Chapter 57 Cardinal Manifestations of Sleep Disorders

Abstract

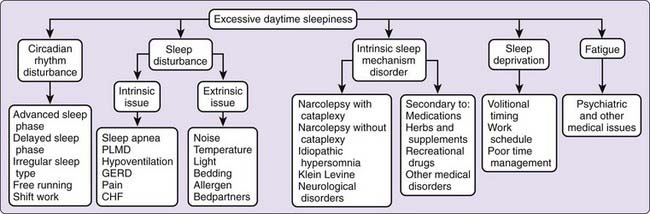

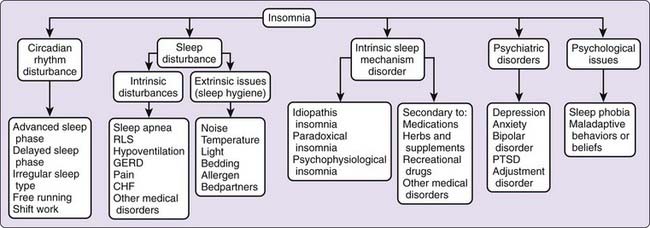

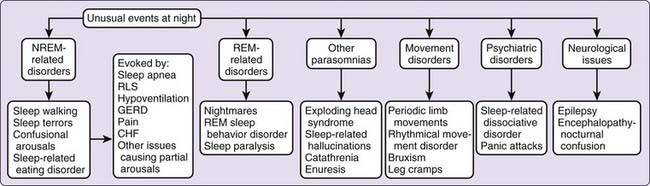

Most patients referred to sleep centers present with one or a combination of three classic complaints: excessive sleepiness, difficulty attaining or sustaining sleep, or unusual events associated with sleep. These symptoms can be easily recognized as related to sleep and are not mutually exclusive. Patients may note more than one problem, such as difficulty sleeping at night and excessive sleepiness during the day. Others may complain of unusual events at night with daytime sleepiness or inability to sleep. Each of these symptoms conveys clues to the underlying pathologic process (Figs. 57-1 to 57-3). In this chapter, we review the cardinal manifestations of sleep disorders and address some of the key features that guide the clinician to pursue further diagnostic evaluations.

Insomnia

Most people have an occasional night fraught with difficulty falling asleep or trouble maintaining sleep. These occasional nights might be closely linked to the surrounding events of the day, psychological challenges, or sudden changes in environment or medical condition. Surveys have shown that approximately 35% of individuals complain that their sleep is disrupted and that a smaller group, of approximately 10%, have a more persistent insomnia.1 For these patients, lack of “good-quality” sleep produces a greater disruption of life and may lead to more significant medical symptoms.

Patients with insomnia frequently give historical clues directed toward the mechanisms behind their insomnia. The symptom complex may indicate an underlying disorder related to primary failure of the sleep mechanics or one in which sleep disruption is the byproduct of another disorder. As sleep is an active process, neuronal networks involved with sleep induction must be engaged and networks involved in wakefulness must be diminished for sleep. Rarely do patients have just one factor responsible for their chronic insomnia. Most patients have factors that put them at risk for development of insomnia, for initiation of the insomnia, and for perpetuation of the insomnia. The presence of predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating factors emphasizes the nature of insomnia as an ongoing process, and clinicians need to search for these contributing factors to outline an effective treatment course (see Chapters 75, Chapter 77, and Chapter 78).

Perception of good sleep is an important factor in evaluating the complaint of insomnia. Some patients exaggerate their symptoms, whereas other patients may not perceive that they are asleep. Paradoxical insomnia is one form of the primary insomnias. Individuals who have this disorder display the normal physiologic parameters of sleep but do not recognize that they have slept. Other patients may endorse unrealistic expectations or unobtainable goals. Patients may assume that sleep should not be interrupted by any arousals or that one must sleep a set number of hours. These beliefs can be easily addressed with education of the patient. Another primary insomnia, idiopathic insomnia, is not associated with clear inciting factors. These individuals usually have lifelong difficulty of sleep and may have significant family history. These primary insomnias are discussed further in Chapters 75 and 77.

The clinician may uncover few physical findings in patients with insomnia. Anxious or hyperalert individuals may demonstrate mild tachycardia, rapid respiratory rate, or cold hands. These individuals may startle easily or be easily distracted during the interview. The clinician should look carefully for signs of obstructive sleep apnea, narrow airway, and obesity because these too can be manifested as insomnia. Signs of Cushing’s syndrome (round face and buffalo hump) or hyperthyroidism (tachycardia and excessive sweating) are important clues to an endocrine disorder. Each patient with insomnia should have a complete neurologic examination to look for potential neurologic lesions impairing sleep. This examination should include an assessment of cognition, mood, and affect. The Mini Mental State Examination is one tool that helps assess cognitive abilities and can be followed over time.2 Clinicians can also use the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory to identify personality and affect issues.

Excessive Daytime Sleepiness

Sleepiness is a common symptom noted by 5% to 20% of individuals.3,4 Most individuals can relate some instances of falling asleep when they intended to be awake. Sleepiness is a normal feeling as one approaches a typical sleep period or after prolonged wakefulness. Excessive sleepiness occurs when one enters sleep at an inappropriate setting or has episodes of unintentional sleep. Excessive sleepiness can occur in degrees. In mild sleepiness, one might fall asleep while reading a book or while sitting quietly. This degree of sleepiness may produce only limited impairment in the person’s perceived quality of life. Greater degrees of sleepiness may be associated with bouts of irresistible sleep or sleep attacks. Irresistible sleep may intrude on such activities as driving, having a conversation, or eating meals. This degree of sleepiness may place the patient at significant risk for accidents and have a major impact on the person’s health and sense of well-being.

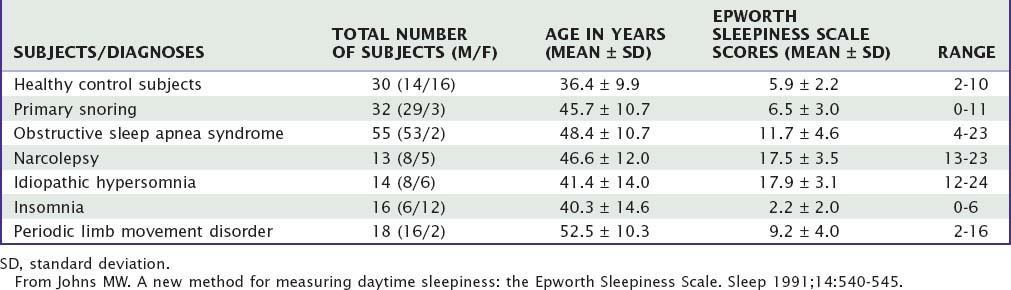

Sleepiness can be quantified subjectively by questionnaires or by physiologic measures such as a multiple sleep latency test. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale is one example of a quantifiable subjective measure of sleepiness and has been translated into several languages (Table 57-1).5 In this scale, the individual is asked to rate on a scale of 0 to 3 (0, no chance; 3, high likelihood) the chance of dozing in a series of eight situations. This score has a modest correlation with physiologic measures of sleep but has a better correlation with the respiratory disturbance index in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (Table 57-2).

Table 57-1 The Epworth Sleepiness Scale

| Name: _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ | |

| Today’s date: ______________________________________________ Your age (years): ______________________________________________ | |

| Your sex (male = M; female = F): _____________________________________________________________________________________________ | |

| How likely are you to doze off or fall asleep in the following situations, in contrast to feeling just tired? This refers to your usual way of life in recent times. Even if you have not done some of these things recently, try to work out how they would have affected you. Use the following scale to choose the most appropriate number for each situation: | |

| SITUATION* | CHANCE OF DOZING |

| Sitting and reading | ________ |

| Watching TV | ________ |

| Sitting, inactive in a public place (e.g., a theater or a meeting) | ________ |

| As a passenger in a car for an hour without a break | ________ |

| Lying down to rest in the afternoon when circumstances permit | ________ |

| Sitting and talking to someone | ________ |

| Sitting quietly after a lunch without alcohol | ________ |

| In a car, while stopped for a few minutes in traffic | ________ |

| Thank you for your cooperation. | |

* The numbers for the eight situations are added together to give a global score between 0 and 24.

From Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep 1991;14:540-545.

Table 57-2 Scores for Various Conditions: Ages and Epworth Sleepiness Scale Scores of Experimental Subjects

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree