The Acquired Metabolic Disorders of the Nervous System: Introduction

An important segment of neurologic medicine, and one that is seen with great frequency in general hospitals, are disorders in which a global disturbance of cerebral function (encephalopathy) results from failure of some other organ system—heart and circulation, lungs and respiration, kidneys, liver, pancreas, and the endocrine glands. Unlike the diseases considered in Chap. 37, in which a genetic abnormality affects the metabolic functions of many organs and tissues including the brain, the cerebral disorders discussed in this chapter are strictly secondary to derangements of the visceral organs themselves. They stand at the interface of internal medicine and neurology.

Relationships of this type, between an acquired disease of some thoracic, abdominal, or endocrine organ and the brain, have rather interesting implications. In the first place, recognition of the neurologic syndrome may be a guide to the diagnosis of the systemic disease; indeed, the neurologic symptoms may be more informative and significant than the symptoms referable to the organ primarily involved. Moreover, these encephalopathies are often reversible if the systemic dysfunction is brought under control. Neurologists must therefore have an understanding of the underlying medical disorder, for this may provide the means of controlling the neurologic part of the disease. In other words, the therapy for what appears to be a nervous system disease lies squarely in the field of internal medicine—a clear reason why every neurologist should be well trained in internal medicine. Of more theoretical importance, the investigation of the acquired metabolic diseases provides new insights into the chemistry and pathology of the brain. Each visceral disease affects the brain in a somewhat different way and, because the pathogenic mechanism is not completely understood in any of them, the study of these metabolic diseases promises rich rewards to the scientist.

Table 40-1 lists the main acquired metabolic diseases of the nervous system according to their most common modes of clinical expression. Not included are the diseases caused by nutritional deficiencies and those caused by exogenous drugs and toxins, which can be considered metabolic in the broad sense; these are discussed in the following chapters.

|

Diseases Presenting as Confusion, Stupor, or Coma (Metabolic Encephalopathy)

The syndrome of impaired consciousness, its general features, the terms used to describe it, and the mechanisms involved are discussed in Chap. 17. There it was pointed out that metabolic disturbances are frequent causes of impaired consciousness and that their presence must always be considered when there are no focal signs of cerebral disease and both the imaging studies and the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) are normal.

Intoxication with alcohol and other drugs figures prominently in the differential diagnosis. The main features of the reversible metabolic encephalopathies are confusion, typified by disorientation and inattentiveness and accompanied in certain special instances by asterixis, tremor, and myoclonus, usually without signs of focal cerebral disease. This state may progress in stages to one of stupor and coma. Slowing of the background rhythms in the electroencephalogram (EEG) reflects the severity of the metabolic disturbance. With few exceptions, usually pertaining to cerebral edema and certain cases of hepatic encephalopathy, imaging studies are normal. Seizures may or may not occur, most being associated with particular underlying causes of encephalopathy such as hyponatremia and hyperosmolarity.

Laboratory examinations are highly informative in the investigation of the acquired metabolic diseases. In patients with symptoms suggestive of a metabolic encephalopathy the following determinations are usually made: serum Na, K, Cl, Ca, Mg, glucose, HCO3, renal function tests (blood urea nitrogen [BUN] and creatinine), liver function tests (aspartate aminotransferase [AST], alanine aminotransferase [ALT], bilirubin, NH3), thyroid function tests (T4 and thyroid-stimulating hormone [TSH]), and osmolality and, in certain cases, oxygen saturation and blood gas determinations. These are almost always supplemented by toxicology tests and measurement of the serum concentrations of relevant medications as discussed in the next chapter. Serum osmolality can be measured directly or calculated from the values of Na, glucose, and BUN (in mg/dL), using the following formula:

Normal serum osmolality is 270 to 290 mOsm/L. When there is a discrepancy of greater than 10 mOsm/L between the calculated and the directly measured values (osmolal, or osmolar gap), it can be assumed that additional circulating ions are present. Most often they are derived from an exogenous toxin or drug such as mannitol, but renal failure, ketonemia, or an increase of serum lactate may result in the accumulation of small molecules that contribute to the measured serum osmolality.

A point to be remembered is that the brain may be damaged, even to an irreparable degree, by a disturbance of blood chemistry (e.g., hypoglycemia, hypoxia) that has vanished by the time the patient is examined.

Here the basic disorder is a lack of oxygen and of blood flow to the brain, the result of failure of the heart and circulation or of the lungs and respiration. Often, both are responsible and one cannot say which predominates; hence the dually ambiguous allusions in medical records to “ischemic-hypoxic” encephalopathy. This combined encephalopathy in various forms and degrees of severity is one of the most frequent and disastrous cerebral disorders encountered in every general hospital.

Reduced to the simplest formulation, a deficient supply of oxygen to the brain is either the result of a failure of cerebral perfusion (ischemia) or of a reduced amount of circulating arterial oxygen, of diminished oxygen saturation, or of insufficiency of hemoglobin (hypoxia). Although they are often combined, the neurologic effects of ischemia and hypoxia are subtly different. The medical conditions that most often lead to it are as follows:

A global reduction in cerebral blood flow (myocardial infarction, ventricular arrhythmia, aortic dissection, external or internal blood loss, and septic or traumatic shock)

Hypoxia from suffocation (drowning, strangulation, or aspiration of vomitus, food, or blood; from compression of the trachea by a mass or hemorrhage; tracheal obstruction by a foreign body, or a general anesthesia accident)

As a subset of the above, diseases that paralyze the respiratory muscles (Guillain-Barré syndrome, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, myasthenia, and, in the past, poliomyelitis) or damages the medulla and leads to failure of breathing

The special case of carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning (nonischemic hypoxia)

The product of blood oxygen content and the cardiac output is the ultimate determinant of the adequacy of oxygen supply to the organs. When blood flow is stable, the most important element in the delivery of oxygen is the oxygen content of the blood. This is the product of hemoglobin concentration and the percentage of oxygen saturation of the hemoglobin molecule. At normal temperature and pH, hemoglobin is 90 percent saturated at an oxygen partial pressure of 60 mm Hg and still 75 percent saturated at 40 mm Hg; i.e., as is well known, the oxygen saturation curve is not linear.

A number of physiologic mechanisms of a homeostatic nature protect the brain under conditions of both ischemia and hypoxia. Through a mechanism termed autoregulation, there is a compensatory dilatation of resistance vessels in response to a reduction in cerebral perfusion, which maintains blood flow at a constant rate, as noted in Chap. 34. When the cerebral blood pressure falls below 60 to 70 mm Hg, an additional compensation in the form of increased oxygen extraction allows normal energy metabolism to continue. In total cerebral ischemia, the tissue is depleted of its sources of energy in about 5 min, although longer periods are tolerated under conditions of hypothermia. Also, energy failure because of hypoxia is counteracted by an autoregulatory increase in cerebral blood flow; at a PO2 of 25 mm Hg, the increase in blood flow is approximately 400 percent. A similar increase in flow occurs with a decrease in hemoglobin to 20 percent of normal.

In most clinical situations in which the brain is deprived of adequate oxygen, as already commented, there is a combination of ischemia and hypoxia, with one or the other predominating. The pathologic effects of ischemic brain injury from systemic hypotension differ from those caused by pure anoxia. Under conditions of transient ischemia, one pattern of damage takes the form of incomplete infarctions in the border zones between major cerebral arteries (Chap. 34). With predominant anoxia, neurons in portions of the hippocampus and the deep folia of the cerebellum are particularly vulnerable. More severe degrees of either ischemia or hypoxia, or the combination, lead to selective damage to certain layers of cortical neurons, and if more profound, to generalized damage of all the cerebral cortex, deep nuclei, and cerebellum. The nuclear structures of the brainstem and spinal cord are relatively resistant to anoxia and hypotension and stop functioning only after the cortex has been badly damaged.

The cellular pathophysiology of neuronal damage under conditions of ischemia is discussed in Chap. 34. One mechanism of injury is an arrest of the aerobic metabolic processes necessary to sustain the Krebs (tricarboxylic acid) cycle and the electron transport system. Neurons, if completely deprived of their source of energy, are unable to maintain their integrity and undergo necrosis. However, neuronal cell death occurs through more than one mechanism. The most acute forms of cell death are characterized by massive swelling and necrosis of neuronal and nonneuronal cells (cytotoxic edema). Short of immediate ischemic necrosis, a series of internally programmed cellular events may also propel the cell toward death in a delayed fashion, a process for which the term apoptosis has been borrowed from embryology. There is experimental evidence that certain excitatory neurotransmitters, particularly glutamate, contribute to the rapid destruction of neurons under conditions of anoxia and ischemia (Choi and Rothman); the pertinence of these effects to clinical situations is uncertain. Ultimately, this process may be affected by massive calcium influx through a number of different membrane channels, which activates various kinases that participate in the process of gradual cellular destruction. Free radical generation appears to play a role in membrane dissolution as a result of these processes. As shown in experimental models, one of the reasons for the irreversibility of ischemic lesions may be swelling of the endothelium and blockage of circulation into the ischemic cerebral tissues, the “no-reflow” phenomenon described by Ames and colleagues. There is also a poorly understood phenomenon of delayed neurologic deterioration after anoxia; this may be a result of the blockage or exhaustion of some enzymatic process during the period when brain metabolism is restored.

Mild degrees of hypoxia without loss of consciousness induce only inattentiveness, poor judgment, and incoordination; in our experience, there have been no lasting clinical effects in such cases, although Hornbein and colleagues found a slight decline in visual and verbal long-term memory and mild aphasic errors in Himalayan mountaineers who had earlier ascended to altitudes of 18,000 to 29,000 ft. These observations make the point that profound anoxia may be well tolerated if arrived at gradually. For example, we have seen several patients with advanced pulmonary disease who were fully awake when their arterial oxygen pressure was in the range of 30 mm Hg. This level, if it occurs abruptly, causes coma. An important derivative observation is that degrees of hypoxia that at no time abolish consciousness rarely, if ever, cause permanent damage to the nervous system.

In the circumstances of severe global ischemia with prolonged loss of consciousness, the clinical effects can be quite variable. Following cardiac arrest, for example, consciousness is lost within seconds but recovery can be complete if breathing, oxygenation, and cardiac action are restored within 3 to 5 min. Beyond 5 min there is usually permanent injury. Clinically, however, it is often difficult to judge the precise degree and duration of ischemia, because slight heart action or an imperceptible blood pressure may have served to maintain the circulation to some extent. Hence some individuals have made an excellent recovery after cerebral ischemia that apparently lasted 8 to 10 min or longer. Subnormal body temperatures, as might occur when the body is immersed in ice-cold water, greatly prolong the tolerable period of hypoxia. This has led to the successful application of moderate cooling after cardiac arrest as a technique to limit cerebral damage (see further on in Treatment of Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy section).

Generally speaking, anoxic patients who demonstrate intact brainstem function as indicated by normal pupillary light and ciliospinal responses, induced by passive head turning (doll’s eye movements), and other vestibulo-ocular reflexes have a more favorable outlook for recovery of consciousness and perhaps of all mental faculties. Conversely, the absence of these brainstem reflexes even after circulation and oxygenation have been restored, particularly pupils that fail to react to light, implies a grave outlook as elaborated further on. If the damage is almost total, coma persists, decerebrate postures may be present spontaneously or in response to painful stimuli, and bilateral Babinski signs can be evoked. In the first 24 to 48 h, death may terminate this state in a setting of rising temperature, deepening coma, and circulatory collapse, or the syndrome of brain death intervenes, as discussed below.

Most patients who have suffered severe but lesser degrees of hypoxia will have stabilized their breathing and cardiac activity by the time they are first examined; yet they are comatose, with the eyes slightly divergent and motionless but with reactive pupils, the limbs inert and flaccid or intensely rigid, and the tendon reflexes diminished. Within a few minutes after cardiac action and breathing have been restored, generalized convulsions and isolated or grouped myoclonic twitches may occur. Either of these phenomena are poor prognostic signs. With severe degrees of injury, the cerebral and cerebellar cortices and parts of the thalami are partly or completely destroyed but the brainstem-spinal structures survive. Tragically, the individual may survive for an indefinite period in a state that is variously referred to as cortical death, irreversible coma, or persistent vegetative state (see discussion of these subjects in Chap. 17). Some patients remain mute, unresponsive, and unaware of their environment for weeks, months, or years. Long survival is usually attended by some degree of improvement but the patient appears to know nothing of his present situation and to have lost all past memories, cognitive function, and capacity for meaningful social interaction and independent existence (a minimally conscious state, actually a severe dementia; see Chap. 17). One has only to observe such patients and their families to appreciate the gravity of the problem, the family’s anguish, and the tremendous expense of medical care. The only person who does not appear to suffer is the patient.

With lesser degrees of anoxic-ischemic injury, the patient improves after a period of coma lasting hours or less. Some of these patients quickly pass through this acute post-hypoxic phase and proceed to make a full recovery; others are left with varying degrees of permanent disability.

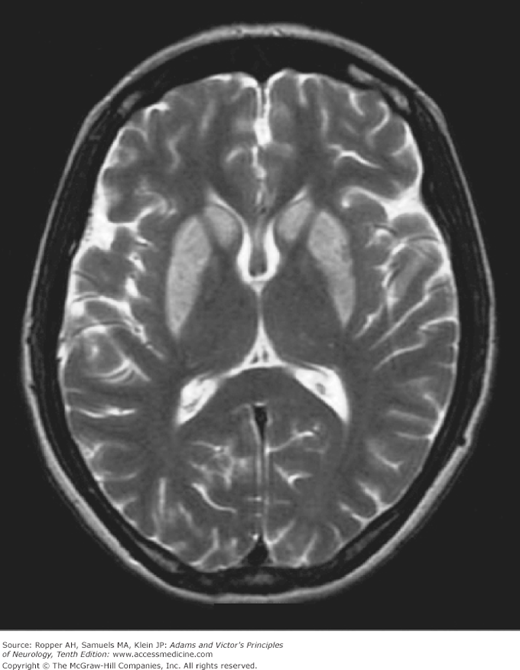

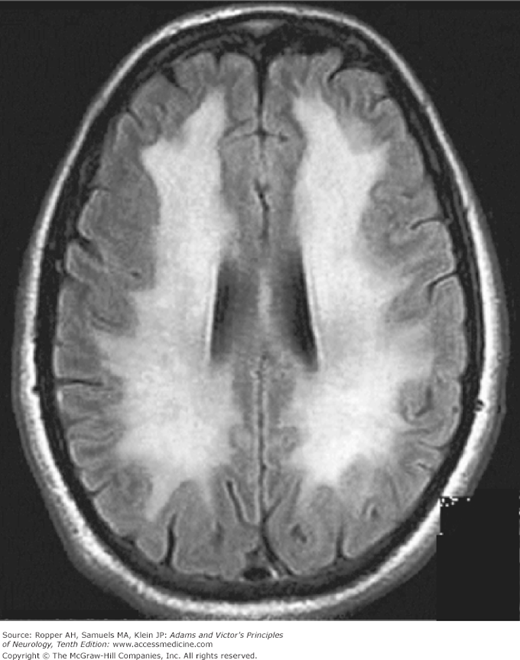

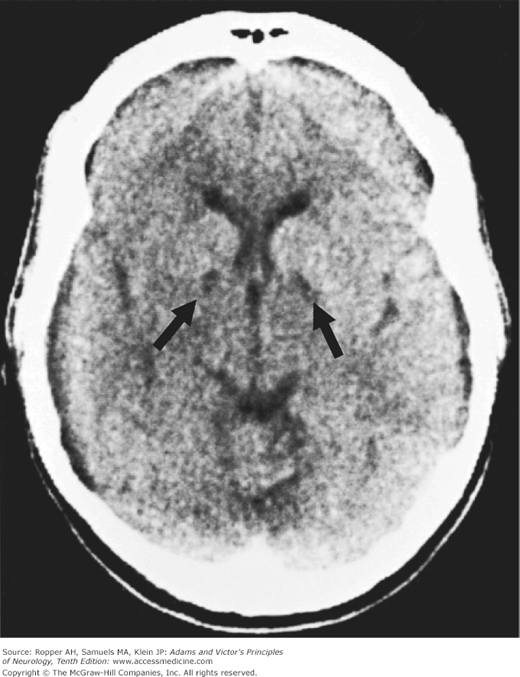

The findings on imaging studies vary. The most common early change in cases of severe injury is a loss of the distinction between the cerebral gray and white matter (Fig. 40-1); patients with this finding are invariably comatose and few awaken with a good neurologic outcome. With less severe and predominantly hypotensive-ischemic events such as cardiac arrest, watershed infarctions become evident in the border zones between the anterior, middle, and posterior cerebral arteries (Fig. 40-2). The clinical syndromes associated with watershed infarction are discussed below. Yet another pattern of brain destruction, seen at times also in CO poisoning, consists of striatal damage that is evident more by imaging than by clinical features (Fig. 40-3).

Figure 40-3.

T2-weighted MRI of striatal damage after anoxia from hanging. The pallidum is spared, in contrast to typical cases of carbon monoxide poisoning (see Fig. 40-5).

(See Chap. 17 for a full discussion)

This represents the most severe degree of hypoxia, usually caused by circulatory arrest; it is manifest by a state of complete unawareness and unresponsiveness with abolition of all brainstem reflexes. Natural respiration cannot be sustained; only cardiac action and blood pressure are maintained. No electrical activity is seen in the EEG (it is isoelectric). At autopsy one finds that most, if not all, the gray matter of cerebral, cerebellar, and brainstem structures—and in some instances, even the upper cervical spinal cord—has been severely damaged.

One must always exercise caution in concluding that a patient has this form of irreversible brain damage, because anesthesia, intoxication with certain drugs, and hypothermia may also cause deep coma and an isoelectric EEG but permit recovery. Therefore it is often advisable to repeat the clinical and laboratory tests after an interval of a day or so, during which time the results of toxic screening also become available. The authors’ experience corroborates the general notion that the vital functions of patients with the brain death syndrome usually cannot be sustained for more than several days; in other words, the problem settles itself. In exceptional cases, however, the provision of adequate fluid, vasopressors, and respiratory support allows preservation of the body in a comatose state for longer periods.

The permanent neurologic sequelae or posthypoxic syndromes observed most frequently are as follows:

Persistent coma or stupor, described above

With lesser degrees of cerebral injury, dementia with or without extrapyramidal signs

Extrapyramidal (parkinsonian) syndrome with cognitive impairment (discussed in relation to CO poisoning)

Choreoathetosis

Cerebellar ataxia

Intention or action myoclonus (Lance-Adams syndrome)

An amnesic state

If hypoperfusion dominates, the patient may also display the manifestations of watershed infarctions that are situated between the end territories of the major cerebral vessels. The main syndromes that become evident soon after the patient awakens are:

Visual agnosias including Balint syndrome and cortical blindness (Anton Syndrome) (see Chap. 22), representing infarctions of the watershed between the middle and posterior cerebral arteries (see Fig. 40-2)

Proximal arm and shoulder weakness, sometimes accompanied by hip weakness (referred to as a “man-in-the-barrel” syndrome), reflecting infarction in the territory between the middle and anterior cerebral arteries. These patients are able to walk, but their arms dangle and their hips may be weak.

The two watershed syndromes may rarely coexist. The interested reader may consult the appropriate chapter in the text on neurologic intensive care by Ropper and colleagues for further details. There are also watershed areas in the spinal cord (Chap. 44).

Seizures may or may not be a problem, and they are often resistant to treatment. Well-formed motor convulsions are infrequent. Myoclonus is more common and may be intermixed with fragmentary convulsions. Myoclonus is a grave sign in most cases but it generally recedes after several hours or a few days. These movements are also difficult to suppress, as noted further on.

This is a relatively uncommon and unexplained phenomenon. Initial improvement, which appears to be complete, is followed after a variable period of time (1 to 4 weeks in most instances) by a relapse, characterized by apathy, confusion, irritability, and occasionally agitation or mania. Most patients survive this second episode, but some are left with serious mental and motor disturbances (Choi; Plum et al). In still other cases, there appears to be progression of the initial neurologic syndrome with additional weakness, shuffling gait, diffuse rigidity and spasticity, sphincteric incontinence, coma, and death after 1 to 2 weeks. Exceptionally, there is yet another syndrome in which an episode of hypoxia is followed by slow deterioration, which progresses for weeks to months until the patient is mute, rigid, and helpless. In such cases, the basal ganglia are affected more than the cerebral cortex and white matter as in the case studied by our colleagues Dooling and Richardson. Instances have followed cardiac arrest, drowning, asphyxiation, and carbon monoxide poisoning.

The imaging features of the white matter disorder can be quite striking (Fig. 40-4). A mitochondrial disorder has been suggested, on uncertain grounds, as the underlying mechanism.

Several validated models have been developed to predict the outcome of anoxic-ischemic coma. All of them incorporate simple clinical features involving loss of motor, verbal, and pupillary functions in various combinations. The most often cited study of the prognostic aspects of coma following cardiac arrest is the one by Levy and colleagues of 210 patients, which provided the following guidelines: 13 percent of patients attained a state of independent function within 1 year; at the time of the initial evaluation, approximately 25 percent of patients had absent pupillary light reflexes, none of whom regained independent function; by contrast, the presence on admission of reactive pupils, eye movements, and any motor response, a configuration displayed in approximately 10 percent, was associated with a better prognosis in almost 50 percent of cases. The absence of neurologic function in any of these spheres at 1 day after cardiac arrest, unsurprisingly, was associated with an even poorer outcome. Similarly, Booth and colleagues analyzed previously published studies and determined that 5 clinical signs at 1 day after cardiac arrest predicted a poor neurologic outcome or death: (1) absent corneal responses, (2) absent pupillary reactivity, (3) no withdrawal to pain, and (4) the absence of any motor response. The use of somatosensory evoked potentials in the prognostication of coma is discussed in Chaps. 2 and 17.

Most workers in the field of coma studies have been unable to establish signs that confidently predict a good outcome. The role of somatosensory evoked potentials in prognosis of coma has been addressed in Chap. 17.

In any such case, concurrent intoxication must, of course, be excluded.

The question of what to do with patients in such states of protracted coma is a societal as much as a medical problem. The neurologist can be expected to state the level and degree of brain damage, its cause, and the prognosis based on his own and published experience. One prudently avoids heroic, lifesaving therapeutic measures once the nature of this state has been determined with certainty.

Treatment is directed initially to the prevention of further hypoxic injury. A clear airway is secured, cardiopulmonary resuscitation is initiated, and every second counts in their prompt utilization. Oxygen may be of value during the first hours but is probably of little use after the blood becomes well oxygenated. Once cardiac and pulmonary function are restored, there is experimental and clinical evidence that reducing cerebral metabolic requirements by inducing hypothermia may have a slight beneficial effect on outcome and may prevent the delayed worsening referred to above, though a recent clinical trial brings this into question (see further on). The use of high-dose barbiturates has not met with the same success.

Much attention was drawn to the randomized trials conducted by Bernard and colleagues and by the Hypothermia After Cardiac Arrest Study Group, of mild hypothermia applied to unconscious patients immediately after cardiac arrest. They reduced the core temperature to 33°C (91°F) within 2 h of the arrest and sustained this level for 12 h in the first trial, and between 32°C and 34°C for 24 h in the second study. Both trials demonstrated improved survival and better cognitive outcome in survivors, compared to leaving the patient in a normothermic state and this led to the development of guidelines and a change in clinical practice in the U.S. and elsewhere after 2002. The outcomes were evaluated by coarse measures of neurologic function. Implementing and sustaining hypothermia, either by external cooling, infusion of cooled normal saline, or intravenous cooling devices is difficult, and the iatrogenic problems of hypotension, bleeding, ventricular ectopy and infection have sometimes arisen, although this mild degree of temperature reduction is usually well tolerated. A third larger trial conducted by Nielsen and colleagues compared temperature maintenance after cardiac arrest at 33°C to maintenance of 36°C and found no difference in the rate of death or in neurological outcome. The results of this third study are still being discussed and it is not clear if it should be interpreted as demonstrating that hypothermic treatment is ineffective or if the avoidance of even mild hyperthermia, observed in the control groups of previous trials, was the important factor in improving outcome. At the time of this writing, it seems to us that induced hypothermia is not obligatory after cardiac arrest but that attempts should be made to keep the body temperature from rising above normal.

Vasodilator drugs, glutamate blockers, opiate antagonists, and calcium channel blockers have been of no proven benefit despite their theoretical appeal and some experimental successes. Corticosteroids ostensibly help to allay brain (possibly cellular) swelling, but, again, their therapeutic benefit has not been evident in clinical trials.

Seizures should be controlled by the methods indicated in Chap. 16. If convulsions are severe, continuous, and unresponsive to the usual medications, continuous infusion of a drug such as midazolam or propofol, and eventually the suppression of convulsions with neuromuscular blocking agents may be required. Often the seizures cease after a few hours and are replaced by polymyoclonus. For the latter, clonazepam, 8 to 12 mg daily in divided doses may be useful but the commonly used antiepileptic drugs have little effect. A state of spontaneous and stimulus-sensitive myoclonus as well as persistent limb posturing usually presages a poor outcome. The striking disorder of delayed movement-induced myoclonus and ataxic tremor that appear after the patient awakens from an anoxic episode (Lance-Adams myoclonus) is a special issue, which is discussed in Chap. 6. Its treatment usually requires the use of multiple medications. Fever is treated with antipyretics or a cooling blanket combined with neuromuscular paralyzing agents.

Strictly speaking, CO is an exogenous toxin, but it is considered here because it produces a characteristic cerebral injury and is frequently associated with delayed neurologic deterioration. The extreme affinity of CO for hemoglobin (more than 200 times that of oxygen) drastically reduces the oxygen content of blood and subjects the brain to prolonged hypoxia and acidosis. Cardiac toxicity and hypotension generally follow. Whether CO also has a direct toxic action on neuronal components is not settled. The effects on the brain for the most part simulate those caused by cardiac arrest. Neurologists are likely to encounter instances of CO poisoning in burn units and in patients who have attempted suicide or have been exposed accidentally to a faulty furnace or to car exhaust in a closed garage. A contemporary review of the subject has been given by Weaver.

Early symptoms include headache, nausea, dyspnea, confusion, dizziness, and clumsiness. These occur when the carboxyhemoglobin level reaches 20 to 30 percent of total hemoglobin. Exposure to relatively low levels of CO from faulty furnaces and gasoline engines should be suspected as the cause of recurrent headaches and confusion that clear upon hospitalization or other change of venue. A cherry-red color of the skin may appear, but is actually an infrequent finding; cyanosis is more common. At slightly higher levels of carboxyhemoglobin, blindness, visual field defects, and papilledema develop, and levels of 50 to 60 percent are associated with coma, decerebrate or decorticate posturing, seizures in a few patients, and generalized slowing of the EEG rhythms. The initial CT scanning is normal or shows mild cerebral edema; later scans may show a characteristic lesion in the pallidum, as described below. Only if there has been associated hypotension does one see the same types of vascular border-zone infarctions that appear after cardiac arrest.

Delayed neurologic deterioration 1 to 3 weeks (sometimes much longer) after CO exposure occurs more frequently than with other forms of cerebral hypoxia. In Choi’s survey, this feature was observed in 3 percent of 2,360 cases of CO poisoning and in 12 percent of those ill enough to be admitted to a hospital. Extrapyramidal features (parkinsonian gait and bradykinesia) predominated. Three-quarters of such patients were said to recover within a year. Discrete lesions centered in the globus pallidus bilaterally and sometimes the inner portion of the putamina are characteristic of CO poisoning that had produced coma (Fig. 40-5), but similar focal destruction may be seen after drowning, strangulation, and other forms of anoxia. The common feature among the delayed-relapse patients is a prolonged period of pure anoxia (before the occurrence of ischemia). Basal ganglia lesions may be quite prominent on CT scans even when delayed neurologic sequelae do not occur but they are invariably present between 1 and 4 weeks in patients who develop the delayed extrapyramidal syndrome. In less-severely affected patients we have seen such lesions resolve entirely on CT and MRI and there is no resultant movement disorder.

The initial treatment for carbon monoxide exposure is with inspired oxygen. Because the half-life of CO (normally 5 h) is greatly reduced by the administration of hyperbaric oxygen at 2 or 3 atmospheres, this additional treatment is recommended when the carboxyhemoglobin concentration is greater than 40 percent or in the presence of coma or seizures (Myers et al). According to a trial conducted by Weaver and colleagues, this treatment reduces the incidence of cognitive sequelae from 46 to 25 percent. They administered 3 hyperbaric sessions in the first 24 h after exposure to CO.

Acute mountain sickness is another special form of cerebral hypoxia. It occurs when a sea-level inhabitant abruptly ascends to a high altitude. Headache, anorexia, nausea and vomiting, weakness, and insomnia appear at altitudes above 8,000 ft; on reaching higher altitudes, there may be ataxia, tremor, drowsiness, mild confusion, and hallucinations. At 16,000 ft, according to Griggs and Sutton, 50 percent of individuals develop asymptomatic retinal hemorrhages, and it has been suggested that such hemorrhages also occur in the cerebral white matter. Extreme altitude sickness may result in fatal cerebral edema. The overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a protein originally noted for its effects on vascular permeability, has been implicated as the cause of cerebral edema in the experiments of Schoch and colleagues. With more prolonged exposure at these altitudes or with further ascent, affected individuals suffer mental impairment that may progress to coma. Hypoxemia at high altitudes is intensified during sleep, as ventilation normally diminishes and also by pulmonary edema, another manifestation of mountain sickness. Reference was made earlier to the observation of Hornbein and colleagues of a mild, but possibly lasting, memory impairment even in acclimated mountaineers who had been exposed to extremely high altitudes for several days. Hackett and Roach have reviewed the treatments for altitude illness.

Chronic mountain sickness, also called Monge disease (after the physician who described the condition in Andean Indians of Peru), is observed in long-term inhabitants of high-altitude mountainous regions. Pulmonary hypertension, cor pulmonale, and secondary polycythemia are the main features. There is usually hypercarbia as well, with the expected degree of mild mental dullness, slowness, fatigue, nocturnal headache, and, sometimes, papilledema (see below). Thomas and colleagues have called attention to a syndrome of burning hands and feet in Peruvians at high altitude, apparently a maladaptive response to chronic hypoxia.

Sedatives, alcohol, and a slightly elevated Pco2 in the blood all reduce tolerance to high altitude. Dexamethasone and acetazolamide prevent and counteract mountain sickness to some extent. The most effective preventive measure is acclimatization by a 2- to 4-day stay at intermediate altitudes.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease such as emphysema, fibrosing lung disease, neuromuscular weakness, and, in some instances, inadequacy of the medullary respiratory centers each may lead to persistent respiratory acidosis, with elevated of Pco2 and reduced in arterial PO2. The complete clinical syndrome of chronic hypercapnia described by Austen, Carmichael, and Adams comprises headache, papilledema, mental dullness, drowsiness, confusion, stupor and coma, and asterixis. More typically, only some of these features are found. Some patients have a fast-frequency tremor. The headache tends to be generalized, frontal, or occipital and can be quite intense, persistent, steady, and aching in type; nocturnal occurrence is a feature of some cases. The papilledema is bilateral but may be slightly greater in one eye than in the other, and hemorrhages may encircle the choked disc (a later finding). The tendon reflexes are lively and plantar reflexes may be extensor. Intermittent drowsiness, inattentiveness, reduction of psychomotor activity, inability to perceive all the items in a sequence of events, and forgetfulness constitute the more subtle manifestations of this syndrome and may prompt the family to seek medical help. Such symptoms may last only a few minutes or hours, and one cannot count on their presence at the time of a particular examination. In fully developed cases, the CSF is under increased pressure; Pco2 may exceed 75 mm Hg, and the O2 saturation of arterial blood ranges from 85 percent to as low as 40 percent. The EEG shows slow activity in the delta or theta range, which is sometimes bilaterally synchronous.

The mechanism of the cerebral disorder is from a direct CO2 narcosis, but the biochemical details are not known. Normally the CSF is slightly acidotic in comparison to the blood and the Pco2 of the CSF is about 10 mm Hg higher than that of the blood. With respiratory acidosis, the pH of the CSF falls (into the range of 7.15 to 7.25) and cerebral blood flow increases as a result of cerebral vasodilatation. However, the brain rapidly adapts to respiratory acidosis through the generation and secretion of bicarbonate by the choroid plexuses. Brain water content also increases, mainly in the white matter. In animal models of hypercarbia, blood and brain NH3 is elevated, which may explain the similarity of the syndrome to that of hyperammonemic liver failure (Herrera and Kazemi).

The most effective therapeutic measures are positive-pressure ventilation, using oxygen if there is also hypoxia. Oxygen supplementation is, of course, used cautiously in these patients in order to avoid suppressing respiratory drive; marginally compensated patients treated with excessive oxygen have lapsed into coma. Treatment of heart failure, phlebotomy to reduce the viscosity of the blood, and antibiotics to suppress pulmonary infection may be necessary. Often these measures result in a surprising degree of improvement, which may be maintained for months or years.

Unlike pure hypoxic encephalopathy, prolonged coma because of hypercapnia is relatively rare and in our experience has not led to irreversible brain damage. Papilledema, myoclonus, and especially asterixis are important diagnostic features. If aminophylline is administered for the treatment of the underlying pulmonary airway disease, it may produce high blood levels and a tendency for it to produce seizures.

This condition is now relatively infrequent but is an important cause of confusion, convulsions, stupor, and coma; as such, it merits separate consideration as a metabolic disorder of the brain. The essential biochemical abnormality is a critical lowering of the blood glucose. At a level of about 30 mg/dL, the cerebral disorder takes the form of a confusional state and one or more seizures may occur; at a level of 10 mg/dL, there is coma that may result in irreparable injury to the brain if not corrected immediately by the administration of glucose. As with most other metabolic encephalopathies, the rate of decline of blood glucose is a factor in both the depression of consciousness and residual dementia.

The normal brain has a glucose reserve of 1 to 2 g (30 mmol/100 g of tissue), mostly in the form of glycogen. Because glucose is utilized by the brain at a rate of 60 to 80 mg/min, the glucose reserve may sustain cerebral activity for 30 min or less once blood glucose is no longer available. Glucose is transported from the blood to the brain by an active carrier system. Glucose entering the brain either undergoes glycolysis or is stored as glycogen. During normal oxygenation (aerobic metabolism), glucose is converted to pyruvate, which enters the Krebs cycle; with anaerobic metabolism, lactate is formed. The oxidation of 1 mole of glucose requires 6 mole of O2. Of the glucose taken up by the brain, 85 to 90 percent is oxidized; the remainder is used in the formation of proteins and other substances, notably neurotransmitters and particularly gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA).

When blood glucose falls, the central nervous system (CNS) can utilize nonglucose substrates to a variable extent for its metabolic needs, especially keto acids and intermediates of glucose metabolism, such as lactate, pyruvate, fructose, and other hexoses. In the neonatal brain, which has a higher glycogen reserve, keto acids provide a considerable proportion of cerebral energy requirements; this also happens after prolonged starvation. However, in the face of severe and sustained hypoglycemia, these alternative substrates are inadequate to preserve the structural integrity of neurons, and eventually adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is depleted as well. If convulsions occur, they usually do so during a period of confusion; the convulsions have been attributed to an altered integrity of neuronal membranes and to elevated NH3 and depressed GABA and lactate levels (Wilkinson and Prockop).

The brain is the only organ besides the heart that suffers severe functional and structural impairment under conditions of severe hypoglycemia. Beyond what is described above, the pathophysiology of the cerebral disorder has not been fully elucidated. It is known that hypoglycemia reduces O2 uptake and increases cerebral blood flow. As with anoxia and ischemia, there is experimental evidence that the excitatory amino acid glutamate is involved in the process. The levels of several brain phospholipid fractions decrease when animals are given large doses of insulin. However, the suggestion that hypoglycemia results in a rapid depletion and inadequate production of high-energy phosphate compounds has not been corroborated; some other glucose-dependent biochemical processes must be implicated.

The most common causes of hypoglycemic encephalopathy are: (1) accidental or deliberate overdose of insulin or an oral diabetic agent; (2) islet cell insulin-secreting tumor of the pancreas; (3) depletion of liver glycogen, which occasionally follows a prolonged alcoholic binge, starvation, or any form of severe liver failure; (4) glycogen storage disease of infancy; and (5) an idiopathic hypoglycemia in the neonatal period and infancy; (6) subacute and chronic hypoglycemia from islet cell hypertrophy and islet cell tumors of the pancreas, carcinoma of the stomach, fibrous mesothelioma, carcinoma of the cecum, and hepatoma. Purportedly, an insulin-like substance is elaborated by these nonpancreatic tumors. In the past, hypoglycemic encephalopathy was a not infrequent complication of “insulin shock” therapy for schizophrenia. In functional hyperinsulinism, as occurs in anorexia nervosa and dietary faddism, the hypoglycemia is rarely of sufficient severity or duration to damage the CNS.

The initial symptoms appear when the blood glucose has descended to about 30 mg/dL, nervousness, hunger, flushed facies, sweating, headache, palpitation, trembling, and anxiety. These gradually give way to confusion and drowsiness or occasionally, to excitement, overactivity, and bizarre or combative behavior. Many of the early symptoms relate to adrenal and sympathetic overactivity and some of the manifestations may be muted in diabetic patients with neuropathy. In the next stage, forced sucking, grasping, motor restlessness, muscular spasms, and decerebrate rigidity occur, in that sequence. Myoclonic twitching and convulsions develop in some patients. Rarely, there are focal cerebral deficits, the pathogenesis of which remains unexplained; according to Malouf and Brust, hemiplegia, corrected by intravenous glucose, was observed in 3 of 125 patients who presented with symptomatic hypoglycemia.

Blood glucose levels of approximately 10 mg/dL are associated with deep coma, dilatation of pupils, pale skin, shallow respiration, slow pulse and hypotonia, what had in the past been termed the “medullary phase” of hypoglycemia. If glucose is administered before this level has been attained, the patient can be restored to normal, retracing the aforementioned steps in reverse order. However, once this state is reached, and particularly if it persists for more than a few minutes, recovery is delayed for a period of days or weeks and may be incomplete as noted below.

The EEG is altered as the blood glucose falls, but the correlations are imprecise. There is diffuse slowing in the theta or delta range. During recovery, sharp waves may appear and coincide in some cases with seizures.

The major clinical differences between hypoglycemic and hypoxic encephalopathy lie in the setting and the mode of evolution of the neurologic disorder. The effects of hypoglycemia usually unfold more slowly, over a period of 30 to 60 min, rather than in a few seconds or minutes. The recovery phase and sequelae of the 2 conditions are quite similar.

A large dose of insulin, which produces intense hypoglycemia, even of relatively brief duration (30 to 60 min), is more dangerous than a series of less-severe hypoglycemic episodes from smaller doses of insulin, possibly because the former impairs or exhausts essential enzymes, a condition that cannot then be overcome by large quantities of intravenous glucose. Reflecting the benignity of repeated minor occurrences, the Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Study Research Group have demonstrated that recurrent hypoglycemic episodes in the course of treatment of diabetes over many years are very well tolerated and do not lead to cognitive decline.

A severe and prolonged episode of hypoglycemia may result in permanent impairment of intellectual function as well as other neurologic residua, like those that follow severe anoxia. We also have observed states of protracted coma, as well as relatively pure Korsakoff amnesia. However, one should not be hasty in prognosis, for we have observed slow improvement to continue for 1 to 2 years.

Recurrent hypoglycemia from an islet cell tumor may masquerade for some time as an episodic confusional psychosis or convulsive illness; diagnosis then awaits the demonstration of low blood glucose or hyperinsulinism in association with the neurologic symptoms. We saw a man in the emergency department whose main complaint was episodic inability to dial a touchtone telephone and a mild mental fogginess; he was found to have an insulinoma.

Functional or reactive hypoglycemia is the most ambiguous of all syndromes related to low blood glucose. This condition is usually idiopathic but may precede the onset of diabetes mellitus. The rise of insulin in response to a carbohydrate meal is delayed but then causes an excessive fall in blood glucose, to 30 to 40 mg/dL. The symptoms are malaise, fatigue, nervousness, headache and tremor, which may be difficult to distinguish from anxious depression. Not surprisingly, the term functional hypoglycemia has been much abused, being applied indiscriminately to a variety of complaints that would now be called chronic fatigue syndrome or an anxiety syndrome. In fact, a syndrome attributable to functional or reactive hypoglycemia is infrequent and its diagnosis requires the finding of an excessive reaction to insulin, low blood glucose during the symptomatic period, and a salutary response to oral glucose.

In all forms of hypoglycemic encephalopathy, the major damage is to the cerebral cortex. Cortical nerve cells degenerate and are replaced by microglia cells and astrocytes. The distribution of lesions is similar, although probably not identical to that in hypoxic encephalopathy. The cerebellar cortex is less vulnerable to hypoglycemia than to hypoxia. Auer has described the ultrastructural changes in neurons resulting from experimental hypoglycemia; with increasing duration of hypoglycemia and EEG silence, there are mitochondrial changes, first in dendrites and then in nerve cell soma, followed by nuclear membrane disruption leading to cell death.

Treatment of all forms of hypoglycemia obviously consists of correction of the hypoglycemia at the earliest possible moment. It is not known whether hypothermia or other measures will increase the safety period in hypoglycemia or alter the outcome. Seizures and twitching may not stop with antiepileptic drugs until the hypoglycemia is corrected.

Two syndromes have been defined, mainly in diabetics: (1) hyperglycemia with ketoacidosis and (2) hyperosmolar nonketotic hyperglycemia.

In diabetic acidosis, the familiar picture is one of dehydration, fatigue, weakness, headache, abdominal pain, dryness of the mouth, stupor or coma, and Kussmaul type of breathing. Usually the condition has developed over a period of days in a patient known or proven to be diabetic. Often, the patient had failed to take a regular insulin dose. The blood glucose level is found to be more than 400 mg/dL, the pH of the blood less than 7.20, and the bicarbonate less than 10 mEq/L. Ketone bodies and β-hydroxybutyric acid are elevated in the blood and urine, and there is marked glycosuria. The prompt administration of insulin and repletion of intravascular volume correct the clinical and chemical abnormalities over a period of hours.

A small group of patients with diabetic ketoacidosis, such as those reported by Young and Bradley, develop deepening coma and cerebral edema as the elevated glucose is corrected. Mild cerebral edema is commonly observed in children during treatment with fluids and insulin (Krane et al). Prockop attributed this condition to an accumulation of fructose and sorbitol in the brain. The latter substance, a polyol that is formed during hyperglycemia, crosses membranes slowly, but once it does so, is said to cause a shift of water into the brain and an intracellular edema. However, according to Fishman (1974), the increased polyols in the brain in hyperglycemia are not present in sufficient concentration to be important osmotically; though they may induce other metabolic effects related to the encephalopathy. These are matters of conjecture, as the increase of polyols has never been found. The brain edema in this condition is probably a result of reversal of the osmolality gradient from blood to brain, which occurs with rapid correction of hyperglycemia.

The pathophysiology of the cerebral disorder in diabetic ketoacidosis is not fully understood. No consistent cellular pathology of the brain has been identified in the cases we have examined. Factors such as ketosis, tissue acidosis, hypotension, hyperosmolality, and hypoxia have not been identified. Attempts at therapy by the administration of urea, mannitol, salt-poor albumin, and dexamethasone are usually unsuccessful, though recoveries are reported.

In hyperosmolar nonketotic hyperglycemia, the blood glucose is extremely high, more than 600 mg/dL, but ketoacidosis does not develop, or if it does develop, it is mild. Osmolality is usually in excess of 330 mOsm/L. There is also hemoconcentration and prerenal azotemia. Appreciation of the neurologic syndrome is generally credited to Wegierko, who published descriptions of it in 1956 and 1957. Most of the patients are elderly diabetics but some were not previously known to have been diabetic. An infection, enteritis, pancreatitis, dehydration, or a drug known to upset diabetic control (thiazides, corticosteroids, and phenytoin) leads to polyuria, fatigue, confusion, stupor, and coma. Often the syndrome arises in conjunction with the combined use of corticosteroids and phenytoin (which inhibits insulin release), for example, in elderly patients with brain tumors. The use of osmotic diuretics enhances the risk.

Seizures and focal signs such as a hemiparesis, a hemisensory defect, choreoathetosis, or a homonymous visual field defect are more common than in any other metabolic encephalopathy and may erroneously suggest the possibility of a stroke. Fluids should be replaced cautiously, using isotonic saline and potassium. Correction of the markedly elevated blood glucose requires relatively small amounts of insulin, since these patients often do not have a high degree of insulin resistance.

Chronic hepatic insufficiency with portosystemic shunting of blood is punctuated by episodes of stupor, coma, and other neurologic symptoms—a state referred to as hepatic stupor, coma, or encephalopathy. It was clearly delineated by Adams and Foley over 50 years ago. This state complicates all varieties of liver disease and is unrelated to jaundice or ascites. Any form of shunting, even without hepatic disease, such as surgical portal–systemic shunt (Eck fistula) is attended by the same clinical picture (see further on). There are also a number of hereditary hyperammonemic syndromes, usually first apparent in infancy or childhood (discussed extensively in Chap. 37) that lead to episodic coma with or without seizures. In all these states, it is common for an excess of protein derived from the diet or from gastrointestinal hemorrhage to induce or worsen the encephalopathy. Additional predisposing factors are hypoxia, hypokalemia, metabolic alkalosis, excessive diuresis, use of sedative hypnotic drugs, and constipation. A special from of the syndrome in epilepsy patients exposed to valproate; confusion and ataxia may occur acutely or subacutely in these patients (Gomcelli et al). Reye syndrome following viral infections in children, now infrequent, was also associated with very high levels of ammonia in the blood and encephalopathy (see further on).

The clinical picture of acute, subacute, or chronic hepatic encephalopathy consists of a derangement of consciousness, presenting first as mental slowing and confusion, occasionally with hyperactivity, followed by progressive drowsiness, stupor, and coma. The confusional state is combined with a characteristic intermittency of sustained muscle contraction; this phenomenon, which was originally described in patients with hepatic stupor by Adams and Foley and called asterixis (from the Greek sterixis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree