Central Cord Syndrome: Acute Decompression versus Watch and Wait

Kasra Rowshan

Nitin N. Bhatia

Central cord syndrome (CCS) is an incomplete cervical spinal cord injury, characterized by a greater loss of motor function in the upper extremities as compared to the lower extremities. Complete or near-complete paralysis is often observed in the arms and hands initially, and the ability to ambulate is recovered in majority of cases (1,2). Bladder dysfunction and varying degrees of sensory deficit below the level of injury have also been described (2).

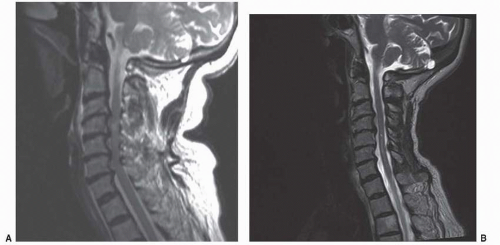

Classically, CCS has been reported in elderly patients with underlying cervical spondylosis who sustain a hyperextension injury (3) (Fig. 141.1). This hyperextension results in posterior pinching of the cord due to infolding of the ligamentum flavum or from anterior compression of the cord by posterior disk-osteophyte complexes. Injury has been attributed to direct necrosis or contusion within the central portion of the spinal cord with stasis of axoplasmic flow, causing edematous injury rather than hematomyelia (4). Gross and histologic examination of postmortem specimens showed no evidence of blood or blood products within the cord parenchyma. Instead, the primary finding was diffuse disruption of axons, especially within the lateral columns of the cervical cord in the region occupied by the corticospinal tract. The central gray matter, however, was intact. Other mechanisms including traumatic fractures, dislocations, and acute disk herniations have also been associated with CCS with similar clinical and pathologic findings.

ANATOMY

When cut transversely, the spinal cord consists of an inner butterfly-shaped gray matter consisting of nerve-cell bodies of efferent and interneural neurons and the surrounding white matter consisting of nerve fibers of either ascending or descending spinal tracts. In humans, the descending motor pathways of the corticospinal tracts pass through the internal capsule and then into the midbrain, while keeping their appropriate somatotopic organization. Caudal to the midbrain, however, their organization is not discrete (5).

The ascending and descending tracts are organized into three regions within the spinal cord: posterior, lateral, and anterior (6). The posterior column is an ascending column of proprioception and vibratory and tactile sensation. Tracts from the lower extremities are placed more medially in the column, and fibers entering the upper extremities are more lateral in the posterior column.

The lateral column contains the lateral corticospinal tract and the lateral spinothalamic tract. The lateral corticospinal tract is a descending pathway for voluntary movement. The lateral spinothalamic tract transmits ascending impulses allowing discrimination of pain and thermal sense from the contralateral side.

The anterior column contains the anterior corticospinal tract and the anterior spinothalamic tract. The anterior corticospinal tract sends descending fibers that control fine movement. The anterior spinothalamic tract sends impulses associated with light touch.

Historically, it has been believed that the corticospinal tract serving the upper extremity is anatomically separate from the ones serving the lower extremities (1, 7, 8 and 9). The fibers that manage movement in the upper extremity are arranged in the medial tract, and the ones that manage movement in the lower extremity are lateral. Some recent studies, however, have suggested that there is a less definite organization (10,11). Tracing studies in monkeys have no differential relationship for the forelimb and the hind limb in the pyramids or cervical spinal cord (5,12).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies have shown similar findings. Quencer et al. (4) found that in both imaging and histologic evaluations of patients with acute CCS, there was no evidence of hematomyelia or injury in the central portion of the spinal cord. Axonal disruption and edema was widespread in the white matter laterally and to a lesser extent in the posterior column.

Levi et al. (11) have provided an alternative explanation for the pattern of neurologic findings observed in acute CCS. They suggested that the corticospinal tract in primates are critical for hand function but not for locomotion. Acute CCS occurs from pathologic injury to the corticospinal tract anywhere from the pyramids to the cervical enlargement.

Generally, causative pathology in patients with acute CCS falls within one of three categories: (a) cervical spondylosis associated with spinal stenosis; (b) traumatic injuries including fractures, dislocations, or subluxations; or (c) acute disk herniation without underlying spinal stenosis (13, 14 and 15).

CLASSIFICATION

A complete neurologic injury refers to total absence of sensory and motor function below the anatomic location in the absence of spinal shock (2,16). In an incomplete injury, residual spinal cord function exists below the anatomical injury site. There are four major patterns to incomplete spinal cord injury, with the most common being CCS.

The second most common is the anterior cord syndrome in which patients present with complete loss of motor function, deep pain, and temperature sensation with preservation of dorsal column function including proprioception, vibration, and light touch. Functional recovery of anterior cord syndrome is usually poor, at 10%.

The extremely rare posterior cord syndrome results in selective injury of the dorsal columns. Patients present with loss of proprioception and light touch with intact motor function. Lastly, Brown-Sequard syndrome is described as ipsilateral loss of motor function, light touch, proprioception, and vibration with a contralateral loss of deep pain and temperature sensation. Functional recovery of Brown-Sequard is the best of these syndromes with a recovery rate of 90%.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

In the general population, traffic accidents account for the majority of cervical traumatic injuries, with sports injuries and assaults also causing high numbers (17,18). In elderly patients, however, ground-level falls, especially down stairs, account for majority of cases. These elderly patients, with their underlying spondylotic stenosis, are at risk of developing CCS.

Physical findings in patients with CCS are normally limited to the neurologic system (2). Classically, patients present with weakness in the upper and lower extremities (7,19). Impairment in the upper extremities is greater than the lower extremities, with significant deficit in the muscles and function of the hands. Loss of sensation, positional and vibratory senses, and reflexes are variable. Sacral sensation is usually normal, as is anal sphincter tone. Bladder dysfunction with urinary retention is the most common neurologic finding.

The incidence of spasticity in CCS is variable. Some report spasticity rates as high as 48% within the first 6 months postinjury (20), and other authors have reported that 20% of their patients had long-term residual spasticity requiring medical management (15). The cause of this long-standing severe spasticity is unknown. Patients that present with lower motor scores on admission, however, tend to develop more spasticity, and it is possible that

these patients sustained a more significant spinal cord injury at the time of the accident. Fortunately, neurologic recovery is not affected by presence or absence of spasticity during the rehabilitation process. Possible negative effects of long-term spasticity on functional outcome include decreased motor control, contractures, impaired coordination, alteration in balance, and ambulation (21), although these effects have not been well categorized in this patient group.

these patients sustained a more significant spinal cord injury at the time of the accident. Fortunately, neurologic recovery is not affected by presence or absence of spasticity during the rehabilitation process. Possible negative effects of long-term spasticity on functional outcome include decreased motor control, contractures, impaired coordination, alteration in balance, and ambulation (21), although these effects have not been well categorized in this patient group.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree