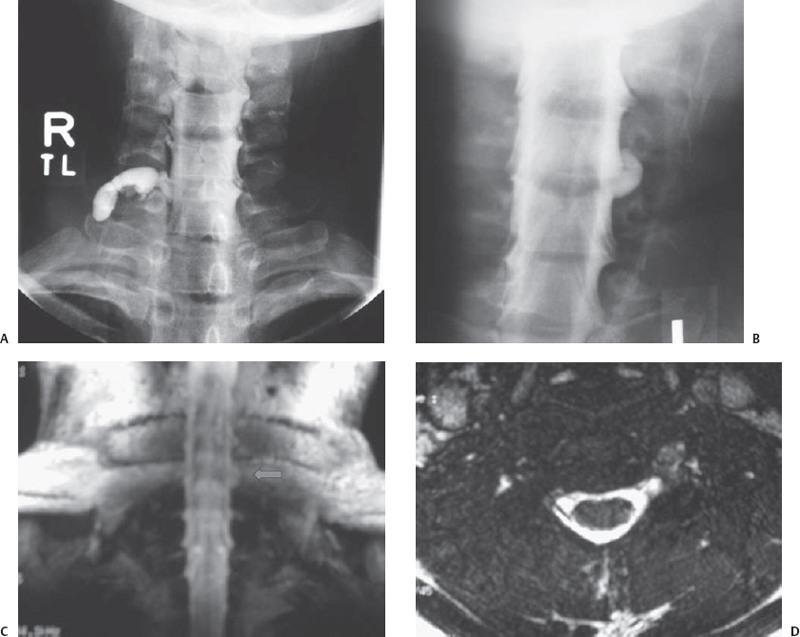

1 Brachial Plexus Avulsion—Diagnostic Issues This 18-year-old male pedestrian was struck by two cars and thrown under one. He held on to an underslung pipe to avoid having his head crushed and was dragged for ˜100 feet. He sustained fractures to the scapula, ribs, clavicle, and skull and developed a subdural hematoma. When he regained consciousness in the intensive care unit he could not move his right arm and could not lift his fingers, cock his wrists, nor flex his elbow. He noted that he could squeeze his fingers slightly. Seven months postinjury he noted no recovery of strength above the elbow. He had no pain in the arm. He denied being short of breath since the injury. Physical examination revealed severe atrophy in the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, deltoid, and biceps. There was good rhomboid function and no winging of the scapula. Sensory exam revealed severely decreased pinprick and light touch over the right deltoid area, and anesthesia of radial forearm down to the thumb, index, and middle finger with hypesthesia of the ring and little fingers. Motor grading showed O/5 for deltoid and supraspinatus, infraspinatus, biceps, brachioradialis, triceps, and supinator. Pronator teres graded 3/5. There was no latissimus dorsi function. The upper and lower part of his pectoralis muscle worked and graded 4/5. There was good hand grip, flexor digitorum profundus (FDP; to all fingers), flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS), and his hand intrinsic muscles graded 5. No triceps or biceps tendon reflex could be elicited. There were no findings of a Horner syndrome. Right upper trunk stretch injury with involvement of the middle trunk A proper and systematic clinical exam is key to find out the involved elements, as is knowledge of the plexus anatomy. Examination starts as usual with inspection and gives the first helpful hints. Typical positioning of the limb can give an impression as to whether involvement of either or both upper and lower plexus elements is predominant (upper plexus: Erb palsy; lower plexus: Klumpke palsy). The shoulders, neck, and upper back should be assessed in the beginning, with the examiner viewing the patient from behind. Asymmetries can be detected such as shoulder drop, scapular rotation, or winging. Latissimus dorsi can be assessed from behind by holding the muscle between the thumb and index finger and asking the patient to cough deeply; if intact, the muscle will contract involuntarily. Deltoid, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, biceps, pectoralis, and hand intrinsic atrophy can usually be assessed by simple visual inspection. It is helpful to examine muscles from proximal to distal and to establish a stereotyped routine that is repeated. Based on a thorough clinical exam it is quite often possible to confine the lesion(s) to a certain level(s). After a complete examination one should be able to decide which roots are involved or if a lesion is more likely to be at truncal or cord level, or which combinations are possible. In this case, root avulsion was a definite possibility and required focusing on findings that might suggest a very proximal lesion and thus possibly an avulsed root. The myotomal patterns can quickly suggest which roots are likely to be involved. The myotomal patterns usually suggest: C5—shoulder abduction, C6—elbow flexion, C7—elbow extension, and C8–T1—hand intrinsic muscles. Beware of C7 because C7 may be avulsed but the triceps still functions due to its C6 and C8 contributions. Examination of the areas of preserved sensation can generate a map, which then can be compared with the arm dermatomes C5 to T1. It should be remembered that the T2 dermatome extends onto the medial underside of the arm and is often larger than textbooks demonstrate when the overlapping C8 and T1 dermatomes are not represented due to root avulsion. The presence of a Horner syndrome or residua of it points toward very proximal T1 damage and is usually an indicator of root avulsion. Sometimes the ptosis resolves, and patients or family members need to be asked if they noticed a drooping eyelid after the accident. In bright light the difference in pupillary size might not be as obvious as expected. The pupils should be assessed in a darkened room, where pupillary differences are more readily appreciated. In general pupillary asymmetry is a more consistent finding than ptosis after injury to the sympathetic ganglion. Phrenic nerve involvement also points to a very proximal level of injury and may be assessed by posterior percussion of the patient’s back in both inspiration and expiration and noting if the level of tympanitic resonance moves inferiorly on inspiration. As the name suggests, deafferentation pain is another indicator of root avulsion. This is especially true in the C8-T1 distribution. Deafferentation pain is central pain and can often be discerned from peripheral pain by the patient’s description of it. Although it certainly may occur with C5, C6, or C7 root avulsions, its manifestations are much less problematic than at the C8 and T1 level, so it is important to inquire about onset of pain and pain characteristics. For further details about pain related to nerve injury, we refer the reader to Chapter 55 of this volume. Right C5, C6 ± C7 root avulsions Right upper and middle trunk stretch injuries A baseline electromyogram (EMG) should be done 3 to 4 weeks after injury, and then the patient is followed for ˜3 to 4 months after injury with periodic clinical and EMG examinations. Electrodiagnostic studies should supplement, not substitute for, a thorough clinical examination. In cases where one can’t be sure if a flicker of movement actually could be palpated, the needle exam can supply confirmation of muscular activity, if done by an experienced electromyographer (sometimes signals obtained might not be from the muscle that was intended to be sampled). For example, the overlying trapezius can be mistaken for the supraspinatus in cases where there is actually total atrophy of the supraspinatus but not of the trapezius. Of all the electrodiagnostic studies EMG is the mainstay for brachial plexus evaluation, especially for follow-up examination. EMG can usually show signs of reinnervation up to a month earlier than the clinical exam. Nerve conduction velocity (NCV) studies play a comparatively minor role for plexus evaluation, with the exception of root avulsion, where they can be very helpful. If there is a good sensory potential despite anesthesia of the supplied dermatome but no motor response from a mixed distal nerve (e.g., ulnar, median) and EMG shows denervation of supplied muscles, this points toward a so-called preganglionic response, which indicates the root is damaged proximal to the dorsal root ganglion. Thus the sensory (not the motor) ganglion is still intact and in continuity with the distal nerve; hence there is peripheral conduction but no central connection (the nerve functions electrically but the patient does not feel anything). The C5 root preganglionic injury cannot be reliably identified with electrodiagnostic testing because its autonomous zone is not easy to stimulate selectively. The main use of radiological studies is to demonstrate root avulsion, which indicates that a root is not a candidate for repair. (There have been recent attempts to reimplant avulsed roots, with encouraging results, but these procedures are experimental.) If there were bony injuries, plain x-rays of the shoulder, neck, clavicle, and arm are required to rule out dislocation and bony fragments. In case of prior surgery one needs to know about the position of plates and screws. A chest x-ray in inspiration and expiration that demonstrates hemidiaphragmatic palsy directly implicates phrenic nerve involvement. Although the capability of MRI myelography to depict brachial plexus elements and pseudomeningoceles has improved tremendously with stronger coils and special sequences, the gold standard in our view is still cervical myelography with good oblique views on the affected side. An important adjuvant is a good postmyelographic thin-slice computed tomographic (CT) scan (1 mm cuts). This study may show rootlet absence without pseudomeningocele formation. A good cervical myelogram can demonstrate pseudomeningoceles nicely. When a pseudomeningocele is seen, it is very likely that the root at the corresponding level was avulsed. However, false-positive results are possible (dural tear without avulsion of all root filaments, partial avulsion). False-negative results are probably more common (root avulsion with no contrast extravasation). A postmyelogram CT scan should always be done because this is more precise and indirectly demonstrates anterior and posterior rootlets. If they are avulsed there is only contrast medium visible, whereas on the contralateral side the normal rootlets are nicely visualized. Even if there is no pseudomeningocele this can be appreciated (Fig. 1–1).

Case Presentation

Case Presentation

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Anatomy

Anatomy

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostic Tests

Electrodiagnostic Studies

Imaging Studies in Brachial Plexus Evaluation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree