3 Classification, aetiology, management and prognostic factors

Classification

Types of psychiatric disorder

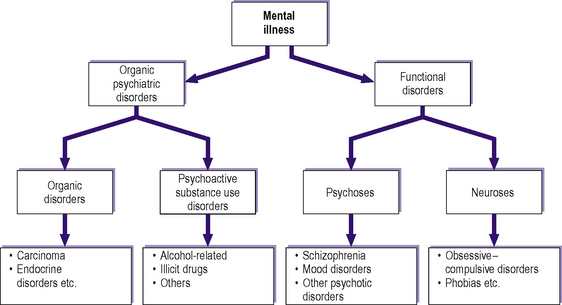

As shown in Figure 3.1, most psychiatric disorders can be divided into organic psychiatric disorders, which are secondary to known physical causes, and ‘functional’ disorders. As research in the neurosciences progresses, the underlying physical causes of the functional disorders are being discovered, for example at a neuronal, genetic and biochemical level. Therefore, it could be argued that the traditional dichotomy between organic and functional disorders is gradually becoming less appropriate.

Functional disorders

Psychoses

The major psychotic disorders are schizophrenia and mood disorders.

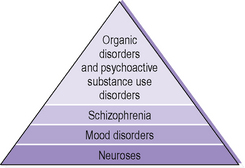

Diagnostic hierarchy

Figure 3.2 shows the diagnostic hierarchy used for the above types of disorder. The highest level in this hierarchy takes precedence over those below it when a diagnosis is being made. For example, if an otherwise well patient presents with symptoms seen in acute schizophrenia, which turn out to be secondary to intravenous amphetamine abuse, then the diagnosis is psychoactive substance use disorder and not schizophrenia. Similarly, if a patient with chronic schizophrenia has depressive symptoms, the diagnosis is schizophrenia rather than a mood disorder.

Aetiology

Chronological classification

A psychiatric disorder in a single patient can have multiple causes. These can usefully be classified chronologically into predisposing, precipitating and perpetuating factors for a given patient (Figure 3.3).

Individual causes

Psychiatric disorders usually have a multifactorial aetiology. Some individual causes include:

Note that in some cases, for example biochemical and endocrine factors, the changes may contribute to symptoms of the psychiatric disorder and/or may also be secondary to the disorder itself. Further details of the biopsychosocial approach are given in Chapters 1 and 2.

Management

Physical treatments

Antipsychotic drugs (neuroleptics)

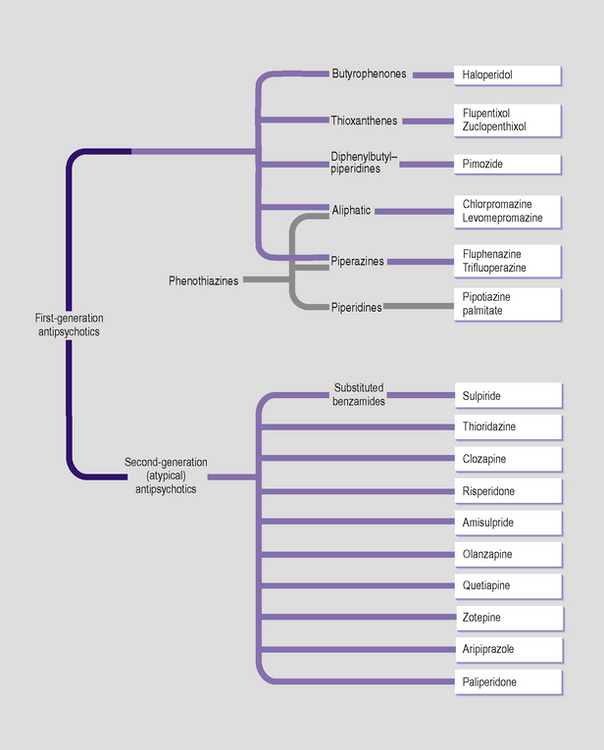

Antipsychotic drugs are also called neuroleptics. Their main uses are in the treatment of schizophrenia, the acute symptoms of mania and psychotic symptoms resulting from organic disorders and psychoactive substance use. Figure 3.4 shows a classification of some of the main antipsychotic drugs according to whether they are typical (conventional or first-generation) or atypical (second-generation).

Typical or first-generation antipsychotics

Details of these drug-induced movement disorders are given in Chapter 8.

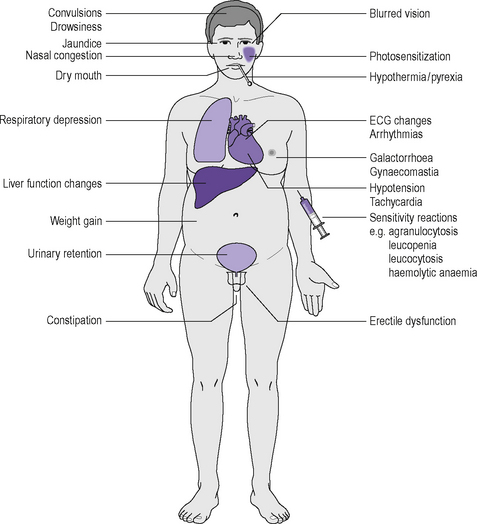

Other side-effects of chlorpromazine, the archetypal antipsychotic, are shown in Figure 3.5. Most of these side-effects also occur, in varying degrees, with other typical (first-generation) antipsychotics. Many of these side-effects are the result of antagonist action on the following neurotransmitters:

and requires urgent medical treatment. Between 0.5% and 1% of patients exposed to neuroleptics develop neuroleptic malignant syndrome. It can also occur with some non-neuroleptic drugs, such as tricyclic antidepressants.

Laboratory investigations commonly, but not always, show:

Typical antipsychotics are available in the form of slow-release depot preparations. These should be administered by deep intramuscular injection, usually at intervals of two to eight weeks. Their advantage over the oral forms is one of improved compliance. Examples of commonly administered depot preparations are given in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1 Commonly administered antipsychotic depot preparations

| First-generation antipsychotics |

| Flupentixol decanoate |

| Fluphenazine decanoate |

| Haloperidol decanoate |

| Pipotiazine palmitate |

| Zuclopenthixol decanoate |

| Second-generation antipsychotics |

| Risperidone |

Atypical or second-generation antipsychotics

Atypical or second-generation antipsychotics (see Figure 3.4) have a lower propensity to causeextrapyramidal symptoms (although, in general, they do have potential to cause tardive dyskinesia). This results from the fact that their primary action is not dopaminergic D2 receptor blockade, although most do bind to these receptors. Instead, they have a greater action than typical antipsychotics on other receptors, such as other dopaminergic receptors and serotonergic (5-HT) receptors. As with typical antipsychotics, neuroleptic malignant syndrome can occur with atypical antipsychotic treatment.

The archetypal atypical antipsychotic is clozapine, which has a higher potency than typical antipsychotics on 5-HT2, D4, D1, muscarinic and α-adrenergic receptors. Important side-effects of clozapine are neutropenia and potentially fatal agranulocytosis. As a result, patients taking this medication must undergo regular haematological monitoring. This should be weekly for the first 18 weeks and then at least fortnightly during the first year of treatment. After one year, if treatment with clozapine is continued and the blood count is stable, the haematological monitoring should be at least four-weekly. It should also be carried out four weeks after discontinuation. Clozapine treatment should be withdrawn permanently if the leucocyte count falls below 3000 mm–3 or the absolute neutrophil count falls below 1500 mm–3. Other side-effects are given in Table 3.2 and also include hypersalivation, ECG changes, impaired temperature regulation and hypertension.

Table 3.2 Side-effects of second-generation (atypical) antipsychotic drugs

| Weight gain, dizziness, postural hypotension (particularly during initial dose titration) |

| Hyperglycaemia and possibly type 2 diabetes mellitus (particularly with clozapine, olanzapine and risperidone). Therefore, body mass and plasma glucose should be monitored regularly |

| Neuroleptic malignant syndrome may occur rarely |

The atypical antipsychotic risperidone is indicated for psychoses in which both positive and negative symptoms (see Chapter 8) are prominent. Risperidone is an antagonist at 5-HT2A, 5-HT7, D2, α1– and α2-adrenergic and histamine H1 receptors, but not at cholinergic receptors. Side-effects are shown in Table 3.2 and also include gastrointestinal disturbances and hyperprolactinaemia (which may be associated with galactorrhoea, menstrual cycle changes, amenorrhoea and gynaecomastia). In order to avoidinitial orthostatic hypotension, treatment should begin with a three-day escalating dose titration: usually 2 mg in one to two divided doses on the first day, followed by 4 mg in one to two divided doses on the second day, with the usual dose range of 4–6 mg daily being achieved on the third day; a slower titration may be appropriate in some patients. The atypical antipsychotic paliperidone is a metabolite of risperidone. Risperidone is the first second-generation (atypical) antipsychotic to be made available in the form of a long-acting depot injection (see Table 3.1).

The atypical antipsychotic quetiapine is indicated for the treatment of both positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. It has a higher affinity for cerebral 5-HT2 receptors than for cerebral D1 and D2 receptors. It also has high affinity for histaminergic and α1-adrenergic receptors, but not for cholinergic receptors. As it may cause QT interval prolongation, quetiapine should be used with caution in patients with cardiovascular disease. Other side-effects are outlined in Table 3.2.

The atypical antipsychotic olanzapine is effective in maintaining the clinical improvement during continuation therapy in patients who respond to initial treatment. Olanzapine has a similar structure to clozapine. It has a binding affinity to D2 receptors that is less than that of typical antipsychotics but greater than that of clozapine. It is an antagonist at several 5-HT receptor subtypes (including 5-HT2A/2C, 5-HT3 and 5-HT6), and α1– and α2-adrenergic, histamine H1 and muscarinic receptors. Side-effects are given in Table 3.2.

The atypical antipsychotic amisulpride is indicated for the treatment of both positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. It is a highly selective antagonist at D2 and D3 receptors, and therefore produces mild extrapyramidal side-effects and hyperprolactinaemia, which may manifest as galactorrhoea, amenorrhoea, gynaecomastia, breast pain and sexual dysfunction. Other side-effects are given in Table 3.2.

Aripiprazole has high affinity for D2 (as a partial agonist), D3, 5-HT1A (as a partial agonist) and 5-HT1B receptors. Side-effects are given in Table 3.2.

Zotepine has a molecular structure similar to that of clozapine. It has high affinity for 5-HT2A receptors. Before treatment and each time the dose of zotepine is increased, the patient’s plasma electrolytes and ECG (to check for QT interval prolongation) should be monitored. Other side-effects are given in Table 3.2.

Antimuscarinic drugs used in parkinsonism

When antipsychotic drug treatment causes parkinsonian symptoms, these may be amenable to treatment with antimuscarinic (anticholinergic) drugs (see Table 3.3).

Table 3.3 Antimuscarinic drugs used in the treatment of parkinsonism resulting from pharmacotherapy with antipsychotics

| Procyclidine |

| Trihexyphenidyl (benzhexol) |

| Orphenadrine |

The use of these drugs is discussed further in Chapter 9.

Lithium

Lithium salts are used in the:

Side-effects are shown in Figure 3.6. Oedema should not be treated with diuretics because thiazide and loop diuretics reduce lithium excretion and so could cause lithium intoxication. Figure 3.7 shows signs of lithium intoxication. At plasma levels of above 2 mmol L–1 the following effects can occur:

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree