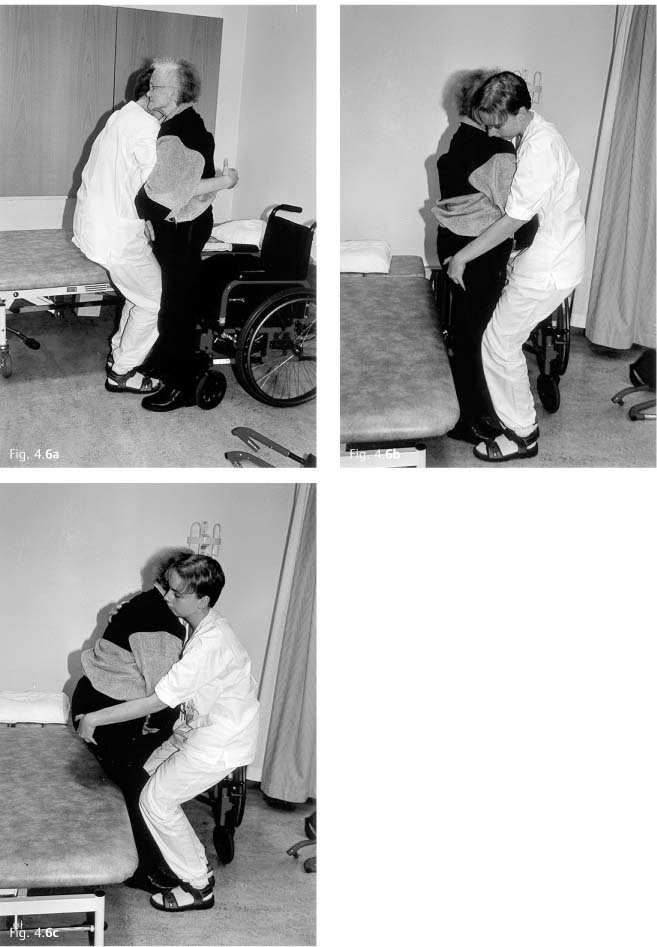

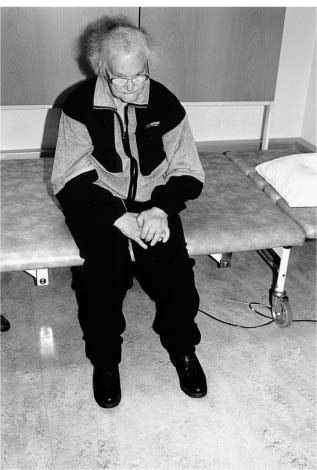

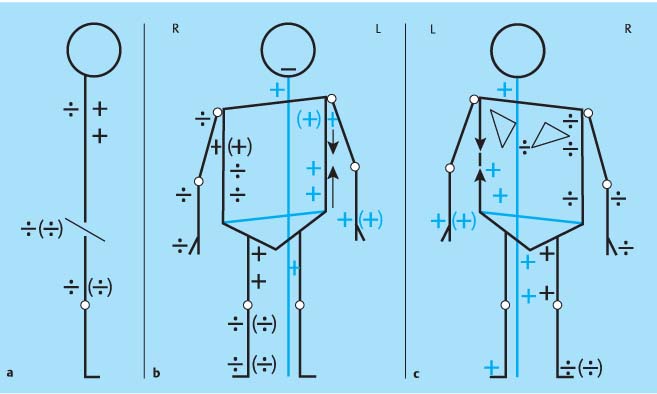

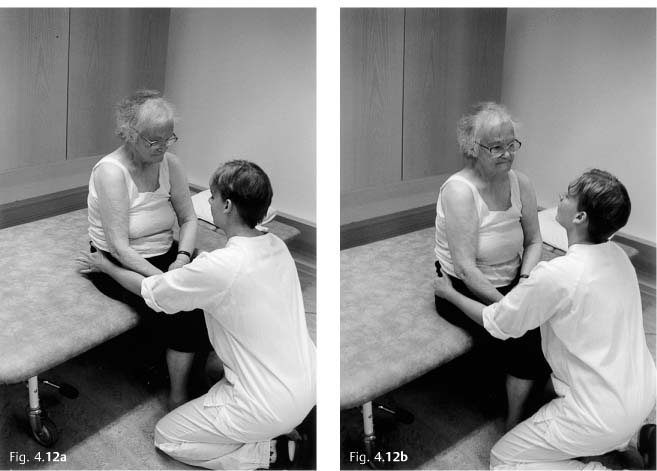

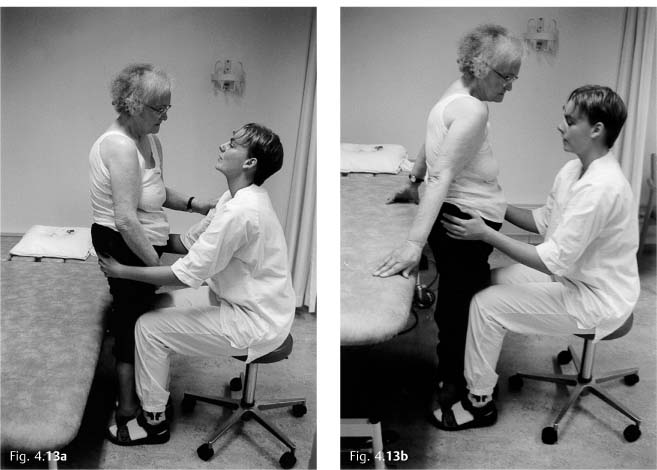

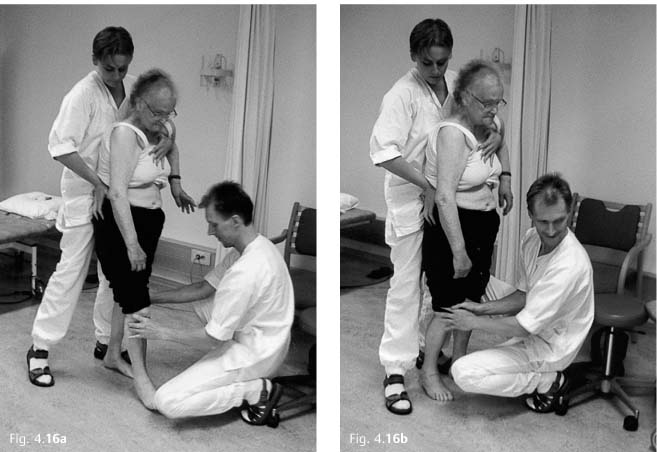

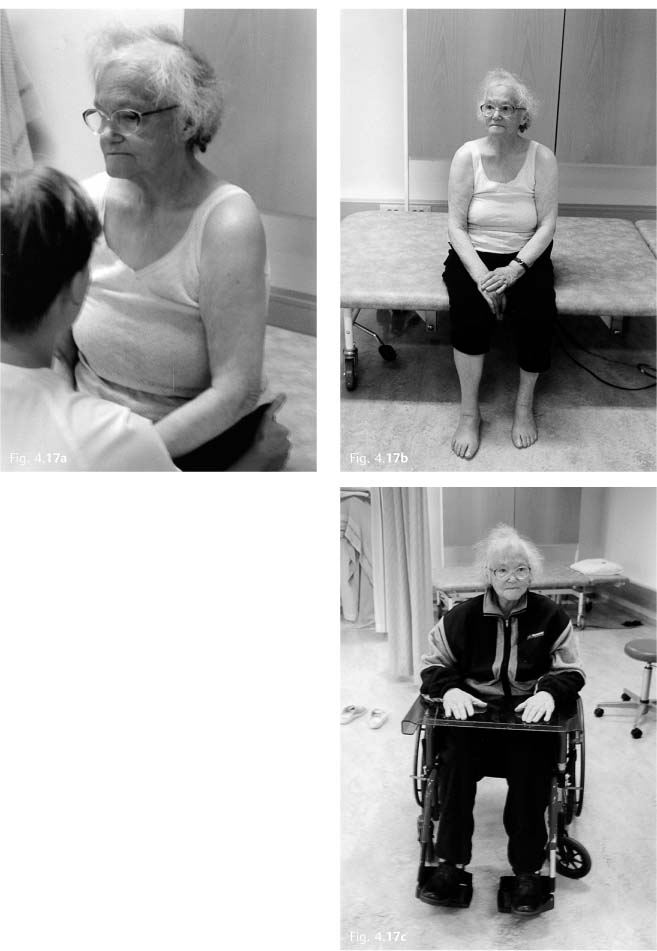

4 Case Histories This chapter presents the case histories of two women, Sissel and Lisa, who represent different diagnostic and age groups. Sissel and Lisa are pseudonyms, but both women gave consent for their pictures to be published in this book. They were treated by colleagues under supervision of the author, later referred to as “I.” The case studies focus on specific issues related to assessment and treatment guided by clinical reasoning. The histories aim to tell two stories with the use of text and pictures and will not make sense unless they are read as a whole. The case studies do not a follow a specific treatment method, but illustrate the use of techniques based on conceptual thinking and clinical reasoning according to the Bobath concept. In this chapter we follow Sissel over a period of 3 months. First we meet her in a stroke unit in ahospital, then in a short-term rehabilitation program in a nursing home before she is discharged and goes home. Chapter 4.2 follows Lisa over two treatment sessions during a 3-week treatment period in a hospital rehabilitation unit. Sissel is an 81-year-old widow. Before she was admitted to hospital with an acute stroke she was fit, healthy, and active. She lived alone in a basement flat prior to her illness. She was self-sufficient and did not need assistance from the local community services. Sissel’s flat is all on one level, but she has to climb a flight of concrete steps to access her flat. Her children are grown up, and a daughter lives in the same neighborhood. Sissel is socially active, has friends, and is a member of a club for the elderly. Most of her friends, however, do not dare to visit her at her home because of the steep flight of stairs. Instead, she is a regular visitor in their homes. Her hobbies are knitting and crocheting—she can knit socks with proper heels and crochet the most delicate tablecloths. One day Sissel was found in her home in a chair unable to move or make herself understood. She was taken to the local emergency department and immediately admitted to the stroke unit. She cannot recall anything about the first few days in hospital. On admission she was aphasic and there was no hyperreflexia and no voluntary activity on the right side except for slight movement in the fingers. A computed tomography scan showed infarction in the frontal lobe on the left side. Sissel was referred for physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy. Sissel’s aim was to return home, preferably to a flat without stairs, and regain her independence. She also wished to be able to continue with her hobbies. Physiotherapy was started 5 days after she was admitted. For ethical reasons, I did not want Sissel to feature in the book until she was medically stable, which was 3 weeks after she was admitted (Fig. 4.1). She understood that this would involve being photographed during therapy for future publication in a book. She was very positive. Fig. 4.1 Sissel 3 weeks after admission to the hospital. Sissel was seated in a wheelchair and was not able to move about herself. She was nursed and needed help in transfers and dressing. She was able to feed herself when food was provided and she was continent, but she needed assistance in the bathroom. She could sit unsupported on a plinth but could not move actively in sitting, nor was she able to right herself. She showed some activity in her right arm; she could move it forward and had some selective finger movements, although none was useful functionally. Sissel could say “yes” and show, by facial expression, whether she meant “yes” or “no.” She had a good understanding of words, but could not find the right ones to use. There did not seem to be any cognitive or perceptual deficits. Observation and handling (Figs. 4.2–4.11). Fig. 4.2 Sissel seated in a wheelchair. Her posture is slightly flexed and displays some overactivity or fixation in her left side, especially in her hand and foot. Her right arm rests in inward rotation, adduction, and flexion on a cushion in her lap. She does not move it actively in this position. The hand is swollen, and the wrist alignment is not clearly defined. On examination the hand is subluxed in a palmar direction in relation to the radius and ulna. Both legs seem slightly internally rotated. Fig. 4.3 The footrests are being removed. Sissel is not able to transfer weight to the left leg when the right leg is lifted. She presses her left arm down on the armrest and clenches her fist. The right leg feels heavy and inactive except for some hold in inward rotation and adduction at the hip. She is not able to take part in the movement. Fig. 4.4 Sissel cannot move forward in the chair. The physiotherapist facilitates her moving forward by a rhythmical weight transfer from hip to hip. There is no spontaneous righting over the pelvis or in the trunk, and she stays flexed in the head, neck, and trunk. She does not respond easily to facilitation and is difficult to move; there is a distinct resistance against weight transfer to the left when her right pelvis and hip is being moved forward in the chair. When the left hip is moved forward she seems to fall to the right. The alignment around the hips and pelvis is then adjusted to prepare for more activity during the next phase of the movement. Fig. 4.5 Sissel cannot stand up unaided. There is a definite push down from her left leg, which forces the pelvis backward and stops her from being able to bring her center of mass over her feet. She therefore needs facilitation and handling for her upper trunk to move forward, achieve a slight anterior pelvic tilt, and thereby some thoracolumbar extension. At this moment she grabs hold of her right hand with the left, probably to include the right arm and shoulder girdle in the movement. This further increases the trunk flexion. Sissel is given some input and support to her right hip and knee because there is no spontaneous recruitment of motor activity in the leg. This preparation allows Sissel to be helped to a standing position. Fig. 4.6a–c There is no activity in Sissel’s right hip and knee in standing, and she needs full support. She pushes with her left leg. She holds on to the therapist with her left shoulder and arm. After a short time in standing she gradually adjusts and becomes more active in extension. The tendency to push with her left leg decreases and she is able to right her trunk more. Weight transference to the left was not possible at this time. Fig. 4.7 Sitting on a plinth. Sissel holds the position through flexor activity of her head and neck, left trunk sideflexion, and flexion of the arms and hips. Hip adductor and inward rotator activity is more easily observed in this position. Sissel needs help to take off her jacket. She is not able to free her arms and falls backward and to the right when she attempts the activity by herself. Fig. 4.8 Sissel is rotated forward and flexed on her left side (observe the clavicle which is more prominent on the left side). Her left arm and leg are active and fix on to her left thigh and push into the floor, respectively. The internal rotation in the right hip is more clearly visible: notice the alignment of the thigh/knee in relation to the floor. Fig. 4.9 Sissel seen from the right side: the tendency to fall to the right and backward is apparent in this figure. Her left foot pushes against the floor and brings her even further back. She attempts to compensate through forward rotation and flexion of her left side together with protraction of her right shoulder girdle and poking her head forward. Sissel’s right arm is actively internally rotating, adducting, and displays increased flexor activity of her shoulder girdle, elbow, wrist, and hand. The right hand seems to press into her thigh. Fig. 4.10 Sissel reaches for her handkerchief with her right hand. She opens her hand and moves her arm forward. Her forward reach is limited by extensor activation at the shoulder joint (possibly the action of proximal triceps, teres major, latissimus dorsi) combined with increased recruitment into elevation, protraction, flexion, and internal rotation of the right shoulder girdle. She does not right herself prior to the movement of the arm—she does not seem to recruit anticipatory postural adjustments. Without this adjustment, she would fall forward if she reached further, which may explain the extensor activation in her right shoulder. Even if Sissel moves her arm forward to some degree, her left trunk and shoulder girdle are still rotated forward in relation to the right side, fixing her position. Fig. 4.11a–c Diagrammatic representation of the assessment. The right side (R) is her most affected side, the left side (L) her less affected side. As the illustration shows, on both sides the tonic relationships and movement strategies are different from what would be expected in a healthy person of the same age and sex. (b) Sissel seen from the front. There is increased activity on her right side in adduction, internal rotation and flexion of both shoulder and hip combined with mild to moderate paresis of extensors and abductors. Her left side displays a level of increased activity in general; a mild to moderate pressure from the shoulder in depression (arrow) at the same time as she pulls her weight on to her left side resulting in what would look like an elevated shoulder. The arrow above her left pelvis illustrates elevation of the pelvis, demonstrating an active shortening of her left side. (c) Sissel seen from behind. The illustration shows the rotatory components of her shoulder girdles, her active left side, and the paresis on her right side as well as increased activation of both hip adductors and medial hamstrings. 1. Sissel displays some voluntary activity in the fingers of her right hand and arm. This indicates that the corticospinal system is partly intact, and the potential for further recovery of selectivity of her right arm and leg should be good. 2. Sissel’s balance is severely affected, but she seems to have intact sensation and vision. She can perceive that she will fall and attempts to regain her balance. This suggests that her basic balance mechanism which is based on visual, vestibular, and somatosensory information, is intact. However, the specific receptors in her skin, muscles, tendons, and joints are not being optimally stimulated due to low tone and reduced motor control on her right side. This will influence the function of the vestibular system indirectly, and may contribute to Sissel’s balance problem. 4. The timing of recruitment for postural control seems to be disturbed: she does not recruit anticipatory postural adjustments as a background for voluntary activation of her arm; she does not right herself for forward reach. 5. The problems in points 2–4 severely affect her postural control, especially her postural stability as a foundation for recruiting activity in relation to opposing gravity, for weight transference and selective function. The interplay between body segments is severely reduced, and therefore also her balance and ability to transfer and move actively and independently. 6. Sissel does not seem to have perceptual or cognitive dysfunction apart from aphasia; she is attentive to herself and her environment, and is motivated for training. When Sissel is assisted to lift her right foot off the footrest, she tries to help (Fig. 4.3); she presses her left arm down on the armrest of her wheel-chair, possibly in an attempt to recruit her left side for contralateral stability in order to free her right leg for movement. This strategy is inappropriate as the fixation through her left side limits weight transference to the left. She is therefore unable to move her right leg freely. Sissel has reduced activation and stability in her right hip and pelvic area. As she attempts to move forward in the chair and transfer her weight to the right to move her left pelvis forward, she almost falls to the right and backward. She compensates by pulling herself further to the left through increasing flexion of her trunk and left arm (Fig. 4.4). As Sissel stands up, she does not initiate righting activity between the body segments (Fig. 4.5). She keeps her hands together, pulls herself up using the therapist and thereby increases her flexor activity generally. Her balance is threatened as the interplay between the proximal and central body segments is reduced together with an inactive right leg. Sissel’s strategy is therefore to fix on to the therapist, pull herself up through flexor activity, and push with her left leg in an attempt to recruit antigravity activity. To stop herself from falling in sitting, Sissel increases the muscular activation throughout her left side to compensate for the instability of her right side (Fig. 4.7–4.10). She displays shortening though flexion on her left side and elongation of her right side, which makes it more difficult for Sissel to activate her right side (biomechanical disadvantage). Lack of anticipatory postural adjustments and sustained flexor activity between the central and the proximal body segments in all planes result in a decreased ability to reach forward for the handkerchief (Fig. 4.11). Sissel’s main problem is reduced postural control through inappropriately timed activation of postural activity, decreased proximal stability, decreased tone and reduced activation of her right side. She therefore increases her activation of her less affected left side to oppose her tendency to fall: she flexes her trunk and sideflexes to the left, fixes with her left arm and pushes with her left leg. This increases the imbalance between her right and left side and causes malalignment in all three planes. As a result, the chances of recruiting activity on her right is increasingly disturbed and causes a further loss of postural control. This causes reduced postural control and trunk interplay. Therefore, the postural background for stability, weight transference, balance, and movement is reduced. On the basis of the above hypothesis, it should not be necessary to specifically train selective motor control of the extremities. Postural control is the basis for voluntary activity and improved postural control in Sissel’s case should allow recovery of the selectivity Sissel already displays (active movement of her right hand and fingers). However, it is necessary to maintain muscle length, alignment and range of movement in both shoulders and hips. As Sissel compensates by activating flexors in these areas, her pectoralis, hip flexors, and adductors are kept in an active, shortened position. If the assumption that the cortico-reticulospinal and cortico-rubrospinal systems are the ones most affected, she may be in danger of developing spasticity and secondary non-neural problems. The shortened muscles will be exposed to these changes the most. If flexors shorten and lose their eccentric ability, other muscle groups (e. g., the extensors) will be biomechanically disadvantaged. As a result, stability, interplay, and weight transference are further compromised. • Participation: Sissel is to return to her own flat or a flat with adaptations. An application for a council flat has been made. • Participation and activity: Sissel shall recover independence; possibly with some help for shopping. • Activity: independent walking ability • Activity: independently perform activities of daily living (ADLs) • Improved postural control (body functions and structures) • Selective and functional extremities (body functions and structures) • Improve alignment in and between body segments, especially head, neck, and trunk (make possible, see Chapter 2): – improve the relationship and adaptation to the base of support – improve thoracic extension and extension, abduction, and outward rotation in shoulder girdles and hips • Facilitate the interplay between body segments based on improved extensor/rotatory control • Facilitate weight transference and stability over left side to free the right side for balance, movement, and transfers • Weight transference in all planes in sitting, standing, and standing to sitting • Explore the recovery of arm function based on improved postural control Sissel received physiotherapy daily, and pictures are taken at intervals of 4–7 days. Therefore, the pictures only give an overview of the physiotherapy Sissel is receiving. Unfortunately the photographs were not standardized, which makes comparison between pictures difficult. However, Sissel’s shoulder girdles are still active in flexion and therefore need to be brought down and back to facilitate stability of the scapulae against the thorax and thereby the interplay between the posterior and anterior trunk musculature for postural activity. By doing this, the interplay between trunk and arm function is facilitated. In this situation, antigravity activity with an emphasis on extension and weight transference through rotation is enhanced. This should facilitate contralateral stability on the left side for activity in the right leg in preparation for stepping. Weight transference is different from weight shift. Weight transference is a dynamic activity whereby the center of gravity is moved to the weightbearing side through stability and interplay. Weight shift is a more passive shift of weight without moving the center of gravity. It may cause strain on joints due to low muscle activation. Weight shift does not activate postural stability, and therefore Sissel would be unable to take over movement control. Walking is an activity, which in its simplest form seems to be driven from the pattern generators at spinal cord level. Independent walking requires postural control, stability, and interaction between body segments. Control of extension and rotation are core elements of this interaction. If pattern generation can be facilitated, it may improve Sissel’s control of balance and movement. The prerequisites for this to happen are optimal alignment, facilitation of the sequence of recruitment of muscle activity, heel-strike, and hip extension. Sissel therefore needs to be facilitated simultaneously in two areas: her trunk to enhance postural stability (rotation and alignment of the trunk in relation to the lower extremities) and her leg for heel-strike, hip extension, and phase shifts from stance to swing. The timing of facilitation between the two facilitating people is a challenge. Fig. 4.12a, b The alignment of the hips in relation to the pelvis is corrected by giving eccentric length to the internal rotators and adductors. Sissel is helped to right her trunk through the therapist’s handling of the pelvis in sitting. Sissel’s hands are in her lap. There are some compensatory activities of the arms into adduction, flexion, and internal rotation of shoulders and arms. This limits her ability to recruit trunk righting. Therefore, another postural set is chosen to develop her extensor activity. Fig. 4.13a, b Standing is a postural set that may enhance postural tone, extension, and postural control, if the alignment allows. Sissel is helped to stand through handling of the pelvis and hips combined with knee support. The shoulder girdles and the arms, the lower arm, and the hand are mobilized and facilitated to allow extension. The alignment improves, and Sissel is able to stabilize her arms on a high support behind. The arms are placed in external rotation to enhance extension of the arms and upper trunk. Fig. 4.14 Sissel attempts to lift her right leg forward by herself. The weight transference to the left is not good enough. There is too much flexion on her left side, which negates the trunk interplay and contralateral stability required for freeing her right leg through selective movement. Fig. 4.15 The alignment is corrected: more extension in her trunk and over the left side to facilitate weight transference through rotation. Sissel still has some flexion in her left side; note the flexion of her left arm in a compensatory attempt to fix. Sissel is not able to recruit appropriate amounts of extension over her right hip and knee, and requires some support. Fig. 4.16a, b Her right leg is facilitated in swing to stance. Sissel’s trunk, pelvis, and hip are brought over her right leg. The hip/pelvis is stabilized and the knee supported without hyper-extension. After a few steps Sissel stands better and more actively, and the activation of her right leg is stronger. Fig. 4.17a–c

4.1 Case History: Sissel

Past Medical History, Social History, Activities, and Participation

History of Present Illness

Assessment

Functional Activity

Language and Cognitive Function

Body Functions and Structures

(a) Sissel seen from her right side; “Q” demonstrates reduced extensor activity and “+” increased flexor activity in her head and neck and upper trunk. She has mild to moderate paresis of her hip and right leg.

Clinical Reasoning and Hypothesis

Systems Control

Compensatory Strategies

Hypothesis

Physiotherapy and Clinical Reasoning

Aims of Therapy

Main Aims

Activity and Body Functions and Structures: Improved Balance

Short-term Goals

Interventions

Body Functions and Structures—Activity

Physiotherapy: Assessment and Treatment as a Continuous Process

First Photo Session (Figs. 4.12–4.17)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree