B

izarre or altered behavioral patterns traditionally are felt to relate to psychiatric disorders or generalized delirium from drugs, toxins, or metabolic imbalances. However, some specific neurologic conditions present with remarkably consistent behavioral abnormalities. These conditions have equally consistent anatomic substrates, and, when identified by an astute diagnostician, they suggest specific causes and treatments. In

this chapter, five conditions are discussed, each with a prominent behavioral and seemingly psychiatric presentation but with a pathologic basis related to a specific neurologic dysfunction. These conditions are temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), fluent aphasia, Wernicke encephalopathy, transient global amnesia, and herpes encephalitis.

These strange disorders are not rare, and their complexity often relates not to management problems but to accurate identification. The topic is thus particularly pertinent to the nonneurologist, who is most likely to be the first person to interview and evaluate these patients.

ANATOMIC BASIS—PAPEZ CIRCUIT

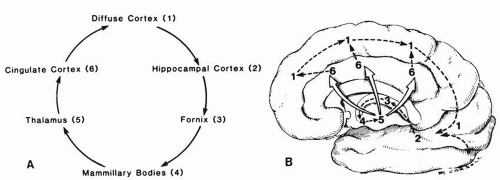

It is well recognized that the ability to recall and engender memories is intimately linked to the emotional makeup of such memories. Furthermore, several clinical conditions demonstrate combined and prominent memory-emotional alterations, suggesting that the anatomic basis of these two functions may be linked. In 1937, the neuroanatomist Papez published a treatise describing an anatomic circuit that linked those nuclei and paths that appear important to many aspects of emotional-behavioral integration. This circuit, the Papez circuit, is probably the most important circuit for clinicians dealing with behavioral abnormalities; familiarity with it allows them to think systematically about the anatomic foundations of behavioral neurology.

The circuit is diagrammed schematically in

Figure 15.1A, with anatomic nuclei and paths identified in the sagittal brain section of

Figure 15.1B. As indicated, the pathway is circular, providing continual reintegration of information. The two focal cortical areas most prominently involved are the cingulate cortex and the hippocampus of the temporal lobe. Diffuse cortical impulses travel into the hippocampus, an area felt to be particularly important to memory and emotional expression. This information travels forward in the fornix path to the mammillary bodies of the hypothalamus and continues to the anterior lobe of the thalamus, and further to the midline cingulate cortex, which finally projects diffusely to cortical regions.

Familiarity with this circuit is useful because disease anywhere along the pathway can be expected to result in aberrant emotional behaviors, although not necessarily the same patterns. This knowledge allows the clinician to focus immediately on a finite number of nuclei and connecting paths to explain abnormal behavioral symptoms that may have a focal

anatomic basis. The term diffuse cortical input is important because toxic and metabolic encephalopathy often present with agitated behavior or a change in personality. The other areas, however, are focal, and identification of disease at these levels can lead to rapid intervention. Reference will be made to this circuit throughout this chapter.

TEMPORAL LOBE EPILEPSY

Also referred to as psychomotor epilepsy and partial complex seizure, psychomotor or psychosensory variety, TLE may manifest itself with intermittent spells of bizarre behavior, including babbling nonsense and frank visual and auditory hallucinations, all related to organic disease of the central nervous system. Differentiation of this disorder from psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia can be difficult, yet it is essential because their treatments are drastically different. Certain specific characteristics are helpful in establishing abnormal behavioral patterns as probable epilepsy, and they are the focus of this discussion.

TLE represents an abnormal electrical discharge that begins in one temporal lobe and usually crosses rapidly to involve both sides of the brain. To recognize TLE in a patient, the clinician should attempt to elicit specific information in four areas. If information in even one of these areas is characteristic of TLE, the diagnosis is suggested.

The distinctive temporal pattern of the spells.

The presence of an aura, a distinctive feeling, or sensation that regularly precedes or begins the spells.

The presence of peculiar motor behaviors called automatisms.

The specific type of loss of consciousness.

The distinctive temporal pattern of TLE refers to repeated, but intermittent, and paroxysmal changes in behavior, not necessarily linked to any emotional provocation. The behavioral changes are brief, lasting seconds to minutes. Often, before any visible behavioral change can be appreciated by an observer, the patient experiences a stereotypic and fixed sensation, known as an epileptic aura. The aura represents the beginning of the seizure and can help in localizing the focus, or source, of the seizure activity. The aura may be olfactory, in which the patient suddenly smells a strange, often pungent odor, or it may be a gustatory sensation or a strange abdominal “butterflies” feeling, also called epigastric rising. Emotional changes of sudden unfamiliarity with one’s environment (jamais vu) or sudden intense familiarity with the surroundings (déjà vu) are seen, and there may be intense and vivid auditory or visual hallucinations. The aura and the area of the temporal lobe cortex that are felt to relate to the seizure focus are listed in

Table 15.1. The presence of this stereotypic aura and sudden unprovoked change in behavior help to quickly identify a patient with TLE. The aura is sensed by the patient and is not identified by the clinician except by interview. The patient may not necessarily link the strange aura to his

spells, so that information must be solicited specifically.

▪ SPECIAL CLINICAL POINT: The very first perceived abnormality related to a seizure has key importance to localizing the source of the epilepsy, so careful interviewing of a typical spell, step-by-step is essential.

The presence of automatisms is also useful in the diagnosis of TLE. These activities appear as the seizure spreads in the amygdala region of the temporal lobe. The movements may range from rather primitive movements (lip smacking, eye blinking, or chewing motions) or may be highly complex (dressing and undressing, piling objects on top of one another). These are stereotypic and rather fixed from one spell to another, so a detailed record of two or more episodes helps to establish the pattern of behavior.

The peculiar characteristic of the loss of consciousness seen in TLE is also helpful. After the aura, which the examiner cannot see unless it involves automatisms, there is a sudden loss of contact with the environment in TLE. Unlike patients who have other generalized seizures, these patients only rarely fall to the floor, shake all over, urinate, or bite their tongue. Instead, when they lose consciousness, they maintain body tone and may walk around but “in a daze, out of contact” with the environment. When the spell is over, the patient is usually amnestic for the seizure, except that he may recall its beginning and be able to recount, if specifically asked, the details of the aura. Immediately after the spell, the patient is usually confused and sleepy. If restrained during this period, he may strike out randomly at people who try to assist. However, these patients are generally not violent in a goal-directed manner, either during or after their seizures. As strange as their behaviors may be, focused violence, such as tracking a person with a gun or retrieving a kitchen knife out of a drawer and stabbing a victim, is far outside the repertoire of TLE.

Table 15.2 serves as a summary and outlines additional guidelines for differentiating TLE episodes from psychotic bizarre behaviors of schizophrenia. These patterns are clinically useful, although no absolute rules hold true. The following example demonstrates that TLE patients can be misdiagnosed.

Case: A 16-year-old boy on the psychiatric unit with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and hallucinatory behavior is evaluated by the neurologist because of a single generalized seizure. On being interviewed, this patient says, “It’s just like before, but this time much worse.” Several times each week, this patient sees “the man,” a blurry but discernible bearded man who beckons him forward verbally. As this happens, everything in the patient’s environment becomes suddenly more distinct, clearer, and more colorful, with a clear sense of familiarity and warmth. Then a strange feeling of dread and a “fog” come over the patient, who

then appears to lose touch for approximately 5 minutes. He has no recollection of this period of losing touch, but his family says that he walks around in the house mumbling strange noises that are sometimes prayers, and at the same time he bows his head back and forth in a seemingly ritualistic manner. After this, he lies down and sleeps for approximately 2 hours. The same stereotypic pattern occurred immediately before the generalized seizure.

This patient again shows the stereotypic aura, which is hallucinatory this time, along with the sense of emotional familiarity with the environment. Stereotypic repetition of episodes and the automatisms with amnesia and sleepiness afterward strongly suggest TLE. In regard to this latter episode in which there was a generalized motor seizure with bilateral shaking, this pattern can be seen with TLE when the seizure activity spreads throughout both sides of the brain. An EEG study with nasopharyngeal recordings demonstrated abnormal epileptiform activity. On medication, the patient has shown remarkable improvement. This case demonstrates the important interface between psychiatric symptoms and clear focal neurologic disease.

▪ SPECIAL CLINICAL POINT: The distinctive behavioral manifestation of these seizures is a stereotypic loss of contact with the environment, often a “dazed” look while otherwise apparently awake.

ANATOMY AND CLINICAL FINDINGS

The anatomic lesions of TLE naturally relate to the temporal lobe and, depending on the area damaged, will give rise to different auras (

Table 15.1). As can be seen, some of these nuclei are primary portions of the Papez circuit and the others have direct input into the circuit.

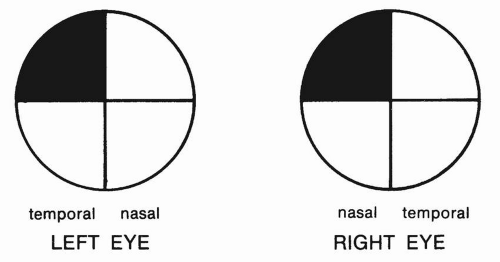

In examining a patient with TLE, if there is a tumor, stroke, or space occupying lesion, a finding may include a homonymous hemianopia, or a homonymous quadrantanopsia, especially in the superior fields (

Fig. 15.2). Because the visual fibers pass through the temporal lobe en route to the occipital cortex, the superior quadrantanopsia should be specifically sought.

Much has been written about psychopathology in patients with TLE. Although the seizures and bizarre behavior are intermittent, interictal or between-seizure abnormalities are often attributed to TLE. Problems such as sedation, inattention, and depressed mood may be seen as dose-related side effects of antiepileptic medications. If toxicity can be ruled out, the most common psychiatric problem in epilepsy is depression. Although not specific to TLE, research suggests rates of depression as high as 75% in some clinical samples. Paradoxically, depression may appear after seizure control is accomplished, suggesting that seizures, like electroconvulsive therapy, may serve to elevate mood, possibly through opioid mechanisms.

Aggressive behavior is often attributed to TLE. There is, however, no good evidence of a disproportionate level of aggressive or violent behavior in TLE or epilepsy. Aggressive behavior may be seen following a seizure, but it is typically nondirected and random, occurring when the patient is aroused or restrained. The hypothesis that TLE is characterized by a distinct personality profile has not been supported by recent research. However, psychiatric signs and symptoms in general are seen more commonly in TLE than in other forms of epilepsy, particularly in patients with severe, uncontrolled TLE.