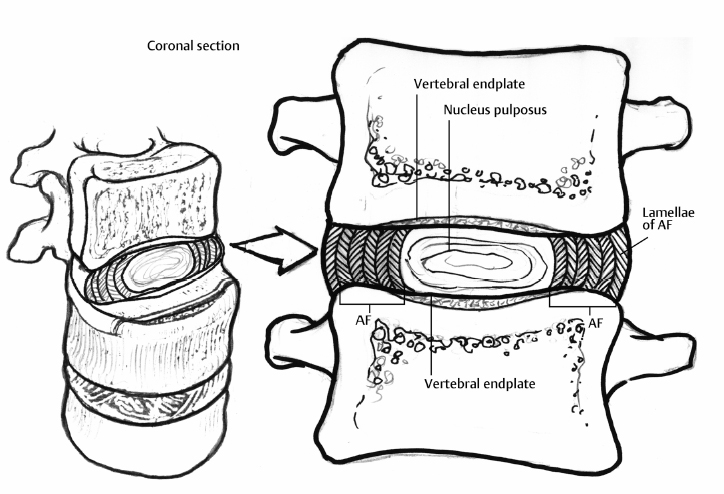

13 Clinical Presentation of Disc Degeneration Andrew P. White, Eric L. Grossman and Alan S. Hilibrand The intervertebral disc (IVD) is a vital and dynamic component of spinal architecture (Fig. 13.1). It assists in the distribution of loads and allows for stable yet complex motion. Over time, the disc undergoes a characteristic aging process that is manifested by consistent radiographic changes. In some patients, certain clinical signs and symptoms associated with disc degeneration may also be present. With advanced degeneration, the disc becomes less competent in appropriately distributing loads, and an alteration of normal spinal biomechanics may result. Increased strain on related structures, including the paired facet joints, can occur and can be associated with varied pathology. Regardless of the underlying physiologic process, the most common symptom seen with degenerative disc disease (DDD) is low back pain (LBP), which in a minority of patients may also be accompanied by neurologic symptoms.1 Fig. 13.1 Intervertebral disc cross-sectional anatomy. Note the oblique orientation of adjacent layers within the anulus. AF, anulus fibrosus. Repetitive mechanical loading may be related to the characteristic physiologic aging of the spine. Other factors may also be related, including the diminished porosity of the lamina cribrosa, resulting in decreased diffusion of nutrients and waste products. Over time, the IVD undergoes a characteristic degenerative process, with associated signs and symptoms often incident in the third decade. Early degeneration, including disc desiccation and loss of viscoelastic properties, leads to an alteration of spinal biomechanics. This can accelerate the degenerative process and ultimately cause pathologic conditions.1 With degeneration, the inner anulus fibrosus (AF) and the outer AF lose their nascent organization and differentiation; they take on a fibrocartilaginous character with indistinct boundaries. In particular, as degeneration occurs, the inner AF and the nucleus pulposus (NP) become virtually indistinguishable. As this occurs, the weakened lamellar structure of the outer AF becomes less resilient to applied forces and may develop defects that can predispose the disc both to herniations of inner disc material and to disc bulging.1 The NP in the younger IVD is composed of a high concentration of proteoglycan that helps maintain adequate water content and preserve viscoelastic properties. As aging occurs, maintenance of disc hydration becomes compromised secondary to the tenuous blood supply and decreasing nutritional diffusion. Furthermore, there typically is a decrease in overall proteoglycan content, which leads to an inability to maintain hydration. The IVD’s water content may decrease by ~20%. These changes ultimately alter disc structure, volume, and height. This change is associated with an alteration in spinal biomechanics.2 Immunohistochemical studies have demonstrated deeper penetration of the inner and outer AF by nerve endings in the diseased disc. Additionally, these nerve fibers have tested positive for substance P.3 Desiccation of the NP is seen with normal physiologic aging of the lumbar spine. This loss of water content and NP volume causes the “dark disc” phenomenon commonly seen on T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) sequences (Fig. 13.2). It is often associated with buckling of the AF. Subsequently, the balance between the breakdown and anabolic repair of trivalent pyridinoline cross-links, responsible for tissue cohesiveness, may be lost. This leads to apoptosis and degeneration of arterioles supplying both the disc and the vertebral endplates. Resultant loss of nutrient and oxygen supply causes excessive lactic acid production, more apoptosis, and additional degenerative changes.4 The most common clinical symptom thought to be directly associated with lumbar DDD is LBP. Neurologic symptoms such as radicular pain and neurogenic claudication may occur secondary to neural compression. Degeneration of intervertebral structures can be related to the development of neurological symptoms when loss of disc height, bulging of AF and ligamentum flavum, hypertrophy of facet joints, and other degenerative changes limit the space available for neural structures. LBP is the second most common reason that patients seek medical attention and is the fifth most common reason for all orthopaedic physician visits. It is common in industrialized countries, with prevalence estimates between 60 and 80%. The etiology of LBP is often related and or exacerbated by socioeconomic, psychological, biochemical, biomechanical, and other factors. LBP is a primary cause of physical disability and has an important socioeconomic impact. LBP may be caused by injury as well as the degenerative processes and may be affected by poor muscle conditioning or obesity. It may also be a presenting symptom of more serious conditions, such as tumor or infection. As such, evaluating physicians should consider “red flag” signs and symptoms that may motivate a more aggressive evaluation of patients with LBP (Table 13.1 ). Patients with LBP related to DDD typically present with nonspecific symptoms and without radiculopathy. Pain associated with DDD may arise from the paraspinal musculature, ligaments and tendons, facet joints, discs, and vertebrae. A distinct etiology is rarely identified, however. Degenerative anatomic changes in the spine that have been associated with painful disc degeneration include annular tears, herniated NP, and degenerative instability, including spondylolisthesis, lateral listhesis, and scoliosis. Patients with social and psychological stressors, depression, substance abuse, pending or past litigation or disability compensation, low socioeconomic status, work dissatisfaction, and a history of previous back pain are more likely to have persistent LBP.

Pathophysiology of Disc Degeneration

Clinical Presentation

Low Back Pain and Degenerative Disc Disease

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree