently a mixture of more than one type.

Abrasions

Abrasions are blunt force injuries affecting the skin surface. They are usually produced by forces directed either tangentially to the body surface (graze, scratch, or brush abrasion; Fig. 4.1), or perpendicularly to the skin, generating heat or squeezing the epidermis (crushing abrasion; Fig. 4.2). In grazes, the outer layers of the epidermis are removed, and the direction of the force can be determined by observing the direction of the skin tags (Fig. 4.3). In crushing abrasions, the skin appears thin and has a red to orange coloration. Crushing abrasions may have a central laceration (Fig. 4.4), especially when the affected skin overlies bone, and the lesion approximates the size and shape of the object. Some crushing abrasions actually display an imprint of the impacting object (Figs. 4.5 and 4.6).

FIG. 4.1. A group of scrape abrasions is present on the anterior aspect of the foot of a pedestrian hit by a vehicle. |

FIG. 4.2. A crush abrasion is present on the exposed skin of the abdomen; the medial edge continues with an imprint abrasion suggestive of the edge of a tire. |

Unbroken falls may produce facial abrasions in the protruding skin (Fig. 4.7)

Head hair (particularly in individuals with long, thick, or abundant hair) may protect the scalp from abrasions.

Very superficial abrasions may not be immediately visible and, if the skin remains damp, may not show for hours. The typical skin abrasion seen in forensic pathology is enhanced by postmortem drying (Figs. 4.8A and B).

Postmortem abrasions lack a tissue reaction and the skin appears thin, translucent, and yellow, simulating parchment paper.

Abrasions are not seen in the internal organs.

Contusions

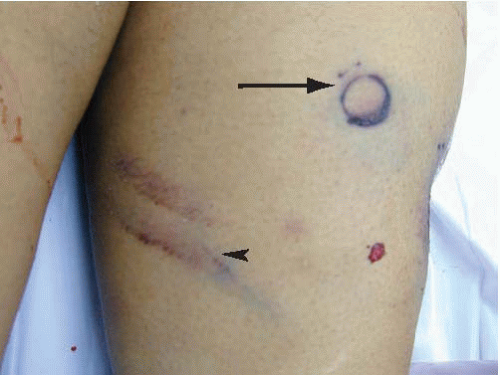

Contusions (bruises) result from blood exiting ruptured dermal vessels and accumulating below an intact epidermis. Contusions manifest as subcutaneous discolorations of varying sizes, shapes, and colors. When the impacting object is small or thin, the vessels below the point of impact collapse, the vessels at the edge may stretch and break, and the resulting hematoma outlines the shape of the object (Fig. 4.9). Small hemorrhages (1 mm or less in diameter) are called petechiae. A localized group of petechiae can be associated with blunt forces and need to be differentiated from asphyxia-related petechiae and from Tardieu hemorrhages (in areas of postmortem lividity). The characteristics of a contusion, such as size, color, and sharpness of the edges, depend on many factors, including the amount and type of force and characteristics of the object, the anatomic location of the lesion (thickness of the skin, proximity to the bone under the skin), the individual’s age (elasticity and fragility of the skin and vascular walls) and state of health (liver, renal, and hematologic function), and the depth of the hemorrhage (as in the dermis or subdermis), among others.13

FIG. 4.4. A linear laceration in the center of a round abrasion is a typical finding following a forceful impact on a flat surface such as the ground. |

Because of the close proximity of the skull to the skin, contusions of the head may protrude (“goose egg”; Fig. 4.10).

Contusions may be hard to see in a hair-covered scalp. Reflection of the scalp during autopsy may reveal scalp or subgaleal hematoma.

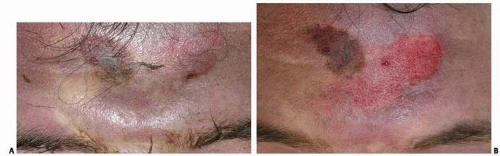

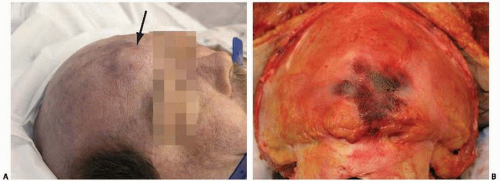

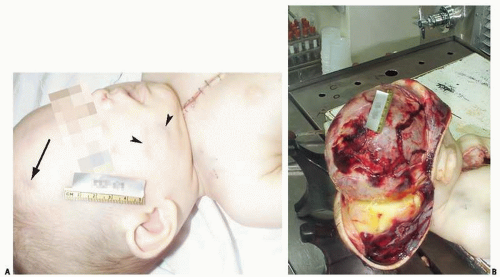

Not all external contusions can be seen through the skin, or they may be very faint, even in individuals with pale skin (Figs. 4.11A and B).

Frank swelling of the scalp is common with diffuse scalp contusions.

Pattern contusions can be seen in superficial bruises (when the hemorrhage is deep, the edges tend to blur) and are produced by sharply delineated objects, such as the edge of a ridged shoe, a ribbed neck collar, a tire running over the skin (Fig. 4.12), or the edge of a gun. Given that the skin is elastic, an exact imprint is usually not seen, but pattern matching can be done, and documented by taking photographs of the injury and the object at the same scale.

The appearance and location of some bruises change over time. With time, blood accumulated in facial contusions seeps through the tissue planes by gravity and distributes in lower areas or in areas with more laxity of the skin, resulting in contusions away from the point of impact (Fig. 4.13).

As in the case of abrasions, the appearance of contusions evolves postmortem, and they may be more easily seen at the end of the autopsy, as the intravascular blood drains from the surrounding tissue and the entrapped free blood becomes more apparent.

Estimation of the age of a contusion based on its gross appearance is unreliable. Bruises may not appear immediately after the injury, and deep bruises may not show for 12 or 24 hours. Typically, the color of a recent bruise (less than 1 day) is red, purple, black, or blue (Fig. 4.14) and progresses to dark blue, purple, or brown (1 to 3 days), to green (4 to 7 days), and to yellow or brown (1 to 2 weeks) (Fig. 4.15), but dating of bruises based on gross appearance is unreliable.14 Yellow can be seen macroscopically as soon as 18 hours after the injury.13 The color of the bruise depends on the amount of extravasated blood, the depth of bleeding, the color and thickness of the skin over the contusion, and the amount of time from the impact. We have seen recent, deep bruises with a green to brown coloration. There is extensive inter- and intraindividual variability both in the healing process and in the observer’s appreciation of color; specifically, the ability to detect yellow in a contusion decreases with the observer’s age.15

FIG. 4.7. The forehead, nose, cheeks, and lips are abraded as the result of an unbroken fall to the ground, where the individual remained unconscious and was later pronounced dead. |

Brain Contusions

Brain contusions are characterized by damage to the surface of the brain (Fig. 4.16), commonly affecting the crests of the gyri but sparing the depth of the sulci (e-Fig. 4.1). Deep contusions may involve the entire cortex and even the subcortical white matter.8, 9 On cross-section, contusions have a pyramidal shape, with the base located superficially and the tip internally (Fig. 4.17). The injured

brain swells andmay undergo complete or incomplete necrosis (characterized by liquefaction) and hemorrhage. The amount and type of hemorrhage determines the appearance of recent wounds. Most acute contusions are either diffusely hemorrhagic or contain hemorrhagic streaks perpendicular to the brain surface (Fig. 4.17). Subarachnoid hemorrhage commonly overlies contusions (e-Fig. 4.2), and the pia over the contusion remains intact (unlike lacerations).

brain swells andmay undergo complete or incomplete necrosis (characterized by liquefaction) and hemorrhage. The amount and type of hemorrhage determines the appearance of recent wounds. Most acute contusions are either diffusely hemorrhagic or contain hemorrhagic streaks perpendicular to the brain surface (Fig. 4.17). Subarachnoid hemorrhage commonly overlies contusions (e-Fig. 4.2), and the pia over the contusion remains intact (unlike lacerations).

There are two basic types of cortical contusions. Coup contusions are located underneath the area directly impacted by the traumatic force. Contrecoup (secondary) contusions result from the buffeting of the moving brain against the unyielding bone as it hits a surface or the ground. These may be found in regions of the brain opposite the point of impact (e-Figs. 4.3A-C), but most commonly involve the tips and inferior surfaces of the frontal and temporal lobes (e-Fig. 4.4). These regions are more vulnerable to contrecoup contusions because they ride on rough bony ridges at the anterior and middle fossae of the skull. Contusions may be admixed with lacerations. Contrecoup contusions are almost always associated with falls, and the contrecoup contusion is usually larger than its corresponding coup (e-Figs. 4.3B and C). Contusions need to be

differentiated from brain infarcts or other causes of cortical hemorrhages, such as vascular malformations, infections, or tumors. With time, the brain parenchyma undergoes liquefaction necrosis, and the hemorrhage resolves. Remote contusions (plaque jaune) are characterized by a ring of rusty, shrunken tissue surrounding a cystic defect in the surface of the brain. Additional illustrations and descriptions of brain contusions are presented in Chapter 7.

differentiated from brain infarcts or other causes of cortical hemorrhages, such as vascular malformations, infections, or tumors. With time, the brain parenchyma undergoes liquefaction necrosis, and the hemorrhage resolves. Remote contusions (plaque jaune) are characterized by a ring of rusty, shrunken tissue surrounding a cystic defect in the surface of the brain. Additional illustrations and descriptions of brain contusions are presented in Chapter 7.

FIG. 4.11. Photographs of the head of a 5-month-old child before (A) and after reflecting the scalp forward (B). A faint pattern contusion, consistent with a bite mark, was present on the right cheek (arrowheads) and a faint contusion on the right forehead (arrow), but no other traumatic injuries were obvious externally. The scalp had diffuse swelling and a contusion over the top and right frontoparietal area and overlying skull fractures produced by homicidal blunt force injuries.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|