9 Mood disorders, suicide and parasuicide

Introduction

As discussed in Chapter 5, the terms affect and mood have different meanings, although both refer to emotional states. Definitions based on the DSM are:

The disorders of mood discussed in this chapter are depressive episodes, bipolar disorder and persistent mood disorders. Schizoaffective disorders are discussed in Chapter 8, whereas anxiety disorders, which can be considered to be disorders of emotion, are described in Chapter 10. Table 9.1 gives the ICD-10 classification of the mood disorders.

Table 9.1 ICD 10 classification of mood (affective) disorders

| F30 Manic episode |

| F31 Bipolar affective disorder |

| F32 Depressive episode |

| F33 Recurrent depressive disorder |

| F34 Persistent mood (affective) disorders |

| F38 Other mood (affective) disorders |

| F39 Unspecified mood (affective) disorder |

Depressive episode

Clinical features

In depressive episodes there is depression of mood and:

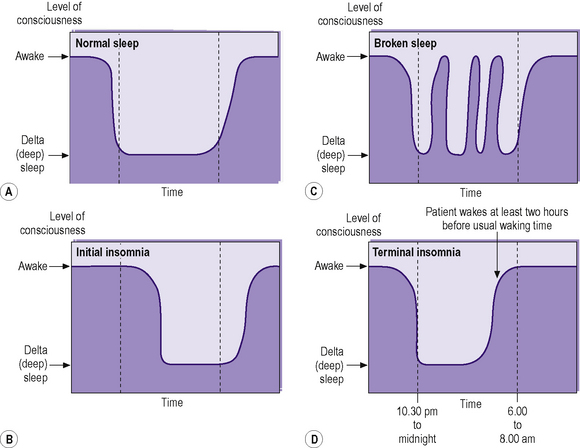

Depressive episodes frequently cause somatic or physiological changes. These are known as biological symptoms of depression and are summarized in Table 9.2. Reduced appetite leads to weight loss, which is often taken as meaning a loss of at least 5% of body weight in a month. Constipation is also a common feature of depressive episodes. Compared with normal sleep (Figure 9.1), the following types of insomnia may occur:

Table 9.2 Biological symptoms of depression

| Reduced appetite |

| Reduced weight |

| Constipation |

| Early morning wakening (terminal insomnia) |

| Diurnal variation of mood |

| Reduced libido |

| Amenorrhoea |

Mental state examination

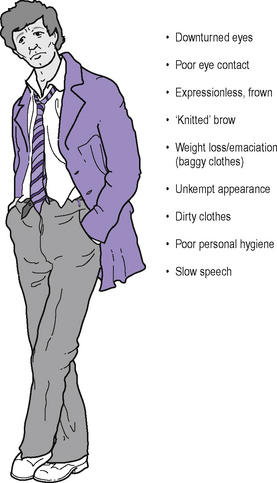

Appearance (Figure 9.2). Depressive facies typically include downturned eyes, sagging of the corners of the mouth and, often, the presence of a vertical furrow between the eyebrows. The patient usually makes poor eye contact with the interviewer. There may be direct evidence of weight loss, with the patient appearing emaciated and perhaps dehydrated. Indirect evidence of recent weight loss may be clothes appearing to be too large. Evidence of poor self-care and general neglect may include an unkempt appearance, poor personal hygiene and dirty clothing.

Behaviour. Psychomotor retardation typically occurs.

Speech. This is slow, with long delays before answering questions.

Cognition. Poor concentration may lead the patient to think (mistakenly) that memory is also impaired. In elderly patients the presentation of depression may be very similar to that of dementia; this is known as (depressive) pseudodementia (see Chapter 20).

Depressive stupor

The patient exhibits features of stupor, being unresponsive, akinetic, mute and fully conscious. (Details of the differences between depressive stupor and neurological stupor are given in Chapter 5.) Following an episode of stupor the patient can recall the events that took place and the depressed mood at the time. Episodes of excitement may take place between episodes of stupor. Owing to effective treatment regimens now available, depressive stupor is only rarely seen.

Masked depression

Depressed patients may not always present with a depressed mood, but may instead present with somatic or other complaints. They may somatize their depressed mood owing to cultural factors (see Chapter 19), or indeed may not be able to articulate their emotions, as in the case of patients with severe learning disability (see Chapter 17) and elderly patients with dementia (see Chapter 20). In such cases, the presence of biological symptoms of depression is particularly helpful in making the diagnosis. In the case of learning disability, diurnal variation in abnormal behaviour may be observed and mirror diurnal variation in mood. The effective treatment of masked depression usually leads to a resolution of the somatic or other presentations.

Other types of depression

Agitated depression can occur in the elderly and is considered in Chapter 20. Neurotic depression or dysthymia is considered below. Another neurotic disorder, known as mixed anxiety and depressive disorder or anxiety depression, in which both anxiety and depressed mood are present but neither is clearly prominent, is considered in Chapter 10.

Investigations

The investigations carried out in a patient presenting for the first time with depressive symptomatology are those described in Chapter 5, and include:

In the case of first presentation with auditory hallucinations in the elderly, i.e. when a differential diagnosis being considered is paraphrenia (see Chapter 20), tests of hearing and vision should be carried out at an early stage, as sensory deprivation is an important cause in this age group.

Differential diagnosis

Organic disorders and psychoactive substance use disorders should be excluded before making a diagnosis of a depressive episode. These are described in Chapters 6 and 7. A full physical examination and appropriate further investigations (see above) should be carried out, particularly in a case of first presentation, to exclude such disorders.

Aetiology

The aetiology of depressive episodes is considered in the section on bipolar disorder.

The reasons for the increased prevalence of depressive episodes in women compared with men are not known, but the following possibilities have been suggested (see also Chapter 12):

Management

Physical treatments

Pharmacotherapy. The mainstay of physical treatment is antidepressant medication. As detailed in Chapter 3, there are now available many antidepressants which are relatively safe in overdose, such as those belonging to the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (NARI), reversible inhibitor of monoamine oxidase A (RIMA) and noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant (NaSSA) groups. (There is some evidence that many antidepressants may actually be only marginally more effective than placebos in treating depression. The reader is referred to the excellent book by Professor Irving Kirsch (see Further reading). It may not be a good idea to mention this in psychiatry examinations though.) Certain antidepressants, particularly SSRIs, may actually increase the risk of suicide. The 58th edition (2009) of the British National Formulary (BNF) warns: ‘The use of antidepressants has been linked with suicidal thoughts and behaviour; children, young adults, and patients with a history of suicidal behaviour are particularly at risk. Where necessary, patients should be monitored for suicidal behaviour, self-harm, or hostility, particularly at the beginning of treatment or if the dose is changed.’

It may be considered in severe depression associated with:

Prognosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree