Cervical Spine Imaging in Trauma

Ishaq Y. Syed

Mir Haroon Ali

Ahmad N. Nassr

Joon Y. Lee

More than 13 million victims of blunt trauma are treated in emergency departments across the United States and Canada annually and are at risk for cervical spine injury (1). Approximately 2% to 3% of these patients suffer from injury to the spinal column, with an increase in the incidence of cervical spinal trauma in those with significant craniofacial trauma (2). Up to half of these injuries are associated with neurologic deficits, with mortality approaching 10% (3). Caring for patients with cervical spine injury is, therefore, a complex interdisciplinary endeavor that requires efficient and accurate clinical and radiographic assessment.

Despite recent efforts to standardize need for radiographic evaluation, protocols remain highly debated and variable across institutions. In this chapter, we review the recent evidence-based literature of imaging modalities as it pertains to evaluating patients with cervical spine trauma.

PLAIN RADIOGRAPHIC EVALUATION

Though the value of plain radiographs has recently been brought to debate, they are often the first imaging modality utilized as an adjunct to the initial evaluation of a trauma patient. An important aspect of the trauma evaluation is to delineate those patients who are at high versus low risk for cervical spine injury. Two large prospective multicenter studies have attempted to clarify the criteria for obtaining radiographs in patients presenting with the possibility of cervical spine injury.

The National Emergency X-Radiography Use Study (NEXUS) (4) conducted a prospective observational study across 21 US institutions to help establish clinical criteria that identify blunt trauma patients requiring radiographic evaluation. They assessed the validity of the decision-making instrument, which consisted of five clinical criteria: the absence of tenderness at the posterior midline of the cervical spine, the absence of a focal neurologic deficit, a normal level of alertness, no evidence of intoxication, and absence of clinically apparent pain that might distract the patient from the pain of a cervical spine injury. Patients who met all five criteria were deemed low risk for cervical spine injury and were not required to have radiographic evaluation. The instrument was used in over 34,000 patients who underwent cervical radiography after blunt trauma. Of these patients, the instrument failed to identify only 8 of 818 patients who had cervical spine injuries (sensitivity of 99.6%, specificity 12.9%), of which two were clinically significant and one went on to surgical treatment. A similarly done Canadian C-Spine Rule study (5) analyzed 8,924 patients and found no abnormal computed tomography (CT) findings in patients thought to be at low risk by a similar set of guidelines (no midline neck tenderness, neurologically intact, ambulatory, able to turn head 45 degrees in both directions, <65 years of age, and low-risk mechanism of injury). With cross-validation, they reported a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 42.5%. These two large prospective studies have become the cornerstone for emergency room trauma spine evaluation and been incorporated into triage trauma protocols at many institutions to determine the need for cervical spine screening imaging.

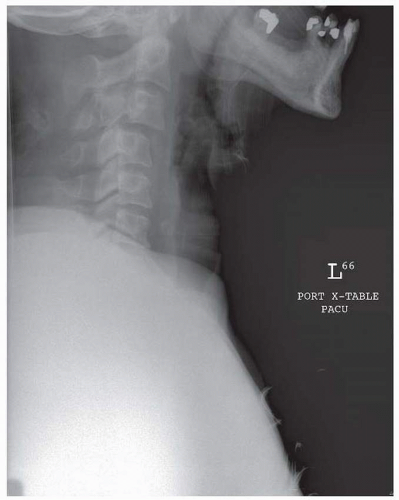

The standard trauma series includes anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and open-mouth views. A lateral cervical radiograph should be evaluated for adequacy, alignment, bony architecture, and soft tissues. Proper radiographic technique is essential. To be deemed adequate, the film should clearly depict the entire cervical spine, extending from the occiput to the upper border of the vertebral body of T1 (Fig. 144.1). There should be no rotation, and the penetrance should reveal bony architecture clearly without losing soft tissue detail. If the cervicothoracic junction is not clearly visualized, supplemental swimmer’s view or supine oblique views may be obtained (6). Approximately 85% of significant injuries to the cervical spine can be detected on a correctly done lateral radiograph (7).

Normal anatomical alignment should be evaluated on the lateral radiograph by assessment of four imaginary anatomic lines: anterior margins of the vertebral bodies, posterior margins of the vertebral bodies, anterior cortical margins of the lamina, and a line formed by the tops of the spinous processes. Each anatomic line should form a smooth contiguous line with an overall lordotic contour. In addition, the lateral radiograph must be carefully evaluated for the vertebral body height, alignment of the facets, interspinous widening, articular pillars, and spinous process fractures (8).

The retropharyngeal soft tissues can be evaluated by measuring the prevertebral space. The measurement

should be less than 10mm at C1, 5 mm at C3, and 15 to 20 mm at C6 (7). The diagnostic value of prevertebral swelling has been shown to be statistically significant in identifying cervical spine injuries (9). This measure may, however, be nonspecific, and the absence of prevertebral hematoma does not necessarily exclude cervical spine injury.

should be less than 10mm at C1, 5 mm at C3, and 15 to 20 mm at C6 (7). The diagnostic value of prevertebral swelling has been shown to be statistically significant in identifying cervical spine injuries (9). This measure may, however, be nonspecific, and the absence of prevertebral hematoma does not necessarily exclude cervical spine injury.

The AP radiograph may be a useful adjunct in providing additional information. The spinous processes are aligned in a vertical row at an approximately equal distance from one another. An interspinous distance of more than 1.5 times the distances above and below may indicate the presence of interlocking articular facets or hyperflexion sprain (10). Open-mouth views may provide information in fractures of the atlas, lateral masses of the axis, or odontoid process. Even with its inherent limitations and lack of detail compared to more advanced imaging modalities, plain radiographs remain an important part of the initial evaluation of cervical spine injuries.

Flexion/extension (F/E) radiographs are often used in a delayed fashion if there remains continued concern for bony or ligamentous injury despite negative standard radiographs. F/E views are most often recommended in alert, neurologically intact patients who have continued pain or tenderness following blunt trauma with an accelerationdeceleration mechanism and can voluntarily perform the study. These patients have potential for ligamentous injury that may otherwise remain undetected on a static neutral view radiograph of the cervical spine (11). The efficacy of F/E views in the acute setting are controversial. Pollack et al. (11) performed a secondary analysis of the NEXUS cohort in order to determine the benefit of ordering F/E views in the acute setting. Of the 818 individuals with radiographic evidence of cervical spine injuries, F/E views were obtained in 86 (10.5%) of injured patients. F/E views alone did not identify any clinically significant or unstable injuries. They concluded that F/E views in the acute setting provided almost no benefit over standard radiographs alone and suggest magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is preferable to F/E when concerned about ligamentous injury and CT in occult fractures. They agreed with recommendations by Wiest and Roth (12) that F/E views should be delayed by 10 to 14 days after the injury to allow muscular spasm from the injury to resolve and that MRI be utilized in the acute setting to evaluate potential ligamentous injuries.

COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY

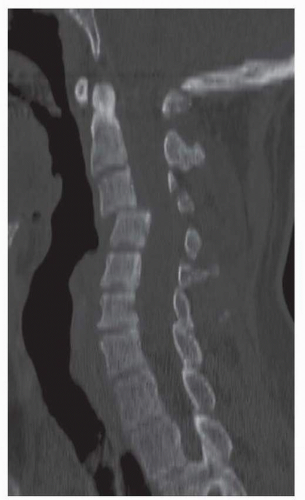

Over the last 15 years, helical CT scanning has replaced traditional cervical spine radiography at most large US trauma centers (13, 14, 15, 16 and 17). Most recently, an update consensus document published by the Eastern Association of the Surgery of Trauma reported plain radiographs having been supplanted by CT as the primary screening modality in patients requiring imaging (18). The helical CT scan is especially useful for closer examination of suspicious or poorly visualized areas such as the upper cervical spine or cervical thoracic junction. Plain radiographs alone may fail to detect cervical spine injuries and accurately depict the full extent of injury (19). CT is indicated in patients with continued symptoms despite negative radiographs, poor visualization of the cervicothoracic junction, and questionable radiographic abnormalities or when plain radiographs depict abnormal prevertebral swelling suggestive of cervical spine trauma. While plain radiographs are still utilized in institutions without readily accessible CT capabilities, plain cervical spine radiography has been largely supplanted by cervical spine CT as the gold standard for initial evaluation of a suspected cervical spine injury. Compared to plain radiography, multidetector CT provides superior evaluation of bony anatomy and detection of pathology (Figs. 144.2, 144.3 and 144.4). Most hemodynamically stable trauma patients are taken directly from the trauma bay to CT for scanning of the head, chest, and abdomen/pelvis. Often, cervical spine images can concurrently be obtained without much additional time or difficulty. If necessary, these images can be reformatted into two- and three-dimensional reconstructions to assist the surgeon in evaluating complex injuries and preoperative planning.

Several studies have shown increased sensitivity and specificity of CT when compared with plain film radiography for detecting injury in the cervical spine (20, 21 and 22). Widder et al. conducted a prospective cohort study evaluating the accuracy of plain radiographs and CT scanning in detecting clinically significant cervical spine injury in obtunded trauma patients. They found that the sensitivity of three-view cervical spine films was 39% versus 100% in CT scanning in detecting cervical spine injury (22). Brohi et al. (23) studied unconscious intubated trauma patients and found CT scanning had a sensitivity of 98.1% with no

missed unstable injuries versus adequate lateral radiographs alone that had a sensitivity of 53.3%. Sanchez et al. prospectively evaluated 2,854 blunt trauma patients utilizing a CT-based protocol in cervical spine clearance. If patients could not be adequately cleared clinically, their entire cervical spine was further evaluated with helical CT scan. They reported a sensitivity of 99% and a specificity of 100% based on this protocol (24). Plain radiographs can be especially difficult to interpret in the upper cervicocranial junction due to soft tissue swelling and obscuring bony details. In patients with substantial head injury, fractures of C1 or occipital condyles can be missed on plain radiographs alone (25). Schenarts et al. prospectively studied consecutive trauma patients who presented with altered mental status. CT scans from occiput to C3 as well as plain cervical spine radiographs were reviewed by two attending radiologists. CT evaluation was found to be superior to plain radiographs in early identification of upper cervical spine injury. Of the 70 cervical spine injuries, plain radiography identified only 55% (38 of 70) compared to 96% (67 of 70) by CT scan. Of the 45% that failed to be identified on plain radiographs, four resulted in motor deficits (26). Barba et al. found in their series that the selective use of helical CT scanning with plain radiographs increased the accuracy of detecting cervical spine injuries from 54% to 100%. They recommend use of CT scan of the entire cervical spine for those blunt trauma patients undergoing head CT scanning (27). The devastating consequences of missing unstable cervical spine fracture has led to routine cervical CT scanning in most trauma centers in the United States.

missed unstable injuries versus adequate lateral radiographs alone that had a sensitivity of 53.3%. Sanchez et al. prospectively evaluated 2,854 blunt trauma patients utilizing a CT-based protocol in cervical spine clearance. If patients could not be adequately cleared clinically, their entire cervical spine was further evaluated with helical CT scan. They reported a sensitivity of 99% and a specificity of 100% based on this protocol (24). Plain radiographs can be especially difficult to interpret in the upper cervicocranial junction due to soft tissue swelling and obscuring bony details. In patients with substantial head injury, fractures of C1 or occipital condyles can be missed on plain radiographs alone (25). Schenarts et al. prospectively studied consecutive trauma patients who presented with altered mental status. CT scans from occiput to C3 as well as plain cervical spine radiographs were reviewed by two attending radiologists. CT evaluation was found to be superior to plain radiographs in early identification of upper cervical spine injury. Of the 70 cervical spine injuries, plain radiography identified only 55% (38 of 70) compared to 96% (67 of 70) by CT scan. Of the 45% that failed to be identified on plain radiographs, four resulted in motor deficits (26). Barba et al. found in their series that the selective use of helical CT scanning with plain radiographs increased the accuracy of detecting cervical spine injuries from 54% to 100%. They recommend use of CT scan of the entire cervical spine for those blunt trauma patients undergoing head CT scanning (27). The devastating consequences of missing unstable cervical spine fracture has led to routine cervical CT scanning in most trauma centers in the United States.

In addition to increased detection of cervical spine injuries, multiple studies have shown cervical spine CT to be more cost-effective than plain film radiography in the trauma setting (14,20). These studies analyzed cost estimates for time on the scanner, technologist’s time, cost of materials, and the potential cost of missed unstable injuries and preventable paralysis (including prolonged hospitalizations, rehabilitation, lost productivity, and malpractice suits). Daffner and colleagues reported on 156 trauma patients and demonstrated that an adequate CT scan of the cervical spine could be obtained with an average additional time of 12 minutes to the patient’s overall radiologic trauma evaluation. This was approximately half the time required to perform a complete six-view traditional radiographic evaluation (28). Antevil et al. studied the effects of their institutional transition from plain radiographs to spiral CT in the initial radiographic evaluation of trauma patients. The sensitivity of detecting spine fractures in the x-ray group was 70% versus 100% in the CT group. The mean time in radiology was also decreased in the CT group (1 hour vs. 1.9 hours, p< 0.001), and the mean overall cost of spinal imaging per patient was similar (172 dollars vs. 164 dollars). In cervical spine imaging, the overall radiation exposure was higher (13 mSv vs. 26 mSv) with the use of CT (29). The authors concluded that spiral CT provided for a more rapid and sensitive imaging modality with similar cost in the initial evaluation of spine trauma patients and may become the standard of care. If the rate of missed fractures is incorporated into the analysis, the helical CT has been shown to be more cost-effective in the long run (30). The main disadvantages of CT include increased radiation exposure and more limited availability compared to plain radiography. CT provides a rapid and sensitive imaging modality with similar cost in the initial evaluation of spine trauma patients and is becoming the standard of care (29). There has been a recent trend toward utilizing helical CT alone as the primary screening tool in high-risk trauma patients (27).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree