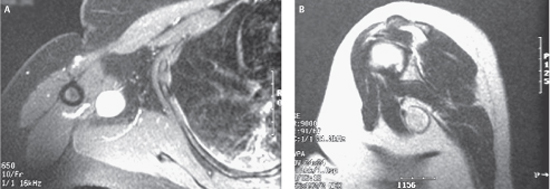

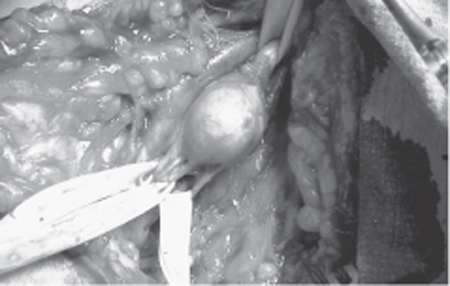

52 Brachial Plexus Tumor A 45-year-old, right-handed woman became aware of a right axillary mass 3 to 4 years ago. When the lesion was palpated, she complained of shooting pain and sometimes paresthetic sensation into the posterior arm and elbow. Over 6 months the mass grew in size. She was investigated with an ultrasound (which showed a 3 cm lesion in the axilla) and negative mammography and was referred to a general surgeon. The latter did a fine needle biopsy of the lesion with inconclusive pathology. Following the biopsy the patient noted worsened dysesthetic pain in the posterior arm. The patient was in good general health, with no systemic features of malignancy. Her past medical and family history was negative for neurofibromatosis (NF) or cancer. Examination revealed a side-to-side mobile mass in the deep right axilla. The patient’s paresthetic symptoms were reproducible by tapping over the mass. No peripheral stigmata of NF were apparent. Her neurological exam was normal. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a well-defined, homogeneously enhancing mass in the right axilla intimately related to the neurovascular structures (Fig. 52–1). Figure 52–1 Magnetic resonance imaging appearance of a nerve tumor in the axilla. (A) T1-weighted axial image with gadolinium shows a brightly enhancing lesion, adjacent and just medial to a vascular structure. (B) The lesion a shows high T2 signal on this sagittal image. The vascular structure lateral to the lesion now appears as a flow void. Figure 52–2 The lesion exposed at surgery via a transaxillary approach was arising from the superficial surface of the proximal radial nerve. The exiting fascicle of origin (middle of the three Penrose drains) was in fact the posterior cutaneous nerve to the arm. Note the axillary vein intimate to but just lateral to the lesion, consistent with the magnetic resonance images. The lesion was exposed through a right transaxillary approach (Fig. 52– 2). Because the lesion was arising from a cutaneous fascicle, the parent radial nerve was readily dissected away and preserved. Gross total resection of the lesion arising from the proximal radial nerve, just distal to the take-off from the posterior trunk of the brachial plexus, was achieved. Pathology confirmed the lesion to be a schwannoma. The patient remains well and deficit-free 3 years postoperatively. Schwannoma of the brachial plexus Five spinal nerves (the anterior rami of C5–8 and T1 nerve roots) contribute to the formation of the brachial plexus in the posterior triangle of the neck. The spinal nerves and trunks (upper, middle, and lower) are located in the supra-clavicular fossa; the divisions are retroclavicular, whereas the cords and the terminal nerves are infraclavicular. Cords (lateral, posterior, and medial) are named in relation to the axillary artery in the axilla at the level of the pectoralis minor muscle. The lateral cord divides into the musculocutaneous nerve and gives a large (mostly sensory) contribution to the median nerve. The median nerve also derives input from the medial cord before the latter then terminates as the ulnar nerve. The posterior cord gives off branches (upper and lower subscapular and thoracodorsal) before terminating as the axillary and radial nerves. In the axilla, the proximal radial nerves starts to branch with a variable number of branches that will innervate the triceps muscle. A sensory branch (posterior cutaneous nerve to the arm) is also given off and runs separately from the main radial nerve trunk as the latter proceeds to the humerus and wraps around the spiral groove from the anterior to posterior arm. Brachial plexus tumors are relatively rare but represent 25% of peripheral nerve tumors. Pain is the commonest presenting symptom in plexal tumors. This holds true for both benign and malignant lesions. Pain can be local or radicular and is typically brought on or aggravated by pressure or tapping on the lesion. A palpable mass is noted by the patient in about half of cases, whereas paresthesias are present in a third of cases. Motor deficit is a late feature and is usually associated with other symptoms; it is more common in malignant lesions. The majority of plexal neurofibromas are associated with NF1 and hence the stigmata of the disease (café au lait spots, cutaneous neurofibromas, axillary freckling) as well as family history should be sought. Classically, there is a palpable mass in the supraclavicular or infraclavicular regions. The mass is firm and has no pulsation. The mass is usually mobile side to side (along the trajectory of the nerve) and not much up and down. With large lesions, mobility is lost because tethering to adjacent structures occurs. This is also the case with malignant lesions that invade surrounding tissues. A Tinel sign is often present on percussion with reproduction of paresthetic symptoms. In advanced cases, sensory loss and weakness or atrophy in muscles innervated by the involved nerve or nerve element may be a clue to the diagnosis and location. In children, axillary lesions are commonly congenital and inflammatory. In adults, inflammatory lesions are more common but neoplastic ones are of increasing propensity. These lesions include enlarged lymph nodes (inflammatory, metastatic), lymphoma, cystic hygroma, lipoma, fibroma, sarcoma, bony tumors, metastasis, vascular lesions, and neural tumors. Nodes involved by regional breast cancer spread are of considerable concern in a women presenting with an axillary mass. The commonest neural lesions involving the brachial plexus are nerve sheath tumors, with schwannoma most frequent, followed by neurofibroma, then malignant neural sheath tumors. The non-neural sheath tumors include benign ones such as desmoid, ganglioneuroma, and cavernous angioma, or malignant ones, including metastasis, Triton tumor, Ewing sarcoma, and osteosarcoma. The plexus may also be involved by regional spread of breast cancer or radiation damage (plexitis) in patients having had prior axillary radiation for cancer. Classification of peripheral nerve tumors is discussed in Chapter 49. Computed tomography and MRI are the main preoperative tests. MRI is far more superior for soft tissue imaging, and all patients should have it before surgery. The MRI allows imaging of all aspects of the brachial plexus, and will assess the spine to seek transforaminal involvement of the spinal nerves and spinal cord. MRI has the capability of delineating the relation of the lesion to the adjoining structures and to the specific elements of the brachial plexus in small lesions as well as the marked tissue invasions by malignant neoplasms. The lesions are usually discrete and isointense on T1-weighted sequence and hypointense to hyperintense on T2-weighted sequence. Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted sequences reveal mostly homogeneous, but at times variable, enhancement (Fig. 52– 1). The natural history of most of the tumors of the brachial plexus is to continue to grow. Hence, the general recommendation is the complete surgical excision of the lesion. In the majority of cases, this is definitive and curative. Small, benign-appearing tumors, especially in a case of NF1, which are asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic should be followed closely and managed conservatively. Very debilitated patients with malignant plexal tumors from underlying terminal neoplasms are also best served with conservative management. The truly plexiform (non-solitary) neurofibromas in patients with NF1 are also generally not operated on, unless there is concern of malignant transformation. Biopsy of the lesion before the definitive surgical procedure is discouraged. Not only is it unnecessary, it is also associated with increased incidences of pain and neurological deficit when compared with nonbiopsied cases. The case presented herein is typical of a neurological deficit incurred by a closed biopsy through a (functioning) fascicle. The surgical resection is usually done by standard anterior supra- and/or infraclavicular approach. This involves full exposure, with isolation and displacement of the intact plexal elements, identification of the involved element, identification (using microscopically assisted intraneural dissection) of the involved and noninvolved fascicles, intraoperative stimulation to determine the functioning fascicles, and finally removal of the tumor with its nonfunctioning fascicles. Occasionally the posterior subscapular approach is performed for lower-element lesions and cases with extensive postsurgical or postradiation scar, which makes a frontal approach difficult or prohibitive. In cases where there is a significant intraspinal component, it is essential to remove it first with laminectomy and fasectomy. In cases of malignant lesions, limb-sparing radical resection by a multidisciplinary team should be done when feasible. This is usually supplemented by adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy, as discussed in Chapter 51. Gross total resection, which is feasible in almost all benign tumors, is associated with a very low recurrence rate. Pain is either improved or unchanged in 80% of cases. Weakness is either improved or unchanged in 50 to 70% of cases. Weakness is less likely to improve compared with pain and could worsen in up to the third of patients with benign lesions (especially ones who have had prior biopsy and thus intraneural scar) and most of the patients with malignant ones.

Case Presentation

Case Presentation

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Anatomy

Anatomy

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Characteristic Clinical Presentation

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostic Tests

Management Options

Management Options

Outcome and Prognosis

Outcome and Prognosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree