18 Eating disorders

Eating disorders traditionally include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, obesity and psychogenic vomiting. In the USA over recent years ‘binge eating disorder’ has been added to this list. There has also been more interest in the feeding disorders of infancy (see Chapter 16). These conditions have evoked intense medical interest because they exemplify the interaction between psychological and somatic symptomatology.

Definitions and diagnostic criteria

The ICD-10 and DSM-IV-TR requirements for diagnoses of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are shown in Table 18.1. Although anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are distinguished in ICD-10, the other diagnoses of ‘atypical anorexia nervosa’ and ‘atypical bulimia nervosa’ recognize that it is by no means agreed that they are distinct entities. In ICD-10 it is noted that patients with anorexia nervosa can progress to bulimia nervosa and vice versa. The situation is further confused by the suggestion by some researchers that it is appropriate to distinguish between patients with anorexia nervosa who maintain a low weight by restricting caloric intake (‘restrictors’) and those who use restriction together with the symptoms also seen in bulimia nervosa (vomiting, purging, excessive exercise, use of appetite suppressants and/or diuretics).

Table 18.1 ICD-10 and DSM-IV-TR classifications of eating disorders

| ICD-10 criteria for eating disorder (F50) |

| F50.0 Anorexia nervosa |

| F50.1 Atypical anorexia nervosa |

| F50.2 Bulimia nervosa |

| F50.3 Atypical bulimia nervosa |

| F50.4 Overeating associated with other psychological disturbances |

• Obesity from overeating as a reaction to stressful events where the overeating is the predominant symptom |

| F50.5 Vomiting associated with other psychological disturbances |

| DSM-IV-TR classification for eating disorder (307) |

| 307.1 Anorexia nervosa Specify type: Restricting type; binge eating/purging type |

| 307.51 Bulimia nervosa Specify type: Purging type/non-purging type |

| 307.50 Eating disorder NOS |

| Research criteria for binge eating disorder (classified under 307.50 above): |

NOS, not otherwise specified.

Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa

Clinical features

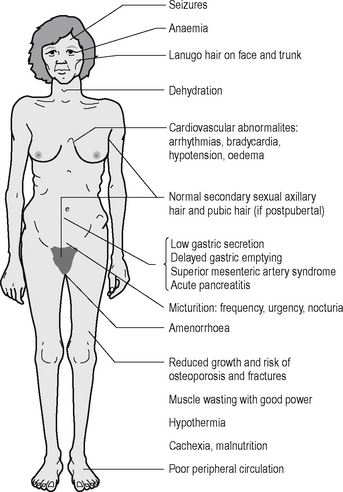

With dieting and progressive weight loss, apart from increasing cachexia, various bodily changes occur as a direct result (Figure 18.1). Profound effects on hormonal balance return hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal hormones to a prepubertal pattern. In prepubertal patients menarche is delayed. Effects on growth hormones produce a slowing or cessation of normal growth. If low weight is maintained for long enough, then final height may be stunted.

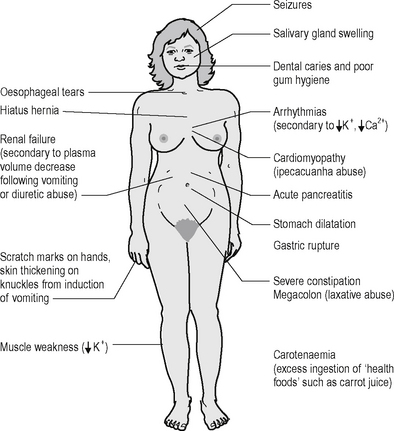

In bulimia nervosa, extra medical complications occur in relation to the vomiting, purging and/or use of diuretics (Figure 18.2).

Low mood is very prominent in patients with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, particularly at low weight in the former. The symptoms can include the full biological array of symptoms (see Chapter 9), including sleep loss as mentioned above. In the majority of cases, the low mood resolves with return to normal weight. It must be noted that suicidal ideation and behaviour can occur in the context of this low mood. In bulimia nervosa, suicidal attempts and self-mutilation can be significant features.

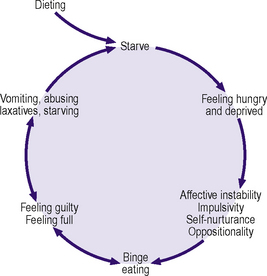

In bulimia nervosa, there is often a history of anorexia nervosa, and occasionally anorexia nervosa can be preceded by bulimic-type symptomatology. A typical cycle in bulimia nervosa is shown in Figure 18.3. It must be noted that there are very prominent psychological triggers and perpetuating factors that maintain the cycle.

Figure 18.3 • Typical cycle in bulimia nervosa.

(After Garfinkel PF, Garner DM 1982 Anorexia nervosa: a multidimensional perspective. Brunner Mazel, New York.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree