BIOMEDICAL INVESTIGATIONS

Investigations form a vital part of cognitive screening. All patients should have at least basic screening investigations in order to exclude potential reversible causes of dementia. At the very least, a full blood count, electrolytes, liver function and thyroid function tests, and urine specimen are indicated (see Table 15-1).

Anemia, hypothyroidism, and infections can cause cognitive changes, but with treatment, this may improve. Results of cardiovascular risk factors such as fasting glucose and lipids, and an HbA1C (Hemoglobin A1C) test will also provide further information, especially with regard to management. An ECG (electrocardiogram), if there is a history of cardiac problems, or chest X-ray, if there is a history of smoking, may also be recommended, but may not yield much further useful information. Other investigations such as calcium and C-reactive protein may be indicated.

Brain imaging is an important component of cognitive assessment and has been covered in detail in an earlier chapter. A structural brain image obtained with CT (computerized tomography) or MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) should exclude the presence of tumors, hemorrhage, significant stroke, or obstruction of CSF (cerebro-spinal fluid) flow. Focal atrophy may point to the likely presence of a specific cause for dementia (e.g., frontal atrophy in fronto–temporal dementias, hippocampal atrophy in AD), but generalized atrophy is less specific and is quite common in older people with intact cognitive function. Functional imaging such as SPECT (single photon emission computerized tomography) or PET (positron emission tomography) may be useful particularly where the diagnosis is unclear, if available as access will vary across the globe.

COGNITIVE SCREENING FOR DEMENTIA

It is important to emphasize that like a physical examination, the cognitive examination begins as soon as one lays eyes on the patient as opposed to a discrete section of the interaction with the patient. Clues about a patient’s cognitive function can be gleaned from the way they interact and converse during the interview and the accuracy, plausibility, and internal consistency of the content of their conversation. Simple demographic questions such as name, age, address, family structure, and current/past occupation can provide invaluable information. For example, a patient living in a nursing home may say that they are only visiting there, forget they are married or have grandchildren, or they may state their age as 35 years when in fact they are 75 years old. These questions also give an indirect indication of premorbid functioning through occupational information and a sense of their support structures. The history that is gathered from the patient and informants should provide fairly useful guiding information as your level of suspicion of the presence of cognitive impairment or dementia. It is also important to enquire about level of education, visual and hearing impairment, and language background in selecting and interpreting cognitive tests. The purpose of cognitive screening tools is to assist in the clarification of whether your suspicion is supported and therefore indicates the need for further investigation or specialist referral.

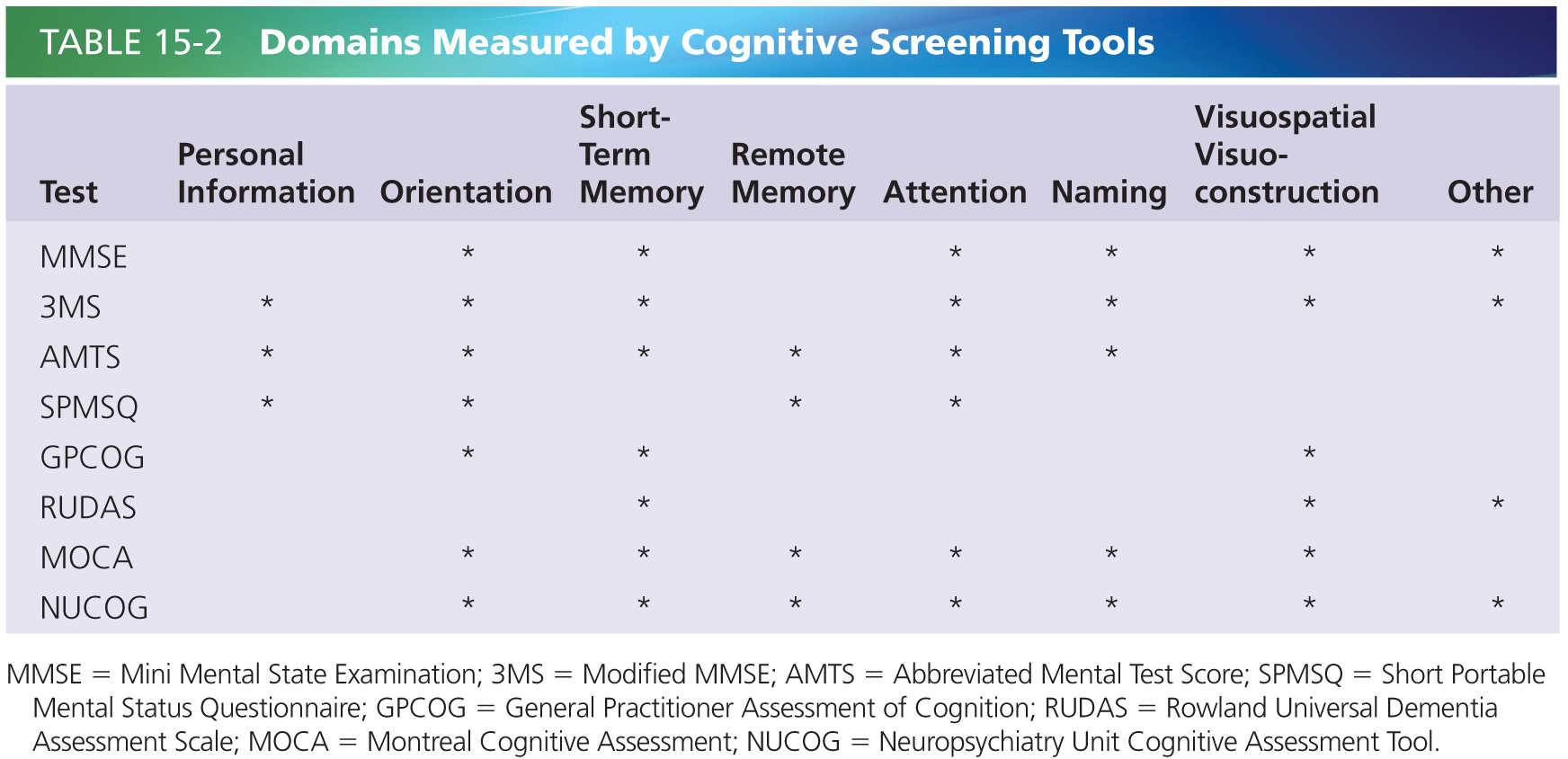

There is a plethora of tools available for use in cognitive screening. An ideal tool for screening is one that requires minimal training or equipment, is rapid to administer, is reliable, and has good sensitivity and specificity. Challenges in this area include accounting for different levels of education, different language backgrounds, different levels of baseline intellectual functioning, and sensory impairments. This chapter will focus on seven of the shorter clinician-administered tools that take up to 20 minutes or less to administer and one tool for informant history. They do not require extensive training to administer. Table 15-2 refers to the domains measured by the clinician administered tools adapted from Flicker 2010 [8].

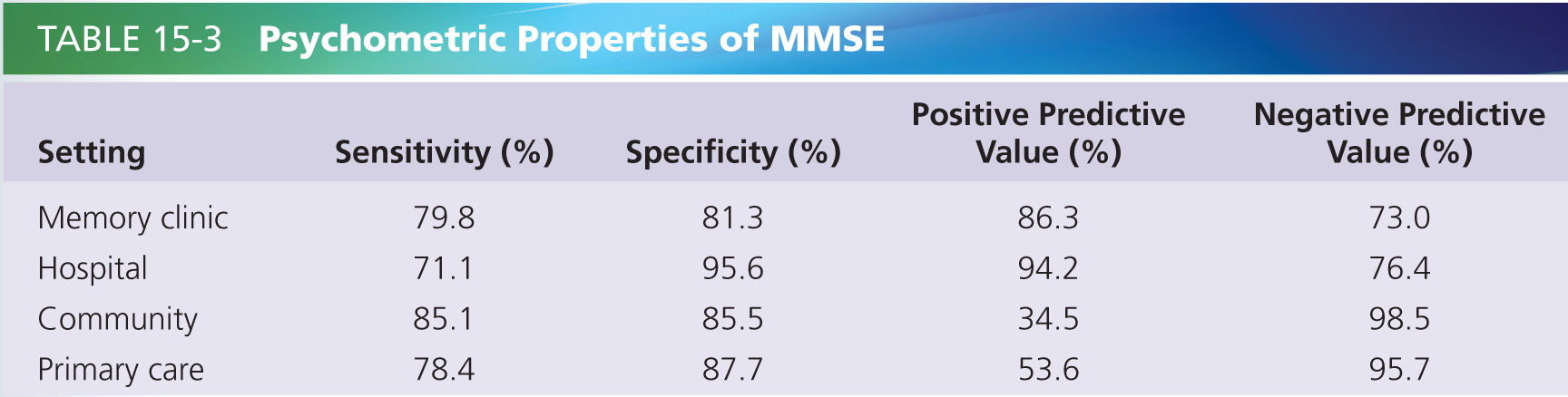

The most widely used screening tool is Folstein’s Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [9]. This is a 30-point tool that tests domains of orientation, short-term memory, attention, naming, and visuospatial function. A score below 24 is suggestive of dementia. This test has been shown to be reliable, internally consistent, and to have useful cutoff points, as shown in Table 15-3 [20, 26]. The psychometric properties show that it is useful at case finding (i.e., high positive predictive value) in clinical settings where there is high pretest probability and also is useful at ruling out dementia (high negative predictive value) in nonclinical settings [20]. A Cochrane review found that for the prediction of conversion from MCI to dementia, the accuracy of baseline MMSE scores had sensitivities of 23–76% and specificities from 40–94% [1]. It concluded that it is not predictive as a stand-alone tool but would still be useful in a screening process. One of its relative weaknesses is a lack of executive function testing. In clinical practice, this is often coupled with the clock-drawing test which assesses executive and visuospatial function [23].

Two modifications of the MMSE are also available: the Standardized Mini-Mental State Examination (SMMSE), which includes more detailed scoring instructions to improve objectivity, and the Modified MMSE Examination (3MS), which has modifications in the content and order of some existing items as well as the addition of four items with the aim of increased standardization of testing, sampling a wider range of cognitive function, and extending the floor and ceiling [5].

The Abbreviated Mental Test Score (AMTS) was described by Hodgkinson in 1972 [12]. It is a very quick-to-administer 10-point scale that tests domains of personal information, orientation, short-term and remote memory, attention, and naming. Again, a relative weakness is the lack of executive function testing, but this can be supplemented with the clock-drawing test. Its sensitivity for detecting dementia ranges from 73% to 100% and specificity from 71% to 100% [14].

The Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ) is a quick-to-administer 10-item tool which has demonstrated validity and reliability [5] and assesses personal information, orientation, remote memory, and attention.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree