Chapter 5 Readers of this chapter will be able to do the following: 1. Describe the distinction between language disorders and language differences. 2. Discuss the role of communication in culture. 3. List a range of assessment procedures for evaluating communication in children with cultural and linguistic differences. 4. Describe intervention issues and strategies for clients with cultural and language differences. 5. Discuss the role of the speech-language pathologist in addressing communicative competence in bilingual and bidialectical clients. In his book on the Civil War, James McPherson (1988) recounted an episode that occurred during General Lee’s surrender to General Grant at the Appomattox Courthouse. General Grant’s staff included a Native American of the Seneca tribe, by the name of Ely Parker. General Lee, upon being introduced to Parker, noticed Parker’s Native American features and remarked, “Well, it’s nice to see a real American here.” And Parker replied, “We are all Americans.” (p. 849) Unless you’ve been stranded on the space shuttle for the past decade, it must be obvious that the cultural composition of American society is changing. Sources of this change include an increase in immigration from Africa, Central and South American countries, the Caribbean Islands, and many parts of Asia and the Pacific Rim, as well as an increase in internal migration of Native Americans away from reservations toward metropolitan areas. A second source of the change is seen in the fact that, although the overall percentage of children in the United States is declining, the proportion of children from nonwhite, non-Western European, non−English-speaking backgrounds is increasing (Children’s Defense Fund, 1990; Hobbs & Stoops, 2002; U.S. Census, 2008). This is a result both of higher birth rates in non-European and non-American populations (National Center for Health Statistics, 1985) and of the higher number of females of child-bearing age in these groups, relative to the European and American populations (Hanson, 1998; Hobbs & Stoops, 2002). The result of these trends is that one in every four people in the United States is now of a race other than white. In some states, such as California and Texas, a majority of residents are of a non-European background. By the year 2050, it is predicted that the percentage of individuals from non-European backgrounds will increase, as the percentage of whites declines to slightly over half of the population (Goldstein & Iglesias, 2006). In some cities, such as Miami, Philadelphia, and Baltimore, “minority” children are a majority in the public schools (Adler, 1993; Brice, 2002). But as Goldstein and Iglesias (2006) point out, there is a misperception that individuals from culturally and linguistically diverse populations exist mainly in large, urban areas. Children from culturally and linguistically diverse populations are well represented across the nation’s school systems. In 2006–07, approximately 24% of all public school students attended schools where the combined enrollment of Black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, and American Indian/Alaska Native students was at least 75 percent, compared with 16 percent of public school students in 1990–91 (Planty et al., 2009), and 40% of children in U.S. schools were from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. The U.S. Department of Education estimates that 20% of students are learning English as a second language. And, unfortunately, a disproportionate number of these children will be from poor, single-parent (usually single-mother) families and at risk for a variety of disabilities (Battle, 2002b; Brice, 2002; Hanson, 2004; Iglesias, 2001), while only 6.9% of all speech-language pathologists (SLPs) are members of a racial minority, compared to 24.9% of the U.S. population (American Speech-Language and Hearing Association [ASHA], 2009). We should focus here for a moment on the distinction between a language difference and a language disorder. A disorder is what we defined in Chapter 1: a significant discrepancy in language skills relative to what would be expected for a client’s age or developmental level. A language difference, on the other hand, is a rule-governed language style that deviates in some way from the standard usage of the mainstream culture. Some children from culturally different backgrounds have language disorders. When they do, the SLP’s job is to provide remediation in a culturally sensitive way. But many children from culturally different backgrounds who are referred for language assessment do not have disorders, only limited exposure and experience with the language of instruction. Some, for example, who are acquiring English along with a home language display a different language acquisition pattern than children who are monolingual (Marian, 2009). Others may have limited exposure and opportunities to use English, so that their English skills are not as advanced as their skills in the home language. Roseberry-McKibbin (2008) discusses this issue in some detail and provides a framework for conceptualizing the needs of children with cultural and linguistic differences (CLD) who have varying levels of language ability and exposure to English. Table 5-1 provides an adaptation of her scheme. Table 5-1 Adapted from Roseberry-McKibben, C. (2008). Multicultural students with special needs. Oceanside, CA: Academic Communication Associates. Children can, of course, be at different stages along the road to being fully competent in English. Kohnert (2008) discussed the distinction between basic interpersonal communication skills (BICS) and cognitive academic language proficiency (CALP). These terms represent the two ends of a continuum of competence with a non-native language. Some English language learners (ELLs) will have limited English proficiency (LEP); they will have a hard time expressing very basic communicative functions in English (although they may do just fine in their home language). Some children will be at the BICS stage of English acquisition; they can use words that are frequent in the language, produce more or less grammatical sentences, and engage in everyday talk about familiar items and events. Cummins et al. (2006) estimates it takes a child 2 to 3 years of exposure to and experience with English to achieve BICS, although Roseberry-McKibben (2008) reports the time can actually vary widely across children. When they do achieve BICS, children may appear to be fluent speakers of English, and may be thought to be fully bilingual. But Hornberger and Cummins (2008), Kohnert (2008), and Roseberry-McKibben (2008) remind us that this level of language proficiency is often not enough to succeed in the classroom, especially after the primary grades. BICS gets a child by on the playground. But to be able to read higher level texts with adequate comprehension, produce a range of written discourse, use and understand subject-specific vocabulary, and engage in cognitively demanding communication, BICS is not enough. To achieve CALP, which enables these kinds of higher-level communication skills, takes much longer. Cummins et al. (2006) estimate at least 5 to 7 years and sometimes longer. Because BICS may make a child appear to speak English, yet does not support success in the academic curriculum, children at BICS levels of English skill may appear to have language-learning disorders. We’ll talk later about how to use assessment techniques to determine whether deficits in CALP represent language-learning difficulties or are rather a result of incomplete acquisition as seen in BICS. For now, it is important to know that the BICS/CALP distinction can make distinguishing language disorders from language differences challenging in ELLs. Still, one of the primary jobs of the SLP in dealing with children from CLD backgrounds is to accurately diagnose language disorders and distinguish them from language differences. When careful assessment, such as the kind described later in this chapter, reveals a difference rather than a disorder, Roseberry-McKibben (2008) suggests “sheltered English instruction.” In sheltered English instruction academic content is taught in English, but the input language is simplified and supports, including visual and graphic organizers, relating to students’ personal experiences, and supplementary culturally familiar materials are used (these supports are likely to help many students in the classroom, not only English language learners!). Kohnert et al. (2005) also discuss strategies for supporting the acquisition of home language of CLD children, as a solid foundation for the development of CALP skills. We’ll talk about developing both BICS and CALP levels of Standard English proficiency in the intervention section of this chapter. First, though, let’s look at few of the larger cultural groups likely to be encountered in language pathology practice with children. We’ll talk first about some information useful in understanding the communication patterns of children from some of these minority groups. Additional information is available in Roseberry-McKibbin (2008). Then we’ll look at some of the tools we can use to provide the most effective assessment and intervention services to these children. As Terrell and Jackson (2002) pointed out, African-Americans, currently almost 13% of the U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010), are not all alike. Some are wealthy, some are poor, and some are middle class. Socioeconomic class makes a good deal of difference in the attitudes and experiences of African-Americans, as it does in all Americans. However, one set of cultural experiences is common to many African-Americans: the history of forced abduction from their homelands, of slavery, and the tradition of racism and discrimination that has existed in the United States. Terrell and Terrell (1996) argued that the reaction to this set of experiences has formed many of the elements of contemporary African-American culture, including its music, religion, attitudes, and communication styles. Moreover, these experiences, according to Terrell and Terrell (1996), have led many African-Americans to develop a sense of cultural mistrust that can affect their performance on evaluations administered by white clinicians. Willis (2004) provides additional information on cultural features that were shaped by these experiences and are shared by families with African-American roots. The communication style shared by many, though not all African-Americans, is often called African American English, or AAE (Craig & Washington, 2006). AAE is considered a dialect of American English. Dialects are regional or cultural variations within a language that are used by a particular group of speakers. It shares many features with Standard American English (SAE; Craig and Washington, 2006). Dialects use a set of rules that are similar in many ways to those of the standard form of the language but differ in the frequency or circumstances of use of certain structures, lexical items, and other elements. All dialects of a language are mutually intelligible—any speaker of the language can understand them—and all are equally complex and legitimate (Burns et al., 2010). But some dialects have a higher status than others. The relative value or status of dialects is not inherent, though. It is said that a language can be defined as “a dialect with an army and a navy.” In other words, the choice of which dialect has the role of the “standard” form of the language has more to do with power relations within the society than with anything intrinsic to the linguistic structure of any of the dialects involved. Speaking a nonstandard dialect does not, in itself, constitute a disorder, but merely a difference in language use (Seymour, 2004). Still, the use of a nonstandard dialect such as AAE can in some situations be a handicap to the user, if speakers of the standard dialect view the nonstandard form as inferior or deviant (Fitts, 2001). Terrell and Terrell (1983), for example, found that when two groups of equally qualified African-American women applied for secretarial jobs advertised in newspapers, applicants who spoke AAE were less likely to be offered jobs. When they were, significantly lower salaries were offered to AAE speakers than to speakers of SAE. Prejudice against speakers of AAE, then, can have important economic implications. Not all African-Americans use AAE, and many who do are bidialectical. In addition, the degree to which dialectal features are present in the speech of AAE speakers varies (see the Dialect Density Measure by Craig, Washington, & Thompson-Porter, 1998). Some speakers, even as young as preschool age, use AAE, for example, at home and with friends and switch to SAE, or whatever the predominant regional dialect of the mainstream is, when operating in less familiar settings (Connor & Craig, 2006). Use of AAE varies, to some extent, with geographical region (Stockman, 2010). Washington and Craig (1992), for example, found that AAE speakers living in the urban Midwest did not use as many AAE changes in their phonology as did children from the South. The use of AAE changes over a person’s lifetime, as well (Craig & Washington, 2006). Craig, Thompson, Washington, and Potter (2003) and Issacs (1996) found that use of nonstandard dialect decreased through the elementary school grades, with the biggest dip occurring between kindergarten and first grade (Craig & Washington, 2006). AAE use also differs across contexts: Thomson, Craig, and Washington (2004a) found that African-American third graders used less AAE in more literate contexts, such as writing, than in picture description, while Curenton and Justice (2004) found that African-American preschool AAE speakers used literate language forms as often as Caucasian peers in a story-telling task from a wordless picture book. However, some African-Americans live in relatively isolated settings and may have little exposure to Standard English (Willis, 2004; Wolfram, Hazen, & Tamburro, 1997). Despite the great variability in its use (Burns et al., 2010), however, some characteristic differences between AAE and SAE are useful for clinicians to know. These differences are summarized in Box 5-1. For more detailed information on the linguistic structure of AAE, Charity (2008); Craig and Washington (2006); Green (2002); Mufwene, Rickford, Baugh, and Bailey (1998); Rickford (1999); and Roseberry-McKibben (2008) are excellent resources. Understanding these characteristics can help the clinician to communicate more effectively with African-American clients, to distinguish between a difference and a disorder, and to identify points of interference with achievement in the curriculum. It also is helpful in this enterprise to understand the normal sequence of acquisition in AAE, which is described in Craig and Washington (2002, 2005); Horton-Ikdard and Weismer (2005); Jackson and Roberts (2001); and Kamhi, Pollack, and Harris (1996). Americans of Hispanic heritage come from a variety of cultures and races. What they share is a background of Spanish-speaking ancestry, although they may not actually speak Spanish themselves. Hispanic-Americans (or Latinos) come from Mexico, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Spain, the Caribbean Islands, Central and South American countries, and even Asia or Africa, and account for 16% of the U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). This diverse group speaks many dialects of Spanish; the major five spoken in the United States are Mexican, Central American, Caribbean, Chilean, and Puerto Rican. Some Hispanics are monolingual Spanish speakers; others are bilingual, to one degree or another, in English and Spanish. Brice (2002), Goldstein (2001, 2004), Roseberry-McKibben (2002a), and Zuniga (2004) provide detailed information about many aspects of the Latino culture of these diverse peoples. Brice (2002); Brice and Brice (2007); Gildersleeve-Neumann, Kester, Davis, and Peña (2008); Haynes and Shulman (1998a); Kayser (2002); Scheffner Hammer, Miccio, and Rodriguez (2004); Tabors, Paez, and Lopez (2002); and Uccelli and Paez (2007) provide a detailed discussion of what is known about normal development of Spanish in children learning it as a first language. This information can be useful to clinicians attempting to differentiate between a language difference and a disorder in a child whose dominant language is Spanish. When looking at the Spanish language development of these children, comparing production to available information on normal acquisition of Spanish can help to establish the stage of development a child is demonstrating in the first language. We’ll talk in more detail later in the assessment section about some methods of looking at level of first language acquisition in children with LEP. In working with Hispanic children with LEP, some characteristic difficulties or interference points come up between English and Spanish in what we might call Spanish-influenced English (SpIE). These characteristics are summarized in Box 5-2. Hispanic children with LEP who make changes such as those listed in Box 5-2 in their use of English would not be considered as having a disorder. To determine whether a Hispanic child with LEP was having inordinate problems in learning English, we would need to look for other types of errors that would not be typical of SpIE. We’ll talk in more detail in the assessment section about methods of looking for these atypical kinds of errors. Joe and Malach (2004) reported that at the time of Christopher Columbus, there were at least 1000 Native American tribal entities, each with a distinct language, culture, set of beliefs, and governance structure. Even though many Native Americans have moved away from reservations to more urban areas, more than 1 million people still live on hundreds of reservations located in remote rural areas where medical, educational, and rehabilitative services are not readily available. Even Native Americans in cities share many of the cultural and child-rearing practices of their relatives on reservations (Joe & Malach, 2004; Westby & Vining, 2002). Like the other cultural groups being discussed, the Native American population encompasses great diversity. However, Joe and Malach (2004) and Robinson-Zanartu (1996) have pointed out some of the common themes among communication styles of the many first American peoples. Native American children from a variety of tribal groups have been found to score higher on motor, social, and self-help skills than their mainstream peers, although they score lower on language areas (Westby, 1986, 2005). These differences are thought to reflect the experience of the Native American children, whose cultures rely much more heavily on visual than on vocal channels of information exchange. Native American children are taught to learn by watching—being quiet, passive observers of cultural practices. Demonstration of skills to Native American children does not usually involve verbal accompaniment nor are children expected to show their knowledge by verbal performance. Instead, they are required to display their physical mastery of a task, such as dancing or weaving, by just doing it. Still, these cultural differences can have educational implications; children from Native American backgrounds are over-represented in special education (NCES, 2005), partly as a result of their tendency to “do” rather than talk. Basso (1979) reported that Apache children were scolded for “acting like a white man” if they talked too much. Native American children are taught that important questions deserve thoughtful answers and are encouraged to take time to consider a question carefully before answering. The long pauses they use before responding to questions are often misinterpreted as a processing problem or lack of knowledge of the correct answer. Similarly, Joe and Malach (2004) report that it is considered rude in many Native American cultures to ask too direct a question or to make direct eye contact with one in authority. Westby (1986) emphasized that a Native American child’s reluctance to speak, to look at the teacher, to ask questions, or a tendency to have long latency of response should not be misinterpreted as a lack of communicative competence. Instead, it should be understood as an appropriate expression of cultural patterns of communication (See Inglebret et al., 2008, for ways to use Native American storytelling traditions to encourage shared storybook reading). Robinson-Zanartu (1996) noted that many Native American languages do not have words for concepts such as hearing loss, retardation, or disability. Nichols and Keltner (2005) report that children so labeled by the mainstream culture may be considered as simply part of the traditional community by its members. This can have profound effects on the ways professionals need to communicate with families about assessment and intervention services. Reid (2000) and Westby and Vining (2002) identified several general differences that are commonly seen between English and Native American languages, and give some examples, primarily based on the Navajo language, as reported by Young (1967). These are summarized in Box 5-3. For more detailed and specific comparisons, clinicians will need to consult native speakers of the languages with which they come in contact, or resources such as Mithun (1999) and Patrick (2002). Again, in analyzing the language skills of a Native American child with LEP and attempting to decide whether a language difference or disorder exists, it will be necessary to determine whether the errors made in the child’s use of English are different or more pervasive than those of peers at similar stages of exposure to English. It also will be important to keep pragmatic differences in mind. Being sensitive to these differences will optimize the chances of obtaining information that is truly representative of the child’s communicative competence. Inglebret and Harrison (2005) offer general considerations to SLPs for working with Native Americans. Faircloth and Pfeffer (2008) talk about collaborating with tribal communities to provide early intervention services to Native American children. Since the 1980s many new immigrants to the U.S. have come from the Arab world of Middle-Eastern countries including Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Syria, Turkey, and Algeria. Ninety-two percent of this population is of the Muslim faith, but the Arab language also provides a bond among peoples of this region (Roseberry-McKibben, 2008). Middle Eastern communication styles include the acceptance of loud speech as normal in conversation, rapid speech, emphasis on eye contact as indicative of truthfulness in men, though less acceptable for women, acceptance of emotionality in conversation, and value placed on silence during communication. Arabic cultures place high esteem on poetry and eloquence, as well as on elaborate displays of respect through the use of titles in greetings (Omar Nydell, 2006). Some articulation and language differences between English and Arabic speakers are listed in Box 5-4. Children from Middle-Eastern background who make these kinds of errors will need additional opportunities to hear and use English, in order to refine their English-language skills.

Child language disorders in a pluralistic society

Defining language differences

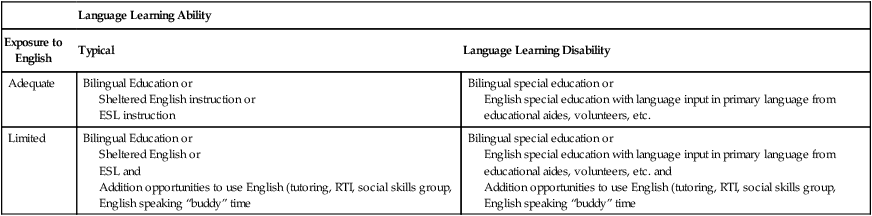

Language Learning Ability

Exposure to English

Typical

Language Learning Disability

Adequate

Bilingual Education or

Sheltered English instruction or

ESL instruction

Bilingual special education or

English special education with language input in primary language from educational aides, volunteers, etc.

Limited

Bilingual Education or

Sheltered English or

ESL and

Addition opportunities to use English (tutoring, RTI, social skills group, English speaking “buddy” time

Bilingual special education or

English special education with language input in primary language from educational aides, volunteers, etc. and

Addition opportunities to use English (tutoring, RTI, social skills group, English speaking “buddy” time

Larger minority groups in america’s cultures

African-american culture and communication

Hispanic-american culture and communication

Native american culture and communication

Arab-american culture and communication