CHAPTER 108 Clinical Features

Neurology of Brain Tumor and Paraneoplastic Disorders

This chapter focuses on three subjects: the pathogenesis of signs and symptoms of brain tumors, the clinical presentation of patients with brain tumors, and the spectrum of central nervous system diseases usually included under the rubric of paraneoplastic neurological disorders. This review is necessarily brief. For a more in-depth treatment of the clinical presentation of brain tumors, see Shapiro and colleagues’ article.1 For the paraneoplastic disorders, see the paper by Darnell and Posner.2

Pathophysiology of Signs and Symptoms Associated with Brain Tumors

Generalized symptoms from brain tumors are manifestations of increased intracranial pressure, a result of the expanding tumor volume and the associated edema. Tumors may obstruct the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pathways, producing hydrocephalus. As the mass enlarges, intracranial pressure rises; brain tissue may be displaced through the rigid intracranial dural passageways, producing various herniation syndromes. Cerebral dysfunction and headache ensues. Abrupt headache and worsening neurological signs may accompany sudden increases in intracranial pressure that last 5 to 20 minutes. These episodes of raised pressure have a characteristic appearance on recording of intracranial pressure leading to their name, plateau waves.3

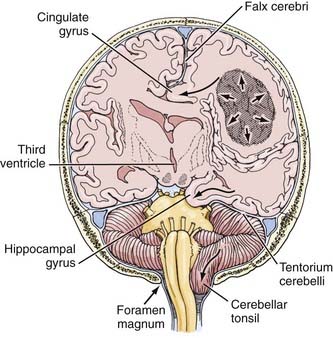

The herniation syndromes are life-threatening. Because the skull is divided into compartments by the relatively inelastic dura, an expanding mass in one compartment forces brain tissue through the openings between compartments, tearing blood vessels and compressing the neuropil (Fig. 108-1).4 A unilateral cerebral mass may force the medial surface of the brain beneath the falx cerebri (cingulate herniation). Transtentorial and tonsillar herniation may occur because of displacement of brain tissue through, respectively, the tentorial notch and foramen magnum. Table 108-1 lists the pathogenesis and clinical manifestations of the herniation syndromes.4

TABLE 108-1 Herniation Syndromes

| PATHOGENESIS | CLINICAL MANIFESTATION |

|---|---|

| CENTRAL HERNIATION | |

| Lateral and Forward Shift of Diencephalon and Upper Midbrain | |

| Diencephalic compression | Decreased state of consciousness, small pupils, Cheyne-Stokes respiration |

| Midbrain pontine compression | |

| Lower pons-medullary compression | |

| Tonsillar (Foramen Magnum) Herniation | |

| Posterior fossa mass pushes cerebellar tonsils through foramen magnum, compressing medulla | Rapid loss of consciousness, stiff neck, vomiting, skew deviation of eyes, irregular respirations, death |

| UNCAL HERNIATION | |

| Temporal Lobe Herniation through Tentorial Notch, Compressing | |

| Ipsilateral third nerve | Third nerve palsy |

| Posterior cerebral artery | Homonymous hemianopia |

| Midbrain | |

| Opposite cerebral peduncle | Ipsilateral hemiparesis |

Adapted from Posner JB, Saper CB, Schiff N, Plum F. Plum and Posner’s Diagnosis of Stupor and Coma, 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Cerebral edema accompanies growing brain tumors. It is produced mostly within a parenchymal brain tumor but also comes from the surrounding brain tissue as a result of the release of vasogenic permeability factors produced by the tumor, which act on brain capillaries.5 (The vascular permeability factor has been identified as vascular endothelial growth factor, which plays an important role in angiogenesis of tumors.6) Cerebral edema increases the total size of the mass. It is not unusual for a tumor of perhaps 20 g to produce a mass of nearly 100 mL because of the associated edema. Cerebral edema may also be produced by an extra-axial tumor, in which case the edema, also vasogenic in origin, comes only from the brain tissue itself.

Clinical Manifestations of Intracranial Tumors

General Manifestations

Mental Changes

Mental changes are a frequent general clinical manifestation of intracranial tumor (Table 108-2). They are often subtle in presentation and onset and may not attract the attention of friends and family members until the patient’s behavior becomes abnormal. Psychomotor retardation is the most common mental change accompanying a brain tumor. Characteristically, impersistence in routine tasks, emotional lability, inertia, faulty insight and forgetfulness, reduction in the range of mental activity, indifference to social practices, reduced initiative and spontaneity, and blunted affect are seen. Patients may sleep for longer periods, complaining that they seem unable to get through a day without taking a nap. Frank confusional states and dementia usually occur later and are more likely to accompany focal signs of brain disease. Alternatively, the change in the state of consciousness may progress to stupor and frank coma. Changes in personality may be described in “psychological terms”: depression, euphoria, impulsive behavior.7 In my series, almost 20% of patients have, at one time or another, sought psychological help for symptoms that, in retrospect, were clearly related to the tumor. Mental changes must be viewed together with other signs and symptoms, and especially with a history of progression of symptoms, to lead the physician to suspect a neoplastic process.

TABLE 108-2 Mental Changes Accompanying Brain Tumors

| PSYCSHOMOTOR RETARDATION |

| SLEEP DISTURBANCES |

| LANGUAGE DISORDERS |

| SOCIAL DISTURBANCES |

| “PSYCHOLOGICAL” SYMPTOMS |

Headache

Headache occurs in about 50% of patients with brain tumor at some time during the course of the illness.8 Headache is more prominent and tends to occur earlier when the tumor produces increased intracranial pressure. Of special importance is a headache that has recently changed in character, for example, becoming more intense, frequent, or longer lasting. Although classic brain tumor–associated headaches are severe, often worse in the morning, all brain tumor patients do not have morning headaches, and in fact may have head pain at any time of day or night.8 The head pain from brain tumor is often intermittent and may be described as deep, aching, or pressure-like rather than the more characteristic throbbing pain of migraine. It is often aggravated by the Valsalva maneuver, as in coughing or straining, and frequently becomes worse through change of posture. The headache that occurs in the early morning hours appears to be related to the recumbent posture and is thought to be associated with increased intracranial pressure as a result of lying down.

Generalized Convulsions

Seizures occurring for the first time in adults are more likely to be due to focal cerebral disease, especially neoplasms, than are seizures that begin in childhood, which are more often part of the epilepsies that are characteristic of this age group.9 Intracranial tumors produce both generalized major motor convulsions and various forms of focal seizures. Petit mal epilepsy is probably never due to a neoplasm, but minor temporal lobe seizures (partial simple or complex) that resemble petit mal attacks may accompany temporal lobe tumors. Jacksonian seizures that progress from one body part to another usually imply a lesion of the motor or sensory cortex. Lesions of the temporal lobe characteristically give rise to partial complex (psychomotor) seizures that may be associated with olfactory hallucinations (uncinate fits), disorders of visual or auditory perception, episodes of déjà vu, or automatic behavior.

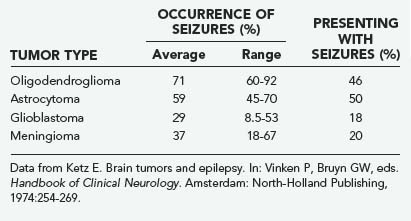

Seizures, both generalized and focal, occur in 25% to 50% of patients with cerebral tumors (Table 108-3).10 They are more likely to accompany slowly growing tumors than they are the more rapidly growing malignant neoplasms.11 A review of data of the Brain Tumor Cooperative Group (BTCG) database revealed that seizures occurred as the initial manifestation of tumor in 50% of patients with anaplastic astrocytoma but in only 27% of patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Seizures have been reported to occur in 25% of patients with reported malignant gliomas.12 Low-grade astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas are more likely to present as seizures than are other tumors; indeed, a single seizure is now the most common presentation of a patient with a low-grade glioma diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A syndrome of low-grade gliomas as a cause of chronic epilepsy has been recognized.13 Generalized seizures may occur with tumors in a variety of locations, whereas focal seizures are more common with tumors in the motor or sensory subcortical regions. Partial complex seizures are much more frequent with tumors of the temporal lobe than tumors located elsewhere in the brain. Seizures infrequently accompany infratentorial childhood brain tumors but occur in 22% of children younger than 14 years with supratentorial tumors and 68% of older teenagers with such tumors.14

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree