Diseases of the Nervous System Caused by Nutritional Deficiency: Introduction

Among nutritional disorders, those of the nervous system occupy a position of special interest and importance. The early studies of beriberi at the turn of the twentieth century were largely responsible for the discovery of thiamine and consequently for the modern concept of deficiency disease. A series of notable achievements in the science of nutrition followed the discovery of vitamins. Despite such progress, a number of diseases caused by nutritional deficiency, and particularly those of the nervous system, continue to represent a worldwide health problem of serious proportions. In some communities, where the diet consists mainly of highly milled rice, there is still a significant incidence of beriberi. In some developing countries, deficiency diseases are endemic, the result of chronic dietary deprivation. And the ultimate effects on the nervous system of intermittent mass starvation, involving large portions of the African continent, are alarming to contemplate.

It comes as a surprise to many physicians that deficiency diseases still occur in the United States and other parts of the developed world. To some extent this is attributable to the prevalence of alcoholism. Relatively less common causes are dietary faddism and impaired absorption of dietary nutrients, which occurs in patients with celiac sprue, pernicious anemia, or surgical exclusion of portions of the gastrointestinal tract for treatment of obesity, and the wasting syndromes of cancer and AIDS. Finally, there are iatrogenic deficiencies induced by the use of vitamin antagonists or certain drugs, such as isonicotinic acid hydrazide (INH), which is used in the treatment of tuberculosis and interferes with the enzymatic function of pyridoxine or methotrexate.

The term deficiency is used throughout this chapter in its strictest sense to designate disorders that result from the lack of an essential nutrient or nutrients in the diet or from a conditioning factor that increases the need for these nutrients. The most important of these are the vitamins, more specifically, members of the B group—thiamine, nicotinic acid, pyridoxine, pantothenic acid, riboflavin, folic acid, and cobalamin (vitamin B12). However, some deficiency diseases cannot be related to the lack of a single vitamin. Usually the effects of several vitamin deficiencies can be recognized (thiamine deficiency causing Wernicke disease and subacute combined degeneration [SCD] of the cord, as a result of vitamin B12 deficiency, are notable exceptions that are due to single deficiencies).

Furthermore, nutritional diseases of the nervous system are not simply a matter of vitamin deprivation. The general signs of undernutrition, such as circulatory abnormalities and loss of subcutaneous fat and muscle bulk, are usually associated and conversely, a total lack of vitamins, as in starvation, is rarely associated with the classic deficiency syndromes of beriberi or pellagra. In other words, a certain amount of food is necessary to produce them. In a similar way, excessive intake of carbohydrates relative to the supply of thiamine favors the development of a thiamine-deficiency state. All deficiency diseases, including those of the nervous system, are influenced by factors such as exercise, growth, pregnancy, neoplasia, and systemic infection, which increase the need for essential nutrients, and by disorders of the liver and the gastrointestinal tract, which may interfere with the synthesis and absorption of these nutrients.

As already mentioned, alcoholism is an important factor in the causation of nutritional diseases of the nervous system. Alcohol acts mainly by displacing food in the diet but also by adding carbohydrate calories (alcohol is burned almost entirely as carbohydrates), thus increasing the need for thiamine. There is some evidence as well that alcohol impairs the absorption of thiamine and other vitamins from the gastrointestinal tract.

In infants and young children, a reduction in protein and caloric intake (so-called protein-calorie malnutrition [PCM]) has a devastating effect on body growth. Whether or not PCM also hinders the growth of the brain, with consequent effects on intellectual and behavioral development, cannot be answered as readily. The data bearing on this matter are discussed in the last part of this chapter.

Characteristic of the nutritional diseases is the potential for involvement of both the central and peripheral nervous systems, an attribute shared only with certain metabolic disorders. In addition, there are several distinctive neurologic disorders in which nutritional deficiency may play a role, although this has not been proved. These include (1) “alcoholic” cerebellar degeneration, (2) Marchiafava-Bignami disease (degeneration of the corpus callosum), and (3) central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis, which are more closely aligned with the rapid correction of hyponatremia, as discussed in Chap. 40.

Some comments will also be made in this chapter about PCM, the neurologic disorders consequent to intestinal malabsorption, and the rare hereditary vitamin-responsive diseases. Deficiencies of trace elements, because of their rarity, are not discussed; only iodine deficiency (cretinism) is of much importance in humans, and it was discussed in Chap. 40 on acquired metabolic diseases.

Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome (Thiamine [B1] Deficiency)

Wernicke disease and the Korsakoff amnesic state are common neurologic disorders that have been recognized since the 1880s. Wernicke disease is characterized by nystagmus, abducens and conjugate gaze palsies, ataxia of gait, and mental confusion. These symptoms develop acutely or subacutely and may occur singly or, more often, in combination. Wernicke disease is specifically the result of a deficiency of thiamine and is observed mainly, although far from exclusively, in alcoholics.

The Korsakoff amnesic state (Korsakoff psychosis) is a mental disorder in which retentive memory is impaired out of proportion to all other cognitive functions in an otherwise alert and responsive patient. This amnesic disorder, like Wernicke disease, is most often associated with the thiamine deficiency of alcoholism and malnutrition, but it may be a symptom of various other non-nutritional diseases that have their basis in structural lesions of the medial thalami or the hippocampal portions of the temporal lobes, such as infarction in the territory of branches of the posterior cerebral arteries, hippocampal damage after cardiac arrest, third ventricular tumors, and herpes simplex encephalitis. An almost equivalent type of memory disturbance may also follow acute lesions of the basal septal nuclei of the frontal lobe. Transient impairments of retentive memory of the Korsakoff type may be the salient manifestations of temporal lobe epilepsy, concussive head injury, and a unique disorder known as transient global amnesia. The anatomic basis of the Korsakoff amnesic syndrome is described in Chap. 21.

In the nutritionally deficient patient, Korsakoff amnesia is usually associated with and immediately follows the occurrence of Wernicke disease. For this reason and others elaborated in the following text, the term Wernicke disease or Wernicke encephalopathy is applied to a symptom complex of ophthalmoparesis, nystagmus, ataxia, and an acute apathetic–confusional state. If an enduring defect in learning and memory results, as it often does, the symptom complex is designated as the Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome.

It is perhaps in part due to the emphasis in previous editions of this book that alcoholism has been inordinately associated with this disease complex. The disease arises in many other clinical settings. One of Wernicke’s original cases, for example, occurred in a woman with hyperemesis gravidarum and such instances are still found. However, bariatric surgery, cancer chemotherapy, inanition in AIDS and from anorexia nervosa, and even in the frailty of older age, in nutritionally susceptible persons, starvation for economic and social reasons all may give rise to thiamine deficiency. Even the elderly and frail who subsist for years on “tea and toast” can acquire the disease. In addition, there are common medical circumstances in which a subclinical thiamine deficiency becomes manifest. Perhaps the most important of these is a carbohydrate load, particularly the administration of intravenous glucose to a malnourished individual; other precipitants are unbalanced intravenous hyperalimentation, refeeding syndrome, thyrotoxicosis, and hypomagnesemia.

The presence of this disease must be constantly emphasized. As summarized in the review by Sechi and Serra of published series from several countries, there is a discrepancy between the detection of the process in autopsy series, 0.5 to 3 percent, and the prevalence of the clinical diagnosis, 0.04 to 0.13 percent, indicating that approximately three-quarters of cases are not recognized during life.

In 1881, Carl Wernicke first described an illness of sudden onset characterized by paralysis of eye movements, ataxia of gait, and mental confusion. His observations were made in 3 patients, of whom 2 were alcoholics and 1 was a young woman with persistent vomiting following the ingestion of sulfuric acid. In each of these patients there was progressive stupor and coma culminating in death. The pathologic changes described by Wernicke consisted of punctate hemorrhages affecting the gray matter around the third and fourth ventricles and aqueduct of Sylvius; he considered these changes to be inflammatory in nature and confined to the gray matter, hence his designation “polioencephalitis hemorrhagica superioris.” In the belief that Gâyet had described an identical disorder in 1875, the term Gâyet-Wernicke is used frequently by French authors. Such a designation is hardly justified insofar as the clinical signs and pathologic changes in Gâyet’s patients differed from those of Wernicke’s patients in all essential details.

The first comprehensive account of this disorder was given by the Russian psychiatrist S.S. Korsakoff in a series of articles published between 1887 and 1891 (for English translation and commentary, see reference by Victor and Yakovlev). Korsakoff stressed the relationship between “neuritis” (a term used at that time for all types of peripheral nerve disease) and the characteristic alcoholic disorder of memory, which he believed to be “2 facets of the same disease” and which he called “psychosis polyneuritica.” But he also made the points that neuritis need not accompany the amnesic syndrome and that both disorders could affect nonalcoholic as well as alcoholic patients. His clinical descriptions were remarkably complete and have not been surpassed to the present day. It is of interest that the relationship between Wernicke disease and Korsakoff polyneuritic psychosis was appreciated neither by Wernicke nor by Korsakoff. Murawieff, in 1897, first postulated that a single cause was responsible for both. The intimate clinical relationship was established by Bonhoeffer in 1904, who stated that in all cases of Wernicke disease he found neuritis and an amnesic psychosis. Confirmation of this relationship on pathologic grounds came much later. For further details the reader is referred to the extensive monograph by Victor, Adams, and Collins.

The incidence of the Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome cannot be stated with precision, but it had been a common disorder as noted in the introductory comments. At the Cleveland Metropolitan General Hospital, for example, in a consecutive series of 3,548 autopsies in adults (for the period 1963 to 1976), our colleague M. Victor (1990) found the pathognomonic lesions in 77 cases (2.2 percent). The disease affects males slightly more often than females and the age of onset is fairly evenly distributed between 30 and 70 years. In the past few decades, the incidence of the Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome has fallen in the alcoholic population, but it is being recognized with increasing frequency among nonalcoholic patients in a variety of clinical settings that are prone to include malnutrition, including iatrogenic ones.

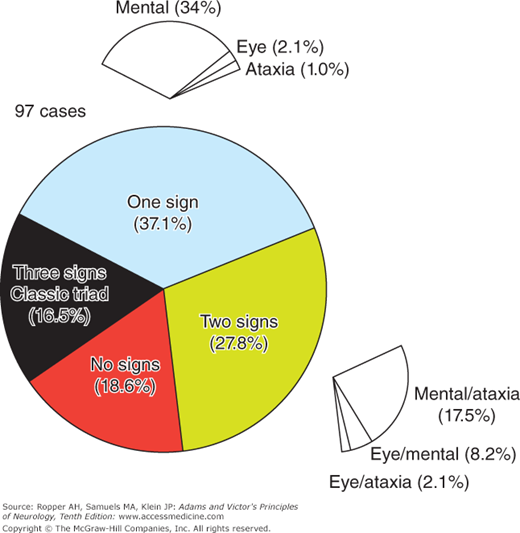

The triad of clinical features described by Wernicke of ophthalmoplegia (with nystagmus), ataxia, and disturbances of mentation and consciousness is still clinically useful provided that the diagnosis is suspected and the signs are carefully sought. Often, the disease begins with ataxia, followed in a few days or weeks by mental confusion; or there may be confusion alone, or the more or less simultaneous onset of ataxia, nystagmus, and ophthalmoparesis with or without confusion. In approximately one-third of cases, one component of this triad may be the sole manifestation of the disease. Timely treatment with thiamine prevents the permanent Korsakoff-amnesic component of the disease. A schematic representation of the various features is shown in Fig. 41-1, adapted from the series of 131 autopsied proved cases described by Harper, Giles, and Finlay-Jones. The notable aspects are that all 3 of the typical signs were present in only 16 percent; 1 sign in 31 percent, usually confusion alone; 2 signs in 28 percent; and no signs reported or detected during life in 19 percent. A description of each of the major manifestations follows.

The diagnosis of Wernicke disease is made most readily on the basis of the ocular signs. These consist of (1) nystagmus that is both horizontal and vertical and mainly evoked by gaze; this is the most common feature, (2) weakness or paralysis of the lateral rectus muscles, and (3) weakness or paralysis of conjugate gaze. Usually there is some combination of these abnormalities (see Chap. 14).

Next to nystagmus, the most frequent ocular abnormality is lateral rectus weakness, which is bilateral but not necessarily symmetrical and is accompanied by diplopia and internal strabismus. With complete paralysis of the lateral rectus muscles, nystagmus is absent in the abducting eyes and it becomes evident as the weakness improves under treatment. The palsy of conjugate gaze varies from merely a paretic nystagmus on extreme gaze to a complete loss of ocular movement in horizontal or vertical movements, abnormalities of the former being more frequent. An isolated paralysis of downward gaze does occur but is an unusual manifestation, and a pattern that simulates internuclear ophthalmoplegia has been seen. In advanced stages of the disease there may be a complete loss of ocular movements and the pupils, which are otherwise usually spared, may become miotic and nonreacting. Ptosis, small retinal hemorrhages, involvement of the near–far focusing mechanism, and evidence of optic neuropathy occur occasionally, but neither we nor our colleagues have observed papilledema that was included in Wernicke’s original description. These ocular signs are highly characteristic of Wernicke disease and disappearance of nystagmus and an improvement in ophthalmoparesis within hours or a day of the administration of thiamine confirms the diagnosis.

Essentially the ataxia is one of stance and gait; in the acute stage of the disease it may be so severe that the patient cannot stand or walk without support. Lesser degrees are characterized by a wide-based stance and a slow, uncertain, short-stepped gait; the mildest degrees are apparent only in tandem walking. In contrast to the gross disorder of locomotion is a relative infrequency of limb ataxia and of intention tremor; when present, they are more likely to be elicited by heel-to-knee than by finger-to-nose testing. Dysarthric, cerebellar-type scanning speech is present only rarely.

These occur in some form in all but 10 percent of patients who have clinical signs. From Fig. 41-1 it can also be appreciated that when there is only one sign of Wernicke disease, it is usually a confusional state. Several related types of disturbed mentation and consciousness are recognized. By far the most common disturbance is a global confusional state. The next following in frequency is memory loss discussed as follows. The patient is apathetic, inattentive, and indifferent to his surroundings. Spontaneous speech is minimal and many questions are left unanswered, or the patient may suspend conversation and drift off to sleep, although he can be aroused without difficulty. Such questions as are answered betray disorientation in time and place, misidentification of those around him, and an inability to grasp the immediate situation. Many of the patient’s remarks may be irrational and lack consistency from one moment to another. If the patient’s interest and attention can be maintained long enough to ensure adequate testing, one finds that memory and learning ability are also impaired, in this way blending into the Korsakoff state. In response to the administration of thiamine, the patient rapidly becomes more alert and attentive and more capable of taking part in mental testing. If, however, the state is sustained, for some uncertain period, the most prominent abnormality becomes one of retentive memory (Korsakoff-amnesic state).

Drowsiness is a common feature of the Wernicke confusional state, but stupor and coma are rare as initial manifestations. If, however, the early signs of the disease are not recognized and the patient remains untreated, a progressive depression of the state of consciousness occurs with stupor, coma, and death in a matter of a week or two, just as occurred in Wernicke’s original cases. Autopsy series of Wernicke disease are heavily weighted with cases of the latter type, often undiagnosed during life (Harper; Torvik et al).

Some patients are alert and responsive from the time they are first seen and already show the characteristic features of the Korsakoff amnesic state. In a small number of such patients, the amnesic state is the only manifestation of the syndrome, and no ocular or ataxic signs (other than possibly nystagmus) can be discerned.

As indicated in Chap. 21, the core of the amnesic disorder is a defect in learning (anterograde amnesia) and a loss of past memories (retrograde amnesia). The defect in learning can be remarkably severe. The patient may be incapable, for example, of committing to memory the simplest of facts (such as the examiner’s name, the date, and the time of day) despite countless attempts; the patient can repeat each fact as it is presented, indicating that he understands what is wanted of him and that “registration” is intact, but by the time the third fact is repeated, the first may have been forgotten. However, certain nonverbal learning may take place; for example, with repeated trials, the patient may learn complex tasks such as mirror writing or how to negotiate a maze, despite no recollection of ever having been confronted with these tasks.

Anterograde amnesia is always coupled with a disturbance of past or remote memory (retrograde amnesia). The latter disorder is usually severe in degree, although not complete, and covers a period that antedates the onset of the illness by up to several years. A few isolated events and information from the past are retained, but these are related without regard for the intervals that separated them or for their proper temporal sequence. Usually the patient “telescopes” events into a brief period of time; sometimes the opposite occurs. This aspect of the memory disorder becomes prominent as the initial confusional stage of the illness subsides.

It is probably true that memories of the recent past are more severely impaired than those of the remote past (the rule of Ribot); language, computation, knowledge acquired in school, and all habitual actions are preserved. This is not to say that all remote memories are intact. As discussed in Chap. 21, these are not as readily tested as more recent memories, making the two difficult to compare. It is our impression that there are gaps and inaccuracies in memories of the distant past in practically all cases of the Korsakoff amnesic state, and serious impairments in many.

The cognitive impairment of the Korsakoff patient is not exclusively one of memory loss. Psychologic testing discloses that certain cognitive and perceptual functions that depend little or not at all on retentive memory are also impaired. As a rule, the Korsakoff patient has no insight into his illness and is characteristically apathetic and inert, lacking in spontaneity and initiative, and indifferent to everything and everybody around him. However, the patient has a relatively normal capacity to reason with data immediately before him.

Confabulation has generally been considered to be a specific feature of Korsakoff psychosis, but the validity of this view depends largely on how one defines confabulation, and there is no uniformity of opinion on this point. The observations of our colleague Victor and his colleagues (1959) do not support the oft-repeated statement that the Korsakoff patient fills the gaps in his memory with confabulation. In the sense that gaps in memory exist and that whatever the patient supplies in place of the correct answers fills these gaps, the statement is incontrovertible. It is hardly explanatory, however. The implication that confabulation is a deliberate attempt to hide the memory defect, out of embarrassment or for other reasons, is incorrect. In fact, the opposite seems to pertain: As the patient improves and becomes more aware of a defect in memory, the tendency to confabulate diminishes. Furthermore, confabulation can be associated with both phases of the Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome: The initial one in which profound general confusion dominates the disease, and the convalescent phase in which the patient recalls fragments of past experience in a distorted fashion. Events that were separated by long intervals are juxtaposed or related out of sequence, so that the narrative has an implausible or fictional aspect. In the chronic state of the disease, confabulation is usually absent. These and other aspects of confabulation are discussed fully in the monograph by Victor and colleagues (1959).

Approximately 15 percent of patients show signs of alcohol withdrawal, that is, hallucinations and other disorders of perception, confusion, agitation, tremor, and overactivity of autonomic nervous system function. These symptoms are evanescent in nature and usually mild.

Signs of peripheral neuropathy are found in more than 80 percent of patients with the Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome. In most, the neuropathic disease is mild and does not account for the disorder of gait, but it may be so severe and particularly painful that stance and gait cannot be tested. In a small number, retrobulbar optic neuropathy is added. Despite the frequency of peripheral neuropathy, overt signs of beriberi heart disease are rare. However, indications of disordered cardiovascular function such as tachycardia, exertional dyspnea, postural hypotension, and minor electrocardiographic abnormalities are frequent; occasionally, the patient dies suddenly following only slight exertion. These patients may show an elevation of cardiac output associated with low peripheral vascular resistance, abnormalities that revert to normal after the administration of thiamine. Postural hypotension and syncope are common findings in Wernicke disease and are probably a result of impaired function of the autonomic nervous system, more specifically to a defect in the sympathetic outflow (Birchfield). There may be mild hypothermia, loss of libido, and erectile dysfunction.

Patients with the Korsakoff amnesic state may have a demonstrably impaired olfactory discrimination. This deficit, like the notable apathy present in most Wernicke’s patients, is probably attributable to a lesion of the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus and its connections, and not to a lesion of the peripheral olfactory system (Mair et al). Vestibular function, as measured by the response to standard ice-water caloric tests, is universally impaired in the acute stage of Wernicke disease (Ghez), but vertigo is not a complaint. This vestibular paresis probably accounts for the severe disequilibrium in the initial stage of the illness.

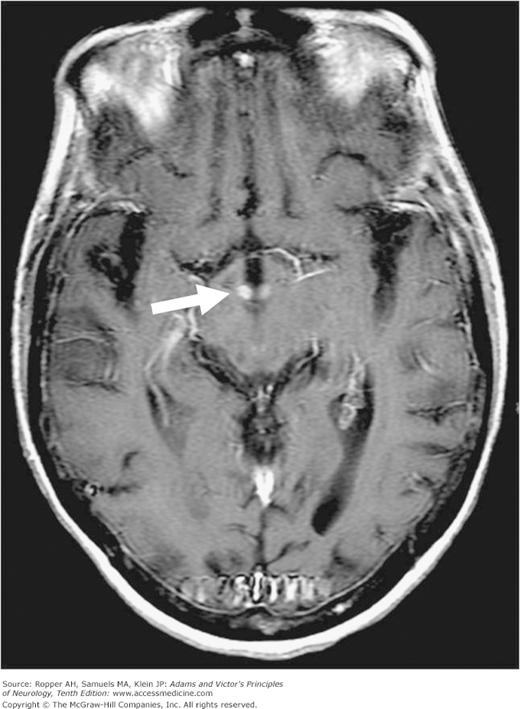

The acute lesions of the Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome in the mammillary bodies, and other medial thalamic and periaqueductal areas can be demonstrated in most cases by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Donnal et al; Varnet et al). The changes are most apparent on the fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), T2, and diffusion-weighted sequences (if there is hemorrhage), but they may also enhance as shown in Fig. 41-2. It is not clear to what extent gradient-echo MRI images can be expected to consistently reveal the small hemorrhagic lesions of the diencephalon and periventricular areas. Imaging is particularly useful in patients in whom stupor or coma has supervened or in whom ocular and ataxic signs are otherwise inevident (Victor, 1990), but in milder cases a normal MRI does not preclude the diagnosis. The typical MRI changes are observed in only 58 percent of cases according to Weidauer and colleagues. In the chronic state, the mammillary bodies may be shrunken if measured by volumetric techniques (Charness and DeLaPaz).

The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in uncomplicated cases of the Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome is normal or shows only a modest elevation of the protein content. Protein values greater than 100 mg/dL or a pleocytosis indicates the presence of a complicating illness such as subdural hematoma, meningeal infection, or encephalitis.

Measurements of serum thiamine and red blood cell transketolase have been explored as aids to diagnosis but are not sufficiently sensitive for clinical use and they are not readily available. Before treatment with thiamine, patients with Wernicke disease show a marked reduction in transketolase. Restoration of these values and of thiamine di- and triphosphate toward normal occurs within a few hours of the administration of thiamine, and completely normal values are usually attained within 24 h.

There are suggestions that there is a hereditary factor in the susceptibility of Wernicke-Korsakoff disease and possibly explains why only a small proportion of nutritionally deficient alcoholics develop this disease. Candidates for this variability have been proposed to be in transketolase activity or in the thiamine transporter gene, possibly on an epigenetic basis, but other genetic regions have been studied and to our reading, there is no clarity on this subject.

Approximately half of patients with Wernicke-Korsakoff disease show electroencephalographic (EEG) abnormalities, consisting of diffuse mild to moderate slow activity. Total cerebral blood flow and cerebral oxygen and glucose consumption may be reduced in the acute stages of the disease and may still be present after several weeks of treatment (Shimojyo et al). These observations indicate that significant reductions in brain metabolism need not be reflected in EEG abnormalities or in depression of the state of consciousness and that the latter is more a function of the location of the lesion than of the overall degree of metabolic defect.

The mortality rate in the acute phase of Wernicke disease was 17 percent in the series of patients collected by Victor, Adams, and Collins (1989) many decades ago. The fatalities were attributable mainly to hepatic failure and infection (pneumonia, pulmonary tuberculosis, and septicemia being at that time the most common). Some deaths were undoubtedly a result of the cerebral or cardiac effects of thiamine deficiency that had reached an irreversible stage.

Most patients respond in a fairly predictable manner to the administration of thiamine, as detailed further on. The most dramatic improvement is in the ocular manifestations. Recovery often begins within hours or sooner after the administration of thiamine and practically always within several days. This effect is so constant that a failure of the nystagmus and ocular palsies to respond to thiamine should raise doubts about the diagnosis of Wernicke disease. Horizontal nystagmus sometimes disappears in minutes. Sixth-nerve palsies, ptosis, and vertical gaze palsies recover completely within a week or two in most cases, but vertical nystagmus may sometimes persist for several months. Horizontal gaze palsies recover completely as a rule, but in 60 percent of cases a fine horizontal nystagmus remains as a permanent sequela. In this respect, horizontal nystagmus is unique among the ocular signs.

In comparison with the ocular signs, improvement of ataxia is delayed. Approximately 40 percent of patients recover completely from ataxia. The remaining recover incompletely or not at all and are left with a slow, shuffling, wide-based gait and inability to walk tandem. The residual gait disturbances and horizontal nystagmus provide a means of identifying obscure and chronic cases of dementia as alcoholic-nutritional in origin. Vestibular function improves at about the same rate as the ataxia of gait, and recovery is usually but not always complete.

The early symptoms of apathy, drowsiness, and global confusion invariably recede, and as they do the defect in memory and learning stands out more clearly. However, the memory disorder, once established, recovers completely or almost completely in only 20 percent of patients. The remainder is left with varying degrees of permanent Korsakoff amnesia.

It is apparent from the foregoing account that Wernicke disease and Korsakoff amnesia are not separate diseases, but that the ocular and ataxic signs and the transformation of the global confusional state into an amnesic syndrome are successive stages in a single disease process. Of 186 patients in the series of Victor, Adams and Collins (1989) who survived the acute illness, 157 (84 percent) showed this sequence of clinical events. As a corollary, a survey of alcoholic patients with Korsakoff amnesia in a psychiatric hospital disclosed that in most patients the illness had begun with the symptoms of Wernicke disease and that approximately 60 percent of them still showed some ocular or cerebellar stigmata of Wernicke disease many years after the onset. The same continuum cannot be invoked to explain alcoholic-nutritional cerebellar degeneration that arises as an independent illness and is not as a residual of the ataxia of Wernicke disease (see further on).

Patients who die in the acute stages of Wernicke disease show symmetrical lesions in the paraventricular regions of the thalamus and hypothalamus, mammillary bodies, periaqueductal region of the midbrain, floor of the fourth ventricle (particularly in the regions of the dorsal motor nuclei of the vagus and vestibular nuclei), and superior cerebellar vermis. Lesions are consistently found in the mammillary bodies and less consistently in other areas. The microscopic changes are characterized by varying degrees of necrosis of parenchymal structures. Within the area of necrosis, nerve cells are lost, but usually some remain; some of these are damaged but others are intact. Myelinated fibers are more affected than neurons. These changes are accompanied by a prominence of the blood vessels, although in some cases there appears to be a primary endothelial proliferation and evidence of recent or old petechial hemorrhage. In the areas of parenchymal damage there is astrocytic and microglial proliferation. Discrete hemorrhages were found in only 20 percent of Victor’s (1989) cases, and many appeared to be agonal in nature. The cerebellar changes consist of degeneration of all layers of the cortex, particularly of the Purkinje cells; usually this lesion is confined to the superior parts of the vermis, but in advanced cases the cortex of the most anterior parts of the anterior lobes is involved as well. Of interest is the fact that the lesions of Leigh encephalomyelopathy, a mitochondrial disorder implicating pyruvate metabolism, bear a resemblance to those of Wernicke disease but have a slightly different distribution and histologic characteristics.

The ocular muscle and gaze palsies are attributable to lesions of the sixth- and third-nerve nuclei and adjacent tegmentum, and the nystagmus to lesions in the regions of the vestibular nuclei. The latter are also responsible for the loss of caloric responses and probably for the gross disturbance of equilibrium that characterizes the initial stage of the disease. The lack of significant destruction of nerve cells in these lesions accounts for the rapid improvement and the high degree of recovery of oculomotor and vestibular functions. The persistent ataxia of stance and gait is caused by the lesion of the superior vermis of the cerebellum; ataxia of individual movements of the legs is attributable to an extension of the lesion into the anterior parts of the anterior lobes. Hypothermia, which occurs sometimes as an early feature of Wernicke disease, is probably attributable to lesions in the posterior and posterolateral nuclei of the hypothalamus (experimentally placed lesions in these parts have been shown to cause hypothermia or poikilothermia in monkeys).

The topography of the neuropathologic changes in patients who die in the chronic stages of the disease, when the amnesic symptoms are established, is much the same as the changes in the acute stages of Wernicke disease. Apart from the expected differences in age of the glial and vascular reactions, the only important difference has to do with the involvement of the medial dorsal and anterior nuclei of the thalamus. The medial parts of these nuclei were consistently involved in the patients who had shown the Korsakoff amnesic state during life; they were not affected in patients who had had no persistent amnesic symptoms in the series of Victor, Adams, and Collins (1989). The mammillary bodies were affected in all the patients, both those with the amnesic defect and those without. These observations suggest that the lesions responsible for the memory disorder are those of the thalami, predominantly of parts of the medial dorsal nuclei (and their connections with the medial frontal and temporal lobes and amygdaloid nuclei), and not those of the mammillary bodies, as is frequently stated. It is notable that the hippocampal formations, the site of damage in most other types of Korsakoff memory loss, are intact.

Wernicke disease constitutes a medical emergency; its recognition (or even the suspicion of its presence) requires the administration of thiamine. The prompt use of thiamine prevents progression of the disease and reverses those lesions that have not yet progressed to the point of fixed structural change. As emphasized earlier, in patients who show only ocular signs and ataxia, the administration of thiamine is crucial in preventing the development of an irreversible amnesic state.

Although 2 to 3 mg of thiamine may be sufficient to modify the ocular signs, much larger doses are needed to sustain improvement and replenish the depleted thiamine stores—initially, 50 to 200 mg intravenously and a similar dose mg intramuscularly—the latter being repeated each day until the patient resumes a normal diet. Certain writings indicate that initial doses of 500 mg are necessary to fully reverse the manifestations of Wernicke disease and prevent progression to the point of a Korsakoff syndrome. It appears that these higher doses, given for several days parenterally, are needed to replete vitamin levels in alcoholic and nutritionally deprived patients (see the articles by Thomson et al), but the need for high-dose regimens to reverse Wernicke disease is based on less-persuasive data. Nonetheless, current guidelines from the Royal College of Physicians, given by Thomson, promote high-dose regimens and seem advisable. The risks of administering parenteral thiamine have probably been overstated; anaphylactic reactions occurred in 0.1 percent of the series of Wrenn and colleagues and minor reactions in 1 percent.

To avoid precipitating Wernicke disease, it has become standard practice in emergency departments to administer 100 mg or more of thiamine in malnourished or alcoholic patients if intravenous fluids that contain glucose are being infused. Magnesium is given as well because it is required as cofactor for thiamine activity. It is similarly advisable to give B vitamins to alcoholic patients who are seen for other reasons in the emergency department so as to raise body stores of thiamine and other vitamins. The chronic alcoholic (or the nonalcoholic with persistent vomiting) exhausts thiamine in a matter of 7 or 8 weeks, during which time the administration of glucose may serve to precipitate Wernicke disease or cause an early form of the disease to progress rapidly. The further management of Wernicke disease involves the use of a balanced diet and all the B vitamins, as the patient is usually deficient in more than thiamine alone.

A different problem in management may arise once the patient has recovered from Wernicke disease and the amnesic syndrome becomes prominent. Only a minority of such patients (fewer than 20 percent in Victor’s series) recover entirely; moreover, the time of recovery may be delayed for several weeks or even months, and then it proceeds very slowly over a period of many months. The extent to which the amnesic symptoms will recover cannot be predicted during the acute stages of the illness. Interestingly, the alcoholic Korsakoff patient, once more or less recovered, seldom demands alcohol but will drink it if it is offered.

This designates an acute and frequently fatal disease of infants, which until recently was common in rice-eating communities of the Far East. It affects only breast-fed infants, usually in the second to the fifth months of life. Acute cardiac symptoms dominate the clinical picture, but neurologic symptoms (aphonia, strabismus, nystagmus, spasmodic contraction of facial muscles, and convulsions) have been described in many of the cases. This syndrome can be reversed dramatically by the administration of thiamine, so that some authors prefer to call it acute thiamine deficiency in infants. In the few neuropathologic studies that are available, changes like those of Wernicke disease in the adult have been described. Occasionally, there are outbreaks of this condition due to inadequately formulated baby foods that lack thiamine.

Infantile beriberi bears no consistent relationship to beriberi in the mother. Infants of mothers with overt signs of beriberi may be quite normal. The absence of beriberi in the mothers of affected infants suggests that infantile beriberi might be due to the result of a toxic factor in breast milk, but such a factor, if it exists, has never been isolated. The levels of thiamine in the breast milk of such mothers have not been measured, however.

Rarely, the clinical manifestations of beriberi in infancy represent an inherited (autosomal recessive) thiamine-dependent state, responding to the continued administration of massive doses of thiamine (Mandel et al; see also Table 41-3, further on).

Nutritional Polyneuropathy (Neuropathic Beriberi)

Most physicians in the Western world have only a dim notion about beriberi, which they recall as an ill-defined, predominantly cardiac disorder occurring among people whose diet was dominated by polished rice. The milling process, or “polishing,” removes the husk that contains most of the vitamin nutrients. In fact, beriberi is a distinct clinical entity that is not confined to any particular part of the world. Essentially, it is a disease of the heart and of the peripheral nerves (which may be affected separately), with or without edema, the latter feature providing the basis for the old division into “wet” and “dry” forms. The cardiac manifestations range from tachycardia and exertional dyspnea to acute and rapidly fatal heart failure, the latter being the most dramatic but uncommon manifestation of beriberi. Here we emphasize the peripheral neuropathy, or neuropathic beriberi.

That beriberi is essentially a disorder of the peripheral nerves was established in the late nineteenth century by the studies of the Dutch investigators Eijkman, Pekelharing and Winkler, and Grijns. Only after beriberi gained acceptance as a nutritional disease (this followed Funk’s discovery of vitamins in 1911) was it suspected that the neuropathy of alcoholics was also nutritional in origin. The similarity between beriberi and alcoholic neuropathy was commented upon by several authors, but it was Shattuck, in 1928, who first seriously discussed the relationship of the 2 disorders. He suggested that “polyneuritis of chronic alcoholism was caused chiefly by failure to take or assimilate food containing a sufficient quantity B vitamins and might properly be regarded as true beriberi.” Convincing evidence that “alcoholic neuritis” is not a result of the neurotoxic effect of alcohol was supplied by Strauss. He allowed 10 patients to continue their daily consumption of whiskey while they consumed a well-balanced diet supplemented with yeast and vitamin B concentrates; the peripheral nerve symptoms improved in every case. The observations made by Victor (1984) support Strauss’s contention that alcoholic polyneuropathy is essentially a nutritional disease.

The symptomatology of nutritional polyneuropathy is diverse. In fact, many patients are asymptomatic and evidence of peripheral nerve disease is found only by clinical or electromyographic examination. The mildest neuropathic signs are thinness and tenderness of the leg muscles, loss or depression of the Achilles reflexes and perhaps of the patellar reflexes and at times, a patchy blunting of pain and touch sensation over the feet and shins.

Most patients, however, are symptomatic and have weakness, paresthesias, and pain as the usual complaints. The symptoms are insidious in onset and slowly progressive, but occasionally they seem to evolve or to worsen rapidly over a matter of days. The initial symptoms are usually referred to the distal portions of the limbs and progress proximally if the illness remains untreated. The feet are always affected earlier and more severely than the hands. Usually some aspect of motor disability is part of the chief complaint, but in about one-third of the patients the main complaints are pain and paresthesias. It is this painful syndrome that has been the most prominent feature in the patients we have encountered in recent years. The discomfort takes several forms: a dull, constant ache in the feet or legs; sharp and lancinating pains, momentary in duration, like those of tabes dorsalis; sensations of cramping or tightness in the muscles of the feet and calves; or band-like feelings around the legs. Coldness of the feet is a common complaint but is not corroborated by palpation. Far more distressing are feelings of heat or “burning” affecting mainly the soles, less frequently the dorsal aspects of the feet. These dysesthesias fluctuate in severity and characteristically are worsened by contactual stimuli, sometimes to the point where the patient cannot walk or bear the touch of bedclothes, despite the relative preservation of motor power (allodynia). The term burning feet has been applied to this syndrome, but it is not particularly apt, as the patient also complains of other types of paresthesias, dysesthesias, and pain, and these symptoms may involve the hands as well as the feet.

Examination discloses varying degrees of motor, sensory, and reflex loss. As the symptoms suggest, the signs are symmetrical, and more severe in distal than in proximal portions of the limbs, and often confined to the legs. In some cases, the disproportionate affection of motor power may be striking, taking the form of a foot- and wrist-drop, but the proximal muscles are usually affected as well (indicated, for example, by climbing stairs or by difficulty in arising from a squatting position). In a few patients, the weakness appears to be most severe in the proximal muscles. Absolute paralysis of the legs had been observed in the past only rarely; immobility caused by contractures at the knees and ankles in neglected patients was a more common occurrence. Tenderness of muscles on deep pressure is a highly characteristic finding, elicited most readily in the muscles of the feet and calves. In the arms, tendon reflexes are sometimes retained despite a loss of strength in the hands. In patients in whom pain and dysesthesias are prominent and motor loss is slight, the reflexes at knee and ankle may be retained or even of greater than average briskness. This attests to the predominant affection of the small nerve fibers.

Excessive sweating of the soles and dorsal aspects of the feet and of the volar surfaces of the hands and fingers is a common manifestation of alcohol-induced nutritional neuropathy. Postural hypotension is sometimes associated, all symptoms indicative of involvement of the peripheral sympathetic nerve fibers.

Sensory loss or impairment may involve all the modalities, although one may be affected out of proportion to the others, usually pain and temperature. One cannot predict from the patient’s symptoms which mode of sensation might be affected disproportionately. In patients with impairment of superficial sensation (i.e., touch, pain, and temperature), the border between impaired and normal sensation is not sharp but shades off gradually over a considerable vertical extent of the limbs.

Patients in whom pain is the outstanding symptom do not constitute a distinct group in terms of their neurologic signs. Pain and dysesthesias may be prominent in patients with either severe or slight degrees of motor, reflex, and sensory loss. The term hyperesthetic is used commonly to designate the exquisitely painful form of neuropathy but is not well chosen; as pointed out in Chap. 8, one is usually able, by using finely graded stimuli, to demonstrate an elevated threshold to painful, thermal, and tactile stimuli in the “hyperesthetic” zone. Once the stimulus is perceived, however, it has a painful and diffuse, unpleasant quality (hyperpathia). Tactile evocation of pain or burning is an example, as mentioned, of allodynia.

In most patients with nutritional polyneuropathy, only the limbs are involved and the abdominal, thoracic, and bulbar muscles are usually spared; however, we have encountered 2 cases in which there was sensory loss in the pattern of an escutcheon over the anterior thorax and abdomen. In the most advanced instances of neuropathy, hoarseness and weakness of the voice and dysphagia as a result of degeneration of the vagus nerves may be added to the clinical picture.

Some idea of the incidence of the motor, reflex, and sensory abnormalities and the combinations in which they occur can be obtained from Table 41-1, which is based on Victor’s (1984) examination of 189 nutritionally depleted alcoholic patients. Noteworthy is the fact that only 66 (35 percent) of the 189 patients showed the clinical picture of polyneuropathy in its entirety, that is, a symmetrical impairment or loss of tendon reflexes, sensation, and motor power affecting legs more than the arms and the distal more than the proximal segments of the limbs. In the remaining patients, the motor-reflex-sensory signs occurred in various combinations.

NEUROPATHIC ABNORMALITY | LEGS (189 CASES) | ARMS (57 CASES) |

|---|---|---|

Loss of reflexes alone | 45 (24)a | 6 (10)b |

Loss of sensation alone | 10 (5) | 10 (18) |

Weakness alone | — | 5 (9) |

Weakness and sensory loss | 2 (1) | 10 (18) |

Reflex and sensory loss | 40 (21) | 2 (3) |

Sensory, motor, and reflex loss | 66 (35) | 17 (30) |

Data incomplete | 26 (14) | 7 (12) |

Stasis edema and pigmentation, glossiness, and thinness of the skin of the lower legs and feet are common findings in patients with any severe form of neuropathy. Major dystrophic changes, in the form of perforating plantar ulcers and painless destruction of the bones and joints of the feet (“Charcot forefeet”), have been described but are rare. Repeated trauma to insensitive parts and superimposed infection are thought to be responsible for the neuropathic arthropathy, as discussed in Chaps. 8 and 46.

The CSF is usually normal, although a modest elevation of protein content is found in a small number. Findings of nerve conduction studies include mild to moderate degrees of slowing of motor and sensory conduction and a marked reduction in the amplitudes of sensory action potentials; the motor conduction velocities in distal segments of the nerves may be reduced, while conduction in proximal segments is normal. Denervated muscles show fibrillation potentials in a pattern that is consistent with more severe involvement peripherally.

The essential change is one of axonal degeneration, with destruction of both axon and myelin sheath. Segmental demyelination occurs only in a small proportion of fibers. The most pronounced changes are observed in the distal parts of the longest and largest myelinated fibers in the crural and, to a lesser extent, brachial nerves. In advanced cases, the changes extend into the anterior and posterior nerve roots. The vagus and phrenic nerves and paravertebral sympathetic trunks may be affected in advanced cases. Anterior horn and dorsal root ganglion cells undergo chromatolysis, indicating axonal damage. Secondary changes in the posterior columns are seen in some cases.

The nutritional factor(s) responsible for the neuropathy of alcoholism and beriberi has not been defined precisely. Because of the difficulty in producing peripheral neuropathy in mammals by means of a thiamine-deficient diet, the idea that thiamine is the antineuritic vitamin was questioned in the past. Very few of the animal experiments undertaken to settle this point were satisfactory from a nutritional and pathologic point of view. Nevertheless, several studies in birds and humans do indeed indicate that uncomplicated thiamine deficiency may result in peripheral nerve disease. The necessity of either accepting or rejecting the specific role of thiamine became less urgent when it was demonstrated, in both animals and humans; a deficiency of pyridoxine or of pantothenic acid could also result in degeneration of the peripheral nerves (Swank and Adams).

The question of whether polyneuropathy in the alcoholic patient might be a result of the direct toxic effects of alcohol and not of a nutritional deficiency has been raised from time to time (see the preceding text and Denny-Brown and Behse and Buchthal). The evidence for this view is not compelling, either on clinical or on experimental grounds, as already mentioned (see reference to Strauss, in introductory section on nutritional neuropathy). The data presented more recently by Koike and colleagues, ostensibly in favor of the existence of a true alcoholic neuropathy, in our view present no convincing support of a direct toxic effect of alcohol. In the end, we view alcoholic–beriberi neuropathy as a multiple B-vitamin deficiency. The interested reader will find a detailed critique of this subject in the chapters by Victor and by Windebank in the second and third editions, respectively, of Peripheral Neuropathy, edited by Dyck and coworkers.

The first consideration is to supply adequate nutrition over a long period in the form of a balanced diet supplemented with B vitamins (equally important is to make certain that the patient follows the prescribed diet). If persistent vomiting or other gastrointestinal complications prevent the patient from eating, parenteral feeding becomes necessary; the vitamins may be given intramuscularly or added to intravenous fluids.

Where pain and sensitivity of the feet are the major complaints, the pressure of bedclothes may be avoided by placing a cradle support over the legs. Aching of the limbs may be related to their immobility, in which case they should be moved passively on frequent occasions. Aspirin or acetaminophen is usually sufficient to control hyperpathia and allodynia; occasionally codeine or methadone must be added. Obviously, opiates and addicting synthetic analgesics should be avoided if possible, but we have resorted to fentanyl patches for short periods in a few severely affected patients. Some of our patients with severe burning pain (similar to causalgia) in the feet had in the past been helped temporarily by blocking the lumbar sympathetic ganglia or by epidural injection of analgesics. The response to phenytoin, carbamazepine, and gabapentin has been inconsistent, but they are widely used. Adrenergic-blocking medication has been of little value and mexiletine, in our experience, of uncertain benefit.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree