Status Epilepticus

A cause of significant morbidity and mortality (

178,

179), status epilepticus requires urgent treatment to avoid neuronal damage and its neurologic consequences (

180,

181). The benzodiazepines have become initial therapy for status epilepticus owing to their rapid onset and proven efficacy (

182), with relatively minor cardiotoxic reactions or respiratory depression compared with barbiturates (

183). In the multicenter, double-blind Veterans Affairs Cooperative Status Epilepticus Trial (

184), patients were randomized to receive lorazepam (0.1 mg/kg), phenytoin (18 mg/kg), phenobarbital (15 mg/kg), or diazepam (0.15 mg/kg) followed by phenytoin (18 mg/kg). Lorazepam was effective in 64.9% of patients, phenobarbital in 58.2%, diazepam/phenytoin in 55.8%, and phenytoin in 43.6% (

p <0.001 lorazepam vs. phenytoin alone). Efficacy appeared to correlate with the rate at which therapeutic drug concentrations were achieved; lorazepam required the shortest time, phenytoin the longest (

p <0.001).

Lorazepam and diazepam were compared for treatment of simple partial, complex partial, and secondarily generalized tonic-clonic status epilepticus in a double-blind study of 78 adults with symptomatic localization-related epilepsy (

182); idiopathic generalized epilepsy with absence status epilepticus was also represented. After the first injection, lorazepam (4 mg) stopped status epilepticus in 78% of patients and diazepam (10 mg) in 58%; effectiveness was 89% and 76% after the second injection (

p = NS between drugs). An open-label, prospective, randomized trial compared lorazepam (0.05 to 0.1 mg/kg) and diazepam (0.3 to 0.4 mg/kg) in children with acute convulsions including convulsive status epilepticus (

185). Lorazepam was statistically more effective (

p <0.01) after the first dose and apparently safer. Its superior efficacy may be the result of a longer duration of action, based on a longer distribution half-life.

Lorazepam may replace diazepam for prehospital treatment of status epilepticus. A large clinical comparison found that status epilepticus had terminated by the time of arrival at the emergency department in 59.1% of patients treated with lorazepam (2 mg), in 42.6% treated with diazepam (5 mg), and in 21.1% given placebo (

186). Rates of circulatory or ventilatory complications were similar (10.6 for lorazepam, 10.3% for diazepam) and lower than those of placebo (22.5%).

Early treatment increases the probability of seizure termination (

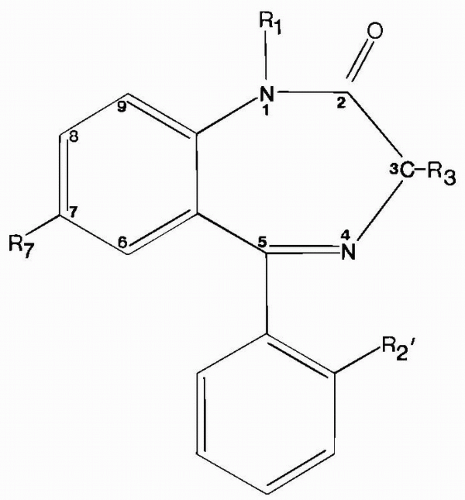

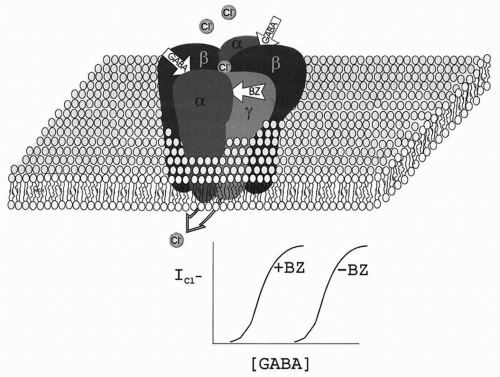

186), most likely because prolonged seizures alter GABA

A receptor susceptibility to benzodiazepines (

187). Reduction in benzodiazepine sensitivity of the GABA

A receptor can occur within minutes in status epilepticus (

188,

189) and may be responsible in part for both the persistent epileptic state and its refractoriness. Refractoriness to diazepam may be mediated by

N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor mechanisms, as NMDA antagonists improve the response to diazepam in late pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus (

190). Moreover, NMDA receptors are upregulated during benzodiazepine tolerance, and NMDA antagonists (e.g., MK801) can block benzodiazepine-withdrawal seizures (

191). These findings suggest a possible strategy for treatment of late benzodiazepine-refractory status epilepticus with combinations of a benzodiazepine (e.g., intravenous midazolam) and an NMDA-receptor antagonist such as the dissociative general anesthetic, ketamine. A recent trial of oral ketamine for refractory nonconvulsive status epilepticus showed efficacy in all five children studied (

192). Such approaches will require validation in controlled clinical trials.

Both lorazepam and diazepam have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of status epilepticus in adults; diazepam has also been approved in children more than 30 days old. Parenteral preparations of midazolam, flunitrazepam, and clonazepam expand the treatment possibilities. Clonazepam for parenteral administration is currently marketed only in Germany and the United Kingdom, and flunitrazepam is not available in the United States. Intramuscular injection and intranasal (

153,

154), buccal (

151), endotracheal (

193,

194), or rectal (

149,

195,

196) instillation also rapidly produce therapeutic levels and are effective against status epilepticus or seizure clusters.

Acute Repetitive Seizures

The need for immediate high drug levels to handle serial seizures is less urgent, and ease of administration by family or allied health workers becomes important. Diazepam rectal gel prevents subsequent seizures during seizure clusters (

195,

196) and can reduce the frequency of emergency department visits (

145).

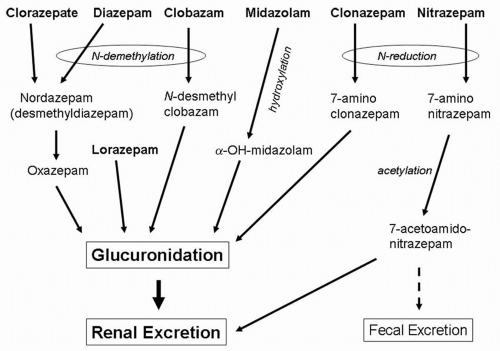

Table 58.2 compares the clinical and pharmacologic properties of the benzodiazepines used for acute seizures. Individual agents can be selected for specific clinical situations. Repeated seizures in a patient rapidly weaned from anticonvulsants for inpatient monitoring could be treated with diazepam (rather than lorazepam), as its shorter peak duration of action may be less likely to suppress seizure activity needed later.

Long-Term Chronic Treatment of Epilepsy

Although their long-term use in epilepsy is limited by sedation and tolerance, benzodiazepines may figure in the adjunctive treatment of myoclonic and other generalized seizure types, or seizures with comorbid anxiety disorders. For example, lorazepam improved control of seizures associated with psychological stressors (

197). The benzodiazepines can be an integral part of a rational polypharmaceutical regimen, defined as the minimum effective AED combination for seizure control.

Intermittent administration when seizure thresholds are transiently reduced may be the ideal strategy for benzodiazepines. Not only are they suited pharmacokinetically for such an application, but such short-term use also may avoid tolerance. For example, catamenial seizures improved with intermittent use of clobazam (

198). Studies

of efficacy for specific indications with the individual agents are discussed below.