Cervical Spine Osteotomy in Ankylosing Spondylitis

Edward Donald Simmons

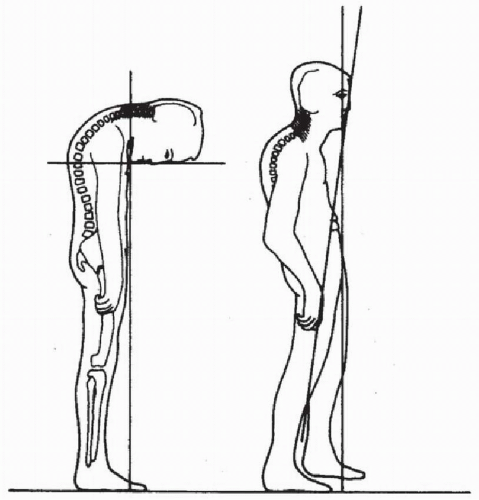

Ankylosing spondylitis is a seronegative inflammatory arthritis of the spine that results in ossification and rigidity, but usually not deformity that is significant enough to warrant any surgical correction; however, there are instances where flexion deformity will arise that can warrant surgical intervention (Fig. 131.1). The most severe deformities of the cervical spine are often those that follow a relatively trivial traumatic incident, which results in a transversely oriented fracture (1). These often go undiagnosed or treated minimally such as with a soft collar and often result in the neck gradually flexing forward over the ensuing weeks and months into a more fixed position in flexion. In the most severe cases, this can result in a true “chin-onchest” type of deformity. In these types of cases, patients will have difficulty with hygiene of the skin between the chin and chest as well as difficulty with their visual field being able to see ahead and, occasionally, even difficulties with swallowing. In these most severe deformities, surgical correction can be a treatment option that will improve the patient’s quality of life and functional status (Fig. 131.2). Milder flexion deformities of less than 30 degrees usually do not warrant surgical intervention.

If a patient with known ankylosing spondylitis presents to an emergency room or clinic following a minor traumatic episode such as a “fender bender” automobile accident, he must be assumed to have a possible cervical fracture until this is conclusively ruled out with computed tomography (CT) scan (Fig. 131.3). Plain radiographs are notoriously unreliable in ruling out this type of fracture, which can be undetected (1, 2 and 3). If a fracture is diagnosed, then immobilization of the neck with a halo vest is appropriate, and no surgery is needed as these fractures have a high incidence of successful healing without operative management. If there has been some displacement or if there is any deformity that has occurred, then gentle inline traction with the neck put into the “preinjury” alignment should be carried out. Using traction to carry out correction of the neck beyond where its position was before the injury is not advisable as this can result in some displacement and neurologic impingement. If the fracture is deemed unstable, even with halo vest immobilization, operative stabilization can be carried out via a dorsal fixation and fusion.

Major flexion deformities present many functional handicaps to an individual. In addition to those noted above, patients will have difficulty climbing or descending stairs and being able to safely cross streets and navigate through normal daily outdoor activities and would typically preclude driving an automobile.

In preoperative planning, the overall health assessment of the patient must be taken into account. The bone quality, the volume of the spinal canal as assessed with CT scan imaging, and any potential vertebral artery anomalies should be evaluated. The osteotomy should be carried out at the C7-T1 level as this is safely below the entry of the vertebral arteries, and the spinal canal at C7-T1 is general fairly spacious. Carrying out the osteotomy below T1 will not result in any correction due to the rib cage (4). The surgery is done with the patient in the sitting position using a specialized type of dental chair. The patient is fitted with a halo vest before the surgery is done, and the surgery is carried out using intravenous sedation along with local anesthesia (5). Positioning the patient in the prone position is not recommended, particularly in the more severe flexion deformities as the positioning is extremely difficult and risky. Displacement of the osteotomy could actually occur before the surgeon is ready. Also it is quite difficult to operate from a technical standpoint with the patient’s head in a downward direction, and the control of the head-neck situation with the patient in the sitting position is much more easily attained.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Procedure: The patient is prefitted with a halo in the operating room and then positioned in a specialized dental-type chair. Gentle inline traction with 5 pounds is applied to an overhead support (6). The dorsal neck is shaved, prepped, and draped with a translucent stick-on plastic drape as shown in Figure 131.4. The patient is also fitted with a Doppler monitor on the chest to detect any air embolisms, which is one of the potential risks of performing surgery in the sitting position (6). To date, the author has not had any major complications due to an air embolism. A sponge immersed in saline is always

kept available to be placed in the wound should any air embolism be detected on the Doppler imaging.

kept available to be placed in the wound should any air embolism be detected on the Doppler imaging.

A midline incision is made, and local infiltration of 1% lidocaine is used in the skin and subcutaneous tissues down to the deep fascial tissue and ligamentum nuchae before making the skin incision. Once the tips of the spinous processes have been identified, further infiltration with 1% lidocaine is used in the deep fascial periosteal plane along the dorsal aspects of the laminae and tips of the spinous processes. Subperiosteal dissection and elevation of the paraspinal muscle mass can then be carried out. This is surprisingly well tolerated by most patients. If some pain is produced during the procedure, further infiltration is used and the procedure can be continued. It is paramount to keep the patient as comfortable as possible, and some intravenous sedation also helps in regard

to this. Once the spine has been exposed, the correct levels must be ascertained. The facet capsule tissue is completely cleared away on both sides.

to this. Once the spine has been exposed, the correct levels must be ascertained. The facet capsule tissue is completely cleared away on both sides.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree