CHAPTER 3

COGNITIVE THERAPY

Cognitive therapy, now often incorporated as a part of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), has emerged as one of the leading schools of psychotherapy over the past 40 years (A. T. Beck, 2005). Its achievements include a theory of psychopathology, a valid and useful way of conceptualizing the process of change, and specific techniques for reducing suffering. (In this chapter, the terms cognitive therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy are used interchangeably.)

Frank (1985) wrote, “A basic assumption of all psychotherapies is that humans react to their interpretation of events, which may not correspond to events as they are in reality” (p. 52). Cognitive therapy is an approach that has a central focus on the way individuals interpret events. States of emotional disturbance are seen as emerging from problematic, maladaptive, and/or unrealistic interpretations or information-processing systems. The core of cognitive therapy is the elucidation of these processes into consciousness that is then followed by a jointly enacted project to modify or eliminate these belief systems or schemas. As this therapy has developed, the full range of cognitive, interpersonal, behavioral, and Gestalt or emotion-focused techniques have been increasingly brought into play to facilitate this process. The successful adoption of these interventions has helped strengthen the belief that the cognitive-behavioral approach is the ultimate integrative therapy (Arnkoff & Glass, 1992).

HISTORY OF COGNITIVE THERAPY

In the following sections, we conceptualize the development of contemporary CBT by looking at the role of four streams of thought and effort:

Cognitive Therapies of Ellis and Beck

The first developmental step toward CBT resulted from the work of Albert Ellis and Aaron Beck. Ellis originally trained as a psychoanalyst but became concerned that many of his patients were not getting better. He came to realize that his patients’ thoughts and attitudes were rigid, problematic, and “irrational” and that these inflexible belief systems were contributing to the maintenance of their problems. As a result, he began to explore other means of understanding human thought and started working with his patients in a way that directly attacked these thinking patterns (Ellis, 2005). His efforts resulted in the publication of Reason and Emotion in Psychotherapy in 1962 and the birth of what would eventually be known as rational-emotive behavior therapy (REBT).

Among the different sources that Ellis drew on were Alfred Korzybski’s theory of general semantics, Alfred Adler’s individual psychology, and Karen Horney’s (1950) work on the “tyranny of the shoulds.” The Stoics have also been a major inspiration for REBT and cognitive therapy with their emphasis on the connection between interpretation and emotional pain or distress. As Epictetus wrote, “People are not disturbed by things, but by the view they take of them” (quoted in Ellis, 2005, p. 171). Marcus Aurelius affirmed, “If thou are pained by any external thing, it is not this thing that disturbs thee, but thine own judgment about it. And it is in thy power to wipe out this judgment now” (quoted in Bedrosian & Beck, 1980, p. 127). These ancient words are still at the core of contemporary cognitive therapy.

Early work by Ellis (Ellis & Harper, 1975) outlined commonly held beliefs that lead to emotional distress and discomfort. When patients reported experiences of distress, it was typically because they were maintaining one or more of these beliefs. Therapy became a kind of reeducation in which patients were actively pushed to change their outlook on life to one that was more in line with Ellis’s rational, humanistic philosophy. A core component of this philosophy includes an emphasis on long-term hedonism (what would bring the individual the greatest happiness over the long run).

Over time, Ellis changed his model from one that focused on the presence or absence of specific beliefs to one that focused on their structure. In his view, problematic life perspectives usually contain imperatives that take the form of shoulds or musts along with a general pattern of “demandingness.” The result is that REBT is centered on trying to redirect the individual’s way of thinking, and a common shift is to move from demands to preferences. In a typical REBT example, the goal might be to help a jealous patient shift from the negative belief of, “My wife must love me at all times, and if she does not it will be dreadful and catastrophic” to [the] affirming belief of, “Although I would like my wife to love me and stay with me for the rest of my life, I know that I would survive her leaving me and that there would continue to be ways for me to find pleasure and happiness in my life.” The essence here is not a denial of the seriousness of the situation, but rather a reinterpretation of it in a way that includes affirming the patient’s capabilities and the availability of other possibilities for pleasure and happiness. Despite its popularity, REBT appears to have failed to gain the mainstream acceptance that Beck’s approach has received in the cognitive arena (Prochaska & Norcross, 2007).

Aaron T. Beck, who many consider to be the father of cognitive therapy, also came to his approach from the psychoanalytic world. Paradoxically, it was his research on psychodynamic principles that ultimately led him to make the decision to forge a new way. He wanted to assess the content of depressed patients’ dreams to test Freud’s belief that depression was a manifestation of anger turned inward. To his surprise, he found that his patients’ dreams contained the same themes of low self-esteem that filled their talk during a session (Beck & Weishaar, 1989). These findings inspired Beck not only to begin an intensive study of the cognitions involved in depression but also to develop an effective therapy that built on these insights. This early work would lead to the publication of Cognitive Therapy of the Emotional Disorders in 1976 and Cognitive Therapy of Depression in 1979. The first book laid out the cognitive therapy model of psychopathology, whereas the second was one of the first detailed psychotherapy manuals published for the treatment of a psychiatric disorder (Weishaar, 1993). As Beck developed his model, he drew on the work of the Stoics, Alfred Adler, the ego psychologists, Karen Horney, and George Kelly (1955).

Beck also integrated techniques from behavior therapy. He appreciated the scientific foundations and focused investigations of the behaviorists, but he explained their success differently; he felt that their true curative power was that the experiences they provided led to changes in cognition (Bedrosian & Beck, 1980).

Beck was unaware of Ellis’s work when he first began developing his approach. Ellis contacted him after his first publication, and they have corresponded over the years (Weishaar, 1993). Although sharing an emphasis on the power of belief and interpretation in the development and maintenance of psychopathology, there are a number of differences between Beck and Ellis.

The first is that Ellis’s approach is fundamentally a philosophical one; a person’s suffering decreases as he or she develops a different life perspective. This philosophy led him to a more educative treatment approach in which teaching his humanistic philosophy was central. Beck, in turn, is connected to science (R. K. James & Gilliland, 2003), and he uses the metaphor of the personal scientist in his model (A. T. Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979; Mahoney, 1974). In a therapy setting, he would not directly challenge a problematic belief, as Ellis might; instead, he would explore the full ramifications of the thought and might work with the patient to develop experiments to gather evidence that would support or refute the validity and the usefulness of the belief.

A second way the two differ is that Ellis believes that a core principle of demandingness, in the form of shoulds and musts, underlies most or all psychopathology. Ellis emphasized universal principles rather than making a direct connection between specific thought profiles and specific disorders, as Beck did.

Cognition and Behavior Therapy

The second stream of activity that led to the development of CBT was the work of such theorists as Michael Mahoney (1974), Donald Meichenbaum (1992), and Marvin Goldfried (2003), among others. Behavior therapy, deriving from the work of John Watson and later B. F. Skinner, eschewed an emphasis or interest in “mentalistic” or internal phenomena. If psychology were to be a true science, there would need to be an emphasis on observable and measurable behavior; thoughts, images, and dreams were not felt to be appropriate for this kind of research (Wilson, 2005).

The classic behavioral tradition not only provided a strong scientific basis for psychology and psychotherapy but also led to therapeutic interventions that were effective in the treatment of a wide range of disorders (see Chapter 2). Nonetheless, by the early 1970s, problems in the paradigm were beginning to emerge (Mahoney, 2000). The result was a kind of revolt in the behavior therapy world because therapists and theorists began to embrace cognition in their work (Arnkoff & Glass, 1992).

The cognitive revolution meant that a crucial element in the effectiveness of behavior therapy was how it influenced the thinking of patients and how they interpreted stimuli, chose their responses, and evaluated the consequences of their actions. This led to a re-envisioning of behavioral strategies and the inclusion of Beck’s work as a form of cognitive restructuring (Wilson, 2005).

The behavioral tradition has also emphasized the importance of social skills and self-efficacy, both of which are useful additions to the cognitive component. Patients may be upset because their cognitions are skewed, but they may also be distressed because they actually lack social skills or assertiveness (Wilson, 2005). Bandura’s (1977) work on self-efficacy is relevant here as well. People may have varying levels of competence as they go from situation to situation; for example, a carpenter may feel very assured in his ability to build things, but he may find the task of addressing his coworkers in the morning meeting to be quite daunting. Successful training in assertiveness not only gives him new skills but also potentially changes his cognitions about himself and his work.

Constructivism

The constructivist revolution in the social sciences, which was connected to the larger postmodernist zeitgeist informing many academic disciplines, also played a role in the further development of CBT. Constructivism emphasized that much of social experience was created and that consent and authority played a major role in what was seen as acceptable, good, and true (Berger & Luckmann, 1967).

For psychotherapists and patients, constructivism offered a new kind of freedom—the freedom of self-definition (Neimeyer, 2002). The story of a person’s life could be told in different ways: “What would it look like if I organized my life by my successes? By my emotional experiences? By my dreams? By moments of profound spontaneity? By experiences of grief and loss? By acts of assertiveness or courage?” Each of these can be an organizing stimulus to help create a new narrative of the past while serving as a new structure for the future.

One of the great possibilities here is a sense of fluidity that the self and identity are not solely defined by family and society. Therapy, in this regard, becomes a process of co creating a life text, of empowering patients to be the authors of their lives (see Chapter 6).

Recent Developments

In addition to schema therapy, which is discussed later, other more recent psychotherapy developments include dialectical behavior therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, and the cognitive therapies that utilize mindfulness techniques. These are discussed in Chapter 5. McCullough’s Cognitive-Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy is also emerging as an effective treatment for patients suffering from chronic depression (McCullough, 2000, 2003).

THEORY OF PERSONALITY AND PSYCHOPATHOLOGY

Schemas

At the core of the cognitive perspective on personality and psychopathology is the schema (A. T. Beck, Freeman, & Associates, 1990; Young, 1990). Schemas are psychological information-processing and behavior-guiding structures that develop during childhood and adolescence. They serve as a map or blueprint of life and the world, and they provide the individual with both information and meaning. Individuals have numerous schemas about all aspects of life including relationships (i.e., how to deal with authority figures) and interactions with objects (i.e., how to drive a car). According to Beck, there are five kinds of schemas: (1) cognitive, (2) affective, (3) motivational, (4) instrumental, and (5) control. The cognitive schemas are involved in such processes as abstraction, interpretation, and recall; the affective schemas are connected to emotions and feelings; the motivational schemas are involved with wishes and desires; the instrumental schemas organize the system for action; and the control schemas are a regulatory force—they monitor behavior and work to inhibit or redirect it (Beck et al., 1990, p. 33). In psychopathology, there is a particular interest in schemas related to the self, others, the world, and the future.

Beck (A. T. Beck et al., 1990) has outlined some of the characteristics of schemas: Breadth refers to the amount of psychological or interpersonal terrain a given schema covers. Some may apply to relatively discrete situations, whereas others may pertain to a wide range of encounters. Of special relevance to psychotherapy is the degree of flexibility or rigidity of a schema. Piaget (1983) looked at this issue in his work on assimilation and accommodation. As an individual goes through life, there is a constant flow of information and feedback about the nature of him or herself, his or her actions, and the world. Some of this information supports the schemas that are already in place and some conflict with it. With assimilation, the individual interprets these events in ways that maintain the integrity of the schema; with accommodation, the individual changes the schema to incorporate the new and conflicting information.

One crucial factor here is that, as maturation takes place, humans favor assimilation over accommodation. They will work to keep their existing schemas intact. This means that if a negative or dysfunctional schema begins to develop early in life, the child continues to interpret his or her experiences in a distorted way that may help to strengthen the schema (J. S. Beck, 1996). In more extreme life situations, distorted or maladaptive schemas may have been accurate and even adaptive within the context of a particularly problematic family environment; they are, however, no longer helpful once the individual engages with the outside world (Young, Beck, & Weinberger, 1993). Psychotherapy for schemas is fundamentally an endeavor that seeks to challenge, modify, and, in some cases, replace existing schemas and the corresponding disturbances in information processing. Given this, practitioners, in turn, will seek to favor accommodation over assimilation. In general, the more serious the pathology, the more rigid the schemas in place are.

Schemas may have different levels of prominence in the schema structure—some are only occasionally present, whereas others have the potential to play a role in most situations. The valence of a schema is its level of activation at any given time. During a state of latency, the schema is not influencing actions or interpretations, but once activated, it can be a contributing or even a ruling force. In the different psychiatric disorders, problematic, maladaptive, and inaccurate schemas are dominant, and it seems that they have the ability to supplant and inhibit more adaptive interpretation systems. It is the power of these schemas to preclude the more adaptive ones from regaining control that distinguishes the experience of “being moody” from having a disorder. With a mood, a problematic schema may be dominant for a brief period of time, but it is then supplanted by a more adaptive one. In the Axis I disorders, such as depression or a specific phobia, these schema shifts are often longer lasting, but ultimately temporary. In the case of depression, they may be time-limited, and in the case of a phobia, they may be situation-specific. In the Axis II or personality disorders, these problematic schemas can maintain their dominance for a lifetime (J. S. Beck, 1996).

Beck emphasized the role of distinct cognitive profiles at the core of each disorder. These interpretive systems were biased in specific ways. For example, depressed patients demonstrated a consistently negative view of themselves, the world, and the future. In anxiety disorders, patients were experiencing a sense of threat on symbolic and/or physical levels. In panic disorder, the mental and physiological symptoms of anxiety and stress were misinterpreted as indications of insanity or coronary arrest. With suicidal behavior, patients frequently expressed hopelessness about the future while demonstrating a great deal of difficulty generating life alternatives and productive problem solving (A. T. Beck & Weishaar, 2005).

With the personality disorders, there are also deeply problematic core themes at work. Dependent patients feel that they are helpless and seek ways to connect to others for protection and caregiving. Avoidant patients may be attuned to the possibility of being hurt in interpersonal relationships and so stay away. Obsessive-compulsive individuals have central concerns about mistakes and errors. They compensate by seeking perfection in many or all areas of their lives. The histrionic patient may feel that his or her interpersonal needs will only be met if he or she can impress others. The result may be a dramatic and attention-seeking style (A. T. Beck et al., 1990). In all of these disorders, the dysfunctional schemas lead to problematic reactions to events because there is a systematic bias in the way that they are interpreted.

As a result of the vicissitudes of individual experience, some patients may develop schema structures that lead them to be more susceptible to certain stressors. These are known as cognitive vulnerabilities (A. T. Beck & Weishaar, 2005). Some people may be more prone to develop depression when faced with obstacles in the area of achievement, whereas others may develop it in relation to interpersonal difficulties and loss (A. T. Beck & Weishaar, 2005; Blatt, 1995).

Cognitive Distortions

In times of stress as well as in states of psychopathology, the cognitions become distorted both in content and structure. Although these are overlapping processes, it is possible to distinguish the two. One of the functions of these distortions is to bias the interpretation of information and events in such a way that the underlying schemas remain unchallenged (A. T. Beck, 1987; Bedrosian & Beck, 1980). These processes appear to favor polarized thinking and/or the selective processing of some data to the exclusion of others.

Beck has outlined a number of processes that are frequently used by patients, including:

- Arbitrary inference: Coming to a conclusion that is either not supported by existing evidence or is actually in defiance of it.

- Selective abstraction: Conceptualizing a situation based on a detail; however, the bigger picture is not taken into consideration so that the conclusion is out of context.

- Overgeneralization: Creating a rule that is based on a few specific (even one) instances, which is then applied to many other situations, even those for which it is not appropriate. Patients may also make global judgments about themselves based on a few (or even one) incidents.

- Magnification or minimization: Seeing things as either more or less important than they really are. This distortion is so extreme that it is detrimental to the individual.

- Personalization: Attributing the cause of outside events to yourself even when there is no evidence that this is the case. The psychotic symptom of ideas of reference is an extreme example of this (Bedrosian & Beck, 1980).

- Dichotomous (or polarized) thinking: Interpreting things in terms of extremes. Events are classified as either totally good or totally bad; there is no middle ground.

- Incorrect assessments regarding danger versus safety: Sensing risk as disproportionately high. This distortion is commonly found in anxiety disorder patients, and the result is that they live lives of fear and restriction. The opposite version of this is found among those who have repeated accidents or who keep getting themselves in trouble because their sense of risk may be too low (A. T. Beck et al., 1979; A. T. Beck & Weishaar, 2005; Bedrosian & Beck, 1980).

For example, a college professor gave a lecture and noticed that, although most people seemed attentive, one student fell asleep. The man thought about this individual and became distressed as he focused on the idea that he had given a terrible class—as evidenced by the sleeping audience member. This is an example of selective abstraction, of misinterpreting events in a way that fits the problematic schema while ignoring data that contradict it. In this case, the professor was prone to themes of failure and rejection, so the sleeping student was particularly meaningful to him (Bedrosian & Beck, 1980).

Definitions of Health

Although cognitive therapists do not appear to write directly about psychological health, it is probably fair to say that mental and emotional well-being would build on an accurate view of oneself and the world, adaptive core beliefs, and healthy behavior patterns. In any event, the degree to which individuals are unable to move toward their goals freely, are filled with inner pain and anguish, and are having repeated experiences of conflict with others may be a clinical measure of their psychiatric health or disturbance.

Sources of Pathology

Such factors as genetics, disease processes leading to brain function damage, inadequate parenting, and difficult familial and social situations can all contribute to problematic outcomes (A. T. Beck & Weishaar, 1989). Whether psychopathology occurs and the form that it takes involves interplay among these forces and the creative energies of the individual (Hall & Lindzey, 1978). For the psychotherapist, the endpoint of this process is manifested in the schemas.

Emotional distress often takes place in response to real or perceived threats to the patient’s personal domain, which includes the things that are held to be important. This domain not only includes material goods but also symbolic possessions such as a sense of self, physical appearance, qualities of character, values, goals, family, and friends. Other emotionally laden aspects of the domain include identifications with ethnic groups or institutions that a person has been a member of. Last, values such as freedom or equality can maintain this status as well (Bedrosian & Beck, 1980).

THEORY OF PSYCHOTHERAPY

Goals of Psychotherapy

Patients frequently enter therapy with a desire to eliminate the pain that they are experiencing, with a hope that they can achieve desires that have been eluding them (e.g., finding a job) and/or in response to criticism and pressure from important people in their lives. These are not discrete endeavors; instead, they often overlap and interact. However, although the symptoms or problems are the starting point, the work proceeds with the understanding that it is the patient’s belief system that is the primary source of difficulty and that the ultimate goal of therapy is to uncover and change it.

Assessment Procedures

Assessment is typically done in a multimodal framework. This may involve a clinical interview focusing on the current situation, the use of empirically validated tests and measures that look at both symptom levels and underlying constructs, and a review of patient history to help get a sense of predisposing and precipitating factors.

Beck has developed a series of assessments to measure levels of pathology and pathogenic beliefs. Perhaps the most famous of these is the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; A. T. Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961), and its more recent update, the BDI II (A. T. Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996), an instrument that is widely used in both clinical and research settings. Other commonly used instruments include the Beck Hopelessness Scale (A. T. Beck, Weissman, Lester, & Trexler, 1974) and the Beck Anxiety Inventory (A. T. Beck & Steer, 1990). Moving beyond formal assessment measures, the first phase of treatment is geared in part toward identifying the symptoms and problems, as well as the cognitions that maintain them, and an array of techniques are used to accomplish this.

Process of Therapy

Therapist Role

As noted earlier, cognitive therapy is a collaborative endeavor in which both participants work together to solve the patient’s problem. Beck (Young et al., 1993) has noted that successful cognitive therapists usually have a discrete set of qualities. The first of these are the nonspecific ones that are shared by many therapists such as “warmth, genuineness, sincerity, and openness” (p. 242). In many respects, these overlap with the ideal characteristics proposed by Carl Rogers (1986).

Beyond this, therapists should be able to understand correctly, through the use of empathic listening, how patients experience their world. Therapists should be adept at logical thinking and at strategic planning and be willing and able to take an active stance, leading and structuring the work.

This also means that the therapist should adopt the role of an investigator, not an authority (Bedrosian & Beck, 1980). The great temptation in cognitive therapy is to tell patients how they should be thinking rather than working with them in a manner that allows them to transform their perceptions (A. T. Beck & Weishaar, 2005).

Therapeutic Alliance

The therapeutic relationship or alliance is the foundation for success in all psychotherapy (Teyber & McClure, 2000; Waddington, 2002), and cognitive therapists place a strong emphasis on maintaining a good relationship with their patients. Self-disclosure is allowed if it serves the goals of the therapy, and this includes revealing information that helps build the alliance and/or provides evidence in opposition to the beliefs contained in the dysfunctional schemas.

The use of feedback helps to keep the channels of communication clear and open. By clarifying the patients’ understanding of and their feelings about in-session activities and homework, possible problems or misunderstandings can be caught early. In addition, disruptions and misunderstandings in the alliance give both parties an additional opportunity to understand and change the automatic thoughts and schemas that are involved (Waddington, 2002).

Collaborative Empiricism

Collaborative empiricism is the centerpiece of the therapist-patient connection, and it is the process by which the patient and the therapist form an investigative team (Young et al., 1993) that identifies the problems and goals, determines the priorities, and sets the specific agenda for each session.

Working with automatic thoughts, assumptions, and schemas are the essence of the therapy. Continuing with the scientist metaphor, collaborative empiricism means that each of these cognitions can be approached as if it were a hypothesis to be tested, and that the patient and therapist can work together to decide how to do this.

Length and Phases of Treatment

In the traditional treatment of Axis I disorders, cognitive therapy usually consists of 12 to 16 weeks of once- or twice-per-week sessions with some follow-up or booster sessions in later months (A. T. Beck & Weishaar, 2005). The treatment of Axis II or personality disorders can take a much longer period of time (Young et al., 2003).

Cognitive therapy can be seen as occurring over two phases. In the first phase of treatment, there is an emphasis on building a relationship with the patient, socializing him or her into the cognitive model, targeting symptoms and problems, organizing the priorities, and taking steps to identify the automatic thoughts or the first level of cognitions supporting the disturbance (Young et al., 1993). In short, the patient and therapist work to formulate a cognitive understanding of the problem and then develop a treatment plan to address the specific symptoms or difficulties (A. T. Beck, 1987). With some depressed patients, it may be important and necessary to start with behavioral interventions to increase their activity level. This could include methods such as (a) activity scheduling to help them become more organized, (b) mastery and pleasure monitoring to challenge their beliefs that they cannot do anything and that nothing is enjoyable, and (c) graded task assignments to help them take small steps toward completing tasks rather than trying to do everything at once (Bedrosian & Beck, 1980). After they have made some progress in these spheres, patients may be more amenable to cognitive work.

The second phase of treatment includes efforts to clarify and change the underlying schemas. This kind of work is covered in the later discussion on schema therapy.

Socratic Dialogues and Guided Discovery

The use of questions is a central activity in cognitive therapy, and this approach is known as the Socratic dialogue. The intention of the questions is to:

- Clarify or define problems.

- Assist in the identification of thoughts, images, and assumptions.

- Examine the meanings of events for the patient.

- Assess the consequences of maintaining maladaptive thoughts and behaviors (A. T. Beck & Weishaar, 2005, p. 253).

In the beginning, the goal is to reach a state of clarification and enable the therapist to have an empathic understanding of the patient’s world; later, it is to create alternatives. Again, this involves delineating the negative consequences of the patients’ perspective (A. T. Beck & Weishaar, 2005).

Guided discovery is another way to understand and change these thoughts and assumptions. The first part is a historical review to see how the disorder and the underlying schemas developed and what the contributing and mitigating experiences were. As Beck put it, “the therapist and patient collaboratively weave a tapestry that tells the story of the patient’s disorder” (A. T. Beck & Weishaar, 2005, p. 240). The next step is for the therapist to work with the patient to create experiments, both inside and outside the consulting room, to test the validity of the schemas (A. T. Beck & Weishaar, 2005).

Automatic Thoughts and the Daily Thought Record

A central focus of exploration is automatic thoughts that provide an entryway into the problematic inner world of the patient. The automatic thoughts are the interpretive force that follow the external or internal stimulus and help determine emotional and behavioral consequences (A. T. Beck & Weishaar, 1989). These thoughts reside on the periphery of consciousness, and the patient may have to make some effort to access them (A. T. Beck, 1987). They are, however, not that difficult to identify, and a patient’s ability to do this can be improved with practice.

Automatic thoughts can be seen as occupying the top of a pillar in which the underlying assumptions (or “if-then” propositions) are in the middle and the schemas constitute the foundation. However, these are not always thoughts and may take the form of images (A. T. Beck, 1987).

As a vehicle of interpretation, patients’ automatic thoughts filter the incoming information and determine the emotional and behavioral response. In psychopathology, the filtering is biased and the patient’s automatic thoughts frequently utilize the cognitive distortions that were discussed earlier.

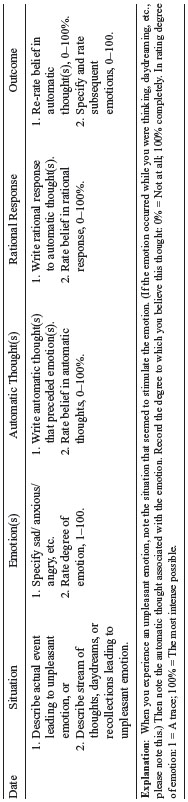

To change this situation, there must be a way to get a clear picture of them. One way to do this is through the use of the daily thought record (DTR). This instrument is a vehicle for enabling patients to get access to their cognitions during times of duress. As can be seen in Table 3.1, the form contains five columns. The first is the identification of the patient’s problematic event, either an external one (e.g., an interpersonal conflict) or an internal one (e.g., a disturbing memory, image, or thought). The second column identifies the emotion and rates, on a scale from 1 to 100, the corresponding level of distress; the third column is the place where the automatic thoughts are identified and the degree to which it is believed is also rated on a percentage scale from 0 to 100. Later, the patient uses the fourth column to write down a counter-interpretation that leads to lower levels of distress. In the last column, they then rate how much they actually now believe the original automatic thought.

Table 3.1 Daily Record of Dysfunctional Thoughts

Source: “Depression” (p. 250), by J. E. Young, A. T. Beck, and A. Weinberger, in Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders, second edition, D. H. Barlow (Ed.), 1993, New York: Guilford Press.

When starting to use this instrument, identifying any automatic thoughts is the primary goal. The patient can then undergo the kind of examination that is discussed later in the chapter.

The creation and effective use of rational responses is a process. As the DTR is used and the automatic thoughts are identified and elucidated, the patient and therapist can work together to formulate a more rational or adaptive response. An entire session can be devoted to this project. These responses can take the form of a script and role-playing can be done to help the patient rehearse them in an emotionally aroused manner. The homework for the week can include applying them in trigger situations. The ultimate goal is for the patient to be able to spontaneously create effective responses when problematic thinking and emotions arise (Bedrosian & Beck, 1980).

Strategies and Interventions

Leahy and Holland (2000) have provided an excellent guide to working with the various cognitive intervention techniques that has served as a primary source for this section. These techniques can be organized according to their target, be it automatic thoughts, underlying assumptions, or the core schemas.

Addressing Automatic Thoughts

Defining the Terms

This is particularly useful when patients describe themselves in negative ways. For example, they may be asked to define what they mean when they say they are a “failure” and, in turn, what they mean by “success.” Working with these two terms can be particularly enlightening as: (1) patients may be making global assumptions about themselves based on their behavior in a few instances; and (2) their standards of success may be disproportionately high.

Examining the Evidence

A core technique is working to marshal all of the evidence that both supports and refutes a belief. This can be laid out clearly and the relative weight of each argument can be assessed.

Testing the Thoughts

Just because an individual holds a belief strongly does not mean that it is true. Ideally, there should be a way to test the validity of the belief in the real world. Using a guided discovery process, the patient and therapist can work together to design an experiment to resolve the question.

Generating Alternatives

Taking a slightly different approach, patients can be asked to generate alternative explanations or hypotheses (“My boss cancelled our meeting because she is getting ready to fire me,” versus “My boss cancelled our meeting because something came up that she needed to attend to.”).

Maladaptive versus Inaccurate Beliefs

Examining beliefs may be helpful in situations in which patients are resistant to changing their belief in the “correctness” of their thoughts. Instead of focusing on the possibility that the thought is distorted, the emphasis can shift to whether the belief is helping them to achieve their goals (Schuyler, 2003). Some beliefs may be extremely costly in the energy and the effort needed to carry them out. Patients who believe that “everyone must like them” may find social situations to be enormously stressful because they must continuously monitor their own and other people’s behavior.

Cost-Benefit Analysis

A cost-benefit analysis often is combined with an examination of maladaptive beliefs. Here, patients assess what they gain and lose from maintaining a belief. Asking them to rate the relative impact of its costs and benefits can help them see the problematic side of their dysfunctional thoughts.

Positive Reframing

A further variant is to try to see if a positive meaning can be made out of a negative situation (e.g., “The embarrassing situation that I got into when I was drinking really showed me the danger that alcohol use poses in my life.”). The issue of meaning can also lead the therapy into areas of existential exploration (see Chapter 8, this book; Yalom, 1985).

Examining the Logic of Thoughts

Thoughts can be evaluated for their logic and completeness. Is the patient making a global self-judgment based on a specific incident (“Because I had a bad date the other night, I will be lonely for the rest of my life”)? Are they jumping to conclusions based on incomplete information?

Pie Technique

With patients who are concerned about their level of responsibility for events, a pie chart can be drawn up to assess all of the factors involved. In a situation in which a child is not doing well in school, a parent’s self-blaming behavior may not be appropriate. Other factors could be the presence of learning disabilities or attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, the quality of the teachers, the student’s motivation, the fit between the child and the school, the impact of youth culture, the possibility of depression or anxiety in the child, and so on. If it turns out that the quality of parenting has not been sufficient, the therapist and patient could do problem solving to find ways to improve this, perhaps by reading a book or taking a course.

This connects to the larger issue of looking at mitigating factors and the attribution of responsibility for success and failure. Depressed patients often attribute failure to themselves and success to external factors (i.e., luck or the kindness of others). For those who attribute high levels of responsibility to themselves, an exploration of potentially relevant factors such as “provocation, duress, lack of knowledge or preparation, lack of intention, failure on others’ parts, task difficulty, [and] lack of clear guidelines” could be helpful. (Leahy & Holland, 2000, p. 308).

Downward Arrow or Vertical Descent

The downward or vertical arrow technique is a way to move from automatic thoughts to deeper assumptions or schemas. In this technique, the patient is asked to imagine that their automatic thoughts were true; the question then arises as to what would be so terrible if this were the case. This process is then continued with that thought and the other thoughts that emerge until there is a sense that a core belief has been reached.

Double Standard

Patients are frequently inconsistent in the way they apply their judgments across persons. In some cases, they are much harsher with themselves than with others. The question, “What would you say to another person in the same situation?” can often elicit a double standard—a series of rules that apply to themselves and a different, more lenient set that apply to others.

Sometimes people with anger problems invert this process. They have a higher standard for others than they do for themselves. One patient who was in recovery spoke disparagingly of a friend who had violated one of the guidelines of Alcoholics Anonymous by beginning to date someone during the first 12 months of her recovery. When asked when she had started dating her own husband, she replied that it was 8 months after she began attending the self-help group.

Keeping a Daily Log

In their daily activities and experiences, patients can go into the world and keep a log in which they gather evidence that both supports and refutes their belief. This is the data-gathering aspect of the personal scientist model (Mahoney, 1974). They can also speak to trusted friends and family members about how they would see a specific situation. In this way, they can also work on collecting alternative perspectives.

Distinguishing Possibility from Probability

With the anxiety disorders, patients are often worried about negative events. For some, the Internet has become a way to have rapid access to even more information about the possibility of unpleasant or even dire consequences. Although in some cases patients may be worried about things that are not true, more commonly, they are worried about things that have a low possibility of occurring. For those suffering from anxiety, it is as if everything were equally likely to happen—a plane crash has the same probability of occurring as a car crash. This may be the way that they feel, and reality testing helps reorient the individual toward a more balanced view of life that not only helps him or her be less fearful, but also demonstrates that feeling something does not mean that it actually is true.

Examining the “Feared Fantasy”

Examining fears involves not only looking at the things that patients are most frightened of, but also creating plans for coping with the situation if it occurs. This serves to reduce anxiety and to increase the sense of self-efficacy.

All of these techniques are ways of changing thoughts. The next level of intervention is to challenge the maladaptive assumptions. The content of these typically involve the patients’ rules for living, their shoulds, musts, and if-then assumptions (Leahy & Holland, 2000).

Maladaptive Assumptions

Evaluating Patient’s Standards

The issue is where patients draw the line for themselves. A patient who, with no formal training had made cooking a hobby, felt that he was a terrible cook. He ranked the master chefs at 100, the average person at 50, and himself at 70. For him to be a good cook, he would have to be in the 90s.

Examining the Patient’s Value System

Some people are trying to be successful at everything. By looking at their values and making a priority for what is important to them, they can focus their energies more judiciously.

Distinguishing Progress from Perfection

This is a good example of moving away from the dichotomous thinking so often found in psychopathology. Because perfection is an unattainable goal, the therapist and patient can have a dialogue about the advantages of focusing on progress. Alcoholics Anonymous actually recognizes the potentially negative consequences of this and their members use the slogan, “Progress not perfection.”

Borrowing Someone Else’s Perspective

In this case, the patient would identify an individual that he or she believes functions well. They would then try to imagine how that person would approach a given situation or problem.

Core Schemas

When trying to change the core schemas, an intermixing of Gestalt or emotion-focused and cognitive techniques is usually best. As seen later, this combination is used in schema therapy (Young et al., 2003), typically including the techniques reviewed in the following sections.

Historical Identification of the Schema Sources

Identifying the source of a schema involves a historical review of the people and situations that encouraged or supported the development of a schema as well as those who opposed it.

Imagery and Emotions

Using imagery or emotion is another way to assess for schemas. When patients are upset about situations in their current life, they can be asked to close their eyes, to become aware of what they are feeling, and to allow a memory from the past that evokes the same emotion to rise to the surface. This memory is less likely to be influenced by the specifics of the current situation and more likely to be an accurate reflection of the theme that is underlying the disturbance.

Imagery Restructuring

Maladaptive schemas may be connected to particularly traumatic events and/or to living in sustained relationships filled with disturbed messages and/or behavior. Using imagery, the patient can confront those who were involved in the creation of the schema. In situations in which there was an actual trauma, the traumatic scene can be replayed so that the child can be defended and the perpetrator defeated (Arntz & Weertman, 1999; Smucker, Dancu, Foa, & Niederee, 1995; Young et al., 2003). In situations of emotional abuse, the imagery work may be one in which the persons responsible are confronted, the poisonous messages are identified, and the patient makes a clear decision to reject this and to live his or her life on a different basis (Elliott, 1995; Goulding & Goulding, 1997).

Letter Writing

Patients can also write letters to people who have hurt them. In them, they outline how they were hurt and how they are now planning to go forward in their lives. These letters are read in session but are not actually sent. The purpose is to express feelings that were not and could not have been expressed in the past and to challenge the hold that the resulting schemas have had on their life.

Schema Dialogues

With this approach, the core beliefs that are contained in the schema are delineated. A new, healthier schema is created by writing down statements that counter the dysfunctional ones. The patient would then do chair dialogues in which [he or she] would go back and forth, first making the case for the dysfunctional schema and then making the case for the new, adaptive one. Typically, this needs to be done repeatedly before the patient begins to make an emotional connection that is more than just words to the new schema.

Therapeutic Sequences

Cognitive therapy is generally a short-term therapy, and the clearer and more discrete the symptoms and the higher the level of motivation, the more rapidly the patient can be treated. Patients with multiple problems and difficulties can present a more difficult and longer course. However, a focused, systematic approach (Persons, 1989) can go a long way toward making psychotherapy an effective and efficient process.

The therapy begins with problem clarification. The patient and therapist do a thorough exploration of the patient’s current problems and difficulties and work to organize them into a hierarchy of importance and psychotherapeutic viability.

In the next step, which is part of a broader effort to socialize the patient into the cognitive model, the therapist strives to help the patient see the connection between cognitions and emotions. This can be done using examples from the patient’s life as well as from mood shifts that they are experiencing in the session (Young et al., 1993). In a video, Beck asks a patient about his thoughts and feelings on his way to the session as a way to make this connection (A. T. Beck, 1986). Another way to socialize a patient into the cognitive model is through bibliotherapy or the use of suggested readings. Burns’s (1980) Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy and Greenberger and Padesky’s (1995) Mind over Mood are both commonly recommended.

Therapists also strive to maintain a problem-focused stance. This includes emphasizing the scientific process and the importance of the patient codesigning and completing homework. (Homework is discussed later.)

Structuring a Session

In terms of the structure of an individual session, the patient and therapist set an agenda for the hour after briefly touching on the events of the preceding week. Because there may be more problems than can be addressed in one session, they make a priority list and choose one or two to work on.

Through the use of questions, the problem is explored and dissected to see if there are “early maladaptive schemas, misinterpretations, or unrealistic expectations” (Young et al., 1993, p. 248) at its core. This information is then conceptualized in a cognitive-behavioral manner and the “significant thoughts, schemas, images, or behaviors” become the focus of treatment. These are addressed using cognitive and behavioral techniques and through the use of a jointly created homework assignment.

As the session winds down, the therapist provides a synopsis of what has been explored and accomplished, and the patient is asked to write down a summary statement that they keep. The patient is also asked for feedback about the session and any concerns are clarified (Young et al., 1993).

Homework

Homework has long been a key feature of cognitive therapy, and it serves several functions. It not only is a way to collect information, assess the accuracy of the hypotheses, and modify the underlying schemas, but also it provides a way to apply what was learned in the session to the real world, thus enabling the patient to have an experiential, rather than a simply intellectual understanding of the issue (Garland & Scott, 2002; Young et al., 1993).

In a typical cognitive therapy session, homework is a central issue. This means that the projects that were assigned in the previous session, whether done or not done, need to be adequately explored. Sufficient time needs to be set aside in each session to design jointly the homework for the week. This discussion should include a clarification of the rationale, clear guidelines on what should be attempted, and problem solving around possible internal or external factors that could interfere with its successful completion (Garland & Scott, 2002).

The kind of homework projects assigned are likely to vary with the phase of treatment. As noted earlier, the initial stage of treatment is one centered on the assessment and clarification of the belief structure. Homework using the DTR is often an important activity at this time.

The next phase might involve two different kinds of work: (1) to go into the world to test a belief or a schema and (2) develop new ways of behaving in real-life settings.

Nothing is wasted in cognitive therapy because each encounter with the patient, especially those that are problematic, provides the therapist with the opportunity to understand better the patient’s beliefs and schemas (Bedrosian & Beck, 1980). This also means that homework is presented and viewed in a “no-lose” manner, and if the patient does not complete the homework assignment, a great deal can be learned from that as well (Garland & Scott, 2002). Last, research shows that patients who complete their homework assignments are more likely to get better—which should give added impetus to the goal of the therapist and patient collaborating to design successful homework projects (Garland & Scott, 2002).

Strategies and Specific Disorders

As was presented earlier, there is a wide range of interventions available to the cognitive-behavioral therapist, and he or she can design an intervention plan that is appropriate for the case. The techniques chosen are suited to the diagnostic categorization, the symptoms of the disorder, and the specific needs of the patient. For example, in the anxiety disorders, cognitive techniques are used to address perceptions of danger, whereas with depression, they address concerns about badness.

Cognitions and Pathology

Although not a fixed dichotomy, in some cases, cognitive therapy is focused on changing the beliefs that are at the core of the disorder; whereas in others, the intention is to change the attitude that the patient has toward an existing situation. Moorey (1996) has written about the cognitive therapy of real-life difficulties such as cancer. He maintains that these kinds of crises and challenges, although universally seen as difficult, also have personal meanings for the patients that are experiencing them. By adopting the same principles that are used with psychiatric disorders, patients can be helped to have improved moods and coping abilities. He challenges the “everyone would be depressed” argument, and in doing so expands the possibilities of cognitive therapy.

Medication

At the present time, there does not seem to be an overarching philosophy toward the use of medication among cognitive therapists (L. McGinn, personal communication, February 9, 2007). In some research protocols, medications are used first and for those who do not respond, cognitive therapy is then added on. In other studies, the psychotherapy is begun first and then medication is provided for those who need it (A. T. Beck, 2005). In studies using CBT with patients suffering from schizophrenia, they were typically also receiving medication (Rector & Beck, 2001). A. T. Beck (1985), in the past, made the argument that both psychotherapy and medicine were making changes in the structure of the brain so there was no need for there to be a conflict, per se.

However, there does not appear to be any significant research support for the idea that medications improve the quality of response in patients receiving cognitive therapy for depression, except in severe cases. In addition, patients may prefer to not take medications (A. T. Beck, 2005; Young, Rygh, Beck, & Weinberger, in press), and medications may be problematic in two ways related to relapse and confrontation.

The first problem would be the issue of relapse. According to the cognitive model, lasting change best occurs in the context of the alteration of core beliefs. To the degree that the person gets better and the core beliefs are not changed, the patient is at risk for a relapse. This does not mean that medication does not facilitate therapeutic change nor that an increased ability to function due to the freedom and relief provided by the medication does not lead to schema change in and of itself, but the long-term prognosis may be better if these deeper changes are made.

The second issue is that for some of the anxiety disorders, particularly social anxiety and panic disorder, the patient needs to confront the feared situation and experience some anxiety. If the patients are unable to go through this exposure process, they are less likely to profit from therapy. For those who are extremely anxious, it may be possible to titrate the medication to reduce but not eliminate their fear. In this way, they are not so overwhelmed that they cannot do the exposure work, but they are not so calm that they do not reap its benefits.

Although it may be common practice to combine medication and cognitive therapy, this may be based more on pragmatism or professional allegiances than on research findings (Young et al., in press). More work needs to be done to study the impact of CBT and psychotropic medication, alone and in combination. We hope that the larger treatment field will fully endorse the fact that, in many cases, cognitive therapy is the only treatment that is needed.

Curative Factors

At this stage of psychotherapy development, most theorists and researchers will emphasize the crucial importance of the therapeutic relationship or alliance in making change possible. Moving beyond this, A. T. Beck has stressed the factors that he believes are at the root of effective change.

The first is that there must be a comprehensive framework or rationale of treatment that makes sense to the patient, an overview that explains both the nature of the problem and a way to change it. The second is that during the treatment process, the patient engages with the problem (either in reality or fantasy) in a manner that includes significant levels of emotional arousal. Last, there must be some kind of reality testing or process in which problematic beliefs are tested in appropriate situations. Cognitive therapy, A. T. Beck feels, meets each of these requirements (A. T. Beck, 1987; A. T. Beck & Weishaar, 1989).

Gender Issues

Issues of gender and sexism have not been adequately addressed by any of the major psychotherapy movements (Daniels, 2007), and this may have occurred because the developers were unaware of some of the cultural assumptions that were underlying their work. In this regard, cognitive therapy in its traditional form has been seen by some as lacking a sense of cultural context (Ivey, D’Andrea, Ivey, & Simek-Morgan, 2007).

Although CBT needs to develop further to more fully capture the experiences of women that may underlie their suffering, aspects of CBT have been utilized successfully in a feminist framework. Going back to the 1970s and still continuing in various guises today is an emphasis on consciousness-raising (Prochaska & Norcross, 2007). Whether done in a group or individual format, this process involves working with women to help them first to become aware of the assumptions that rule their lives and then to understand that many of these stem from a culture that has traditionally held them to an inferior status. Their problems and difficulties are reframed as being the result of social inequalities, rather than due to personal weaknesses. The result is that they begin to develop new ways of seeing their world and themselves in that world. Assertiveness training can be used to help women clarify and gain their voice and act more successfully to get their needs met. Relaxation therapy and other forms of stress reduction can be used to help them cope with the givens of sexism and the additional stress that may occur when they make efforts to gain power. Last, psychotherapy can help them challenge socially conditioned problematic beliefs that may constitute a form of internal oppression (Hill & Ballou, 2005 in Ivey et al., 2007). The historical review that often takes place around the origin of schemas could now be undertaken with an eye to the experiences of being female in the larger patriarchal culture as well as to those based in family or peer relationships.

Multicultural Issues

Like gender, the issue of working psychotherapeutically with individuals, couples, families, and groups who are members of cultural traditions that differ from the White, American mainstream is going to become increasingly central to all psychotherapists in the years ahead (Iwamasa, 1996). Although this reality is currently being acknowledged, there is a great deal of work to be done to find out how to do it effectively and implement it broadly. An interesting moment, in this regard, occurred at the 1999 Conference of the American Counseling Association. There was a debate about REBT, irrational beliefs, and cultural background. Albert Ellis responded to these criticisms by proposing that he add a C (contextual/cultural) component to his therapy, making it REBCT (Ivey et al., 2007).

With a multicultural approach, the values of the individual and the experiences of oppression and disenfranchisement that sometimes accompany them are put at the center of the therapy, and the therapeutic relationship and techniques are adjusted to it. For example, an extremely talented African American female lawyer spoke in therapy about the limits that she faced in her corporate law firm. She simply did not believe that she would ever make partner—regardless of what she did. Because of this, she was making a decision to focus more on her life outside of the firm. Her perception of limitation was supported by a recent article in the New York Times pointing out that although increasing numbers of African American lawyers were being hired by the top law firms, few of them were actually being chosen to be partners (Liptak, November 29, 2006). In this case, an exploration of her decision not to seek a partnership needed to be informed with an acknowledgment that, while not impossible, her goal would be very difficult to attain.

Hays (1995) argued that there were several strengths in the cognitive therapy model that would fit well in this context. Cognitive therapy has traditionally been interested in the unique experience of the individual; taking a multicultural perspective would be one more way to better understand the patient so that the appropriate interventions could be designed and implemented.

Cognitive therapy also emphasizes learning and empowerment. In this regard, there is a belief in and a respect for the capacities of the individual, and this can help create a collaborative process. In addition, a focus on empowerment can be helpful with those who are dispossessed. Last, the centrality of conscious cognition and specific behaviors may be especially effective when English is not the primary language of the patient or when a translator is involved.

Adaptation to Specific Problem Areas

Cognitive-behavioral therapy has been adapted to treat a wide range of disorders, and specific manualized protocols have been developed for each of them. These include depression (A. T. Beck et al., 1979; Greenberg, 1997), panic disorder and agoraphobia (Clark, 1996; Craske & Barlow, 1993), generalized anxiety disorder (Costello & Borkovec, 1992), social phobia (Hope & Heimberg, 1993), specific phobia (Leahy & Holland, 2000), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Calhoun & Resick, 1993; Leahy & Holland, 2000), obsessive-compulsive disorder (Salkovskis, 1996), schizophrenia (Rector, 2004), drug and alcohol addiction (Marlatt & Donovan, 2005; Marlatt & Gordon, 1985), marital difficulties (Baucomb, Epstein, & LaTaillade, 2002), bulimia nervosa (Fairbairn, 1985), and anorexia nervosa (Garner & Bemis, 1985). As noted earlier, there have been a number of efforts to treat personality disorders using cognitive-behavioral therapy, and we now turn the focus to schema therapy (Young et al., 2003).

Schema Therapy

The work to develop schema therapy began in the early 1980s. At that time, Jeffrey Younga was working with Aaron Beck. He was particularly interested in those patients who did not respond fully to cognitive therapy or who would make gains only to relapse. He also found that when he treated patients in his private practice, he was not achieving the same results that had been found in research settings with a more carefully selected group of patients (Collard, 2004). Not uncommonly, these were cases in which the patient did not follow through on homework assignments, had difficulty identifying what was problematic, was not responsive to treatment, and/or kept relapsing (Young & Klosko, 1993).

The characteristics that began to emerge were that these were individuals whose schema structures were very rigid, and, consequently, the standard cognitive restructuring techniques were not having an impact on their worldviews. Many of these patients also reported histories of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, and they had a much higher frequency of personality disorders (Collard, 2004).

Young began to look at the themes that kept appearing in the work that he and others were doing with these patients. What emerged were a series of constructs about the self, others, and the future that were particularly detrimental to healthy functioning. Clinical practice and research eventually determined that there are 18 major early maladaptive schemas (Young et al., 2003; see Table 3.2). The belief is that these problematic world- and self-views develop when the core needs of the child are not met. These include the needs for security, autonomy, competence, identity, freedom of expression, spontaneity, play, realistic limits, and self-control (Young et al., 2003). These schemas may reflect the experiences that the patients had as children or adolescents, and they may also reflect the survival mechanisms that the children used to adapt to difficult situations. They are emotionally valent and are treated as accurate, regardless of how distorted or problematic they may be at the present time.

Table 3.2 Early Maladaptive Schemas

Source: Adapted from Bricker and Young, 2004.

| Disconnection and Rejection |

| Abandonment: The expectation that you will soon lose anyone with whom you form an emotional attachment. |

| Mistrust/Abuse: The expectation that others will intentionally take advantage of you in some way. People with this schema expect others to hurt them, cheat them, or put them down. |

| Emotional deprivation: The belief that your primary emotional needs will never be met by others. |

| Defectiveness/Shame: The belief that you are internally flawed, and that if others get close, they will realize this and withdraw from the relationship. |

| Social isolation/Alienation: The belief that you are isolated from the world, different from other people, and/or not part of any community. |

| Impaired Autonomy and Performance |

| Dependence/Incompetence: The belief that you are not capable of handling day-to-day responsibilities competently and independently. |

| Vulnerability to harm and illness: The belief that you are always on the verge of experiencing a major catastrophe (e.g., financial, natural, medical, criminal). |

| Enmeshment/Undeveloped self: A pattern in which you experience too much emotional involvement with others—usually parents or romantic partners. It may also include the feeling that you have too little individual identity or inner direction. |

| Failure: The belief that you are incapable of performing as well as your peers in areas such as career, school, or sports. |

| Impaired Limits |

| Entitlement/Grandiosity: The belief that you should be able to do, say, or have whatever you want immediately, regardless or whether that hurts others or seems reasonable to them. |

| Insufficient self-control/Self-discipline: The inability to tolerate any frustration in reaching your goals, as well as an inability to restrain the expression of your impulses or feelings. |

| Other Directedness |

| Subjugation: The belief that you must submit to the control of others to avoid negative consequences. |

| Self-sacrifice: The excessive sacrifice of your own needs to help others. |

| Approval seeking/Recognition seeking: The placing of too much emphasis on gaining the approval and recognition of others at the expense of your own genuine needs and sense of self. |

| Overvigilance and Inhibition |

| Negativity/Pessimism: A pervasive pattern of focusing on the negative aspects of life while minimizing the positive aspects. |

| Emotional inhibition: The belief that you must suppress spontaneous emotions and impulses, especially anger. |

| Unrelenting standards/Hypercriticalness: The belief that whatever you do is not good enough, that you must always strive harder. |

| Punitiveness: The belief that people deserve to be harshly punished for making mistakes. People with this schema are critical and unforgiving of both themselves and others. |

One issue that Young observed was that these patients were often using problematic behavioral or coping styles to address or avoid the issues contained in their schemas. Coping styles that were based on overcompensation or avoidance meant that it might be necessary to try to elucidate the schema structures indirectly. In this regard, Young had found a way to reintegrate defensive processes—which is of note because defenses were one of the concepts that A. T. Beck had eliminated in his initial formulation of cognitive therapy (Bedrosian & Beck, 1980).

A second area of innovation was the idea of multiplicity or multiple aspects of the self. Dividing the individual into parts or modes would at first prove to be an invaluable way of understanding and working with patients with more severe personality disorders; it would eventually prove to be an effective way to work with a wide array of difficulties.

The third area of innovation was his expansive use of the therapeutic relationship as a healing vehicle. Not only was the relationship a cornerstone of treatment, the therapist was now guided to adjust his supportive and connective behaviors in response to the schema profile of the patient. This is called limited reparenting and it is discussed later.

Coping Modes

Originally called coping styles (Young & Klosko, 1993), coping modes represent three attempted solutions for adapting to the painful schemas in the patient. In traditional cognitive therapy, there is a logical progression from the automatic thoughts through the underlying assumptions to the schemas. This becomes more complicated with personality disorders. Essentially, the individual has three ways of coping with the schema: (1) surrender, (2) avoidance, and (3) overcompensation. Surrender is the most straightforward. Here the patients live their lives as if the schema were true—they frequently seem to be drawn to experiences that confirm it. A man with an emotional deprivation schema marries a woman who is cold and unloving. A woman with a combination of defectiveness and failure schemas leads a life of underachievement.

With an avoidant coping mode, a patient seeks to avoid situations that trigger the schema. With a defectiveness schema, a patient may take a more guarded approach to social interaction. The patient may avoid revealing his or her real opinions or feelings about things. Those with a vulnerability schema may avoid going to places in which there is any hint of danger.

With overcompensation, the patient goes to the polarity of the schema, and, by definition, goes too far. For those with as ubjugation schema or a history of being oppressed by parental figures, the solution may be to rebel against all authority, which may damage their ability to function in educational and work settings. In turn, those who have schemas of emotional deprivation may become extremely demanding of attention and affection from others, while those who have mistrust/abuse schemas may become aggressive or abusive toward others in the hopes that this may serve as a kind of preemptive strike against being mistreated by them (Young et al., 2003). As is probably clear from these descriptions, all three coping styles have the potential to lead to problematic life and interpersonal consequences.

Schema therapy recognizes that, at their core, these patients have needs that are to be respected and that the goal of therapy is to help them find effective ways to get them met in the real world. However, because of the complexity of the patients that were encountered, it was necessary to develop two approaches to treatment: (1) the original schema model and (2) the schema mode model.

Original Schema Approach

The original schema-focused approach is most commonly utilized with less severe characterological issues. It emphasizes the importance of education, assessment, and schema change. An initial goal is to make a connection between the presenting problem and the individual’s core beliefs. To this end, it is necessary to approach the assessment process using a variety of methods. Perhaps the first place to start is to do a historical review of the presenting problem or symptoms to get a sense of whether schemas are involved, what they might be, and what might activate them.

Second, moving beyond a clinical evaluation, there are a number of questionnaires that are used to more formally evaluate these dynamics. The Young Schema Questionnaire (YSQ; Young, 2001) is typically given. This is an extensive questionnaire that has items covering all 18 schemas. After it is scored, the patient and therapist engage in a further exploration of the meaning and history behind the schemas that were highly endorsed. This is the most straightforward method of assessment, and this measure has been validated across cultures.

Because schemas often develop out of problematic childhood experiences, patients are given the Young Parenting Inventory (Young, 1994). This asks about parental behaviors that are thought to contribute to the development of maladaptive beliefs, and results from this assessment can be integrated with those from the YSQ.

Third, experiential techniques are also used to help with this kind of diagnosis. As described earlier, patients can be asked to close their ideas and bring in images of problematic memories from childhood. Typically, the patient is requested to visualize troubling memories concerning parents, siblings, and peers. The therapist and the patient work together to clarify the needs that were not being met in those situations and to assess for the presence of abuse and trauma.

Last, the clinician can also look to the therapeutic relationship and the experience that he or she is having with the patient. This is another valuable source of information about the schemas that may be operating in any given patient. After the assessment phase comes the change phase. Although the presenting problems are significant, they are seen as a manifestation of the underlying schemas. The dysfunctional schemas are challenged and changed by (a) using the therapeutic relationship, (b) incorporating cognitive techniques, (c) integrating experiential approaches, and (d) working with patients to change their self-defeating behavior patterns.

Limited Reparenting

This is a relational approach that takes the therapist a step beyond the crucial goal of building a therapeutic alliance. The schema model is based on the belief that the maladaptive schemas developed because core needs were not met. In limited reparenting, schema therapists attempt to create a therapeutic relationship that is able to provide a “corrective emotional experience” (Alexander & French, 1946); that is, they work to meet the unmet emotional needs of the patient.

For example, patients with an emotional deprivation schema have often not received enough engagement, connection, or guidance from their parents. When a patient with this schema asks for advice, the therapist usually provides it because this kind of nurturing is exactly what the patient needed but did not get. Patients with a mistrust/abuse schema have often had a history of painful or traumatic relationships. To help correct for this, the therapist takes a stance of transparency, of being “completely trustworthy, honest, and genuine with the patient” (Young et al., 2003, p. 203). The therapist asks the patient about his or her feelings of trust throughout the therapy process, looks for watchfulness and guardedness, ask about negative feelings, and does any trauma work slowly so that the patient feels safe and connected.

The second way that the relationship foments change is through empathic confrontation (Young et al., 2003). Schemas fight to maintain their existence. In empathic confrontation, the therapist maintains his or her connection with the patient, acknowledges the difficulty of change, but nonetheless pushes the patient to challenge the schema and to do the things he or she finds difficult or anxiety producing.

Using Cognitive Approaches in Schema Therapy

The goal here is to test and challenge the veracity of the schema. The content of the schema is clarified and evidence is gathered from the past and the present that both supports and refutes the schema. The negative consequences of the schema are pointed out, evidence that supports the schema is reframed in different ways, and solutions are generated to help the patient cope more effectively in the present. This is similar to testing the validity of automatic thoughts, except that with schemas, the patient has a lifetime of evidence to be tested for each schema.

One of the essential goals of schema therapy is the development of the Healthy Adult mode or a flexible, positive, centered, and creative aspect of self. In a mix of cognitive and experiential techniques, a two-chair dialogue (Kellogg, 2004; Young et al., 2003) can be created between the part of the person that embodies the schema and the healthy part that refutes its dysfunctional beliefs. Because this healthy voice may be unfamiliar to the patient, a script can be jointly created. At first, the patient affirms the schema side while the therapist affirms the healthy one, and then this is reversed. Eventually, the patient is encouraged to engage in a two-chair dialogue in which they go back and forth affirming the schema in one chair and refuting it in the other. This needs to be done repeatedly so that the patient can go from knowing it intellectually to fully integrating it into his or her worldview.

Patients can also develop schema flashcards that they can read several times a day to help continue this kind of integration. They can also keep a schema diary in which they identify the triggers that activated the schema; clarify how the schema manifested itself in terms of their thoughts, feelings, and behavior; understand the degree to which the schema was an inaccurate interpretation of events; and list the healthy behaviors that they did or could have engaged in.

Because many schemas involve interpersonal relationships, they can be tested in the therapeutic setting. Good opportunities for this can take place when the patient misinterprets something the therapist said or shows emotional distress; nonverbal cues can be another source of important information. The therapist and patient can work to clarify the cognitions and emotions involved and connect them to the specific schemas. Reality testing can take place as well in that there may be some justification for the patient’s feeling beyond their distortions and overreactions.

Experiential Techniques in Schema Therapy

Imagery is the central experiential technique, and it is used in four ways. First, at the beginning of therapy, imagery can be used to help get a schema diagnosis. Patients can be asked to bring up disturbing memories from their childhood, and the themes that emerge can be used to clarify the core schemas.

Second, during the change process, patients can be asked to call up these same or other problematic memories or images. They can then have dialogues with the hurtful figures and have an opportunity to say, often angrily, what could not have been said in the past.

The third way of using imagery is as a form of reparenting. Here, the patient calls up an image of him- or herself as a child and the therapist and the adult patient, respectively, have an empathic and affirming dialogue with the child.

In cases where there has been abuse, the traumatic memory can be brought up and the scenario replayed. The patient and therapist can enter the scene and stop the abuse and/or the inner child figure can be given a wall or barrier to protect him or herself. In this way, the patient learns to self-parent.

Behavioral Pattern-Breaking