INTRODUCTION

Behavioural symptoms are common in patients with Alzheimer’s dis-ease (AD) and contribute substantially to morbidity1–3.As many as 80% of Alzheimer’s patients develop behavioural changes, typi-cally with increasing frequency as the disease progresses4. Estimates range from between 30–50% for delusions or hallucinations and up to 70% for agitated or aggressive behaviors5. Behavioural symptoms have long been known to contribute to caregiver distress5,6.More recent work has found that 46% of caregivers cite dementia-related behaviours as a primary reason for institutionalization7. Behavioural symptoms in patients with AD significantly increase direct costs of care, a cost which may be lessened by appropriate psychopharma-cological management8,9. In this chapter, descriptions of the most common behavioural disturbances observed in AD and other demen-tias are provided, followed by examples of common measurement tools used in research to study these symptoms. The currently avail-able pharmacological options for treating the behavioural symptoms of dementia are then reviewed, highlighting areas in which data can help guide targeted treatment of specific symptoms. This chapter con-cludes with a discussion of general treatment principles, intended to aid clinicians in an era when there are not clearly benign and bene-ficial treatment options available to address the ongoing severe and complex behavioural symptoms of dementia10.

The psychosis of AD typically consists of delusions, misiden-tification syndromes and, less frequently, visual or auditory hallucinations3,11. Delusions of dementia tend to be simple, non-bizarre and often reflective of misinterpretation of the environment. The delusion of stealing is most prevalent, followed by persecutory delusions, delusions of reference, infidelity, grandiosity and somatic delusions12. Delusions are more common in moderate stages of the illness and are associated with greater cognitive impairment. Likewise, hallucinations are rare in the early stages of AD and become more common in the later stages13. The most common misidentification syndromes include failure to recognize one’s home (‘this is not my home’ phenomenon), the belief that strangers are living in the home (phantom boarder syndrome) and imposter loved ones (Capgras phenomenon)14. Psychosis in AD clearly represents a syndrome distinct from schizophrenia in elderly patients, with only rare presence of first-rank Schneiderian symptoms and a higher rate of eventual remission of psychosis. In contrast to treatment of older adults with schizophrenia, antipsychotic treatment of psychosis in AD, described in detail below, is characterized by lower doses of medication, shorter duration of treatment and greater vulnerability to extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS).

Agitation in dementia has been defined as inappropriate verbal, vocal or motor behaviours not judged by an outside observer to result directly from the needs or confusion of the agitated indi-vidual. Increasing agitation is associated with advanced dementia, pre-morbid aggression and rapid decline. AD patients often also develop depression and anxiety, which in general are managed with antidepressant medications. While these topics will not be addressed in depth during this chapter, it is important to note that, similar to the contrast between schizophrenia and the psychosis of AD, substantial differences exist between primary mood and anxiety disorders ver-sus dementia-related psychological symptoms in terms of aetiology, manifestations and treatment response.

Several standard neuropsychiatric symptom rating scales are used, primarily in research settings, to categorize the common behavioural and psychological symptoms in dementia (BPSD) (Table 53.1). Four of the most widely used general rating instruments include the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI), the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), the Neurobehavioral Rating Scale (NBRS) and the Cohen–Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI). The NPI measures the frequency and severity of 12 psychiatric symptoms on the basis of caregiver report15. The items are delusions, hallucinations, agitation/aggression, depression/dysphoria, anxiety, elation, apa-thy/indifference, disinhibition, irritability/lability, aberrant motor behaviour, sleep disturbance, and appetite and eating disorder. The BPRS measures the severity of 18 psychiatric and behavioural symptoms, typically scored by a trained clinician after a semi-structured patient interview and collection of additional information from caregivers16. The NBRS has 28 items, covering areas including agitation (aggression, agitation, hostility) and psychosis (suspicious-ness, hallucinations, delusions) and is completed by an observer on a 7-point scale17. The CMAI rates the frequency of 29 agitated behaviours in four factors on 7-point scales18.

Table 53.1 Neuropsychiatric symptom rating scales

| Agitated Behavior Inventory for Dementia (ABID) |

| Agitation-Calmness Evaluation Scale (ACES) |

| Alzheimer Disease Assessment Scale, non-cognitive portion (ADAS–noncog) |

| Bech–Rafaelsen Mania Scale (BRMS) |

| Behavior Observation Scale for Intramural Psychogeriatric Patients (GIP) |

| Behavior Rating Scale for Dementia (BRSD)Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer Disease Rating Scale (BEHAVE–AD) |

| Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) |

| Caregiver Burden Questionnaire (CBQ) |

| Clinical Global Impression of Change (CGIC) |

| Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGIS) |

| Clinicians Interview Based Impression of Change plus caregiver input (CIBIC–plus) |

| Cohen–Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) |

| Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM–D) |

| Iowa Caregiver Stress Inventory (CSI) |

| Neurobehvaioral Rating Scale (NBRS) |

| Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) |

| Neuropsychiatric Inventory–Nursing Home version (NPI–NH) |

| Neuropsychiatric Inventory minus 5 ‘mood’ items (NPI–NM) |

| Overt Aggression Scale (OAS) |

| Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale–Excited Component (PANSS–EC) |

| Revised Memory and Behavior Problem Checklist (RMBPC) |

| Screen for Caregiver Burden (SCB) |

| Social Dysfunction and Aggression Scale (SDAS–9) |

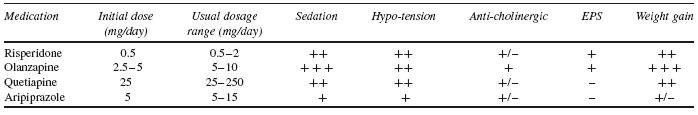

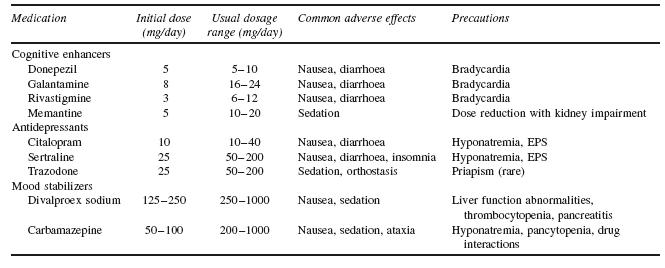

When approaching behavioural disturbances in dementia, the overall preferred approach to management includes: (i) assessing to characterize the specific psychiatric or behavioural symptoms; (ii) developing an appropriate set of nonpharmacological behavioural interventions; and (iii) considering medication treatment if there are immediate safety concerns or insufficient response to behavioural interventions. To date, there are no FDA-approved medications for behavioural management of AD. The largest amount of available evidence studying psychosis and/or agitation associated with dementia suggests a modest efficacy of antipsychotic medications in symptom reduction, in the context of these medications now carrying a ‘black box’ warning regarding use in elderly patients with dementia. What follows is a review of the options available for pharmacological management of behavioural symptoms of dementia. See Tables 53.2 and 53.3 for dosing and side-effect information for agents discussed below.

Efficacy Trials

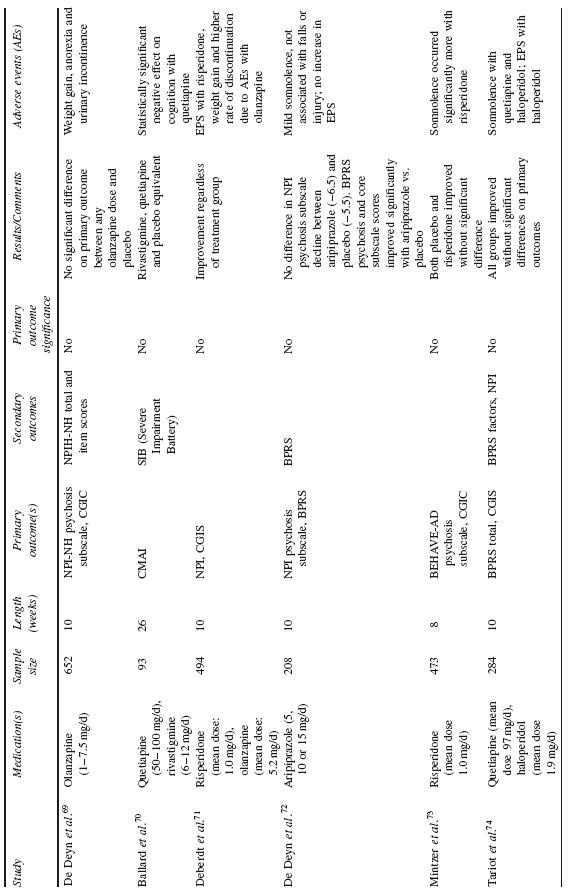

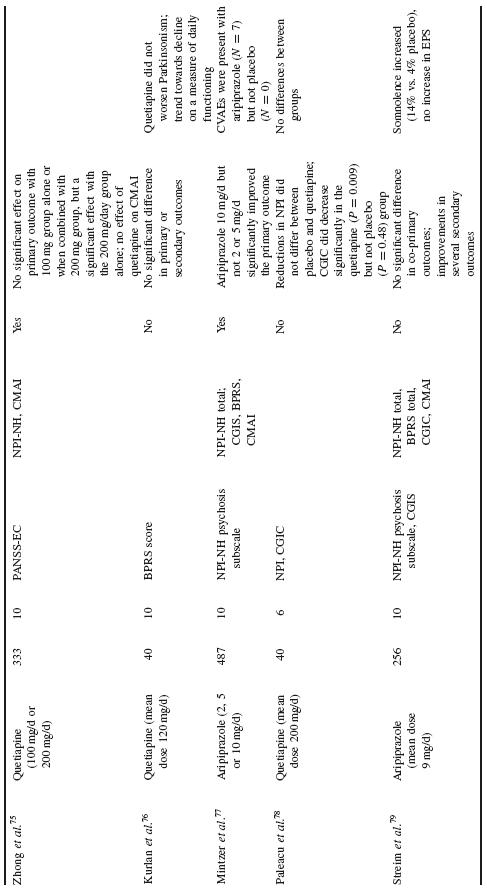

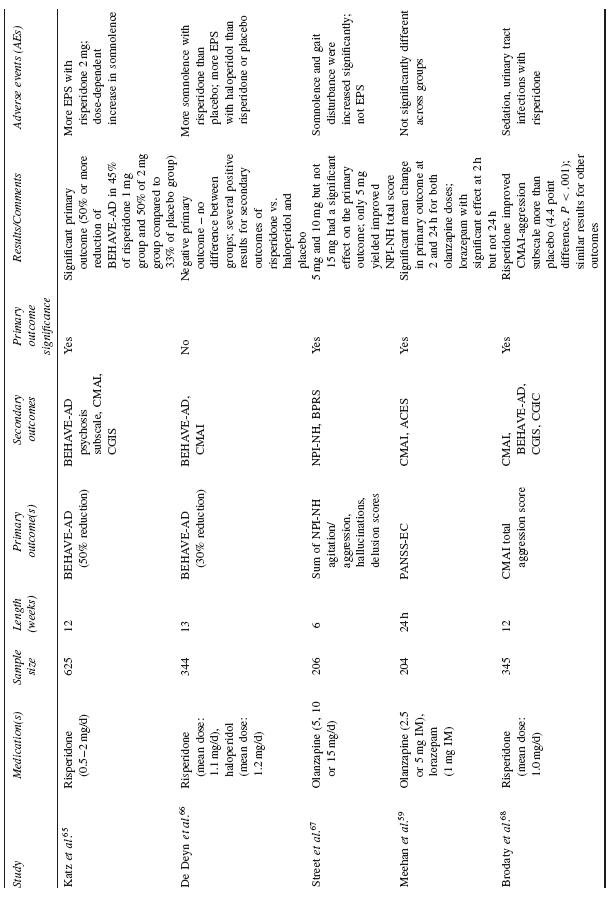

The majority of data examining the psychopharmacological management of behavioural symptoms in dementia exist for the use of antipsychotic medications. Historically, short-term (6–12 week), double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were completed using standardized neuropsychiatric symptom rating scales. These trials have been reviewed in depth in prior publications; here, the reader is referred to Table 53.4 for a summary of published trial results.

In total, efficacy trials of antipsychotic medications have demon-strated a modest benefit for treatment of agitated behaviour and psychosis in AD and other dementias. However, there is heterogene-ity of these findings, with multiple studies also showing no benefit of antipsychotic treatment on primary or secondary outcome measures. Efficacy trials in this arena have typically had high placebo response rates, underscoring the likely importance of several general effects, including the passage of time, increased attention and the expecta-tion of therapeutic intervention. Medication benefit has further been counteracted by adverse events.

As discussed in more detail at the end of this chapter, the deci-sion to use medication and antipsychotic medications in particular should be made in parallel to the process of ongoing optimization of the social and environmental setting of each patient. Concern-ing results from meta-analyses and a recent large effectiveness trial underscore the importance of completing a thorough individualized risk–benefit analysis prior to initiating psychopharmacological man-agement of behavioural disturbances in dementia with antipsychotic or other medications. However, despite the potential risks involved, antipsychotic medications continue to be used to manage particu-larly severe and persistent symptoms in patients with dementia, due in large part to a lack of available alternative with substantial sup-porting evidence.

Meta-Analyses

Schneider etal. reported a meta-analysis of RCT data on the effi-cacy and adverse effects of atypical antipsychotic medications for dementia19. Using a combination of published and drug company data, they reported on 15 RCTs (three on aripiprazole, five on olan-zapine, three on quetiapine and five on risperidone) with a total of 3353 patients assigned to active treatment versus 1757 patients treated with placebo. The majority of patients had AD (87%), were female (70%) and averaged 81 years of age. Mean MMSE score was 11. Eleven trials were conducted in nursing homes and four were completed on outpatients. While approximately half of included tri-als were designed to recruit subjects with psychosis and the other half agitation, the authors found that most studies had a mixture of patients with psychosis and agitation, a subject pool likely to reflect typical clinical populations.

After combining the trials, symptomatic efficacy was observed for aripiprazole and risperidone while olanzapine was not associated with efficacy overall. The available quetiapine trials used different selection criteria and outcomes and thus could not be statistically combined. In general, there was heterogeneity of findings across trials. Larger effect sizes were seen in patients without psychosis (vs. with psychosis), for those in nursing homes (vs. outpatients) and in patients with more severe cognitive impairment (MMSE less than 10). Approximately one-third of subjects dropped out of the trials, without significant difference between drug and placebo groups. The most common adverse events were somnolence and urinary tract infections or incontinence; increased incidence of extra-pyramidal symptoms and gait abnormalities were seen with risperidone and olanzapine. The authors noted a significant risk for cerebrovascular events, especially with risperidone. In addition, an increased risk for overall death was observed, which will be discussed in more detail below.

Two meta-analyses of typical antipsychotic medications found that neuroleptics are significantly more effective than placebo for behavioural disturbances in dementia, albeit with a small effect size and without differential efficacy between particular agents. For example, results from a meta-analysis of six studies comparing thioridazine with another neuroleptic and five studies comparing haloperidol with another neuroleptic, did not show that these two medications differed significantly from comparison medications20. In another meta-analysis, Lonergan etal. examined five RCTs com-paring haloperidol to placebo and found that aggression decreased among patients with agitated dementia treated with haloperidol; other aspects of agitation were not affected significantly in treated patients, compared with controls21.

A recent meta-analysis of patients with psychosis of AD from four large placebo-controlled clinical trials of risperidone in demen-tia demonstrated that risperidone significantly improved scores on the BEHAVE-AD Psychosis subscale and CGI scale compared with placebo22. Secondary analyses demonstrated that patients with more severe symptoms showed a more pronounced response to treatment with risperidone compared with placebo than those patients with less severe symptoms. Extra-pyramidal symptoms and somnolence were more frequent with risperidone than placebo (p=0.04). Cerebrovas-cular adverse events and all-cause mortality were observed more frequently, although not statistically significantly, with risperidone versus placebo.

Effectiveness Data: NIMH CATIE-AD Trial

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Clinical Antipsy-chotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness–Alzheimer’s Disease (CATIE–AD) project compared the effectiveness of antipsychotic medications versus placebo in treating AD-associated psychosis or agitated/aggressive behaviour23. CATIE–AD included outpatients in usual care settings and assessed treatment outcome on several clinical measures over nine months. Initial CATIE–AD treatment (olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone or placebo) was randomized and masked, yet the protocol allowed medication dose adjustments or a switch to a different treatment at any time on the basis of the clinician’s judgement. The primary CATIE–AD phase 1 outcome was time to discontinuation of the initially assigned medication for any reason, which was intended as an overall measure of effective-ness that incorporated the judgements of patients, caregivers and clinicians about therapeutic benefits in relation to undesirable effects.

The two primary hypotheses were that (i) there would be pair-wise differences between the three antipsychotic treatment groups and the placebo group in the time to discontinuation for any reason and (ii) among antipsychotic medications that were different from placebo, none would be inferior to the others. The results revealed no pair-wise treatment differences in all-cause discontinuation. The benefits of olanzapine and risperidone, i.e. longer times to discontinuation for lack of efficacy in comparison to placebo (Kaplan–Meier estimate of median time: olanzapine, 22.1 weeks; quetiapine, 9.1 weeks; risperi-done, 26.7 weeks; placebo, 9.0 weeks), were offset by shorter times to discontinuation due to adverse effects in the antipsychotic groups (discontinuations due to intolerability: olanzapine, 24%; quetiapine, 16%; risperidone, 18%; placebo, 5%)24. The mean last prescribed medication dose was 5.5 mg/day olanzapine, 56.5 mg/day quetiapine and 1.0 mg/day risperidone.

A secondary data analysis of phase 1 in CATIE–AD found that some clinical symptoms improved with atypical antipsychotic medications25. Data from the last phase 1 observation indicated greater improvement with olanzapine or risperidone on NPI total scores and the BPRS hostile suspiciousness factor, as well as for risperidone alone on the BPRS psychosis factor and the CGIC. There was worsening with olanzapine on the BPRS withdrawn depression factor. Among patients continuing phase 1 treatment at 12 weeks, there were no significant differences between antipsychotic medica-tions and placebo on functioning, care needs or quality of life, except for worsened functioning on an activities of daily living (ADL) scale with olanzapine compared to placebo. These results suggest that specific symptoms, rather than global changes, may be more realistic treatment targets for antipsychotic medications when used in dementia and that anger, aggression and paranoia may improve preferentially with treatment. These and other treatment guidelines will be discussed in more detail at the conclusion of the chapter.

Table 53.4 Published randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of atypical antipsychotics for dementia related psychosis or agitation

Analysis of the entire 36-week trial revealed that, metabolically, atypical antipsychotic use was associated with a significant weight gain (0.08 lb/week) and increase in BMI (0.02 kg/m2 per week), with the likelihood of weight gain increasing with longer use of antipsychotic medication26. In sub-group analysis, change in weight reached significance for olanzapine (0.12 lb/week) and quetiapine (0.14 lb/week), but not risperidone (0.10 lb/week); similar findings were present for BMI. When examined by gender, these changes in weight and BMI were significant in women (0.14 lb/week and 0.02 kg/m2 per week, respectively), but not in men (?0.02lb/week and ?0.003 kg/m2, respectively). Further analysis revealed unfavourable overall changes in HDL cholesterol (?0.19mg/dl/wk) and waist circumference (0.07 inches/wk) with olanzapine.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree