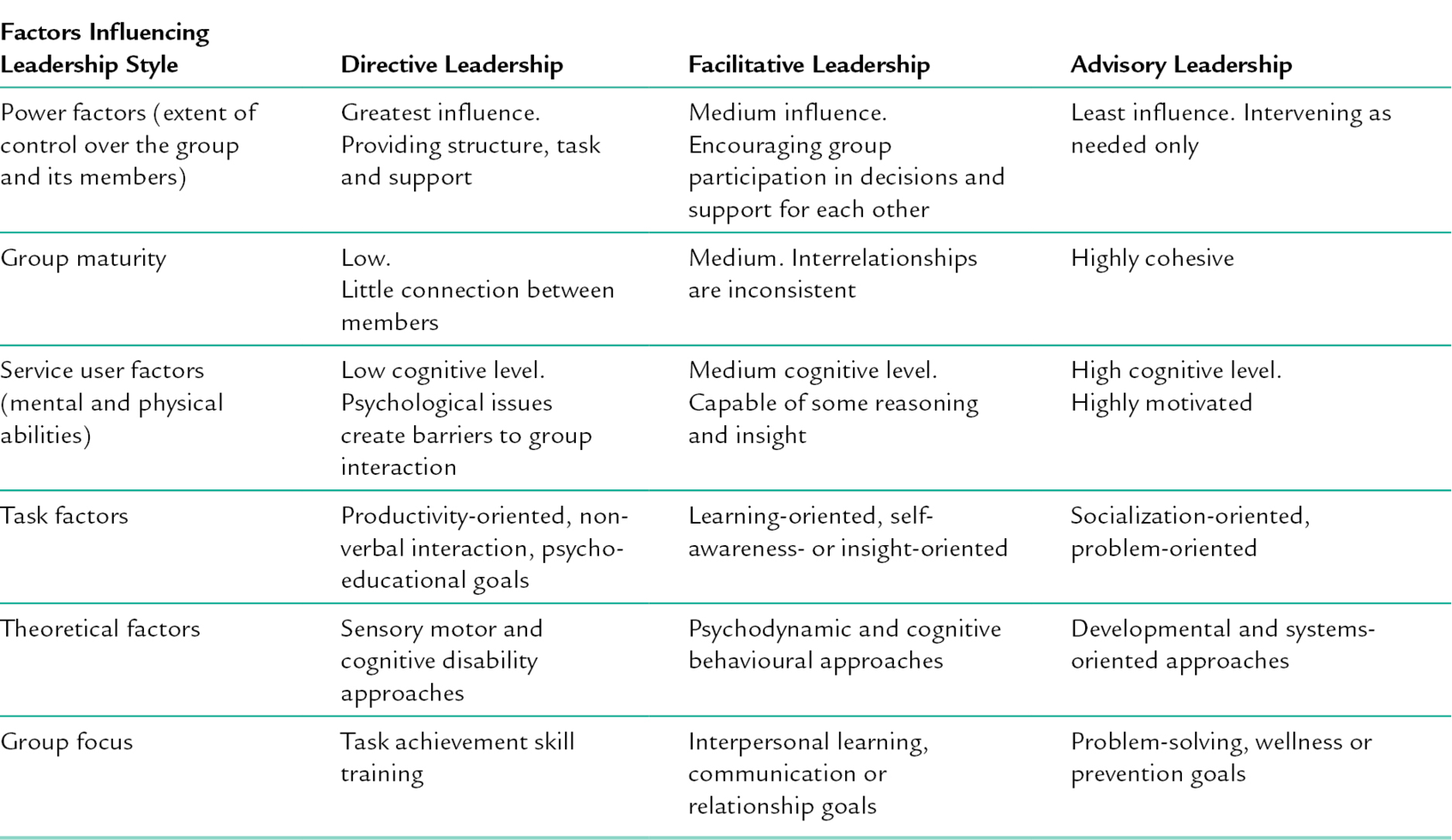

16 CHAPTER CONTENTS THEORIES SUPPORTING OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY GROUPS Professional Reasoning in Groups WHAT ARE CLIENT-CENTRED GROUPS? An Overview of Client-Centred Principles and Updates PRINCIPLES OF GROUP LEADERSHIP Three Styles of Occupational Therapy Group Leadership Poole’s Multiple Sequence Model Gersick’s Time and Transition Model Needs Assessment, Focus Groups Group Logistics: Size, Timing and Setting GROUP EFFECTIVENESS: THE EVIDENCE Occupational Therapy Group Evidence Occupational therapists have conducted groups since the profession began. In many mental health settings, groups may be the standard form of intervention, not only for practical reasons, but also to maximize the therapeutic power of member interactions for social learning and emotional support. This chapter provides an overview of group leadership, dynamics and the design of occupational therapy group interventions in mental health practice. Additionally, it reviews and gives examples of current evidence of group effectiveness. Several recent theoretical developments help to validate occupational therapy’s use of group interventions. First, the emergence of social identity theory affirms the importance of social learning in groups. Haslam et al. (2009) found ‘a wealth of evidence demonstrating the positive impact of social connectedness on health and wellbeing’ (p. 4). Additionally, complexity theory helps to explain the simultaneous levels of thinking therapists must master in order to design and lead effective groups, while client-centred principles shape the overall leadership approach of Cole’s Seven Step structure. Research on the impact of social identity (Haslam et al. 2009; Jettan et al. 2012) indicates that well-designed group interventions can have a powerful therapeutic effect on the physical and mental health of participants. Social identity is that part of self-identity that comes from one’s membership and roles in a variety of social groups (Sani 2012). For example, nurses, bankers and teachers are social identities associated with work groups, while mothers, sons, homemakers and breadwinners are social identities associated with family groups. These examples might also be considered ‘occupational roles’, because they imply specific sets of tasks. How well we perform these tasks in our own and others’ judgement has a significant impact on our self-worth. However, social identity is not limited to social roles. People may consider themselves members of a minority group (African American), a nationality (Mexican), a religious group (Jewish) or a stigmatized group (disabled). St Clair and Clucas (2012) found that self-categorization within marginalized groups still offers a buffer against environmental threats, giving individuals a sense of having the social support of their peers. For mental health service users, occupational therapy group leaders can build and support positive social identities of group members by incorporating client-centred principles such as inclusiveness, non-judgemental acceptance, respect and genuineness. Following the Seven Steps outlined in this chapter, will maximize the group’s potential for interaction, self-disclosure, mutual support and an appreciation of the therapeutic value of occupation, to enable continued participation in the social groups that make-up the lives of members. Group dynamics and occupational performance are complex phenomena. Put both together within a therapeutic group, and the number of interacting variables can be mind-boggling. Complexity theory bridges the gap between order (the scientific method, objective reality) and disorder (chaos theory, subjective realities). As applied to group dynamics, it acknowledges the existence of multiple factors influencing group behaviours and outcomes, some of which are, by definition, unpredictable. Yet, there are some theoretical principles that can be harnessed to increase the probability of positive outcomes; for example, Yalom’s therapeutic factors of universality, altruism and cohesiveness (Yalom and Leszcz 2005) or Bandura’s concept of self-efficacy (2004), reviewed later in this chapter. Florence Clark (2010), used the metaphor of ‘high definition occupational therapy: HD OT’ (p. 848), to illustrate the complexity of occupational therapy practice. In a high-definition picture, we can zoom in for a better look at the detail of a person’s face, the position of a tennis ball with respect to the foul line, or the number on a car licence plate, but then broaden the scope in order to take in the bigger picture, the multiple contexts within which the action takes place. Likewise, in complexity theory, scientific reductionism and complex holistic views can co-exist. For example, in applying theory, occupational therapists do not have to choose between a frame of reference, such as biomechanics (notably reductionist) and an occupation-based model, such as the Model of Human Occupation (Kielhofner 2008). Both views of the person are helpful in different ways, and one does not exclude the other. This theory helps to explain how an occupational therapy group leader considers each member individually, while simultaneously attending to the needs of the group as a whole. Acknowledging complexity paves the way to understanding the multiple levels of thinking that occur, often simultaneously, when facilitating an occupational therapy group. Schell and Schell (2008) describe the following types of reasoning that therapists employ: (1) scientific; (2) narrative; (3) pragmatic; (4) ethical; (5) interactive; (6) diagnostic; (7) procedural and (8) conditional. It may be thought of as the therapeutic equivalent of multi-tasking, shifting attention from one level to another as needed, to address the real-time situations of an interacting, ongoing group. While this may seem impossible, expert clinicians do this multilevel thinking automatically. For novice group leaders, much of this reasoning can be done at the planning stage. Cole’s Seven Steps (described later) remind group planners to incorporate multiple levels of generalization, beginning with a concrete shared experience, and moving through discussions of feelings, responses to one another, possible cognitive meanings of their actions and interactions and the potential applications of the lessons learned for each individual in his or her own life. When planning groups, it is first necessary to consider the typical challenges of a service user population and the published evidence about the effectiveness of certain interventions. Then, in matching the activity to the group members, they will analyse and grade the activity demands, and select an environment with appropriate characteristics. A frame of reference and/or occupation-based model of practice may guide the selection and adaptation of the group activity and environmental characteristics. These levels of thinking might be labelled diagnostic, procedural or scientific. However, when therapists begin to interact with members of the group, they may need to alter their original group design. Each member has their own history and life story (narrative reasoning) and set of life circumstances. The mission, values and practical limitations of the setting will also need to be taken into account (conditional). Service users are likely to express their issues and concerns from a particular point of view, and often they will wish for an immediate solution to particular problems. These immediate issues must be addressed in order to promote members’ interest in the activity and their engagement in the group process (pragmatic reasoning). The first thing a leader must do, is to establish a therapeutic group culture that includes respect, genuineness, open self-disclosure and non-judgemental acceptance (group values and ethics). Group leaders then engage in interactive reasoning and the therapeutic use of self in order to communicate empathy, encourage participation, facilitate interaction and otherwise assist members in developing trust in one another, and to move the group toward a state of cohesiveness; the ideal condition of all working groups. Most mental health occupational therapists understand the efficacy of well-facilitated groups. Students, however, need to first practice group leadership by facilitating groups of their peers, so that the steps become second nature and their own personal style can develop. Regardless of health challenges or disabilities, most people seek to recover lost roles or develop new or adapted roles in society. Facilitating engagement in occupations can support service users’ participation in desired social roles. When people understand the connection between occupational therapy group interventions and their own goals relative to social participation, their motivation to engage in group activities will usually increase (Cole and Donohue 2011). This connection is central to the client-centred focus of groups in occupational therapy. Client-centred groups follow the principles of client-centred practice originally defined by Carl Rogers (1961), such as non-judgemental acceptance (empathy for people with diverse viewpoints), conveying genuineness and respect (recognizing individuals’ inherent expertise and ability to problem-solve) and client directedness (enabling service users to choose the direction of therapy). Sumsion and Law (2006) updated the evidence for central concepts of client-centred practice, such as power sharing, communication, choice and hope, as evolving principles of client-centred practice. Creek (2003, p. 50) defined client-centred practice as ‘a partnership between therapist and client in which the client … actively participates in negotiating goals for intervention and making decisions [while] the therapist adapts the intervention to meet client needs’. When group members collaborate with the occupational therapy leader in setting goals and priorities, the client-centred therapeutic partnership is extended to the group as a whole. Based on occupational therapy’s appreciation of the environment as a context for performance, therapeutic groups provide a supportive social and cultural context within which people can experiment with new behaviours and learn to interact more effectively with others. For the new practitioner, Cole’s Seven Steps establish the basics of therapeutic group facilitation and this prototype can then be adapted as the therapist integrates further knowledge of various health problems, models of practice and frames of reference, levels of human development (age groups) and health or social care delivery settings. These seven steps address the full range of needs, including those of highly functional group members, and, as such, are appropriate for students to practice with their peers also. The session begins with stating one’s name, the name of the group and one’s role as the group leader. To assist the group members in learning one another’s names, in addition to stating names around the circle, members can tell the group something else about themselves that is unique, such as where they are from, what most concerns them about the group, even something as simple as their favourite colour. What is shared should match service user factors such as cognitive level, disability and age. Names should be repeated at the beginning of each session, not only as an introduction but as a way to acknowledge the importance of each member’s presence, a gesture which builds self-identity and encourages participation. For many groups, a warm-up activity – of 5 minutes or less – is highly recommended. It can capture group members’ attention (diverting them from whatever they came to the group thinking about) and prepare them for the activity to come. For example, members may choose picture cards with different facial expressions to express their mood as a warm-up for a group role play to promote self-expression. A warm-up can energize or calm. For example, a series of stretches may wake up an early morning group, while a short relaxation exercise might counteract agitation. Warm-ups may be formal or informal. When members know each other well, an informal chat about ‘how they are feeling today’, may suffice. Setting the mood is another function of the introduction. The group leader conveys this through facial expression, body language and tone of voice, as well as with words. The mood of the group should match the goals and content. If the activity of the day is light-hearted, the introduction can be upbeat (with humour, smiles and a playful exercise perhaps), while a more serious tone may be needed for topics, such as work readiness or coping with loss. Explaining the purpose clearly is vital to any introduction. It should occur after the initial greetings and warm-up, when members are alert and ready to listen. The goals and methods, and how the selected activity addresses the goals of members, should be clarified using everyday language. When people understand why they are being asked to take part in a group activity, they will actively participate more readily. In groups which focus on learning, sometimes introductory educational concepts are outlined. For example, a cultural awareness group may begin with a definition of culture and some exploration of group members’ perceptions of different aspects of culture. When member discussion is included, this may replace the warm-up, since it serves a similar purpose. The final component of the introduction is a brief outline of the session. For example, saying ‘we will be drawing for 15 minutes, then for the next 30 minutes we will share our drawings and discuss their meaning with the group’. This serves several purposes. First, the time limit gives group members a guideline for how detailed and complex their drawings should be. Second, it tells them that what they draw will be discussed openly with the group so they can decide to limit the content of their drawings to things they are willing to share. Third, it highlights that the emphasis of the group will be on discussion, not drawing, so they need not worry about their artistic ability. The point of the drawing is to clarify some aspect of the self and to communicate its meaning through discussion. Research has shown that the initial guidelines, including purpose and structure set forth in the first meeting, have a lasting influence on subsequent sessions (Gersick 2003). The activity provides the means or method for accomplishing group goals. In our prototype, this portion of the group lasts from 10 to 20 minutes and must generate enough raw material to sustain a meaningful discussion for the next 30–40 minutes. Activity selection is a complex process, based on the therapist’s knowledge of theory and research, activity demands, service user factors and health conditions. A simplified method of selection will be outlined here, with the expectation that the novice group leader will refine it, as knowledge and experience increase. This selection process includes activity analysis and synthesis, consideration of timing, goals, the physical and mental capacities of members and the skill of the leader. Most activities will need to be adapted for use with groups. This is accomplished through activity analysis and synthesis. Activity analysis is ‘a process of dissecting an activity into its component parts and task sequence in order to identify its inherent properties and the skills required for its performance, thus allowing the therapist to evaluate its therapeutic potential’ (Creek 2003, p. 49). Activity synthesis is ‘combining activity components and features of the environment to produce a new activity that will enable performance to be assessed or achieve a desired therapeutic outcome’ (Creek 2003, p. 50). The outcome of this complex matching process between member abilities, skills and preferences and the components of an activity determines the group activity selection. The timing of groups informs the choice of activity. Most group sessions last from 30–90 minutes, with an average of about an hour. If discussion is emphasized, the activity itself should take no more than one-third of the total session time. In addition, members of the group need to be able to work on the activity simultaneously within the same environment. Therapeutic goals will guide the selection of activities. In client-centred practice, service users’ goals are prioritized, and group leaders aim to form groups of people who have similar goals and priorities. Ideally, therapists should hold a group discussion of goals and priorities, as well as activity preferences before finalizing the group design. However, not all participants are capable of this level of collaboration. In such cases, the occupational therapy leader relies on pre-group interviews with individual members, carers and/or significant others, to identify potential group member goals and priorities. The physical and mental capacities of members will be a primary consideration in selecting any activity and formal or informal assessment of service users’ occupational performance should inform group member selection. Interventions work best with groups of people having similar functional abilities. For example, Claudia Allen (Allen 1999, Allen et al. 1992) defined six cognitive levels and 52 modes of performance, giving occupational therapy one of its most well-researched and detailed set of assessments of cognitive ability. Each level (especially 2–5) defines guidelines for task selection, analysis and adaptation, cueing (assisting) during task performance, and adapting the environment to enable people’s best ability to function. Allen suggested grouping people of similar Allen Cognitive Level. The group leader also considers their own experience and selects group activities based on familiarity, comfort level and past effectiveness. The activity should have a definite end. At that point, materials used during the activity are removed from view and the product is shared. The group leader may model sharing with their own example (such as drawing or writing) or may ask for a volunteer to start. The best way to make sure everyone gets a turn is to proceed around the circle, a norm which becomes automatic after the first few sessions. For activities which include group discussion as a common component, the sharing step is unnecessary. This addresses the questions: ‘How did you feel about the activity, the leader, and each other?’ Feelings are discussed first in order to prevent them from interfering with subsequent discussion. The group leader generates the discussion by asking open-ended questions, which require some elaboration. For example, asking ‘What was hard about communicating non-verbally?’ enables member expression of feelings of frustration, inadequacy or objection to the activity requirements. ‘Whose drawing most relates to you?’ encourages group interaction and emotional feedback responses. This addresses the question: ‘What did you learn?’ Abstract reasoning is needed to derive a few general principles from the data of the group activity. Again, group leaders facilitate generalizing by asking open-ended questions, such as ‘What were some common triggers of stress we shared?’ or ‘Which coping strategies are good or bad?’ Ideally, the general principles discovered by the group will closely align with group goals. For learning to be effective, service users need to understand how the principles learned apply to their own lives. The group leader asks questions that facilitate this connection such as, ‘What part of today’s activity will you take home with you?’ or ‘How can you use social skills in your life outside of the group?’ Each group member interprets the group experience in their own way. The application step offers each person the opportunity to verbalize the meaning of the group experience with respect to individual goals. Therefore, group leaders must ensure every member contributes to the discussion about applications and, if possible, gives a specific example. Assigning homework or keeping journals can reinforce the application of learning outside the group. A summary of the session reviews the highlights from each of the seven steps and reinforces the main principles learned. Preferably members should help summarize. Group leaders end by thanking members for participating and by sharing their own positive feedback on the group experience. Plans for the next session and reminders for application can be added as a final note. Group leadership is generally regarded as a formal position that carries with it certain responsibilities – such as selecting members, setting goals, designing the group methods and structure, and providing guidance during the sessions. Leadership has been defined as ‘the process of influencing group activities toward goal achievement’ (Shaw 1981, p. 317). A half century of research has concluded that there is no single preferred style of small group leadership. The consensus is that optimal leadership changes to meet varying needs and circumstances (Hersey and Blanchard 1969; Mosey 1986; Barge and Keyton 1994; Gouran 2003). Mosey (1986) suggested a multilevel approach to the leadership of occupational therapy groups. She defined five developmental levels for assisting people in learning group interaction skills (see Table 16-1). Mosey’s groups recapitulate (repeat) the normal sequence in which children learn to interact in groups. More recently, Donohue (2007, 2011, 2013) has validated Mosey’s developmental group theory using structured observation with children’s groups and mental health groups. TABLE 16-1 Mosey’s Developmental Group Leadership Occupational therapy group leadership may best be understood as existing on a continuum that encompasses directive, facilitative and advisory styles. One is not better than the others, but rather each is preferred in different situations. Choice of style is informed by factors such as participants’ abilities and maturity, goals of the task and theoretical approach (see Table 16-2).

Client-Centred Groups

INTRODUCTION

THEORIES SUPPORTING OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY GROUPS

The ‘Social Cure’

The Complex Nature of Groups

Professional Reasoning in Groups

WHAT ARE CLIENT-CENTRED GROUPS?

An Overview of Client-Centred Principles and Updates

COLE’S SEVEN STEPS

Step 1: Introduction

Step 2: Activity

Step 3: Sharing

Step 4: Processing

Step 5: Generalizing

Step 6: Application

Step 7: Summary

PRINCIPLES OF GROUP LEADERSHIP

Group Level

Occupational Therapy Leader Role

Activity Examples

Parallel

(directive leadership)

Providing task, structure and emotional/social support for members

Imitative group exercises, painting or other creative tasks, simple crafts

Project/Associative

(modified directive leadership)

Providing some choices of task, encouraging member interaction around task issues and awareness of others. The leader continues to provide support

Structured learning groups, Allen’s Level 3–4 craft groups

Egocentric – Cooperative

(facilitative leadership)

Members choose the task. The therapist facilitates interaction and assists members in meeting social and emotional needs

Task-oriented groups, insight-oriented verbal groups, self-exploration and communication-focused groups

Cooperative

(advisory leadership)

Relationships and socialization take precedence over task accomplishment

Members provide social/emotional support for each other

The therapist acts as advisor, provides resources as needed and assists with problem-solving or conflict resolution

Playing beach volleyball, having a birthday party

Group outings

Mature

(participatory leadership)

Members lead. The therapist participates as an equal co-member, using modelling, therapeutic self-disclosure and social learning to influence outcomes

Fund-raising events

Self-help groups

Three Styles of Occupational Therapy Group Leadership

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree