2 Cerebral topography

Surface Features

Lobes

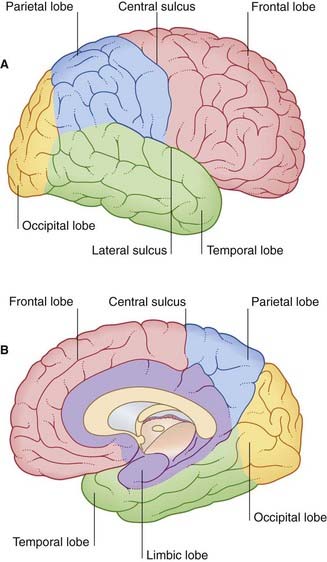

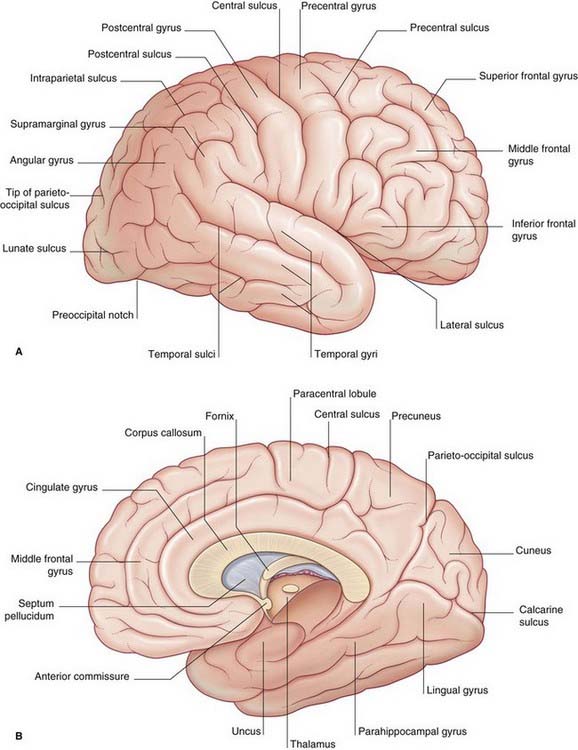

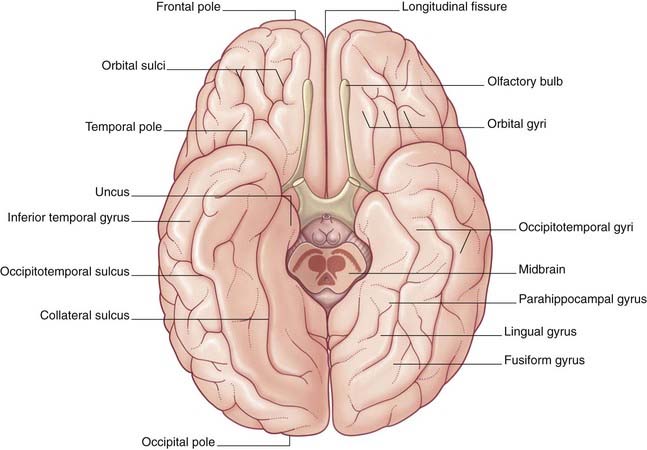

The surfaces of the two cerebral hemispheres are furrowed by sulci, the intervening ridges being called gyri. Most of the cerebral cortex is concealed from view in the walls of the sulci. Although the patterns of the various sulci vary from brain to brain, some are sufficiently constant to serve as descriptive landmarks. Deepest sulci are the lateral sulcus (Sylvian fissure) and the central sulcus (Rolandic fissure) (Figure 2.1A). These two serve to divide the hemisphere (side view) into four lobes, with the aid of two imaginary lines, one extending back from the lateral sulcus, the other reaching from the upper end of the parietooccipital sulcus (Figure 2.1B) to a blunt preoccipital notch at the lower border of the hemisphere (the sulcus and notch are labeled in Figure 2.3). The lobes are called frontal, parietal, occipital, and temporal.

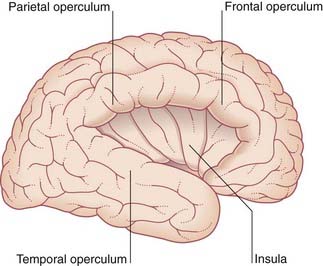

The opercula (lips) of the lateral sulcus can be pulled apart to expose the insula (Figure 2.2). The insula was mentioned in Chapter 1 as being relatively quiescent during prenatal expansion of the telencephalon.

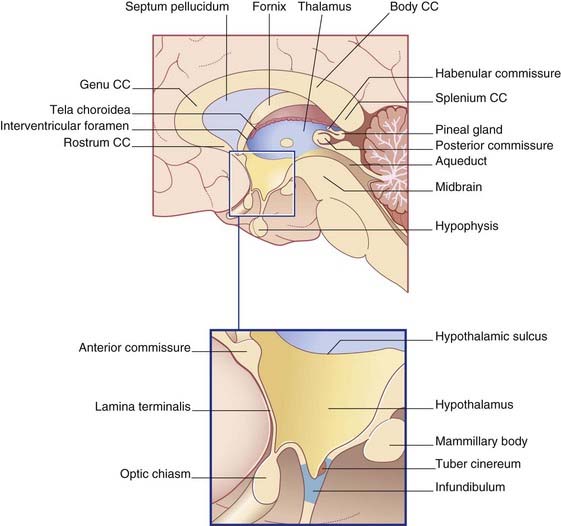

The medial surface of the hemisphere is exposed by cutting the corpus callosum, a massive band of white matter connecting matching areas of the cortex of the two hemispheres. The corpus callosum consists of a main part or trunk, a posterior end or splenium, an anterior end or genu (‘knee’), and a narrow rostrum reaching from the genu to the anterior commissure (Figure 2.3B). The frontal lobe lies anterior to a line drawn from the upper end of the central sulcus to the trunk of the corpus callosum (Figure 2.3B). The parietal lobe lies behind this line, and it is separated from the occipital lobe by the parietooccipital sulcus. The temporal lobe lies in front of a line drawn from the preoccipital notch to the splenium.

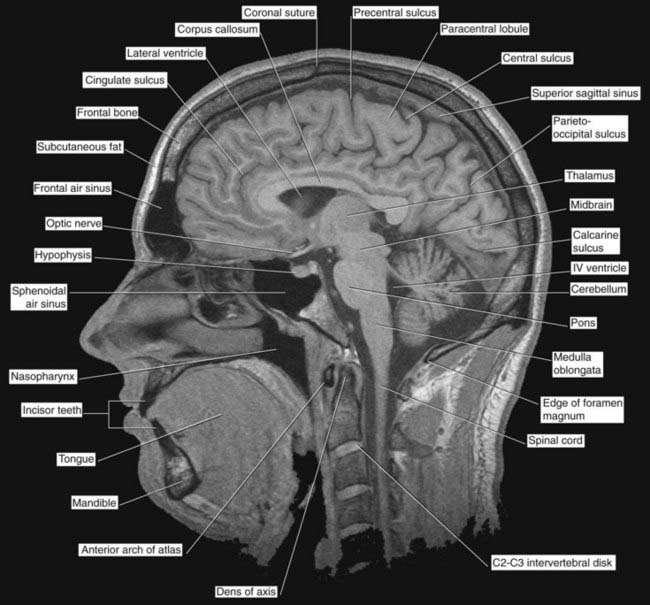

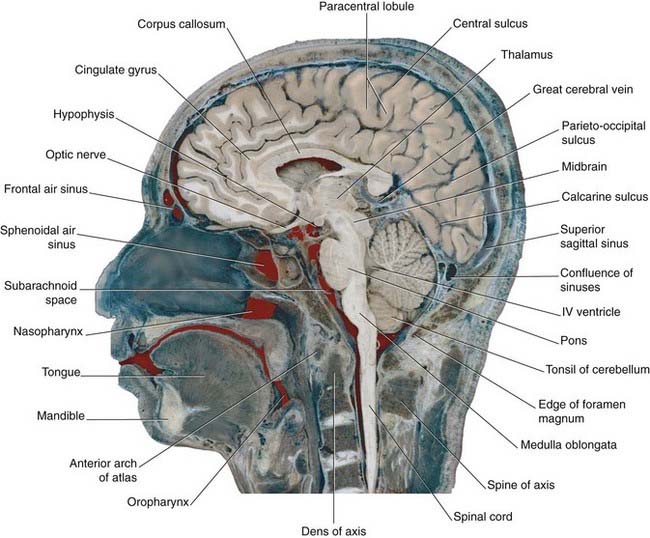

Figures 2.3–2.6 should be consulted along with the following description of surface features of the lobes of the brain.

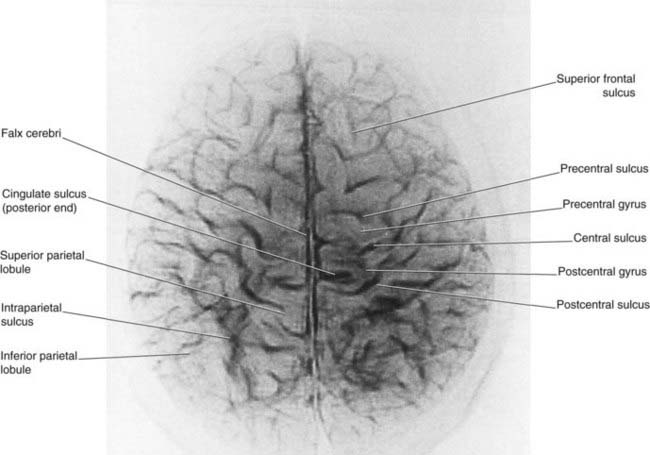

Figure 2.4 ’Thick slice’ surface anatomy brain MRI scan from a healthy volunteer.

(From Katada, 1990.)

Limbic lobe

A fifth, limbic lobe of the brain surrounds the medial margin of the hemisphere. Surface contributors to the limbic lobe include the cingulate and parahippocampal gyri. It is more usual to speak of the limbic system, which includes the hippocampus, fornix, amygdala, and other elements (Ch. 34).

Diencephalon

The largest components of the diencephalon are the thalamus and the hypothalamus (Figures 2.6 and 2.7). These nuclear groups form the side walls of the third ventricle. Between them is a shallow hypothalamic sulcus, which represents the rostral limit of the embryonic sulcus limitans.

Internal Anatomy ofthe Cerebrum

Thalamus, caudate and lentiform nuclei, internal capsule

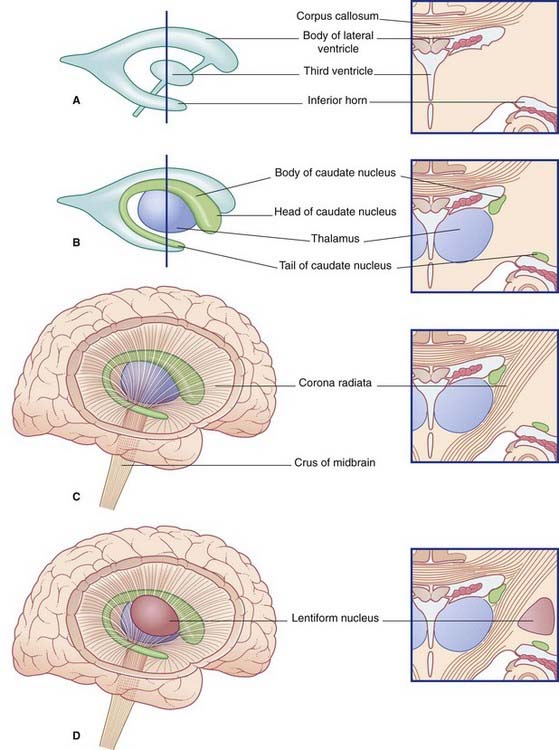

The two thalami face one another across the slot-like third ventricle. More often than not, they kiss, creating an interthalamic adhesion (Figure 2.9). In Figure 2.10, the thalamus and related structures are assembled in a mediolateral sequence. In contact with the upper surface of the thalamus are the head and body of the caudate nucleus. The tail of the caudate nucleus passes forward below the thalamus but not in contact with it.

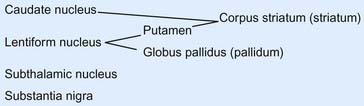

The caudate and lentiform nuclei belong to the basal ganglia, a term originally applied to a half-dozen masses of gray matter located near the base of the hemisphere. In current usage, the term designates four nuclei known to be involved in motor control: the caudate and lentiform nuclei, the subthalamic nucleus in the diencephalon, and the substantia nigra in the midbrain (Figure 2.11).

In horizontal section, the internal capsule has a dog-leg shape (see photograph of a fixed-brain section in Figure 2.12, and the living-brain magnetic resonance image [MRI] ‘slice’ in Figure 2.13). The internal capsule has four named parts in horizontal sections:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree