Child psychiatry

Classification of psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents

Psychiatric assessment of children and their families

Psychiatric treatment for children and their families

Ethical and legal problems in child and adolescent psychiatry

Appendix: History taking and examination in child psychiatry

Introduction

The practice of child psychiatry differs from that of adult psychiatry in four important ways.

• Children seldom initiate the consultation. Instead, they are brought by a parent, or another adult, who thinks that some aspect of the child’s behaviour or development is abnormal. Whether a referral is sought depends on the attitudes and tolerance of these adults, and how they perceive the child’s behaviour. Healthy children may be brought to the doctor by over-anxious and solicitous parents or teachers, while in other circumstances severely disturbed children may be left to themselves.

• The child’s problems may reflect the problems of other people—for example, illness in the mother. Also, when a child’s problems have previously been contained within the family or school, that child may be referred when another problem, which reduces their capacity to cope with the child, arises in the family or school.

• The child’s stage of development must be considered when deciding what is abnormal. For example, repeated bed-wetting may be normal in a 3-year-old child but is abnormal in a 7-year-old. In addition, the child’s response to life events changes with age. Thus separation from the parents is more likely to affect a younger child than an older one.

• Children are generally less able to express themselves in words. For this reason, evidence of disturbance often comes from observations of behaviour made by parents, teachers, and others. These informants may give differing accounts, in part because children’s behaviour varies with their circumstances, and in part because the various informants have different ideas of what is abnormal. For this reason, informants should be asked for specific examples of any problem they describe, and asked about the circumstances in which it has been observed.

• The emphasis of treatment is different. Medication is used less in the treatment of children than in the treatment of adults, and is usually started by a specialist rather than the family doctor. Instead, there is more emphasis on working with the parents and the whole family, reassuring and retraining children, and coordinating the efforts of others who can help children, especially at school. Thus multidisciplinary working is even more important in child psychiatry than in adult psychiatry. Consequently, treatment is usually provided by a team that includes at least a psychiatrist, psychiatric nurses, a psychologist, and a therapist.

The first part of this chapter is concerned with a number of general issues concerning psychiatric disorder in childhood, including its frequency, causes, assessment, and management. The second part of the chapter contains information about the principal syndromes encountered in the practice of child psychiatry. The chapter does not provide a comprehensive account of child psychiatry. It is an introduction to the main themes for psychiatrists who are undertaking specialist general training. It is expected that they will follow it by reading a specialist text such as one of those listed under further reading on p. 680. Learning disability among children is considered in Chapter 23. Although this is a convenient arrangement, the reader should remember that many aspects of the study and care of children with learning disability are similar to those described in this chapter.

Normal development

The practice of child psychiatry calls for some knowledge of the normal process of development from a helpless infant into an independent adult. In order to judge whether any observed emotional, social, or intellectual functioning is abnormal, it has to be compared with the corresponding normal range for the age group. This section gives a brief and simplified account of the main aspects of development that concern the psychiatrist. A textbook of paediatrics should be consulted for details of these developmental phases (for example, see Hopkins et al., 2004).

The first year of life

This is a period of rapid development of motor and social functioning. Three weeks after birth, the baby smiles at faces, selective smiling appears by 6 months, fear of strangers by 8 months, and anxiety on separation from the mother shortly thereafter.

Bowlby (1980) emphasized the importance in the early years of life of a general process of attachment of the infant to the parents, and of more selective emotional bonding. Although bonding to the mother is most significant, important attachments are also made to the father and other people who are close to the infant. Other studies have shown the reciprocal nature of this process and the role of early contacts between the mother (or other carers) and the newborn infant in initiating bonding. Attachment and bonding are discussed further on p. 634.

By the end of the first year, the child should have formed a close and secure relationship with the mother or other close carer. There should be an ordered pattern of sleeping and feeding, and weaning has usually been accomplished. Children will have begun to learn about objects outside themselves, simple causal relationships, and spatial relationships. By the end of the first year, they enjoy making sounds and may say ‘mama’, ‘dada’, and perhaps one or two other words.

Year two

This too is a period of rapid development. Children begin to wish to please their parents, and appear anxious when they disapprove. They begin to learn to control their behaviour. By now, attachment behaviour should be well established. Temper tantrums occur, particularly if exploratory wishes are frustrated. These tantrums do not last long, and should lessen as the child learns to accept constraints. By the end of the second year the child should be able to put two or three words together as a simple sentence.

Preschool years (2–5 years)

This phase brings a further increase in intellectual abilities, especially in the complexity of language. Social development occurs as children learn to live within the family. They begin to identify with the parents and adopt their standards in matters of conscience. Social life develops rapidly as they learn to interact with siblings, other children, and adults. Temper tantrums continue, but diminish and should disappear before the child starts school. Attention span and concentration increase steadily. At this age, children are very curious about the environment and ask many questions.

In children aged 2–5 years, fantasy life is rich and vivid. It can form a temporary substitute for the real world, enabling desires to be fulfilled regardless of reality. Special objects such as teddy bears or pieces of blanket become important to the child. They appear to comfort and reassure the child, and help them to sleep. They have been called transitional objects.

Children begin to learn about their own identity. They realize the differences between males and females in appearance, clothes, behaviour, and anatomy. Sexual play and exploration are common at this stage. According to psychodynamic theory, at this stage defence mechanisms develop to enable the child to cope with anxiety arising from unacceptable emotions. These defence mechanisms have been described on p. 154.

Common problems in early childhood

In children from birth to the beginning of the fifth year, common problems include difficulties in feeding and sleeping, as well as clinging to the parents (separation anxiety), temper tantrums, oppositional behaviour, and minor degrees of aggression.

Middle childhood

By the age of 5 years, children should understand their identity as boys or girls, and their position in the family. They learn to cope with school, and to read, write, and begin to acquire numerical concepts. The teacher becomes an important person in children’s lives. At this stage children gradually learn what they can achieve and what their limitations are. Conscience and standards of social behaviour develop further. According to psychoanalytical theory, defence mechanisms develop further while psychosexual development is quiescent (the latent period). The latter notion has been questioned, and it now seems that in children aged 5–10 years sexual interest and activities are present, although they may be concealed from adults.

Common problems in middle childhood.

The common problems in this age group include fears, nightmares, minor difficulties in relationships with peers, disobedience, and fighting.

Adolescence

Adolescence is the growing-up period between childhood and maturity. Among the most obvious features are the physical changes of puberty. The age at which these changes occur is quite variable, usually between 11 and 13 years in girls, and between 13 and 17 years in boys. The production of sex hormones precedes these changes, starting in both sexes between the ages of 8 and 10 years. Adolescence is a time of increased awareness of personal identity and individual characteristics. At this age, young people become self-aware, are concerned to know who they are, and begin to consider where they want to go in life. They can look ahead, consider alternatives for the future, and feel hope and despair. Some experience emotional turmoil and feel alienated from their family, but such experiences are not universal.

Peer group relationships are important and close friendships often develop, especially among girls. Membership of a group is common, and this can help the adolescent in moving towards autonomy. Adolescence brings a marked increase in sexual interest and activity. At first, tentative approaches are made to the opposite sex. Gradually these become more direct and confident. In late adolescence, there is a capacity for affection towards the opposite sex as well as sexual feelings. How far and in what way sexual feelings are expressed depends greatly on the standards of society, the behaviour of the peer group, and the attitudes of the family.

Common problems in later childhood and early adolescence

Common problems among children aged from 12 to 16 years include moodiness, anxiety, minor problems of school refusal, difficulties in relationships with peers, disobedience and rebellion including truancy, experimenting with illicit drugs, fighting, and stealing. Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder may have their onset in this age group, but are uncommon.

Developmental psychopathology

In child psychiatry it is important to adopt a developmental approach for three reasons.

• The stage of development determines whether behaviour is normal or pathological. For example, as noted above bed-wetting is normal at the age of 3 years but abnormal at the age of 7 years.

• The effects of life events differ as the child develops. For example, infants aged under 6 months can move to a new carer with little disturbance, but children aged 6 months to 3 years of age show great distress when separated from the original carer, because an attachment relationship has been formed. After the age of 3 years, attachment bonds are still strong but the child’s ability to understand and to use language can reduce the effect of a change of caretaker provided that it is arranged sensitively.

• Psychopathology may change as the child grows older. Anxiety disorders in childhood tend to improve as the child develops, depressive disorders often recur and continue into adult life, conduct disorders frequently continue into adolescence as aggressive and delinquent behaviour, and also commonly as substance abuse—a problem that is less common in younger children. These changes and continuities are sometimes related as much to changes in the environment as to developmental changes in the child.

The psychopathology of individual disorders will be discussed later in the chapter. Here some general issues regarding childhood psychopathology are summarized.

The influence of genes. Susceptibility genes have been identified for a few disorders, namely autism, attention deficit disorder, and specific reading disorder. However, the amount of variance explained by the identified genes is not great, suggesting multiple genes of small effect, and interactions between genes and the environment. Also, genes may indirectly cause stressful life events–for example, they may control personality traits of irritability and impulsiveness that lead to the repeated breakdown of relationships.

The influence of the environment. Factors in the environment may predispose to or precipitate disorders, and they may maintain them. They may also protect from the effects of other causative agents—for example, the risk of depression in adulthood as a consequence of poor parental care in childhood is reduced by the experience of a caring relationship with another person. This experience is not protective against all causative factors—for example, a caring relationship does not reduce the risk of depression in adulthood following child abuse (Hill et al., 2001).

The dividing line between normal and abnormal. Many childhood disorders are at the extreme end of a continuum with normal behaviour. Despite this, we study them using a categorical system because decisions about treatment require ‘yes or no’ answers. To form a category, a cut-off point has to be decided, and this is usually rather arbitrary. Children who fall just below the cut-off point—and hence outside the diagnostic group—can nevertheless have problems and need help. For example, some adolescents who fall below the threshold for depressive disorder have significant psychosocial impairment, and even mild depressive symptomatology can be associated with poor academic performance (Pickles et al., 2001).

Continuities and discontinuities. Some symptoms and behaviour problems in childhood are associated with problems in adulthood. For example, overactivity and difficulties in management at the age of 3 years are associated with offending in adult life. In contrast, anxiety in childhood is less likely to persist into adulthood (see p. 661).

Parent–child interactions. Maternal behaviour affects the child, but children elicit behaviours from their parents. For example, a mother is likely to be less responsive to an infant who does not respond to cuddling and play than to a sibling who is responsive to her. Her lack of responsiveness may then affect the infant, thus increasing the difficulty with attachment.

Of course, most of these issues are also relevant to psychopathology in adults, and are considered further in Chapter 5.

Classification of psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents

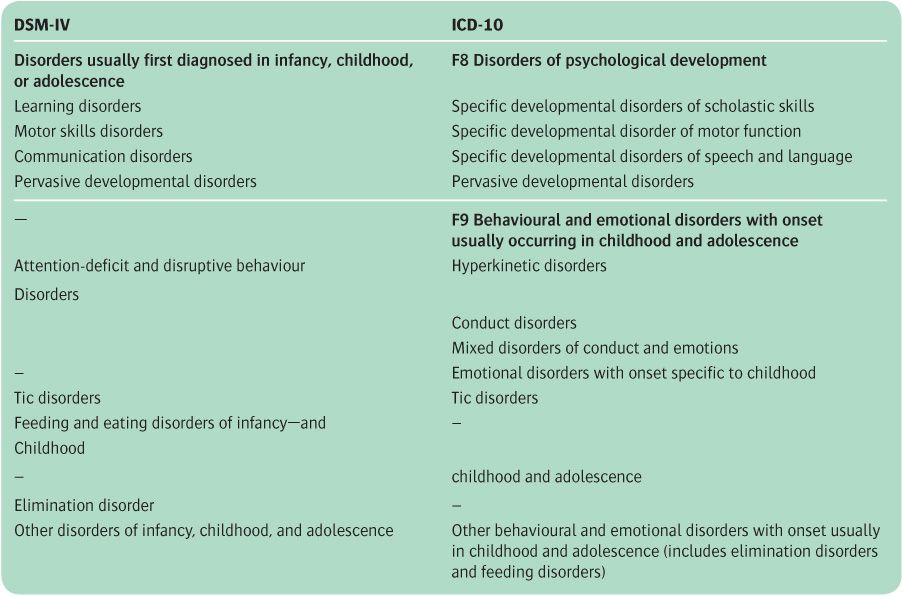

Both DSM-IV and ICD-10 contain a scheme for classifying the psychiatric disorders of childhood. Disorders of adolescence are classified partly with this scheme, and partly with the categories used in adult psychiatry.

Seven main groups of childhood psychiatric disorders are generally recognized by clinicians. The terms used in this book for the seven groups are listed below, with some alternatives shown in parentheses:

• adjustment reactions

• pervasive developmental disorders

• specific developmental disorders

• conduct (antisocial or externalizing) disorders

• attention-deficit hyperactivity disorders

• emotional (neurotic or internalizing) disorders

• symptomatic disorders.

Many child psychiatric disorders cannot be classified in a satisfactory way by allocating them to a single category. Therefore multi-axial systems have been proposed. ICD-10 has six axes:

1. clinical psychiatric syndromes

2. specific delays in development

3. intellectual level

4. medical conditions

5. abnormal social situations

6. level of adaptive functioning.

In DSM-IV, psychiatric syndromes and specific delays in development are both on axis 1, and the other axes are the same as in ICD-10, so that there are five in total. The scheme is easy to use, and allows clinicians to record systematically the different kinds of information required when categorizing children’s problems.

The DSM-IV and ICD-10 classifications for child psychiatric disorders are shown in Table 22.1. (In this book, learning disability (mental retardation) in childhood is considered in Chapter 23.) Both schemes are complicated, so only the main categories are shown in the table. In most ways the two schemes are similar. Both have categories for the following:

Table 22.1 Classification of childhood psychiatric disorders

• specific and pervasive developmental disorders, with the former divided into disorders affecting motor skills, speech and language (communication), and scholastic skills (learning)

• disorders of behaviour, which are divided into conduct (or disruptive behaviour) disorder and attention deficit (hyperkinetic) disorder

• anxiety (emotional) disorders (DSM-IV does not provide a separate category for childhood anxiety disorder, but uses the adult category instead)

• tic disorders.

DSM-IV has a category for eating and elimination disorders, whereas in ICD-10 these conditions are classified with sleep disorders under ‘other behavioural and emotional disorders.’ For further information about classification in child psychiatry, see Scott (2009a).

Epidemiology

Behavioural and emotional disorders are common in childhood. Estimates vary according to the diagnostic criteria and other methods used, but it appears that rates in different developed countries are similar. Moreover, the rates of emotional and behavioural disorders in developing countries are similar to those in developed ones. In the UK, the prevalence of child psychiatric disorder in ethnic-minority groups has usually been found to be similar to that in the rest of the population. The few exceptions are mentioned later in this chapter.

A landmark study was carried out more than 40 years ago on the Isle of Wight in the UK. The study was concerned with the health, intelligence, education, and psychological difficulties in all the 10- and 11-year-olds attending state schools on the island—a total of 2193 children (Rutter et al., 1970a). In the first stage of the enquiry, screening questionnaires were completed by parents and teachers. Children identified in this way were given psychological and educational tests and their parents were interviewed. The 1-year prevalence rate of psychiatric disorder was about 7%, with the rate in boys being twice that in girls. The rate of emotional disorders was 2.5%, and the combined rate of conduct disorders together with mixed conduct and emotional disorders was 4%. Conduct disorders were four times more frequent among boys than girls, whereas emotional disorders were more frequent in girls, in a ratio of almost 1.5:1. There was no correlation between psychiatric disorder and social class, but prevalence increased as intelligence decreased. It was also associated with physical handicap and especially with evidence of organic brain damage. In addition, there was a strong association between reading retardation and conduct disorder. A subsequent study using the same methods was conducted in an inner London borough (Rutter et al., 1975a,b). Here the rates of all types of disorder were twice those in the Isle of Wight.

Overall rates of psychiatric disorder. The results of these early studies have been broadly confirmed in subsequent investigations, using standard diagnostic criteria, conducted in the UK (Meltzer et al., 2000), in New Zealand (Fergusson et al., 1993), and in the Great Smoky Mountains in the USA (Costello et al., 1996). For example, in the study in the UK, ICD-10 disorders were present in about 10% of more than 10 000 children aged 5–15 years. The most common problem was conduct disorder (5%), closely followed by emotional disorders (4%), while 1% were rated as hyperactive. The less common disorders (autism, tic disorders, and eating disorders) were present in about 0.5% of the population.

Rates in adolescence. Evidence about adolescence was provided originally by a 4-year follow-up of the Isle of Wight study (Rutter et al., 1976b). At the age of 14 years, the 1-year prevalence rate of significant psychiatric disorder was about 20%. Prevalence estimates in subsequent studies vary somewhat, but most broadly confirm the original findings, with rates between 15% and 20%. However, there are some minor differences over time. In the UK, for example, there is evidence of a substantial increase in conduct and emotional problems in adolescents over the past two decades (Collishaw et al., 2004, 2010).

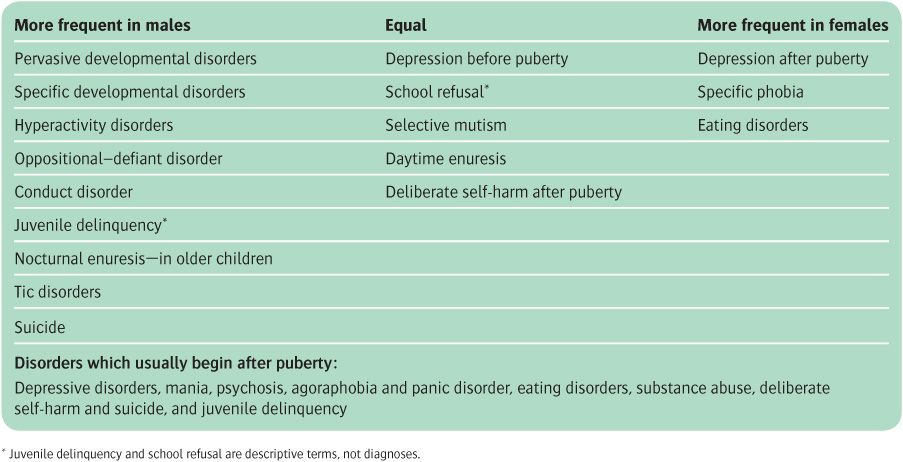

Variations with gender and age. Before puberty, disorders are more frequent overall among males than among females; after puberty, disorders are more frequent among females. Particular disorders also vary in frequency according to gender and age (see Table 22.2).

Table 22.2 Comparative frequency of psychiatric disorders in males and females

Other sources of variation. In the middle years of childhood, rates of psychiatric problems differ between areas of residence, being twice as high in urban areas (about 25%) as in rural areas (about 12%) (Rutter et al., 1975a). Subsequent studies have confirmed these earlier findings of a higher frequency of psychiatric disorder in association with:

• breakdown of the parental relationship, parental illness, and parental criminality

• residence in urban areas with social disadvantage

• attendence at a school with a high turnover of teachers.

Comorbidity. Studies using DSM criteria find high rates of comorbidity between childhood disorders. This could be because one disorder predisposes to another, or because they have common predisposing factors, or because the classification system has gone too far in identifying, as distinct disorders, patterns of behaviour that can occur in more than one condition.

For a review of the psychiatric epidemiology of childhood and adolescence, see Costello and Angold (2009).

Follow-up studies

Mild symptoms and behavioural or developmental problems are usually short-lived. However, conditions severe enough to be diagnosed as psychiatric disorders often persist for years. Thus in the Isle of Wight study, 75% of children with conduct disorder and 50% of those with emotional disorders at age 10 years were still handicapped by these problems 4 years later (Rutter et al., 1976b).

The prognosis for adult life of psychiatric disorder in childhood has been investigated in long-term studies. Robins (1966) followed up people who had attended a child guidance clinic 30 years previously, and compared them with a control group who had attended the same schools but had not been referred to the clinic. Children with conduct disorder had a poor outcome. As adults they were likely to develop antisocial personality disorder or alcoholism, have problems with employment or relationships, or commit offences. Some emotional problems that start in childhood also have a poor prognosis. Fombonne et al. (2001a,b) studied 149 people who, 20 years earlier, had attended a child and adolescent psychiatry clinic with a major depressive disorder, and some of whom also had a conduct disorder. Depression on the first occasion carried a high risk of adult depression, and comorbid conduct disorder on the first occasion carried an increased risk of drug dependence, alcoholism, and antisocial personality disorder in adulthood.

These examples show that continuities in psychiatric disorder between childhood and adulthood can be homotypic (where the same disorder persists over time) or heterotypic (where later disorders are of an apparently different kind). Although it is true that many young adult patients with psychiatric disorder have also had a diagnosable disorder in childhood or adolescence, childhood disorders do not invariably result in adult illness. For example, the majority of children with anxiety and depression do not have mood disorders in adulthood (Maughan and Kim-Cohen, 2005).

Aetiology

In discussing the causes of child psychiatric disorders, the principles are similar to those described in Chapter 5 on the aetiology of adult disorders. Most childhood disorders have multiple causes, with both genetic and environmental components. There is also a developmental aspect; children mature psychologically and socially as they grow up, and their disorders reflect this maturation. In the following paragraphs, four interacting groups of factors will be considered briefly. These are heredity, temperament, physical impairment with special reference to brain damage, and environmental factors in the family and society. All aspects of aetiology are discussed more fully in the textbook edited by Rutter et al. (2008).

Genetic factors

Children with psychiatric problems often have parents who suffer from a psychiatric disorder. Environmental factors account for a substantial part of this association. However, population-based twin studies indicate that there is a significant genetic contribution to some psychiatric disorders, especially to hyperactivity and anxiety disorders. Genetic studies are considered further when the aetiology of particular childhood psychiatric disorders is described later in this chapter. Here, we consider some general matters concerned with the interpretation of the results of genetic studies. Methods of genetic investigation are discussed on p. 98. Examples of genetic findings in child psychiatry are given at relevant points in this chapter, especially in the sections on autism and hyperactivity, where genetic research has produced some relevant findings (see p. 651). Some general points about the interpretation of genetic studies are shown in Box 22.1.

Temperament and individual differences

Many years ago, Thomas et al. (1968) conducted an influential longitudinal study in New York. They found that certain temperamental factors detected before the age of 2 years predisposed to later psychiatric disorder. In the first 2 years, one group of children (‘difficult children’) tended to respond to new environmental stimuli by withdrawal, slow adaptation, and an intense behavioural response. Another group (‘easy children’) responded to new stimuli with a positive approach, rapid adaptation, and a mild behavioural response. This second group was less likely than the first to develop behavioural disorders later in childhood. The investigators thought that these early temperamental differences were determined both genetically and by environmental factors.

More recent studies have confirmed an association between temperamental styles and subsequent childhood psychopathology. For example, behavioural inhibition predicts later anxiety disorders, while low positive affect has been linked to the development of depression. Perhaps unsurprisingly, children characterized by difficulties with self-control and high levels of irritability are more likely to be diagnosed subsequently with disruptive behaviour problems, including conduct disorder (Caspi and Shiner, 2008).

Brain disorder

Although serious physical disease of any kind can predispose to psychological problems in childhood, brain diseases are the most important. In the Isle of Wight study (see above), about 7% of physically healthy children aged 10–11 years were classified as having psychiatric problems, compared with about 12% of physically ill children of the same age, and 34% of children with brain disorders (Rutter et al., 1976b). The high prevalence in the latter group was not explained by the adverse social factors known to be associated with the risk of brain disorder. Nor is it likely to have been due to physical disability as such, because rates of psychiatric disorder are lower in children equally disabled by muscular disorders. Instead, the rate of psychiatric disorder among children with brain damage is related to the severity of the damage, although it is not closely related to the site. It is as common among brain-injured girls as boys, a finding which contrasts with the higher rate of psychiatric disorder among boys in the general population.

Children with brain injury are more likely to develop psychiatric disorder if they encounter adverse psychosocial influences of the kind that provoke psychiatric disorder in children without brain damage.

Maturational changes and delayed effects

The effects of brain lesions are more complex in childhood than in adult life because the brain is still developing. This has two consequences:

• Greater capacity to compensate. The immature brain is more able than the adult brain to compensate for localized damage. For example, even complete destruction of the left hemisphere in early childhood can be followed by normal development of language.

• Delayed effects. Early damage may not be manifested as a disorder until a later stage of development when the damaged area takes up some key function. It is well established that brain injury at birth may not result in seizures until many years later. It has been suggested that there may be similar delays in the behavioural consequences of brain injury.

Lateralized damage and psychopathology

The behavioural effects of lateralized brain damage are less specific in childhood than in adult life. Therefore attempts to explain, for example, educational problems in terms of left- and right-sided damage or dysfunction are of doubtful value, and attempts to use left-brain or right-brain training are unlikely to be helpful.

The consequences of head injury in childhood

Head injury is a common cause of neurological damage in childhood. The form of the consequent disorder is not very specific, partly because the effects of head injury are seldom localized to one area of the brain. Common consequences of severe injury are intellectual impairment and behaviour disorder. The former is proportional to the severity of the injury, but the relationship of behaviour disorder to the injury is less direct.

Epilepsy as a cause of childhood psychiatric disorder

The relationship between epilepsy and psychiatric disorder in adults is considered on pp. 338–43. In childhood there is a strong association between recurrent seizures and psychiatric disorder. As in adult life, the causal relationship may be of four kinds:

• the brain lesion causing the epilepsy may also cause the psychiatric disorder

• the psychological and social consequences of recurrent seizures may cause the disorder

• the effects of epilepsy on school performance may cause the disorder

• the drugs used to treat epilepsy may cause the disorder through their side-effects.

The site and the type of epilepsy appear to be generally less important, apart from the fact that temporal lobe epilepsy seems to be more likely to be associated with psychological disorder. The age of onset of seizures also determines the child’s response to epilepsy. For a review of the influence of brain injury and epilepsy on psycho-pathology, see Harris (2008).

Environmental factors

The effect of life events

The concept of life events (see p. 94) is useful in child psychiatry as well as adult psychiatry. Life events may predispose to or provoke a disorder, or protect against it. Events can be classified by their severity, their social characteristics (e.g. family problems, or the death of a parent), or their general significance—for example, exit events (i.e. separations) or entrance events (i.e. additions to a family by the birth of a sibling). The way in which stressful life events contribute to childhood psychiatric disorders is not well understood, but as in adults the psychological impact of such events is influenced by factors such as temperament, cognitive style, and previous life experience.

It is important to note that life events often occur in a setting of chronic stress which may itself play a causal role in the precipitation of psychiatric disorder. Also, in children as in adults, there are important differences in the liability of individuals to experience negative life events. This may be a reflection of societal factors such as poverty and discrimination, but the behaviour of individuals can also shape life experience in important ways. For example, children with conduct disorder have a substantially increased risk of experiencing negative life events (Sandberg and Rutter, 2008).

Family influences

As children progress from complete dependence on others to independence, they need a stable and secure family background with a consistent pattern of emotional warmth, acceptance, help, and constructive discipline. Prolonged separation from or loss of parents can have a profound effect on psychological development in infancy and childhood. Poor relationships in the family may have similar adverse effects, and overt conflict between the parents seems to be especially important.

Maternal deprivation and attachment

The much quoted work of Bowlby (1951) led to widespread concern about the effects of ‘maternal deprivation.’ Bowlby suggested that prolonged separation from the mother was a major cause of juvenile delinquency. Although this suggestion has not been confirmed, it was an important step towards his idea that attachment is a crucial stage of early psychological development. Attachments are formed in the second 6 months of life, and adaptive attachments are characterized by an appropriate balance between security and exploration. Bowlby proposed that infants derive, from their experiences of attachment, internal models of themselves, of other people, and of their relationships with others. He proposed further that these internal models persist through later childhood into adult life, and that they influence self-concept and relationships. Thus children whose caregivers are loving, sensitive to their child’s needs, and consistent in their responses are likely to grow up with self-esteem and able to form loving and trusting relationships.

Bowlby’s ideas have been generally supported by studies in which attachment has been measured in infancy and in later years. Attachment has usually been measured at around 6–18 months of age using the Strange Situations Procedure (Ainsworth et al., 1978), which evaluates the infant’s response to separation from, and subsequent reunion with, the mother or other attachment figure. In this test, the response to the initial separation appears to be determined more by temperament than by attachment, and it is the response to reunion that is used to measure attachment. Other measures of attachment have been developed for older children. Using such tests, attachments have been divided into four types:

• secure: present in about 60% of infants, and associated with caregiving that is sensitive and responsive to the child’s needs

• avoidant: present in about 15%, and associated with caregiving that is rejecting or intrusive

• disorganized: present in about 15%, and associated with caregiving that is unpredictable or frightening

• resistant–ambivalent: present in about 10%, and associated with caregiving that is inconsistent or lacking.

Studies of older children indicate that the type of attachment develops early in life and tends to be stable thereafter, although it is modified to some extent by changing life circumstances. Securely attached children generally do better than those with insecure attachments. Insecure attachments are associated not only with the factors mentioned above, but also with maternal depression, maternal alcoholism, and child abuse. Of the three types of insecure attachment, the disorganized type is the best predictor of future problems, especially externalizing problems.

The effect of separation. Bowlby’s original studies of the effects of separation on young infants have been broadly confirmed, but it has become clear that the effects depend on many factors, including:

• the age of the child at the time of separation

• the previous relationship with the carers

• the reasons for the separation

• how the separation was managed

• the quality of care during the separation.

For further information about attachment, see Goodman and Scott (2005), on which the above account is partly based.

Family risk factors

Family risk factors for psychiatric disorder in childhood are multiple and cumulative. The risk increases in children of families with severe marital or other relationship conflict, low social status, large size or overcrowding, paternal criminality, and parental psychiatric disorder. The risk is also increased in children who are placed in care away from the family.

Protective factors

Protective factors reduce the rate of psychiatric disorder associated with a given level of risk factors. Protective factors include good parenting, strong affectionate ties within the family, including good sibling relationships, sociability, and the capacity for problem solving in the child, and support outside the family from individuals, or from the school or church (Jenkins, 2008).

Child-rearing practices

Some patterns of child rearing are clearly related to psychiatric disturbance in the child, particularly those that involve verbal or physical abuse and scapegoating. Sexual abuse is another important risk factor (Glaser, 2008).

Effects of alternative childcare

Working mothers entrust part of the care of their children to other people. In general, the use of alternative childcare does not appear to be a major risk factor for psychiatric disorder, although multiple features of the nature of care need to be assessed. For example, high-quality care with sufficient individual attention can result in improved development of cognitive, social, and language skills. Generally, however, exposure to a large amount of alternative care correlates with increased levels of behavioural problems reported subsequently by teachers (Belsky et al., 2007).

Effects of parental mental disorder

Rates of psychological problems are higher in the children of parents with mental illness than in the children of healthy parents. These problems usually involve poor adjustment at home or at school, and often include disruptive behaviours. The causes are complex and are likely to be both genetic and environmental. However, an effect of illness in reducing the effectiveness of parenting has been demonstrated for depressed mothers, where attachment to the infant is impaired by lower levels of warmth and responsiveness. It also seems likely that maternal depression and anxiety during pregnancy can be associated with later childhood disturbance, independent of any postnatal effects of maternal illness (Jenkins, 2008).

Mothers who misuse alcohol or drugs. Children of such mothers suffer from a series of disadvantages which are related not only to the effects of drug taking on the development of the fetus and the mother’s care of the child, but also to features of the mother’s personality that led her to take drugs, and to social problems associated with the drug taking. For a review, see Greenfield et al. (2010).

Effects of divorce

The children of divorced parents have more psychological problems than the children of parents who are not divorced. It is not certain how far these problems precede the divorce and are related to conflict between the parents, the behaviour of one or both parents that contributed to the decision to divorce, and the changes in family relationships that accompany remarriage or cohabitation following the divorce. Distress and dysfunction in the children are greatest in the year after the divorce; after 2 years these problems are still present but are generally less severe than those of children who remain in conflictual marriages. For a review of the long-term effects of divorce on children, see Hetherington (2005).

Death of a parent

In children, the response to the death of a parent varies with age. Children aged below 4–5 years do not have a complete concept of death as causing permanent separation. Such children react with despair, anxiety, and regression to separation, however caused, and their reaction to bereavement is no different.

Children aged 5–11 years have an increasing understanding of death. They usually become depressed and overactive, and may show disorders of conduct. Some have suicidal thoughts and ideas that death would unite them with the lost parent. Suicidal actions are infrequent. In children over the age of 11 years, the response is increasingly like that of adults (see p. 171).

Bereavement may have long-term effects on development, especially if the child was young at the time of the parent’s death, and if the death was sudden or violent. Outcome probably depends largely on the effects of the bereavement on the surviving parent. Most studies of bereavement in children have been concerned with the death of a parent; few have concerned the death of a sibling. For a review, see Black and Trickey (2009).

Social and cultural factors

Although the family is undoubtedly the part of the child’s environment that has most effect on his development, wider social influences are also important, particularly as a cause of conduct disorder. In the early years of childhood, these social factors act indirectly through their influence on the patterns of family life. As the child grows older and spends more time outside the family, they have a direct effect as well. These factors have been studied by examining the associations between psychiatric disorder and type of neighbourhood and school.

Effects of neighbourhood

Rates of childhood psychiatric disorder are higher in areas of social disadvantage. For example, as already noted above (see p. 631), the rates of both emotional and conduct disorder were found to be higher in a poor inner-London borough than on the Isle of Wight. The important features of inner-city life may include lack of play space, inadequate social amenities for older children and teenagers, overcrowded living conditions, and lack of community involvement.

Effects of school

It has long been known that rates of child psychiatric referral and delinquency vary between schools. These differences persist when allowance is made for differences in the neighbourhoods in which the children live. It seems that children are less likely to develop psychiatric problems in a school in which teachers praise, encourage, and give responsibility to their pupils, set high standards, and organize their teaching well. Factors that do not seem to affect rates of psychiatric disorder include the size of the school and the age of its buildings.

Bullying is one of the stressful events that children may encounter at school. Goodman and Scott (2005, p. 243) have defined bullying as the repeated and deliberate use of physical or psychological means to hurt another child, without adequate provocation and in the knowledge that the victim is unlikely to retaliate effectively. It seems that around 2–8% of children are bullied once or more a week. They may be divided into a passive group, who are insecure and anxious and withdraw when attacked, and a provocative group, who are themselves aggressive either directly or by getting others into trouble. The bullies are more often boys than girls; boys are more likely to be physically aggressive, whereas girls are more likely to exclude their victims or campaign against them. Children who were bullied around the age of 5 years were found to exhibit a greater risk of emotional problems and disruptive behaviours at 2-year follow-up (Arseneault et al., 2006). Bullying in older children has important associations with self-harm, violent behaviour, and psychotic symptoms (Arseneault et al., 2010).

Psychiatric assessment of children and their families

The aims of assessment are to obtain a clear account of the presenting problem, to find out how this problem is related to the child’s past development and present life in its psychological and social context, and to plan treatment for the child and the family.

The psychiatric assessment of children differs in several ways from that of adults:

• A more flexible approach. With children it is often difficult to follow a set routine, so a flexible approach to interviewing is required, although it is still important that information and observations are recorded systematically.

• Interviewing of family members. Both parents or other carers should be asked to attend the assessment interview, and it is often helpful to have other siblings present.

• Information from schools. Time can be saved by asking permission to obtain information from teachers before the child attends the clinic. This information should be concerned with the child’s behaviour in school and their educational attainments.

Child psychiatrists vary in their methods of assessment. All agree that it is important to see the family together at some stage to observe how they interact. Some psychiatrists do this before seeing the patient alone, while others do it afterwards. It is generally better to see adolescent patients on their own before seeing the parents. With younger children the main informants are usually the parents, but children over the age of 6 years should usually be seen on their own at some stage. In the special case of suspected child abuse, the interview with the child is particularly important. Whatever the problem, the parents should be made to feel that the interview is supportive and does not undermine their confidence.

Interviewing the parents

Parents are likely to be anxious, and some fear that they may be blamed for their child’s problems. Time should be taken to put them at ease and explain the purpose of the interview. They should then be encouraged to talk spontaneously about the problems before systematic questions are asked. The methods of interviewing are similar to those used in adult psychiatry (see Chapter 3). The items to be included in the history are listed in the Appendix to this chapter. As in adult psychiatry, an experienced interviewer will keep the complete list in mind, while focusing on those items that are relevant to the particular case. It is important to obtain specific examples of general problems, to elicit factual information, and to assess feelings and attitudes.

Interviewing and observing the child

Because younger children may not be able or willing to express their ideas and feelings in words, observations of their behaviour and interaction with the interviewer are especially important. With very young children, drawing and the use of toys may be helpful. With older children, it may be possible to follow a procedure similar to that used with adults, provided that care is taken to use words and concepts appropriate to the child’s age and background. Standardized methods of observation and interviewing have been developed mainly for research purposes.

Starting the interview. It is essential to begin by establishing a friendly atmosphere and winning the child’s confidence, and asking what they like to be called. It is usually appropriate to begin with a discussion of neutral topics such as pets, favourite games, or birthdays, before turning to the presenting problem.

Techniques of interviewing. When a friendly relationship has been established, the child can be asked about the problem, their likes and dislikes, and their hopes for the future. It is often informative to ask what they would request if they were given three wishes. Younger children may be given the opportunity to express their concerns and feelings in paintings or play. Children can generally recall events accurately, although not always in the correct sequence. They are more suggestible than adults, and when asked a question are used to trying to give the answer that the adult has in mind—as they might, for example, in school. Therefore it is particularly important not to use leading questions when interviewing, and not to suggest actions or interpretations to a child who is being observed while painting or at play.

Behaviour and mental state. The items to be noted are listed in the Appendix to this chapter (see p. 680). Children who are brought to see a psychiatrist may appear silent and withdrawn at the first meeting; this behaviour should not be misinterpreted as evidence of depression.

Developmental assessments. By the end of the interview an assessment should have been made of the child’s stage of development relative to other children of the same age.

For further information and advice about interviewing and communicating with children, see Bostic and Martin (2009).

Interviewing the family

A family interview can contribute to the assessment of the interactions between family members, but it is not a good way to obtain factual information. The latter is generally more effectively obtained in interviews with the parents or other family members on their own. Of the various aspects of family interaction, the psychiatrist will usually be most interested in discord and disorganization, which are the features most closely associated with the development of psychiatric disorder. Patterns of communication between family members are also important.

It is usually best to see the family at the first assessment or soon after this, before the interviewer has formed a close relationship with the young patient, or with one of the parents, as this may make it more difficult to interview the other family members.

The interviewer could begin by asking ‘Who would be the best person to tell me about the problems?’ If one family member monopolizes the interview, another member should be asked to comment on what has been said. A useful question to stimulate discussion is ‘How do you think that your partner (daughter, son) would see the problem?’ The interviewer can then ask the partner (daughter, son) how they in fact see the problem. As an alternative, family members who are present can be asked what they think an absent member would think about the issues.

While observing the family’s ways of responding to these and other questions, the interviewer should consider the following:

• Who is the spokesperson for the family?

• Who seems most worried about the problem?

• What are the alliances within the family?

• What is the hierarchy in the family? For example, who is most dominant?

• How well do the family members communicate with one another?

• How do they seem to deal with conflict?

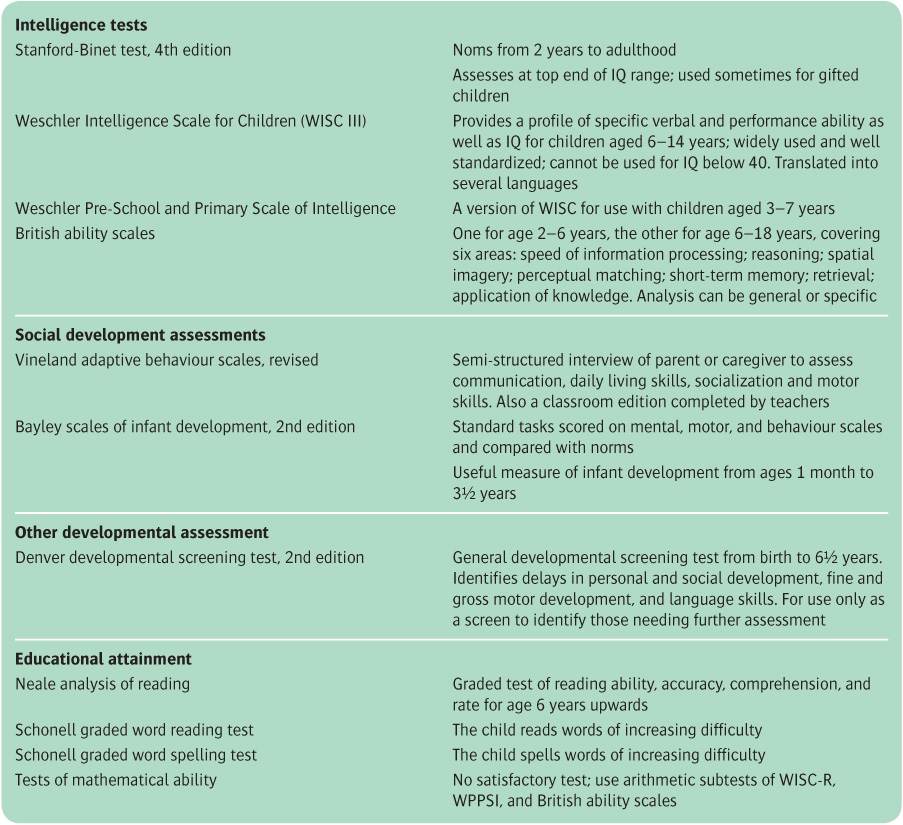

Psychological assessment

Measures of intelligence and educational achievement are often valuable. If mental development and achievement are inconsistent with chronological or mental age, or with the expectations of parents or teachers, this may indicate a generalized or specific disorder of development or may indicate a source of stress in disorders of other kinds. Some of the more commonly used procedures are listed in Table 22.3. For further information, see Charman et al. (2008).

Other information

The most important additional informants are the child’s teachers. They can describe classroom behaviour, educational achievements, and relationships with other children. They may also make useful comments about the child’s family and home circumstances. It is often helpful for a member of the psychiatric team to visit the home. This visit can provide useful information about material circumstances in the home, the relationship of family members, and the pattern of their life together.

Table 22.3 Notes on some psychological measures in use with children

Physical examination

If the child has not been examined recently by the general practitioner, an appropriate physical examination may be needed to complete the assessment. What is appropriate depends on the nature of the problem, but it will often be concerned with evidence of conditions that might affect the brain. Therefore the first step is to observe the child’s appearance, coordination, and gait, at rest and during play. A basic physical examination may follow, with emphasis on the nervous system. If abnormalities are found or suspected, the opinion of a paediatrician or paediatric neurologist may be needed.

Ending the assessment

At the end of the assessment the psychiatrist should explain to the parents—and to the child, in terms appropriate to their age—the result of the assessment and the plan of management. He should explain how he proposes to inform and work with the general practitioner, and seek permission to contact other people involved with the child, such as teachers or social workers. Throughout, the psychiatrist should encourage questions and discussion.

Formulation

As in adult psychiatry, a formulation is helpful when summarizing key issues. This has the same format as that used with adult patients (see p. 64). It starts with a brief statement of the current problem. The diagnosis and differential diagnosis are discussed next. Aetiology is then considered, with attention to predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating factors. The developmental stages of the child should be noted, as well as any particular strengths and achievements. An assessment of the problems and the strengths of the family is also recorded. Any further assessments should be specified, a treatment plan drawn up, and the expected outcome recorded.

Court reports

Psychiatrists may be asked to prepare court reports in relation to children. These reports are usually undertaken by specialists in child psychiatry; therefore only an outline will be given here. If general psychiatrists are required to prepare such a report, they should ensure that they are thoroughly aware of the relevant legislation, ask advice from a colleague with relevant special experience, and read a more detailed account of the requirements for court reports.

Courts concerned with children obtain evidence from several sources, including social workers, probation officers, community nurses, psychologists, and psychiatrists. In their reports, psychiatrists should focus on matters within their expertise, including:

• the child’s age, stage of development, and temperament, and the relevance of these to the case

• whether the child has a psychiatric disorder

• the child’s own wishes about their future, considered in relation to their age and understanding

• the parenting skills of the carers, how far they can meet the child’s needs, and other relevant aspects of the family.

While focusing on these matters, the psychiatrist should also be prepared to provide information about the following issues:

• the child’s physical, emotional, and educational needs

• the likely effect on the child of any possible change of circumstances (e.g. removal from home, or living with one or other parent after a divorce)

• any harm that the child has suffered or is likely to suffer.

The wishes of the child should be considered in relation to their age and ability to understand the present situation and possible future arrangements, and to relevant factors in the present situation—for example, some abused children maintain strong attachments to the abuser.

Parenting skills are judged partly on the basis of the history and reports of other people. They are also judged partly on direct observations of the interactions between the parents and the child, including the parents’ attachment to the child, their sensitivity to cues from the child, and their ability to meet the child’s needs.

The report is similar in structure to a court report for an adult, and is presented under the headings shown in Box 22.2.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree